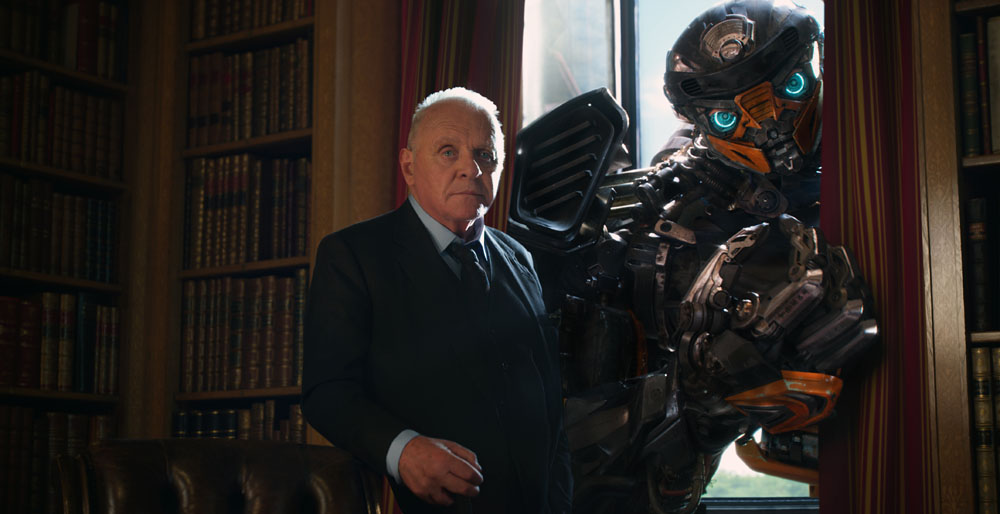

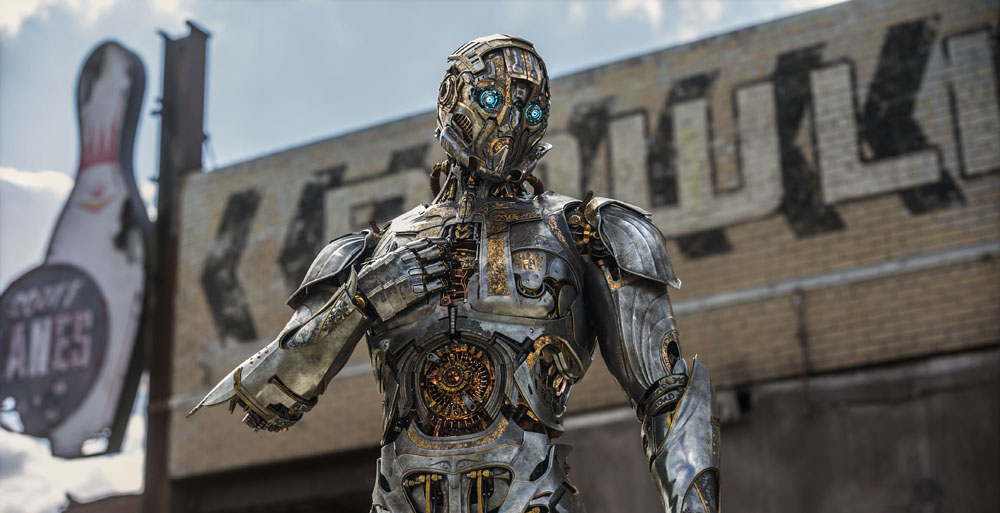

Art of the Cut takes a step into the epic – not just with the film we’re discussing – but because to cover the editing of Michael Bay’s Transformers: The Last Knight, we spoke to four editors in three separate interviews. The exciting thing for readers of Art of the Cut is that when you get six top editors on a single picture, they all learn from each other in ways that are impossible without working on the same footage and with the same director. Those important lessons are at the core of this Art of the Cut.

The six editors listed as “editors” are Roger Barton (Pirates of the Caribbean: Dead Men Tell No Tales), Adam Gerstel (Star Trek Into Darkness, Previs editor), Debra Neil-Fisher (The Hangover), John Refoua (Olympus Has Fallen) , Mark Sanger (Gravity), and Calvin Wimmer (13 Hours). We had the opportunity to speak to all of them except Barton and Wimmer.

HULLFISH: What are the challenges of working with so many editors or are there only advantages?

SANGER: For me – and I’m not just saying this because they were all really good people to work with – there were no real challenges individually. The challenges as a group were that Michael would often have us working on sections that would overlap. And we would have to communicate all the time to ensure that we weren’t wasting time doubling up. We had to ensure that we were always aware of what the other editors were working on (and what they had already done) because often we found that when I had been cutting one version of a scene three weeks beforehand and so when Adam would go in and be looking at that same scene three weeks later, I would check what he had done and then go back to him and say, “Hey, you know, when I was going through your version, I found this moment that was of no use to me in my version, but seeing what you’ve done, take a look at it.”

We were collaborating on scenes even when one of use was assigned to a different scene. We would peek our head around the corner and say, “Hey, take a look at this shot.” It was really challenging just to ensure that we never trod on each other’s shoes. The benefits are endless because due to our schedule restrictions you could never make a movie of this size with this volume of material without several collaborative editors all working at the same time. It’s an impossibility.

REFOUA: None of us, except Roger, had worked on a movie with so many other editors before, so it took a while for us to figure out how we were going to do this and what does Michael (director, Michael Bay) want? Eventually, you settle into a rhythm and you really have to put your ego on hold because a scene that you work on — Michael, likes to move scenes around from editor to editor. He just wants editors to try different things and eventually he’ll say, “I like that one from this guy…This part from that guy.” So that took a little getting used to.

GERSTEL: What was great is after you put a scene together, you get to see somebody else cut the same scene and it really brings to light a different way that you hadn’t thought about. And so the next time you go to cut a scene in the film that may be similar you’re already now thinking of two different way of doing it. It really expanded your view because you’ve seen so many versions of the scenes while also having an intimate knowledge of what footage was there to put them together. You knew what challenges you had when cutting them and you see how somebody else dealt with those same challenges. It’s quite a learning experience.

NEIL-FISHER: It was fun actually. It was great to see How each of us approached the material differently. Learning from each other was really awesome. Especially for me. I don’t work as often on action pictures so it was really fun to see everybody’s versions on those scenes. I was fascinated by how many versions you can do of an action scene. How exciting and interesting each one was. And then moving on from here I take that with me and use it on the next thing I’m working on.

