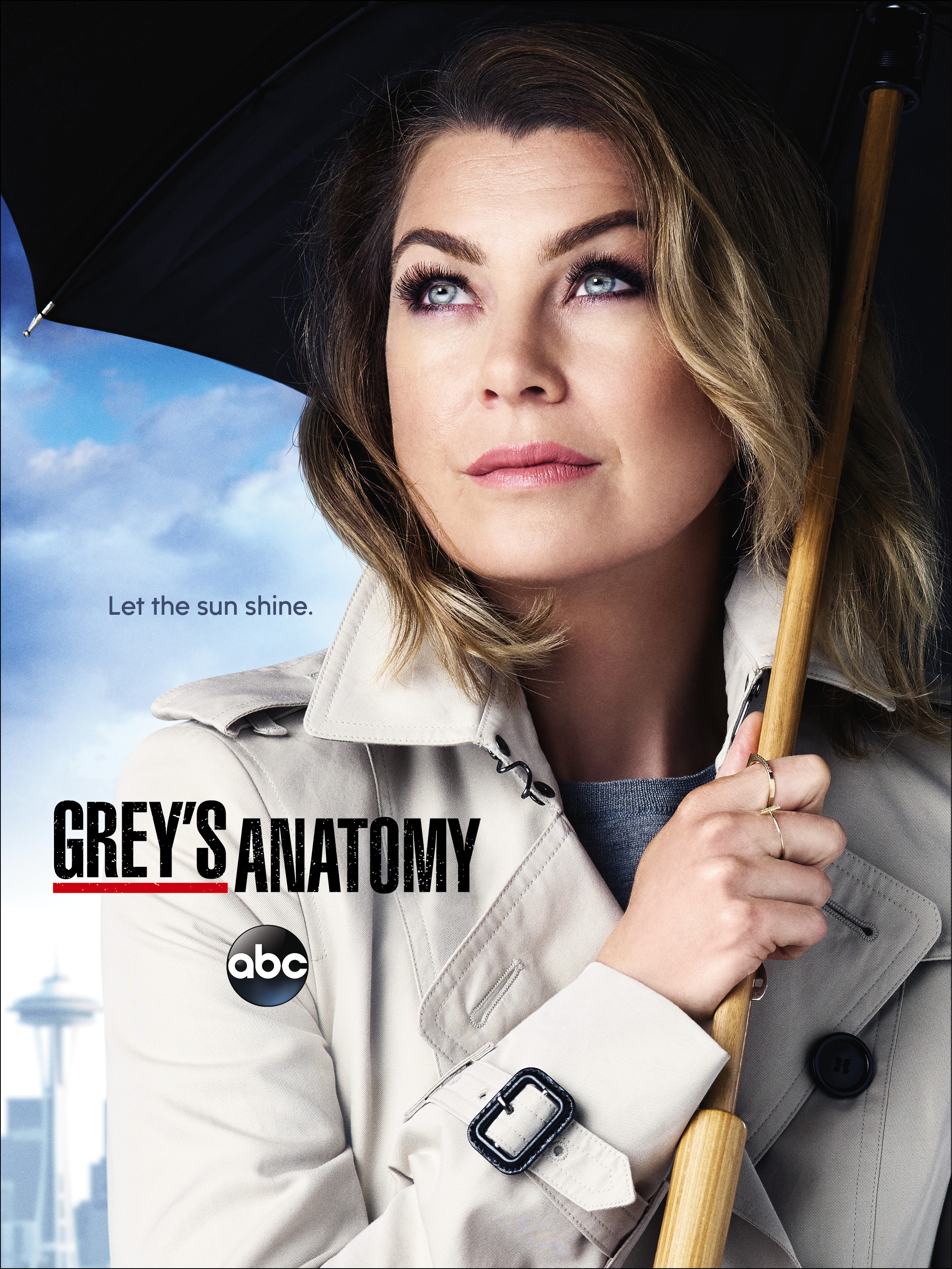

Today, Art of the Cut discusses cutting the long running hit TV series, “Grey’s Anatomy” with its lead editor, Joe Mitacek. Mitacek has cut about 50 episode of “Grey’s” and has also cut Shonda Rhime’s “Scandal.” He’s been an editor on “Grey’s” for seven years and started as a post assistant on “Boston Public” in 2003.

HULLFISH: Thank you so much for doing this with me, Joe. The episode we’re going to spend the most time talking about is “Sound of Silence” which Denzel Washington directed.

MITACEK: That was definitely special. They gave him an interesting episode. It was one that was definitely talked about. I also wanted to discuss this one since it had a lot of what I would call “showier editing.”

HULLFISH: I was amazed at the length of time in this TV episode that there was no dialogue.

MITACEK: Everyone was. “Grey’s Anatomy” is known for having this sort of machine gun dialogue. To have an entire act with almost no dialog ue whatsoever was definitely a bit of a leap of faith on our end.

ue whatsoever was definitely a bit of a leap of faith on our end.

HULLFISH: I liked the episode a lot. Before we get into the specifics, I want to talk through some generalities with you. What was it originally that lead you to editing?

