Kevin Ross and Dean Zimmerman are the editors behind the cultural phenomenon that is Stranger Things. If you haven’t binge watched this series yet, I suggest heading over to Netflix and starting a mini-marathon now – there are only eight episodes in season one. Dean Zimmerman’s credits include Night At the Museum 3, Night at the Museum: Battle for the Smithsonian, Date Night, and Rush Hour 3. Several of Dean’s previous movies were directed by one of Stranger Things’ directors, Shawn Levy. The Zimmerman family is an editorial dynasty. Dean’s twin brother, Dan, was interviewed on Art of the Cut for Mazerunner. And their dad is a long-time Hollywood editor. Kevin edited Halt and Catch Fire, Californication, Men of a Certain Age, and Shameless, among others. He’s also been an associate, additional or VFX editor on films like Lawnmower Man, The Truman Show, and Vanilla Sky. He is currently working on season 2 of Stranger Things.

HULLFISH: One of the things that fascinates me, and you guys are great to talk about this, is the way that multiple editors collaborate – although I’m assuming you were on separate episodes, correct?

ZIMMERMAN: (joking) We were, and I hate Kevin, so I didn’t ever want to talk to him.

ROSS: …and I had to move to a different building because I just couldn’t stand Dean.

ROSS: Actually, we each had our own episodes and we talked to each other about them, but we never really shared much information because they were self-contained.

HULLFISH: Tell me a little bit about the schedule. In general terms, can you remember when principal photography was, and then how long you had to get each stage of the edit complete?

ROSS: They flew all of editorial to Atlanta, the first week of October 2015, so that we could work directly with the Duffer Brothers (Matt and Ross, the directors/showrunners) while they were in production on episodes one and two. They cross-boarded every two episodes, so each day Dean and I would get dailies for our particular episode. He did one, I did two, and it just depended on the production schedule who was going to get the most footage that day or what scenes. And then on those first two episodes, we had to turn it over to show the Duffers pretty quickly because we wanted to make sure that everything was working out and that they were happy with our edits. But they had 21 days to shoot?

ZIMMERMAN: Yeah, it was on average about 21-22 days to shoot 2 episodes at the same time.

HULLFISH: And then so you guys were obviously keeping up with production during those 21 days, and then 5 or 6 days to get an editor’s cut or no?

https://youtu.be/b9EkMc79ZSU

ZIMMERMAN: It was an interesting thing because coming from feature world I’m used to lots of material and getting through it pretty quick. So, I was pretty well done by the time they finished shooting. I needed a day or two to polish my assembly with sound and music and then started working with the Duffer brothers. I showed them my episode and they were incredibly happy. Because Matt and Ross were the showrunners, executive producers, directors, and writers they knew exactly what they wanted. We spent the first day tweaking the picture—which is not a lot of time considering it was a one-hour episode but I had the cut in such good shape that is all we needed to get a locked cut—and then the rest of the time was really sound effects and music – really fine-tuning that stuff. Then they would bounce back and forth from mine and Kevin’s room. It was a really smooth, very feature-esque process, and I say feature-esque because Netflix is fairly new to the game of original content so we were trying to help them with their pipeline. We were trying to utilize all of our experience and make a cohesive workflow that would utilize everyone’s time in the most productive manner.

ROSS: The normal television schedule would be to shoot an episode in 8 days and then the editor usually has 4 days to get their editor’s cut ready, then you do the director’s cut. On “Stranger Things” since we had such a long time and we were splitting up material every day, our cuts were pretty much ready to go right at the end of the first set of production dates. Dean was ready to go on day one. My episode was ready a day later. After the first two episodes, Sean Levy took over and directed episodes three and four, so while he was directing episodes three and four—and we were getting dailies on those episodes—we were able to still work with Duffers on episodes one and two so they could have them ready to show to Netflix before Christmas, which was an important step.

HULLFISH: Is there anything different, Kevin, other than the schedule in dealing with Netflix as opposed to a network?

HULLFISH: Is there anything different, Kevin, other than the schedule in dealing with Netflix as opposed to a network?

ROSS: It really is all about the schedule. The workflow was created by Rand Geiger, our producer of post. He tried to make it as much like a feature as he could. We mixed all episodes at the end of post—twenty-eight straight days of mixing—and that just never happens in television.