GERSTEL: Exactly. And this was a complicated story. There’s a lot in there. It has a lot of depth, a lot of layers. And so there was constant conversation about how best to structure it. Michael loved to intercut and he also is not tied to the script so everything is up for grabs and we were always trying new ideas. We would sit, all of us in the room and just talk about what was the best way to put a scene together or put a sequence together. So it wasn’t just always one person taking a stab and then another person taking a stab. There were many times when we were all just discussing it together. Almost like a writers room for editors.

HULLFISH: Every couple of years I go to this thing called Editors Retreat, and one of the great things about that is just getting a chance to spend time with colleagues, talking about the art and techniques and struggles and geeking about technology with someone else who cares.

HULLFISH: Every couple of years I go to this thing called Editors Retreat, and one of the great things about that is just getting a chance to spend time with colleagues, talking about the art and techniques and struggles and geeking about technology with someone else who cares.

REFOUA: There’s something about editors. We’re all at a certain wavelength. I like editors. They’re my favorite people actually. On Transformers we would all talk to each other a lot. And when Michael handed off your scene to someone else, it was interesting to see what that editor would do with the same material. I respected every one of the other editors. They’re all accomplished. Sometimes the scene would pass through several other editors and then come back to you. I was always very curious to get into the details of what other editors had done and I really enjoyed being surprised with cuts they had made. There was a lot of camaraderie between all of us.

GERSTEL: It was definitely was a collaborative process. We really worked well together.

HULLFISH: At one point there were seven editors on the show. Tell me a little bit about how it worked. How were scenes divvied up?

GERSTEL: We would get all the dailies in and Michael would talk about the dailies with us and about what he saw in a scene. The way that Michael works is not traditional: “It was not – You take this scene. You take this scene. That’s your scene. That’s mine. Never shall the two meet.” When we got dailies it was “who wanted to take what” unless Michael had a specific request for someone to cut something, which would happen, but for the most part, we would divvy up the dailies based on what we were interested in cutting that day. Michael would give notes and say, “OK I like this version. OK, John, now you take a stab at it. OK, Mark, now you take a stab at it. Deb, you take a stab at it.” Everybody cut everything. So really, by the end of it, we had all cut every scene. There had been a version of every scene that every editor cut.

NEIL-FISHER: And it leads you to be quite inventive because maybe you would have approached it the same way the other person did, but now you were challenged to come up with a new version. It definitely made for an interesting challenge.

HULLFISH: So even though you thought, “Yeah, that’s how I would cut it. It’s perfect,” you couldn’t just say, “I’m going to leave it.” Right?

HULLFISH: So even though you thought, “Yeah, that’s how I would cut it. It’s perfect,” you couldn’t just say, “I’m going to leave it.” Right?

GERSTEL: Michael shoots so much, so there’s a wealth of footage to use. And for every scene that he shot there were five scenes that could be cut from it. So it definitely took a team to put this footage together. He shot three million feet of film on this one. Just going through that amount of footage – no one person can do it and come up with the best version. You really need a collaborative effort.

HULLFISH: Were there advantages to just seeing the way other people approached the same material? Very rarely do editors get a chance to see what somebody else would do with the same material.

SANGER: Yeah I couldn’t agree more. The greatest thing about the group that we had is that there were no egos. When you have that volume of material there are hundreds of different ways of putting the movie together. All we were concerned with was getting Michael’s vision onto the big screen, and that meant looking at each other’s work.

What I find even most fascinating was seeing how other editors work. John Refoua would always be very fascinated by my slow and archaic way of working and was always telling me, Why don’t you do it THIS way?” and would show me some hotkey that would get me through a process that I’ve been doing for 16 years, but he’d show me something that would take half the time.

Another gratifying aspect would be sitting down with these experienced editors and seeing them make the same habitual mistakes with their processes that you make and getting some relief from the fact that it’s not just you. The daily craft technical process: I found that quite useful watching how the other guys work.

HULLFISH: Talk to me a little bit about your approach. When you’ve got that much dailies for a specific scene did you have to approach it differently than maybe a more standard coverage?

SANGER: I like to do it organically depending upon the style of the director. All directors shoot differently so I actively avoid setting myself a particular way of working. That’s part of the fun of going into a new project with a new director: the way they shoot determines how I will assemble. But there is one key area that I won’t change and that’s how I get my assistants to prep the material only up to a certain level. Then beyond that, I will prep it myself because that’s how I learn the dailies.

The late and very great Jim Clark always used to mark up his own scripts, rather than use the script supervisor’s version. He would watch the dailies and mark up his own script as he learned them each day. Many of the old school British editors did things that same way. I was only their apprentice at the time but I’m proud to have learned from their wisdom and so what I do is my own version of that.

Some directors will shoot very quick takes while others leave the camera running for fifteen minutes at a time. I will adapt how I break down my dailies depending on how the shoot went.

With Michael Bay, you might get 10 hours of dailies for a single scene, and when that comes in you think, “How on earth am I going to get him an assembly by the end of the day?” I decided that 95 percent of my day would be spent assessing and breaking down the dailies. Then, as I was doing it I was developing a mental structure of how I was going to put that scene together. I work fast and make notes as you go. And then at the very last minute, I cut the scene and got it uploaded to him for wrap. You physically can’t go through 10 hours of material and then spent five hours editing. But you can go through 10 hours of material methodically and understand all the dailies and then put together a version at the end of the day that is solid.

That’s just what I did, the other editors have their own processes. But we all adapted to Michael’s process and combined it with our own and all were based on necessity due to the volume of material that we receive each day.

I create an old-fashioned KEM roll of all of the dailies for a scene then what I’ll do is I’ll then go on and mark up — particularly on a movie like this when there are so many different variations of the lines — I will go in and mark up the same moment even though they may say different lines — I’ll mark up the same moment with the same coloured marker for instance within the KEM roll and then what that means is you can then go through and see every different delivery and performance for any given version of that moment. Once I mark all those up I then sort my markers in my marker bin by color and I know that all the white ones have that moment I’m looking for I just click click click and I see every different iteration of that moment.

HULLFISH: I love it! I do something very similar but it takes me up longer so I might have to adapt your methodology!

SANGER: It takes a while to prep.

HULLFISH: My methodology is to take the KEM roll and then break the edits up into those same sections, but I’ll actually re-edit them in order so all of the set-ups for the first 7-8 seconds of a scene then the second 7-8 seconds so that you can play it as a sequence. So you take the KEM roll and use markers so you can jump from marker to marker to marker.

SANGER: Basically it means that you can leave your KEM roll intact. You can be virtually jumping to those moments throughout the same roll. If you’ve got a scene with three takes, it’s not worth doing because you can just go to the bin and open the takes you want. But if you’ve got multiple variations or if you are looking for specific moments. For instance, on Gravity, all those breaths that you hear are selected and edited together. Sometimes it was Sandra’s performance from beginning to end, sometimes if we needed to change the structure of the scene, then we’d need to edit Sandra’s performance and while we always honored her original performance, if we were making a change to the scene that meant that we would be trying something new, then I would need to be able to go in and access individual breaths. And those are all marked up. That gives you a lot more flexibility.

HULLFISH: I love that technique. I might have to adopt that. You really have to set your ego aside a little bit when you’re working with that many editors. Plus, Michael is just randomly taking “your” scene and giving it to another editor… that would be hard, I’d think.

SANGER: No, I don’t think it is. For me, that was freeing because normally as an editor you have the whole movie on your shoulders, whereas with Michael there is one clear leader on the film who is managing everything so when you sign on you know that editorially you’re going to be bouncing ideas back and forth between everybody else. And for me, we were sharing a burden. It’s a huge epic movie and to be able to share that burden between a bunch of like-minded individuals was a pleasure. The trick is that you know going in that’s what it’s going to be like. I think if you had an ego going in and you turned up and worked with a bunch of guys it just wouldn’t work because it was a well-oiled machine.

REFOUA: Sometimes I have selects and sometimes I don’t. Michael does his own selects and sends them to us but he says, “You are not restricted to these.” You get a good idea of what he wants in a scene by those selects. Michael shoots a lot of footage and a lot of really cool shots. There are not one or two shots that I think, “I have got to use these.” There are tens of cool shots for each scene. The dailies themselves are just gorgeous. Every shot! When I´m watching the dailies it´s a constant: “Wow this is a great shot! That’s a great shot!” Basically, my approach is to just dive in and go down a whole bunch of roads and then back up and do another version and another version and another version. Eventually, I get to something I want to show him. I really like to sleep on a scene though. Sometimes on this movie, I had to do it quickly. Usually, I like to go home and look at the scene the next day.

HULLFISH: Me too.

REFOUA: Michael shoots everything live. All the explosions are live. All the smoke is live and the human stunts are live. What we have is a bunch of plates with explosions, smoke, and stunts in them. Our main challenge, in action scenes, was trying to figure out: what’s supposed to happen here? We would talk amongst the editors and say, “I think this is supposed to happen here. And I think this shot’s for that. And a lot of times, Michael would say, “That shot isn’t for that spot!” or he’d say, “That’s cool! I can use this. Yeah, this is a good place for this shot.”

NEIL-FISHER: I definitely went through each scene looking from a specific point of view. If I was starting the scene fresh, I would look through the film and pulled selects of what I thought were the pieces that would work for me. I went through the dailies and found pieces that were going to aid my version of that scene.

HULLFISH: John mentioned that Michael will create his own selects reels. Was it weird using somebody else’s selects?

GERSTEL: No not at all. They were just suggestions from him. You didn’t have to take it as final. It was just, “Here’s what Michael pulled as his options.” Often, they were the same thing we would have pulled or a slightly different version. And sometimes we even shared each other’s selects.

SANGER: The selects reels were great at giving you some idea as to what’s in his head. The material was always very usable and often varied in style, tone, and performance. As an editor that can allow for infinite possibilities from the material. So Michael goes through and he makes the modern day equivalent of a process I truly miss – the lunchtime dailies screening, where the editor would sit next to the director, watch dailies and hear just what he or she was thinking. Michael doesn’t have time to sit down and go through things in depth because his schedule is so frenetic, but he knows his material precisely from the shoot and skims through, supplying his favorite moments.

He has an amazing database-like brain. He knows every shot in the movie based on which day he shot it. After you’ve assembled it you’ll have a preliminary conversation about where to take it from there. But it’s imperative you get that select reel before you start the scene because, without it, you would be lost at sea, you could be creating an infinite number of different movies due to the sheer volume of usable material.

HULLFISH: Some editors like to watch dailies backward to forward. I would think that with Michael Bay you need to be watching from beginning to end because you’re watching the scene evolve.

SANGER: Absolutely right. Well observed. The scene is often improvised. And so you need to watch the day to understand how Michael’s thoughts evolve across its course because take one is often very different from take five. What’s happening is everybody is warming up: the camera guys, Michael, the actors… and there’s a momentum that is achieved by take five, and you know that invariably he’s got to where he wants to be by that take. But that doesn’t mean to say that he won’t want to use moments from take three. Michael isn’t building from one to ten and then sticking with how he found the scene be at 10. What you’ll find is that he’s going on a journey with every scene and he gets to a point where he feels between one and ten he’s got everything that he wants. Many directors out there, you know that you can use the last of each of the set ups and that would be their favorite. With Michael, it will be anything at all across all takes of the scene. But you have to understand how his brain process worked.

HULLFISH: Michael’s got a very specific style. Everyone recognizes him as a very distinctive director. Does that make it difficult or interesting or present challenges to an editor when you’re presented with this amazing Michael Bay shot that has to be put in this specific spot?

REFOUA: He likes his shots and he fights for them and he wants them in and sometimes we have to rearrange a scene just to get that shot in so that it makes sense. And Michael does have a style.

GERSTEL: Every shot is like that for sure. And that’s the challenge: there’s so much good material. You have to pace it. You can’t make every shot the big Michael Bay shot. So you have to pick which one works the best and will service the scene and story. It’s a challenge of too much good stuff.

SANGER: On any other movie, you’d know, “Oh, that’s the key shot in the scene.” But on a Michael Bay movie, it’s just like any other shot. And as you start to watch the rest of the shots in the dailies, you start to understand what’s in his head. When you then see the combination of his other selects you then get a better idea of what the scene needs to be and as John says, every single one of those shots will in itself be a little mini masterpiece.

NEIL-FISHER: And he does so many of his effects “practical” there’s a lot of explosions that are practical, car flips and etc that are done on set and then you’re adding all the robots in later. He shoots a lot of great angles of these practical effects and you have to figure out what will be the best plate for the robots. What would look coolest when ILM adds the robots in. It makes for really complicated choices.

HULLFISH: Mark, does Michael’s distinct style restrict you or free you as an editor?