ZIMMERMAN: We basically treated the entire series as this big feature film that we broke up into what was considered back in the old days “reels.” For us, it was great because we did all our mixing and color-timing on the back end once all the episodes were locked and completed and all the visual effects were done. It allowed us that flexibility of being able to watch the entire series and go back into respective episodes and really fine-tune this basically eight-hour movie, which I think paid huge dividends in the storytelling, especially with the Duffers being such prolific writers. It was an amazing experience and Netflix is paving the way. Having all the episodes drop at once and not having to hit an airdate really yielded the most creative process. To be able to have that time and really fine-tune your craft and really fine-tune the storytelling was such a blessing. It was so wonderful to be a part of such a creative and collaborative process.

HULLFISH: It’s cool that you were able to do the color correction and the mixing all at the same time to give it a nice cohesive feel.

ZIMMERMAN: Exactly. Everything was so well-thought out by our Co-Producer Rand Gieger and Post Supervisor Josh Hegmann, with some input coming from me and Kevin, that rally made the perfect recipe for success. To be able to have that continuity and have that uniformity of sound and color at the end is what brings it all together. It was the same process for music. We had the band “Survive” which was such a key, integral role of the whole series that the Duffer Brothers fought for so hard. The Duffers were going to live and die by this decision of hiring this synth band out of Texas and they could not have hit a bigger homerun. It was such a great, unique experience because we had them on from the beginning. We were able to turn over cut scenes to them, have them score them, send them back to us, give notes, tweak… Like I said, the workflow and the creative process on this movie was so intense but worked effortlessly.

ROSS: Not only was sound happening at the same time as color-correction, it was in the same building, directly across the hall from each other, so the Duffers were able to walk back and forth. It was all done at Technicolor in Hollywood – a very convenient set-up.

HULLFISH: To jump back…the name of the band that did the score was Survive?

HULLFISH: To jump back…the name of the band that did the score was Survive?

ROSS: Survive.

HULLFISH: Did you do any temp music at all?

ROSS: Survive sent these sample cues to the Duffers, and it was hours and hours of cues. We had this massive amount of their temp material that then we would drop in and try to score scenes with. And when we got it close, and after the Duffers changed things or approved what we had, we’d then send that to Survive and they would shape their music more to the moment.

ZIMMERMAN: They sent us 121 cues right off the bat. Then we would pick three, four, five, eight of them at a time and layer them in and almost compose the soundtrack and try to make it what we’re used to—having an orchestral score that had the right tone for a particular scene. For us being able to add things here and there and then also integrate sound effects in with that… We spent probably as much time cutting picture as we did sound effects and music along with our incredible assistants.

ROSS: Kat Naranjo was my assistant, and she was absolutely terrific on this.

ROSS: Kat Naranjo was my assistant, and she was absolutely terrific on this.

ZIMMERMAN: Nat Fuller was mine. They were constantly tweaking music and integrating the two. To the Duffers’ credit, they really wanted everything that was to be presented polished in all aspects and have their vision shown exactly as they envisioned it.

ROSS: Our Music Supervisor Nora Felder also came through with really great source cues. She found us wonderful choices for scenes. Our EP, and director, Shawn Levy found the cue at the end of episode three, which is a cover version of David Bowie’s “Heroes” performed by Peter Gabriel. We were having such difficulty finding the right song for the emotion that we wanted—this is when they pull Will’s body out of the quarry—and one weekend he came in and said, “I think this cue is going to work. This has got to be it.” And even though the Duffers originally said no strings, once they heard that cue they made an exception. It really sold that moment.

HULLFISH: You mentioned sound design—obviously with horror I think that a lot of the tension and the feeling is coming from that sound design. Talk to me a little bit about sound design in a horror series.

HULLFISH: You mentioned sound design—obviously with horror I think that a lot of the tension and the feeling is coming from that sound design. Talk to me a little bit about sound design in a horror series.

ZIMMERMAN: For me, it was taking that feature model that I work with all the time. So, when we started shooting we had our sound designer, Craig Henighan, who is the most brilliant untapped talent in Hollywood in my opinion, work alongside us designing these amazing sounds, ambiances and transitions. The Duffer Brothers really love these kinds of Edgar Wright sound transition effects, which have become a huge signature for the series that we’re super proud of. As we kept cutting we would go to these specific Edgar Wright-esque transitions and we would need Craig to enhance them and really make them what they are today. Having him on from the very beginning was so important to everything that we did with sound, music and even color timing.

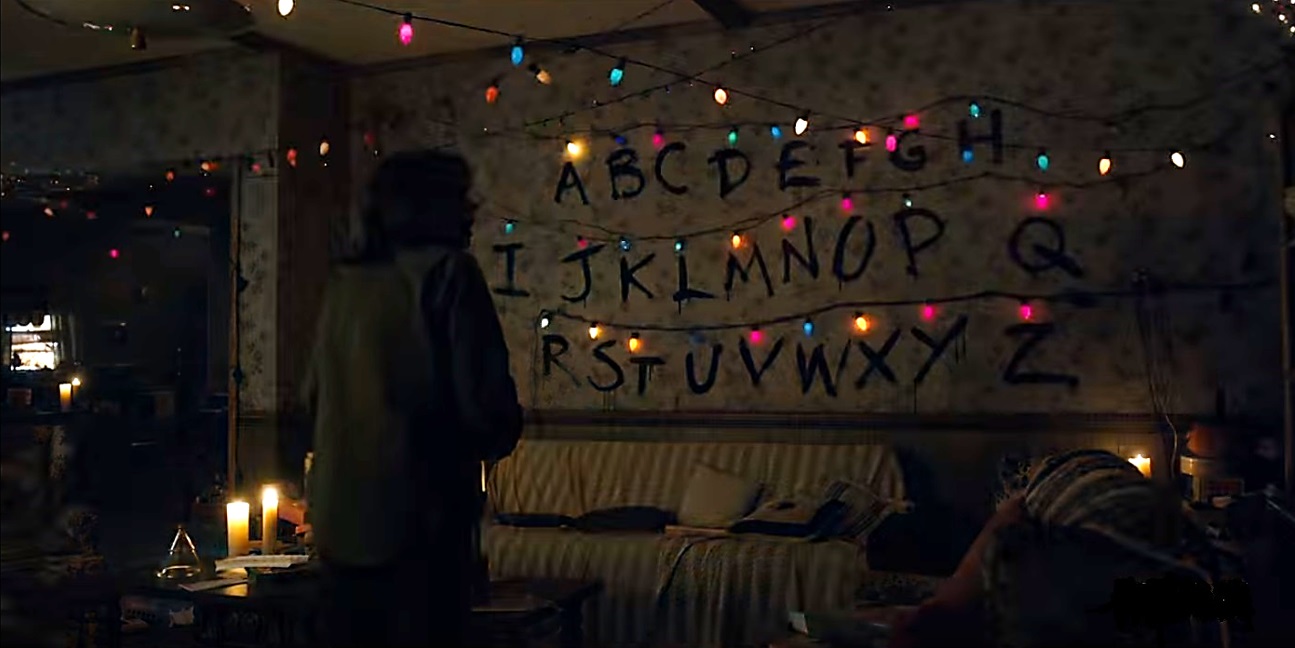

ZIMMERMAN: The nostalgia feel and the cultural phenomenon that “Stranger Things” became was pretty cool. We had a makeshift screening room in our editorial suites that we converted to resemble the basement of the Wheeler’s house. We had the Christmas lights on the walls and 80s posters everywhere, the Millennium Falcon, a little Yoda, to a real Atari that was hooked up to our 4K digital TV. It was hysterical!

ROSS: The guy behind all that was the Post Supervisor, Josh Hegmann. He even made fake dungeon and dragons graphic maps and charts and had them laid out on the table so if anybody came in, he had the dice to roll and whole D&D setup.

ROSS: The guy behind all that was the Post Supervisor, Josh Hegmann. He even made fake dungeon and dragons graphic maps and charts and had them laid out on the table so if anybody came in, he had the dice to roll and whole D&D setup.

ZIMMERMAN: They ordered the Sports Illustrated from 1983, the TV Guide from 1983. We actually had those original copies sitting on our coffee table in our little 80s basement…

ROSS: …and a Farrah Fawcett poster.

ZIMMERMAN: Exactly, with our state-of-the-art AVID Media Composer and our 65-inch 4K flat screen. It was pretty awesome.

HULLFISH: Since you’re kind of talking about it being a social phenomenon—you guys had to wait for that to happen.

ROSS: It absolutely blew me away when it happened because I’ve worked on a lot of quality television shows before, and when we finished “Stranger Things” we knew it was special, and we were very proud of it. We came out of there very satisfied with the final product, but then you wonder if people would find this show? To see how it took off on social media and became this cultural phenomenon? It’s mind-blowing, it really is.

ROSS: It absolutely blew me away when it happened because I’ve worked on a lot of quality television shows before, and when we finished “Stranger Things” we knew it was special, and we were very proud of it. We came out of there very satisfied with the final product, but then you wonder if people would find this show? To see how it took off on social media and became this cultural phenomenon? It’s mind-blowing, it really is.