SANGER: Freed by it! I’ve never seen dailies like it. Because of Michael’s back catalog, you immediately have a good sense of the moments he’ll want to use there. You know specifically that he wouldn’t necessarily go with a moment that his other contemporaries might choose. You get to the point where you think, “I know that Michael will want that moment. Because at that moment that character’s turning around and the light is hitting his face at THIS point, and I know that I can use that specifically at this moment. There is a shorthand that we all developed because Michael’s style is a known quantity. And that really does help. That gives you that broad foundation to your initial cut. Knowing Michael’s style and having the privilege of being able to emulate it on your first cut and then collaborate with him on your second and third cut is a joy.

HULLFISH: I figured that with the budget of the movie and with Michael Bay there would be a huge amount of footage. What is the solution to that? How do you deal with that much footage?

REFOUA: Michael likes to see a scene cut and then he’ll react. He shoots a lot even for the visual effects sequences. On this movie I learned, even more than on any other movie before, to just put my ego away.

GERSTEL: I’ve never seen more cameras on a shoot. We had something like twenty-six camera bodies. There were setups where there were several cameras rolling. They were all different and you’d really have to just go through it especially on the effects-heavy material. You wouldn’t get many takes, but they were really, really well covered.

HULLFISH: And did you guys do any multi grouping or grouping of cameras in multi-cam?

GERSTEL: We really didn’t and some of the reason is that not all of the cameras are rolling at the same time.

HULLFISH: People prepare their bins sometimes in special ways where they’ll put a multi-group in and then put the two cameras that form the multi-group above it.

GERSTEL: Mickey Mouse ears.

HULLFISH: So that brings me to another question. You had to have a large number of editors using the same bins. So how did that work out? How did you guys come to a quorum on how bins were going to be arranged?

NEIL-FISHER: I was in a completely different building also. So even though we were sharing the same media we had to figure out ways to keep a master cut and do our own cuts and integrate them every day. So it was quite an elaborate process.

GERSTEL: We were all very adaptable too. I kind of mold my process to whatever situation I’m in. So we all came up with the version of the bin that worked for everyone. There was no one who said, “I have to have all of my bins in thumbnail view with each row organized with all the takes in a column.” It wasn’t like that. Whatever was the most agreeable to everyone we just all worked with it.

SANGER: The scene bins were all shared but we had our own folder where you would go to the scene bin and take what you need and you go in your own folder and work privately with your own particular method. We all shared the same scene bins but for example, John would say to me, “There’s a really cool combination of shots of a scene that I was working on, and he would talk me through where it was in his folder. And basically, that folder would be what the Avid Project folder would be like on a John Refoua movie. And so there would be little sequence and you grab that from there and drag it across into your folder. So yes we’re all sharing the same dailies but we would work in our own areas and then supply our cut material back into the common area.

HULLFISH: And with so many editors working on the same scenes, did you have to come up with a common methodology for bin structure or how bins were laid out or did everybody do it differently? How did that work?

REFOUA: Michael likes to watch his dailies and there are a lot of bins set up for him and then for us. Since everybody likes their bins different, they were organized in a more generic way that anybody could open up and see what was going on.

HULLFISH: What was the methodology? How did you have the bins laid out?

REFOUA: We had an assistant go through, Eric Brodour, and that was his responsibility to get all of the scene bins and organize them by the script. Then he would put a little title card in there and the name of the title card would be the action that’s happening in the scene. And all pertinent clips would fit under that. That’s the way he did it and it seemed to make sense. Everybody was the least offended by it.

HULLFISH: So by title card, did he import a little JPEG that just said those words?

REFOUA: No. He’d just make a title card with the title tool in the Avid. It’s just black and you name it whatever it is that you want to be the name of the clip. Sometimes he would use a lot of dashes to clearly mark the separation.

HULLFISH: I have done interviews with multiple people — I know the whole Star Trek team — and they would actually import JPEGs with gigantic words so that when you’re looking at Frame view you could read the organizational material. When you were re-cutting a scene that had already been cut by another editor, did you start from scratch or did you try to save some of it or not look at the previous edit?

REFOUA: We all had to deal with cutting each others’ scenes. I do the same thing on my own scenes. A month later you say, “Hey, is there a better way to do this?”.

HULLFISH: It makes sense how you worked on individual scenes, but how did the editorial work when you got to the larger structural ideas of the overall movie?

REFOUA: Gradually the movie, as you put it together, it divides itself into sections. So Michael would say, “I want so and so to make a pass on this section. And I want so and so to try and shorten it and I want so and so to work on this thing that they do or I want somebody to check the jokes and make sure that we have the best jokes.” On Transformers, the editors became a team. We didn’t function as much as individuals but really the teamwork takes over. I had never been in that kind of situation to that extent, so that was cool and sometimes Michael would want three different versions of the same scene.

SANGER: He’ll look at scenes individually for a long time and then he might look at scenes assembled with a couple other scenes around them. But then we’ll start looking at things in reels. Instead of looking at those scenes within the reels for three or four weeks or four or five months in advance there’ll come a point where he’s happy with individual scenes then you’ll watch them in reels and when he’s happy with the reels, then you watch them in the movie. And so you kind of go in these much larger steps than many directors who would work on a scene by scene basis and then a reel by reel basis MUCH earlier on in the process. Michael works on a scene by scene basis for much longer and then makes these big leaps where we’re often watching the whole movie maybe on a Monday, Wednesday, and Friday. The changes that are going on within those five days are huge because with five editors you can get quite a lot happening in that amount of time. But it’s piece-meal for much longer at the beginning.

HULLFISH: That’s got the potential to just be a political nightmare but I’m glad that it worked out for you guys.

REFOUA: Really you have to put the politics away because you’re making a Michael Bay movie. You’re not making a John Refoua movie.

HULLFISH: That’s the quote of the day right there.

HULLFISH: That’s cool. That’s awesome. One of the things that Debbie kind of alluded to was kind of having specialties, like Mark Sanger, came from a background in VFX. He was a VFX editor before he cut Gravity. Debbie came from all this place of doing a bunch of comedies. Did you find that people were specializing or asked to be specialists in certain areas?

NEIL-FISHER: Since I hadn’t worked with Michael prior to this, he saw what was on my resume and that was my introduction to him. So I understand why he sort of wanted to see what my take would be on the comedy scenes first. But eventually, once you get to know him we were all working on everything.