ZIMMERMAN: And it’s so gratifying too. You put your blood, sweat, and tears into crafting these episodes. I’ve worked on some big features and I’ve never ever had the response that I’ve had from this series. I just couldn’t be prouder of it, and I couldn’t be more appreciative that I was able to be part of the journey.

ROSS: I don’t know about you Dean, but I’ve had so many people just glowing about this show.

ZIMMERMAN: I am such an advocate of Netflix. They just said, “Do your thing, do what you guys do best.” They were so filmmaker friendly. They really just want to put out incredible content. They put so much trust and faith into their filmmakers.

ROSS: Absolutely.

ROSS: Absolutely.

HULLFISH: You mentioned audio transitions. Can you guys give me a few examples of what those transitions were and how you originally constructed them or how either the Duffer Brothers or you guys conceived them?

ROSS: I would say my biggest one for me was whenever I was transitioning from the real world into The Upside Down or the void where Eleven would wake up. We relied on making the cut really happen by ramping up the audio or the sound effect into a rising growl and then it would cut to basically nothing and be completely silent when she would open her eyes in the black void.

ZIMMERMAN: And it’s interesting because we both had episodes where she goes into this black void.

ROSS: We never really looked at each other’s edits at that point.

ROSS: We never really looked at each other’s edits at that point.

ZIMMERMAN: No, we never did. When I first saw it I thought, “We should play this dead silent. I’m talking ZERO sound.” Kevin and I were as one in these big decision-making things, which just goes to show how in-sync and in-tune we were.

ROSS: I agree. This editing crew was so in-sync. There wasn’t a competition between us. We knew we were on a great show and we wanted to make it the best it could be and it turned out that we basically have the same ideas. Our cutting styles meshed really well.

ROSS: At the end of December we came back to LA to finish the rest of the season. After the Duffers wrapped episode eight they flew back to LA and they reviewed all the other episodes. We had a terrific edit bungalow in Hollywood, courtesy of Runway Editing. It felt like a house and we all just moved from room to room. Dean was down the hall from me and our assistants were across from us.

HULLFISH: Were you guys on a Nexis or a big Unity or something I’m assuming?

HULLFISH: Were you guys on a Nexis or a big Unity or something I’m assuming?

ZIMMERMAN: ISIS.

HULLFISH: Separate projects for each episode?

ROSS: Yes. That’s how it typically is in television. Each episode is a separate project.

ZIMMERMAN: And that’s where I really yielded to Kevin experience because with a feature film everything is in one big project. What we actually did was set up a sharing folder within every project so we didn’t have to exit out if we wanted to get an exterior shot from episode one and I was in episode eight. We had these very key folders within each project that would allow us access to anything that we did in the other episodes which was very handy.

HULLFISH: Did you guys have to have some kind of organizational system for tracks?

ZIMMERMAN: The assistants did.

ZIMMERMAN: The assistants did.

ROSS: I still like doing direct outs because that’s just the old school when I was an assistant and teaching feature editors how to use non-linear. I just like that method. When they were doing a live mix, they could pull different channels down.

ZIMMERMAN: I did direct out, too. I followed your lead.

ROSS: Okay you did direct out too. We didn’t split out the same number of tracks, but the assistants did.

HULLFISH: So, the assistants maybe fixed stuff later because I would think you’d want to go into a big mix with specific tracks used for specific reasons.

ROSS: You never mix these tracks in the final mix. These go over to sound and they split them out however they want. We’d have the first four channels for production dialogue, and then five through seven might be ADR or temp effects, and then there’s backgrounds, and then at the bottom are stereo music cues. But once it’s handed over to sound supervisors they split it out into a lot more tracks than that, so it didn’t really matter how many tracks we gave just so the order was correct.

HULLFISH: Let’s talk about approach. How do you watch dailies and how you approach a scene?

HULLFISH: Let’s talk about approach. How do you watch dailies and how you approach a scene?

ZIMMERMAN: I’ll read the script or that scene a couple times before I even watch any dailies so when I’m watching the dailies I know what I’m going to be doing. When I read a script or a scene I picture in my head how I am going to cut it and what I’m going to do. The process that works best for me is watching all the dailies from start to finish then go back and on the second viewing pull selects and pieces that I really like. Then if there’s a specific moment or a line that I really engage with sometimes I build scenes around that and the scene will flesh out from there.

I try to be as real and grounded as I can with my editing and let it just come from a very organic place.

ROSS: I’m like Dean in that whenever I read a script I mentally picture how that’s going to play out or how it’s going to cut. And then in television you quickly find that a lot of times you don’t get the coverage that you want or you need, but with the Duffers you’ve often got better coverage than you had in your head. I would watch the dailies and in the meantime, my assistant was using Avid’s script integration program, so I could quickly access each take of each read so that I could compare them against each other. I would sit with my script knowing that I wanted to be on a close-up of Winona at a specific point. Then I would use script integration to find the best one that I want to use. I would audition the takes that way. The script integration feature is great because when you’re in with producers or directors and they want to see the alternate versions, it’s a quick way to get to each take. You don’t have to go hunting for it. You have it right there. That’s the way I work.

HULLFISH: You use Script Integration, but not ScriptSync?

ROSS: Not a fan of ScriptSync – the automatic one where it does all the waveforms. Script Integration is manual labor for my assistant, but she’s really fast at it now. As a matter of fact when I do work on shows if I don’t have her as my assistant I’m looking for an assistant who’s good at scripting.

ROSS: What Script Integration is useful when you’re going to work with the producer and director, you just want to have that quick access to the material.

ZIMMERMAN: I would never use it for initially cutting a scene, but for changes it’s so invaluable and it really is incredibly fast. Back in the day we used KEM rolls where you would have your masters and then you would go into your coverage and your inserts and what have you. He would always have me organize the bins the way he would want them to be cut. I always use frame mode when I cut the initial assembly scene. I’m currently working on a new feature “Why Him?” and I will say I have been a convert to Script Integration. It is an incredible tool in regards to running lines for performance changes quickly. I came up having one of the best editors in the world – Don Zimmerman, ACE – in my very biased opinion – as my father. I credit everything to him. I was able to learn from such an incredible mentor and teacher. But moving from Film to the digital editing with Don was seamless because he was so open to expanding the creative process.

ZIMMERMAN: I would never use it for initially cutting a scene, but for changes it’s so invaluable and it really is incredibly fast. Back in the day we used KEM rolls where you would have your masters and then you would go into your coverage and your inserts and what have you. He would always have me organize the bins the way he would want them to be cut. I always use frame mode when I cut the initial assembly scene. I’m currently working on a new feature “Why Him?” and I will say I have been a convert to Script Integration. It is an incredible tool in regards to running lines for performance changes quickly. I came up having one of the best editors in the world – Don Zimmerman, ACE – in my very biased opinion – as my father. I credit everything to him. I was able to learn from such an incredible mentor and teacher. But moving from Film to the digital editing with Don was seamless because he was so open to expanding the creative process.

HULLFISH: Your brother mentioned that to me too. I think my bin layout is similar to what you’re describing – laying out visually the coverage with coverages grouped to find them easily, not necessarily in the order they were shot. Maybe the establishing shots at the top, then over-the-shoulders together from each side, then a row of close-ups, and maybe detail shots or specials below that.

ZIMMERMAN: Exactly. The way I would lay it out for my dad when he was editing is I would put all the masters first in a line on a single row and set the tile size and representative frame, and then we would go into the coverage. Like you said we would stack them. Everything would be on its own line, and it might take three or four bins to do a scene depending on how much footage you had. That’s how I normally set up the bins.

ZIMMERMAN: Exactly. The way I would lay it out for my dad when he was editing is I would put all the masters first in a line on a single row and set the tile size and representative frame, and then we would go into the coverage. Like you said we would stack them. Everything would be on its own line, and it might take three or four bins to do a scene depending on how much footage you had. That’s how I normally set up the bins.

ROSS: When I started doing Lightworks and Avid, that’s how I laid out my scenes. I would lay them out like KEM rolls. Start with the masters and the coverage and the mediums and the close-ups and I used to have my bins laid out like that and I would tell my assistants this is how I want it. The problem is in television, there are usually three editors and two assistants, so you never had your own assistant. One did the even episodes, one did the odds. And the biggest problem was if you tried to get that assistant to fix the bins the way you wanted, they never had time because they had other issues for other episodes they were dealing with, and so that was one of those concessions I had to make as a TV editor.

ROSS: I just want to say that even though I read so much online about “oh, this is an homage to that movie or that movie,” never once did the Duffers ever give us marching orders that this is a Goonies scene, so you’ve got to cut it this way.

ROSS: I just want to say that even though I read so much online about “oh, this is an homage to that movie or that movie,” never once did the Duffers ever give us marching orders that this is a Goonies scene, so you’ve got to cut it this way.