GERSTEL: I think you’re exactly right. Likewise, I started as a VFX editor and a lot of times I would be dealing with VFX-heavy sequences. But like Deb said, as soon as you get to know Michael more and there are more scenes to cut, we all had to jump in and all cut everything. So everyone mixed it up. I feel like each one of us had cut the entire movie and it became a real patchwork of all of our versions.

NEIL-FISHER: Versions of editing, but also versions of our thoughts. We spent a lot of time working on the story, honing the story, and making it make sense with Michael. He trusted all of us. He would have long discussions about what was working, what wasn’t and what we needed to work on story-wise, what we needed to work on pace-wise. It was a really collaborative effort and he was very interested in all of our opinions and what we all had to contribute.

SANGER: Michael had never worked with any of us before. There was a period at the beginning where each of us was brought on to handle a particular aspect of what he had planned in his head. And at that point, he was able to quickly see where our abilities lay. It was not compartmentalized in any way. Sometimes there were scenes where Michael was looking for somebody particular. There were certain reasons he picked each of us individually and initially we would be handed each of those moments and then over the course of the show everybody had a dip into every different scene.

HULLFISH: Before your Best Editing Oscar win for Gravity, your background was as both an assistant editor and as a VFX editor. Did your time as a VFX editor help?

SANGER: If you look at my early resumé I jump from first assistant editor to VFX editor and then occasionally I’d do both simultaneously. This was out of an urge to work with different directors and a necessity to pay the bills rather than any particular passion for VFX.

This background knowledge does help from the point of view of understanding how you are limiting or benefiting the VFX supervisor with your editorial decisions. For instance, there’s a scene in T5 where a character gets ejected out of a car as it transforms into an autobot. I cut it together one way and showed it to Michael and he said, “That’s not the way I directed it to work, but I really like it.” So I needed to make sure I checked in with Scott Farrar at ILM because if a director likes a scene cut one way but the dailies don’t accommodate for that to work during the VFX work, then as an editor you’d be responsible for creating a VFX shot that is subpar. It’s unfair to assume that the VFX guys must simply do anything that you dictate. There’s a constant line of communication that needs to be managed between the editor and VFX to achieve the best looking visual effects in the movie.

HULLFISH: Jonny Elwyn asked me what I learned from writing my Art of the Cut book and that’s my main takeaway: I needed to set my ego aside much more than I do in the edit room.

REFOUA: Yeah. By the way, you did a great job on that book. I have it. I like the format.

HULLFISH: Well, thank you very much. Was Michael the arbiter of who started out with a scene or did you guys choose between you? Or a post-sup?

REFOUA: Sometimes Michael would say I want a certain editor to work on a specific scene because he felt that editor was stronger at this or that. For example, because Debra had done all these comedies, he would ask her to do certain comedy passes. But generally, we just picked between us what scenes we each wanted to do. We all talked about the sequences and showed them to each other for feedback. It was very good to hear what other editors had to say and have the chance to implement notes from colleagues before showing it to Michael.

HULLFISH: I can understand how four or five editors work on scenes, but then the story starts coming together as a whole… The movie starts coming together in sequence and reels and as one cohesive piece. How did the editors work when it got to that stage? Even though people are working on separate sequences you still have to look at the whole film and say, “What happens?”

REFOUA: Michael would look at the reels and say, “I want this to be faster. I want this to be slower.” His notes just like anything else. And we would also go through the movie on our own. I would look at a whole reel and say to the other editors, “Don’t you think we should do this?” or “Don’t you think we should do that?” There was a lot of back and forth amongst editorial. We discussed things a lot. I don’t know if it’s the most efficient way to do it but it’s just the way we did it and it was rewarding because you engage other editors. And you get to see what they think and the ideas they come up with.

GERSTEL: We would watch a screening of the film and we would have a couple of pages of notes that we would go through. We would take sections of the movie to work on separately and put it all back together again.

NEIL-FISHER: We had an area in the Avid where we would put things in and we’d make sure that he saw it and we’d say, “Here’s my version. Here’s what I thought it should be.” We were always against the time pressure of when are we going to screen it next and what version of that scene he would prefer. So then we’d sit with him and go through our individual versions.

GERSTEL: We would have this version of the movie that was at the top of the project and we had a special bin and he would say, “This can go in… no, I want to work on this more… that can go in…”

HULLFISH: I’m really interested in that workflow. So at the top of the Avid project folder, there’s a specific bin for Michael to look at and then stuff would get moved from that bin into the main movie once it had been approved and chosen?

NEIL-FISHER: He literally wrote “PUT IN” next to that cut. And we had an amazing group of assistants that helped navigate through all this material and all these cuts and to keep them straight at all times because it could get quite confusing: what was current what wasn’t current. We kept his bin very current and we would archive all the old cuts because Michael would remember them and say, “You know the cut you did a couple of weeks ago?” He would ask for that again and we would have to go find it and our assistants knew exactly where that was.

HULLFISH: Beyond keeping 3 million feet of film and VFX organized, it’s enough of a nightmare just with one editor working through their own revisions.

GERSTEL: Also keeping in sync. three or four separate ISISes.

HULLFISH: Wow. So there were multiple ISISes in different locations?

GERSTEL: Yes. Michael has a home in Miami and a home in L.A. Both have an ISIS. We have an ISIS in the main building at Bay Films and there’s another in a separate building that Debra was in and while Michael was on location, shooting, there was an ISIS wherever he was plus when Mark was in London there was an ISIS there. In addition, Michael had a “travel Avid” which had a RAID with all the footage as well.

NEIL-FISHER: All of these had to be synced with each other and updated, including with all of the visual effects that were coming in. Every version of visual effects, every render, every everything had to be added because if Michael looked at something and something you did that required a render wasn’t there then he wouldn’t be able to see it. The assistants had to make sure all of that was up to date.

HULLFISH: I don’t want to think about the complexity of that syncing.

GERSTEL: The assistants were really rock stars. We had the best assistants to be able to handle all of that.

HULLFISH: With one editor and one director you’ve kind of got a unified editorial vision and then the director can speak to that. You guys didn’t really have that because there were so many of you. What did that do to the film that there were so many editorial voices?

NEIL-FISHER: There were a lot of editorial opinions but I think the one editorial voice is Michael’s that we’re all serving. We all have opinions and ideas but we were obviously all focusing on what does Michael want, what is he looking for. As you do on any picture, work for the director. Figure out what his take is on this material and his vision and then help him reach that goal.