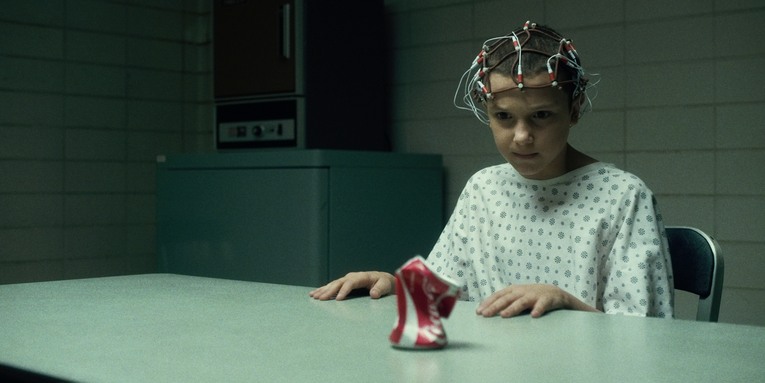

ZIMMERMAN: I was just watching this YouTube video where this guy was making these comparison’s when Eleven’s pointing out Will in your episode how that’s like a moment from the movie Witness. From my episode they showed Eleven and her liking Eggos and referenced the finding of E.T. to the moment at the very end of episode one where Eleven’s in the woods and it’s raining and the boys shine the flashlight in Eleven’s face. Not once did I ever reference E.T. I was never told to cut it that way. That’s just how it organically came out. That scene did not change from the day I cut it from dailies to where you’ve seen it on TV on Netflix.

ROSS: I remember! Did you even think it was the E.T. moment when you were cutting?

ZIMMERMAN: No!

ROSS: It wasn’t until I saw it in some webisode I went wait a minute. That’s an E.T. moment?

ZIMMERMAN: And the great thing is we didn’t know we were doing it, but clearly this is what the nostalgia factor means. We grew up with these films and I’ve seen E.T. probably 50 times, so maybe it was just ingrained in my DNA and when I saw that stuff it subconsciously came out, but that was not my intention at all to recreate that moment.

ZIMMERMAN: And the great thing is we didn’t know we were doing it, but clearly this is what the nostalgia factor means. We grew up with these films and I’ve seen E.T. probably 50 times, so maybe it was just ingrained in my DNA and when I saw that stuff it subconsciously came out, but that was not my intention at all to recreate that moment.

ROSS: That’s like the Witness moment for me when Eleven points at Will’s picture in Mike’s room and they kept saying it’s the Witness moment with Danny Glover and I was like, wait a second, it is! I had no idea I did it. And I never changed that edit from when I first cut it.

HULLFISH: Is it the shot or is it the cut, because the shot referencing Witness is certainly either a directorial or a writing thing.

ZIMMERMAN: No, it’s the cut! It’s literally going from the kid to the picture to the finger of the hand and that’s what they are referencing. And it’s the beams of the flashlight to Eleven’s face then back to the boys then back to Eleven. It was the cutting pattern that they were referencing as the nostalgic callbacks. The Duffer Brothers, Kevin and myself never went in with our intention of doing those kinds of recall nor did the script detail the scene to be cut that way.

ROSS: And we never discussed it with the Duffers once. I will say that I have worked with Peter Weir in the past and I watched Witness a couple of times just to be able to chat with him about it when we were on another show, but I didn’t even remember that scene when I was cutting that, so it’s a little strange.

ROSS: And we never discussed it with the Duffers once. I will say that I have worked with Peter Weir in the past and I watched Witness a couple of times just to be able to chat with him about it when we were on another show, but I didn’t even remember that scene when I was cutting that, so it’s a little strange.

ZIMMERMAN: Stranger Things.

HULLFISH: A communal editing mind is at work.

ZIMMERMAN: Right?

ROSS: I have to say one of the most original transition cuts that stands out to me is in episode five. The Duffers came up with it. It was when El was in the tank and she was getting ready to flash into the black void. And we changed the aspect ratio of the film and we kept squeezing it so it got tighter and tighter on her eyes so the top and bottom of the frame kept closing in and making it more claustrophobic. And that was one of those things when we were just cutting it in the room and Matt goes wouldn’t it be cool if you just kept pushing the matte on the top and bottom, tighter and tighter. And we tried it, and that’s been brought out in some of those examples on the web, but that was all Matt when he came up it.

HULLFISH: Interesting. I think I talked to Paul Crowder and they changed some aspect ratio stuff in the documentary he cut. Another editor had mentioned that in a certain aspect ratio show, obviously for you guys 16:9—or I don’t even know if that’s true—that they would change the aspect ratio on certain shots.