GERSTEL: He was the ultimate filter. Although we all had our own colors and our own opinions it all filtered through Michael. So it became a cohesive patchwork because he shaped it in the end so it didn’t fit into the puzzle until he put his stamp on it.

HULLFISH: Anything specific about collaborating with Michael that was informative to your own editorial style?

NEIL-FISHER: He’s just full of energy. He’s full of energy in his work and in life. And that’s something that carries through the whole process. All of us working together may have certain ways of working, but Michael drove this whole thing.

GERSTEL: I took away that there are so many different ways to look at something. I’ve never re-thought a scene so many times. It is always, “What can be the better version? … there’s always the better way to do it.

NEIL-FISHER: Yeah. keep on pushing the material.

GERSTEL: And this type of material is incredibly flexible. He really does anchor to practical photography, special effects, and the human characters. But at the same time, there’s quite a lot of room via the visual effects and the robots. So scenes can be really restructured and this film is the most flexible I’ve ever seen. So you can completely restructure. You can interweave them in all different ways. You are never tied to the first take. You’re never tied to the script. It was a great benefit. It’s also a huge challenge because the possibilities are almost limitless.

HULLFISH: You mentioned that you had to use your imagination a lot on this especially where robots were concerned. And one of the things John mentioned to me that I thought was really interesting was that he used sound effects a lot of times to help him with his imagination whether it’s robot stomps or the sound of a robot transforming. Just the sound itself would help.

GERSTEL: Yeah. We have nothing visually. They don’t use any sort of temp comps. Michael has it all in his head. And in fact, putting something in there that’s not what’s in his head is more distracting. So sound was a huge, huge tool to pace the scene. I mean, how long does it take for the robot to fall down? We would have conversations about physics and so you would use sound to tell that story and be able to feel that it’s right because you don’t know what’s there until the visual effects come back.

HULLFISH: So no pre-viz or post-viz at all?

GERSTEL: Very, very little.

NEIL-FISHER: Sometimes Michael didn’t like the pre-viz or it wasn’t exactly as he’d imagined, so he’d rather it not be in.

GERSTEL: The scene had to be right before it got turned over to visual effects and that’s when you got animation.

SANGER: In the old days pre-vis was a necessity because the work all had to be budgeted prior to shoot and then strictly adhered to on set. Nowadays on the really big movies, I find directors often don’t stick to it so closely. It has become more of a rough gauge. Now when directors get to the set they know that there is some inspiration that happens during shoot where they may want to change things and nowadays they have more of the ability to do that: for better or worse.

Without pre-viz, you are often put in a position of having no dailies and being told, “Go cut a scene.” So with my VFX background, I can say, “I know what Michael will want” so I can edit something together using the previz as a foundation that will inform the visual effects team. So often you’re cutting together a framework that will inform what a sequence could ultimately be like and they’ll pick it up from there. You do have to have a great director like Michael in order to manage that. Because in the wrong hands what you get is laziness.

HULLFISH: Without the use of pre-viz or post viz were sound effects helping you to imagine the scene better and pace the scene?

SANGER: I don’t work that way. The first pass of the scene will be with the mute button pressed. I’ll cut the scene with no sound whatsoever. And then when I’m really happy with that I’ll bring the sound back in and I’ll listen to the dialogue and make any adjustments based on the dialogue. And frankly the sound effects and the music I put on frankly for the studio so they can see ultimately that it’s going to be a movie. Because we have those tools to do it and so we do. But for me, if a scene doesn’t work visually with no sound or dialogue… if you can’t play the scene through on mute without depending upon the sound and music to carry it then something’s wrong.

HULLFISH: Did you find that you were needing to recut stuff once animation came back?

GERSTEL: In fact, visual effects would come back and Michael would say, “Ignore the animation. What you see I’m not happy with it.” So you’re constantly recutting and going back to the fresh plates. Or an animator might come up with something that informs a whole new idea and now you’re going back to dailies to try to accommodate that idea.

HULLFISH: With so much action and VFX did you guys have to make a conscious effort to make or expand those moments of personal connection or understanding character?

NEIL-FISHER: It’s sort of built into the script, the personal moments for the characters. But it is a balance between those two things. And that’s certainly a Michael Bay movie.

HULLFISH: You were just talking about how malleable the scenes were so I was trying to figure out whether even outside of the script whether you were trying to make a conscious effort to say, “Oh my gosh, there’s so much action, we just need to have a moment of connection right here.”

GERSTEL: Just like any other film, we’re focusing on characters and whether that character is serving the film and whether their arc works.

NEIL-FISHER: How they’re motivated.

GERSTEL: Yeah. So all of those are certainly considerations, and because it is practically photographed film, it’s not like it’s ALL CG, there’s plenty of humans in it, and he also does a lot of ad libs too. So, a scene may be written in a certain way but he’s not tied to it. Especially on the comedy pieces, you get tons of different takes and ideas as Michael will let the actors just explore and come up with different ways.

HULLFISH: Would you like to speak to that ad-libbing, Deb?

NEIL-FISHER: You can see where Michael took the actors off on a tangent and it lent to a few different versions of the comedy. It expanded those moments and was fun to work on.

HULLFISH: On the score, I know Steve Jablonsky did all the previous movies. Did you guys stay in his musical universe or expand temp outside of his universe?

GERSTEL: He was actually on very early. Michael wanted to bring him on as early as he could. So he was providing us with actual score early on and temp music … Michael has a very, very specific ear for what he wants and you do stay in that world. Stay in that Steve Joblonsky/Hans Zimmer world.

NEIL-FISHER: And Michael did not want to use the old Transformers music.

GERSTEL: Yes. Stay in the “Steve” world MINUS Transformers. He wanted this to be a fresh take. This is not the fifth movie. It is more akin to a new version. We’re really delving into the history of Transformers. There’s a lot of new ideas in this movie. And so musically speaking he also wanted to kind of set it apart.

HULLFISH: So, no Transformers music but Steve Jablonsky music. Well, he’s got a big enough body of work.

GERSTEL: There was plenty to go to.

HULLFISH: Adam, you said there were so many re-cuts of scenes, so did you sometimes say, “Well, maybe I should just approach it differently from the beginning where I don’t approach it in the same way I did last time… whether that was using a selects reel or some other method?

GERSTEL: When I’m cutting a scene fresh from dailies I would do a selects reel, but if I was re-cutting I wouldn’t really go to a selects reel. I would go directly to dailies and work my way through it.

NEIL-FISHER: I tend to not look at other people’s cuts right away and then I cut a version and then go look to see how someone else approached it too. I tend to do what you’re saying which is to look at a scene myself and do a version and then I say, “So, what did everybody else do and what’s going to make it different.”

GERSTEL: I was on from day one of photography so I really did have a selects reel for every scene in the movie.

NEIL-FISHER: For me, it inspires a cut, going through the selects reel.

GERSTEL: The good moments — whether or not they go together — they’re always the good moments, then you figure out how to put them together.

HULLFISH: So, you guys would have multiple selects reels then I would guess. Even once a single editor cuts a selects reel you still make another version of it to boil it down a little bit.

HULLFISH: Did each person have their own assistant or were there just a couple of assistants?

REFOUA: There were five editors working and at one point there were up to seven editors but there were always four assistants.

HULLFISH: You mentioned that Michael delivers his own selects reels. Does he pull them himself or does he have an assistant that helps him?

REFOUA: No. He operates the Avid. He’ll go through the dailies himself and just build a reel and then send it to us. He doesn’t have to be precise. Sometimes he would actually play around with a scene and then say, “I played around with this. Can you fix it?”

NEIL-FISHER: And there were Michael’s selects on top of that.

GERSTEL: Dupe detection became a real friend. You would have just finished cutting and then: Oh, Michael’s got a selects reel ready!” So you would check it out to see what he thinks. So you could take his selects reel, throw it at the end of the sequence and then you get a little color light up on each repeated shot so you’d know if he also had it as a select.

HULLFISH: I had actually heard of somebody else doing the same thing with a director where the director would make a selects reel and they would use dupe detection to see how many of the selects made it to the scene that had been cut previously. Very interesting idea. It was a way for the director to visually see how on track the editor was with their own idea of the scene.

GERSTEL: He definitely had a very specific reason for picking things. So you have to really compare and find out why he picked something.

NEIL-FISHER: Plus you can discuss his selects with him intelligently when you do watch your version of a scene.

GERSTEL: “Speaking intelligently” is a good way to put it because after the end of a day Michael would say, “OK, what do you think about that? You can’t just say, “Oh, I thought it was great.” Because he’d say, “Why? Why was it great?” And he’d really want to discuss what the options are, why they’re good, and even how the could be better.

NEIL-FISHER: And what you liked, what stood out…

HULLFISH: How do sound effects change the pacing or rhythm of a scene?

NEIL-FISHER: I always cut with sound effects personally and present my cuts with sound effects and music, I just feel like that’s the better way to present the cut that I’m selling to whoever it is that I’m selling to. So it’s part of my workflow and we have a ton of sound effects loaded into the Avid. The sound team has worked with Michael for years and they are so on it from the beginning: any requests we have they were always right there with whatever we needed.

GERSTEL: I can’t tell if a scene is working until it has sound effects and music. It really helps you understand the pacing. I have to smooth sound out in general before I can even tell if a cut is working. So I’m always presenting a refined cut.

HULLFISH: Talk to me a little about sound effects. Do you like adding them yourself? Was there enough of an audio team that you didn’t have to worry about that?

REFOUA: On this one, I put in sound effects in the beginning or if a note required it. You have these plates of soldiers or stunt men rolling over, falling down, fighting, with explosions going on and then there’s supposed to be a robot that will be added later. The sound effects were how we sort of indicated the robot action before the animation passes would come in. Here’s the sound of a robot transforming. Here’s the sound of the robot walking. Once we got past that stage we had one assistant, Joe Galdo, who actually got a well-deserved associate editor credit, responsible for communicating to the sound department and to music and cutting in the sound effects and updating everything for sound and music. He was also the liaison between Michael, the editorial team and the sound department. Joe was fantastic. All of the assistants were fantastic. They worked crazy hours every day.

HULLFISH: Then there’s probably a VFX editor in there someplace I’m assuming in addition to the assistants.

REFOUA: The funny thing is I brought on a first that I’ve worked with before, Steve Bobertz. All of the assistants were in one room together and they sort of, among themselves, split up who’s going to do what and Steve, who’s been a first on many movies, took care of the visual effects. Actually, I think this time, his credit is VFX editor.

HULLFISH: What about temp music? I know Steve Jablonsky did the score and he’d done scores for the previous movies. Did you guys try to stay within his musical universe?

REFOUA: Yeah. Fortunately, he’s done a lot of movies so we’d try to pick stuff from what he had done.

HULLFISH: Did he provide additional cues that maybe he’d done that had never seen the light of day? Kind of like a stock a library of his own music or were you working just from the actual soundtracks.

REFOUA: His music editors gave us the tracks that were used in all the different movies, which is not something you can buy on a CD. We had access to all that stuff, which was very good.

HULLFISH: That’s nice. Was there a music editor on the movie?

REFOUA: At a certain point, we had a few music editors constantly changing and modifying the score to reflect Michael´s notes.

HULLFISH: What was that interaction like. Were you cutting stuff in or were you just leaving it to somebody else?

REFOUA: We always cut music and sound effects in ourselves. Sometimes, if I didn’t have time, I’d ask Joe, “Hey, can you put some music to this?” And since he’s worked with Michael for 10 years, he was very familiar with the kind of stuff Michael would like so he would do the work, if he had the time. Once we started screening the movie for Michael and ourselves, the music editors and Joe took over.

HULLFISH: Some of the folks that started out on cutting on film say they kind of miss the days when you could not have to stick a temp score in or that your picture cut needed some imagination for a studio executive to watch to know that was going to work.

NEIL-FISHER: That might be of a time when people didn’t do it and it was not expected but I have just always cut that way. I always assume that people are not going to use their imagination well enough to understand the cut. Maybe it’s because I started working in commercials and we always had to sell the client on the cut that I just always did it from the beginning. It’s just the way I work.

GERSTEL: Likewise for me. I have never worked in a world where it was an option to NOT cut in sound effects and music.

HULLFISH: I’ve talked to now almost 100 editors. There are still directors who will wait all the way until the first audience screening before they want to hear music in a cut. I think it’s rare for most people, but it does still happen. Everybody needs to have that music in there at least by the time you start doing screenings, but the director’s cut sometimes you get all the way through a director’s cut without temp music. Anything else that you’re going to take away or some revelation about editing that you learned from this group of editors?

GERSTEL: I just think that this was such a collaborative process. I enjoyed working with my fellow editors so greatly. We all really had great relationships. I just take away this really wonderful experience of working as a team.