HULLFISH: Interesting. I think I talked to Paul Crowder and they changed some aspect ratio stuff in the documentary he cut. Another editor had mentioned that in a certain aspect ratio show, obviously for you guys 16:9—or I don’t even know if that’s true—that they would change the aspect ratio on certain shots.

ZIMMERMAN: It’s not uncommon nowadays. The tools that we have and the abilities with the digital world opens the door to being so much more creative and not being pegged in by certain things like frame and aspect ratio. Nothing matters anymore. We can slow things down, we can speed things up, we can make things tight, we can open things up. We shot this series 6K and we did a 4K center extraction from it so we had room all around what was the actual intended framing allowing us to create shots other than originally designed. With the 6K resolution we could take a wide shot and turn into a close-up. We literally didn’t have a single restriction, so we were able to do all these crazy things like these jump cut flashbacks and changing the aspect ratio. I think you’re going to see a lot more of that because people are going beyond the tradition of needing to stay within this box. Let’s knock down the walls, let’s open up the barrier and be able to be as creative as we can to tell the best story possible.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CKtq-bZgS8I

ROSS: And one of the greatest things I think about switching to non-linear for finishing on film is that now we can do so much with the frame itself, like with animattes. Dean’s the king of animattes. I would say I’m the prince of animattes. When I first switched over and was starting getting to cut, it was in television. I was coming from the feature world, and I remember the first time on a show someone said well just do a split frame and freeze the left side. And I was like wait, that’s an optical. I was still thinking “feature world” and finishing on film. They were like, “No. This is TV. You don’t have to finish on film. It just opened my mind to the fact that we can play with things that are going on the left or the right side of the frame like if someone is moving too much on the left side, slow them down so they’re still looking at whatever action is going on the right. Or you can marry a couple of shots and do a fake wipe of a body and you don’t have to worry about spending money for an optical to have that done on film. It just expanded the possibilities of everything you could do.

ZIMMERMAN: Not to mention the fact that sometimes you have this incredible performance on the left side of the frame and on the right side of the frame you’re like “Ugh, I can’t use that.” Now we’re able to cut that right-side performance out and replace it with a better one. You have an incredible performance equally matched with another incredible performance to give you this amazing shot that never existed—it existed as two separate pieces, but now it exists as a cohesive one. It’s that kind of stuff that you have the ability to do all the time now.

HULLFISH: And doing the split screen helps you make a better edit because otherwise the fix is to simply jump out of the two shot to a close-up, but sometimes you want to live on the two shot for a variety of reasons – whether that’s pacing or performance…

HULLFISH: And doing the split screen helps you make a better edit because otherwise the fix is to simply jump out of the two shot to a close-up, but sometimes you want to live on the two shot for a variety of reasons – whether that’s pacing or performance…

ZIMMERMAN: Exactly. It’s so nice to just live in a cut and live in a moment.

ROSS: As an example, on The Truman Show, we had a shot where we were on an over-the-shoulder of Jim Carrey on Laura Linney and she was giving a great performance, but on the right-side Jim Carrey happened to turn his head to look to his left or something, and we had to freeze frame him and order that as a $10,000 optical to make that shot work. Nowadays, you can do it with no cost.

HULLFISH: Were there issues with editing the kid actors?

ZIMMERMAN: In every job I find the biggest challenge is continuity. The only performance thing for me, and I don’t know if Kevin found this, was Mikes’ little sister Holly. Not that she was a bad actor in fact quite the opposite. I had a very big dinner table scene that was actually written as a dramatic scene but in reviewing dailies I decided to cut that scene as a comedy. Our main character, Will, had just disappeared and the boys were planning a mission to find him. The Sheriff instituted curfew and Mike’s mother enforced it along with having the teenage drama of Nancy wanting to go see her boyfriend that night not to mention a totally checked out father. Watching all this drama unfold was this sweet innocent baby Holly eating her dinner watching as if to say “What are you guys talking about?” It was at this moment I realized I had a huge opportunity to make this scene a comedy. Having this child be my comedic hinge changed the dynamic of the entire episode. I sent it to the Duffers we did not change a single frame of that scene because it just came out left field. They were expecting something totally different, and what I gave them was this very grounded, real family dynamic scene, but just interlaced with this comedy of this little girl. It was even to the point when Netflix first saw it they were like, “This little Holly girl’s going to get an Emmy for her performance.” They shot one take of her with three cameras. It was literally just her resetting and “post acting” stuff. That is where you sometimes find these nuggets of gold, especially in the comedy world. So we had to do a lot of split screening and some roto work to get some things out of there and make timings work perfect, but in the end the scene turned out so much better than it was on the written page.

ROSS: Holly is two and she was an identical twin. One of them had a better disposition than the other. In my dinner scene with all the kids around the table I also had to steal Holly moments from in-between action where she kinds of dips down into her highchair, just to cut to her for comedic relief. There’s one place I had used an Animatte to help the timing. And that’s the scene where Eleven is coming down the steps behind the parents where they’re all having dinner, and Dustin has to slam the table to draw everybody’s attention so that El can pass in the background. I think I Animatted El in the foreground on this long, wide shot so that the timing was better for her pass by. That’s one of those spots where I did use an animatte to split the screen.

ROSS: Holly is two and she was an identical twin. One of them had a better disposition than the other. In my dinner scene with all the kids around the table I also had to steal Holly moments from in-between action where she kinds of dips down into her highchair, just to cut to her for comedic relief. There’s one place I had used an Animatte to help the timing. And that’s the scene where Eleven is coming down the steps behind the parents where they’re all having dinner, and Dustin has to slam the table to draw everybody’s attention so that El can pass in the background. I think I Animatted El in the foreground on this long, wide shot so that the timing was better for her pass by. That’s one of those spots where I did use an animatte to split the screen.

HULLFISH: Let’s talk pacing.

ZIMMERMAN: As far as the general tone and direction, the Duffers really wanted this to be very snappy, very fast-paced. They wanted you to lean in and be on the edge of your seat the whole time. That was all very dictated in the directing and then translated to the cut. We didn’t let things lag too much, and when we did have it lag it was intentional. They weren’t afraid of quick cuts but they also loved staying in a scene if the performance was working. To be honest, it was how you read the script that really influenced the cut. As fast as you read it is as fast as we were cutting it.

ROSS: I had the outlier moments sometimes. Episode five was all about Will’s funeral. That was slower paced, because I felt like we have to linger on these a little bit longer and go a little bit slower because of the sadness and the melancholy that was going on. And the Duffers did like that. Now in episode seven, which is when everything starts to fall into place—all our groups comes together and they get El to the gym—that one was a longer episode and there was a longer bike chase, but then the Duffers were like let’s shorten this up and just get to the moment. They actually lopped off portions of the bike chase. If there were five sequences in the bike chase they took out two of them, so we only saw like one, three, and five, just to pace it up and get to the van flip in that episode. Those are things that I liked, but in the end, it didn’t really need to be in there. It was just more action that wasn’t necessary to tell a good story.

HULLFISH: There was a little bit of a different dynamic with the Duffers as showrunners and directors on the first couple episodes.

ZIMMERMAN: Having the directors be the executive producers, writers and show runners was invaluable because they had that final say. It was a united vision from the very start. That’s what made it so effortless to do notes and polish the episodes so quickly because we were all on the same page. It was a very smooth and easy process. We were able to get through the episodes at a really good clip, and then be able to go back and fine tune and tweak and really perfect everything.

ROSS: We were on the show between 33 and 36 weeks. That’s why coming from television, this was so anti-television in that it made me feel like I was back in the feature world — where I started — because you were dealing with directors who were completely in charge. And in television, since the director is generally just for hire, they come in, they shoot it, they give four days doing their director’s cut, and then they’re gone. They don’t ever give input again and the showrunner is the man who makes the decision. Everything the director may have done in television, a producer will come in and go let me see your editor’s cut, let’s change it back to that. They can wipe out all the changes the director has made. Here, it really was like a feature and you were back in the world of these guys are in charge. It was nice that the directors were the executive producers. And Shawn’s material just melded so perfectly with the Duffers’. It was seamless.

ZIMMERMAN: It was as if they were a collaborative unit as well. Just like Kevin and I were, but two completely separate entities. But it’s seamless. It’s like looking at some wallpaper that’s been perfectly put up. You can’t see the seams.

ZIMMERMAN: It was as if they were a collaborative unit as well. Just like Kevin and I were, but two completely separate entities. But it’s seamless. It’s like looking at some wallpaper that’s been perfectly put up. You can’t see the seams.

ROSS: Until the monster comes through and rips it apart.

ZIMMERMAN: Well, yes of course.

HULLFISH: And on that note, I think we can wrap this up! Thanks so much for your time, gentleman. Thanks for sharing.

ZIMMERMAN: It was a blast. I really appreciate the opportunity to share the process!

ROSS: Thanks so much for having us on Art of the Cut!

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now