NEIL-FISHER: Yeah, a non-competitive, collaborative effort and really a great experience.

HULLFISH: Did you learn any new techniques or ideas from your fellow editors?

REFOUA: Yes. You know that was an interesting thing, because a scene I’d worked on, someone else would work on and afterward you could see: “That’s why he did it this way.” We talked about things all the time. There were four of us for a while and then five of us and we talked about what we thought Michael wants and deal with the notes that Michael had given us and try to interpret them. So that was really good. There was constant communication between all of us.

HULLFISH: Can you think of a big takeaway to your editorial style or approach to anything that you got from one of our your fellow editors or from working with Michael Bay.

SANGER: The list is endless. It really is endless because the collaborative efforts of the whole team, you could not help but soak up editorial styles, technical shortcuts, habits that the other guys picked up. Certainly in the case of the editors just being in the same room as them I don’t think it’s arrogant to say that we were all learning off each other. And that was joyous. Take away from working with Michael? Again the list is endless. It was very interesting to see his method of how he goes through his decision-making process of what to use and what to disregard. Just seeing how a director with such a huge back catalog of movies makes his decisions. His decision-making process is something that so many people will never get the opportunity to see.

These three interviews – more than 10,000 words were all transcribed with SpeedScriber – in just minutes.

These three interviews – more than 10,000 words were all transcribed with SpeedScriber – in just minutes.

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish

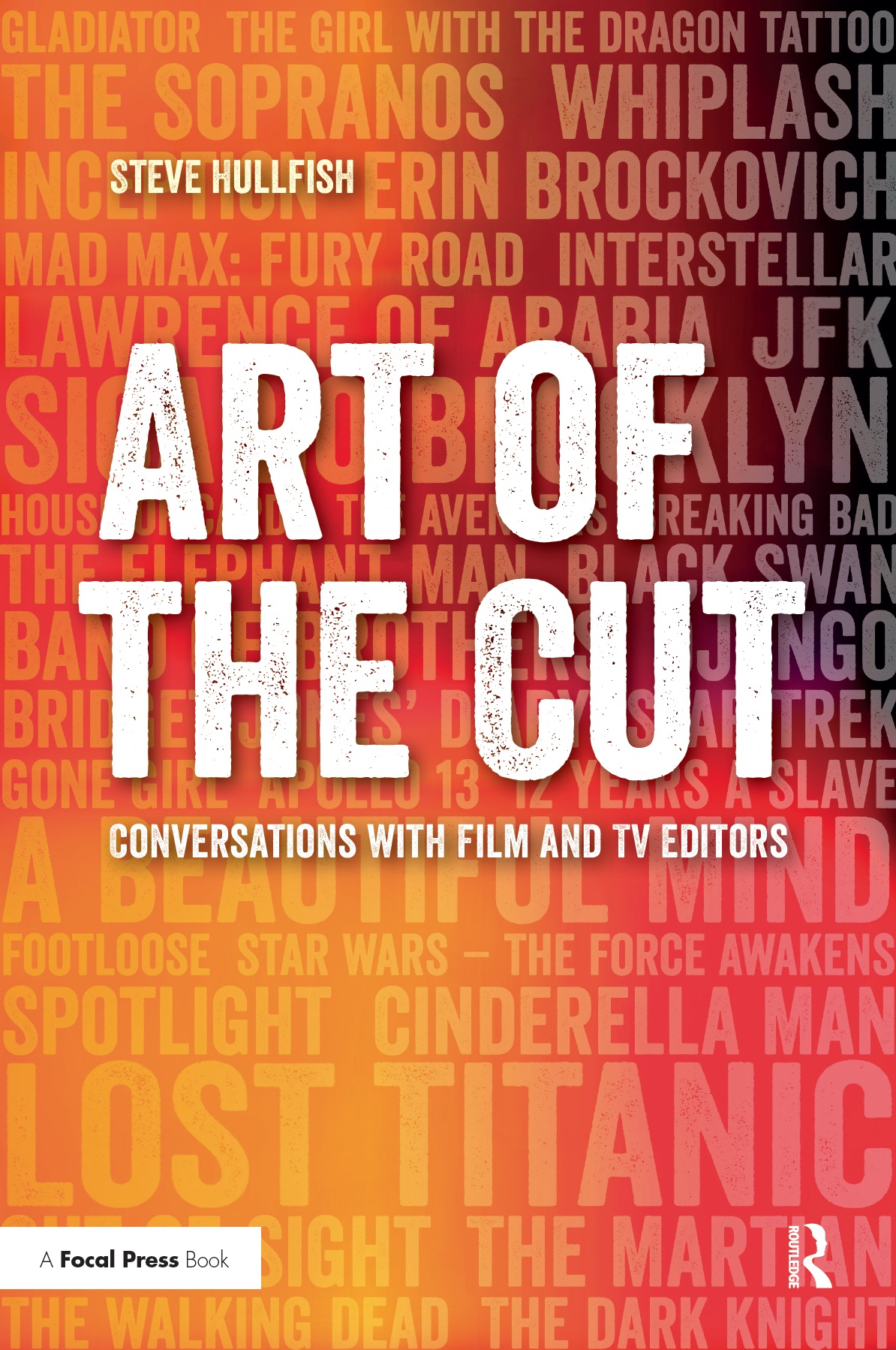

The first 50 Art of the Cut interviews have been curated into a book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV editors.” The book is not merely a collection of interviews, but was edited into topics that read like a massive, virtual roundtable discussion of some of the most important topics to editors everywhere: storytelling, pacing, rhythm, collaboration with directors, approach to a scene and more. Oscar nominee, Dody Dorn, ACE, said of the book: “Congratulations on putting together such a wonderful book. I can see why so many editors enjoy talking with you. The depth and insightfulness of your questions makes the answers so much more interesting than the garden variety interview. It is truly a wonderful resource for anyone who is in love with or fascinated by the alchemy of editing.” In CinemaEditor magazine, Jack Tucker, ACE, writes: “Steve Hullfish asks questions that only an editor would know to ask. … It is to his credit that Hullfish has created an editing manual similar to the camera manual that ASC has published for many years and can be found in almost any back pocket of members of the camera crew. … Art of the Cut may indeed be the essential tool for the cutting room. Here is a reference where you can immediately see how our contemporaries deal with the complexities of editing a film. … Hullfish’s book is an awesome piece of text editing itself. The results make me recommend it to all. I am placing this book on my shelf of editing books and I urge others to do the same.”

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now