MITACEK: I originally came from Seattle and I moved down here almost 15 years ago. I had a strong interest in film, specifically, how film was made: the people behind it. I didn’t go to film school, but I got my 1st P.A. job with the show “Boston Public.” That was a David E. Kelly series. I met a lot of people that have been in the business for quite a few years and across the board they were really encouraging and they started just throwing movies at me and got me into some foreign films and a lot of books and things to start really understanding the filmmaking process. Having a general office P.A. position was a good thing because I met all these different people in different departments. I thought maybe the camera department would be an interesting way to go, but the more I was reading about the filmmakers that I was interested in, I realized they kept commenting on their editors they worked with and how much they enjoyed the process of editing and how critical an editor was to the process. I thought “I really don’t know how to make a film, but to learn from people like the directors or producers, if you’re in the camera department, you’re competing on set with a hundred other people, but in the editing room it’s just you and the director or even a producer.” I thought, “There’s two advantages to being in editorial: 1) you’re going to learn a hell of a lot, 2) they’re going to know who you are.” You get this time with them and you can forge a relationship. So that was where my interest started to lean towards editing. I also found that, particularly with David E. Kelley, that that company was very post-production friendly, very editorially friendly. They have had a number of producers and directors that had come through post and editorial. I thought that this was definitely a sort of prize department within this particular company. To be quite honest, at the time when I did start getting into post, even as an assistant editor, I still wasn’t really clear as to what an editor truly did. I mean I knew you were putting the show together, in the simplest terms. And you’re following a script, which seems like a guide, but it seemed so incredibly effortless. You’re watching it and it’s logical. It just seems like that’s what you should do. You’re just logically put stuff together and you make the show. That doesn’t seem that hard.

HULLFISH: (laughs)

MITACEK: It wasn’t until I started assisting and spending a lot more time doing it that I really see, “OK, there are actually problems. You get continuity issues and you get maybe a scene that needs to be cut down or you want to intercut some sequences or you’re scoring the show or you’re dropping music in or something. And all of a sudden, I realize, ‘Wow, they do quite a bit of shaping and packaging of an episode.’” You have all these scenes and things and a lot of stuff is going to start being reworked, as you know. And you’re looking for a lot more than just putting the scenes together and making sense of them. It’s like, “Is this scene critical? Do we need this? Can we collapse this into another scene? Does it feel like these beats and moments are happening at the right time? Or do we feel like we need to let some areas breathe a little bit, so it’s not overly frontloaded?” Or you’re hitting a climactic moment at the right time. It’s the sort of satisfying rhythm that a well-constructed movie has or the feeling that it just feels right. Many of these decisions have to be made by the producers instead of the editors. We rely on Shonda Rhimes. She’s tracking the story in a global sense and tonally where she wants it to go. So she is relaying that information to us and we’re making the adjustments. But I’ll ask her questions, “Is this moment important?” or “Is this little beat in between these two characters planting a seed for something coming down stream?” And she may say, “Oh no, this is just a little moment in time for this episode” or “This is a huge thing that’s gonna pay off three episodes from now.” So, being aware of that is important.

HULLFISH: Tell me a little but about the schedule. You said it’s a break-neck pace. What’s the shooting schedule on one of the shows? And then how much time do you get after those shooting days for the director’s cut, the producer’s cut and so on?

MITACEK: The way we’ve been doing things on “Greys” is 24 episodes. Which is not quite as common nowadays. We start somewhere in July and we typically wrap in May. We build up a surplus of episodes before we start airing. Then obviously we’re airing them faster than we can produce them. So at the beginning of the season, we’ve got more time. Typically, we have a 9 day shoot and then, when we get the last bit of dailies, we’ll probably have 2 days to complete an editor’s cut. Then the director comes in for 4 days. Then the producers get 4 days. Then we send the cut to the studio and network and we lock the next day. That’s the schedule at the beginning of the season. Plus we have a certain number of days for sound teams and the composer and all that and then we come to our final mix, lay the show down and get it all out and ready to go. By the time we get to the season finale, that’s truncated to maybe a fifth of that time. Typically with the finale we might end up shooting 10 days. Maybe even 11 days, depending on if it’s an event episode, or if they’re a number of locations, or its just technically more challenging. We might have something like an explosion or a car accident or any number of things that can stretch those shooting dates. But now I am cutting the season finale which had a 10-day shoot ending with final dailies coming on a Friday; turning over the editors cut on Saturday; turning over the director’s cut on Sunday; turning over the Producer’s cut on Monday; and then deliver the show on a Tuesday.

KEVIN MCKIDD (DIRECTOR)

HULLFISH: Holy smokes!

MITACEK: Yeah, so there isn’t a lot of time. We try to get ahead of things by bringing the director up during lunch. When you get into short turnaround then the rules adjust and everything. Anything we can do to get a jump on that stuff. Usually, once I get an episode laid out and assembled, the assistant and I generally watch the episode through and just do what we call a “music spotting” or “music spot” where we talk about, “let’s open with a song” which is sort of conventional, and say, “This is a good point for a cue,” or “Obviously that’s a an act-out so lets put that there” and then say, “Well this can be an interesting sequence for a song, so let’s look for something there.” So we are kinda mapping out where we want the music. So, it’s not just putting a piece of music score in every single scene. We talk about the palette that we might want for an episode but in this case – the finale – everything is just rapid fire. Our last season finale was even shorter: we had the last of dailies, then editor’s cut the next day, then lock the day after that.

HULLFISH: Oh my gosh.

MITACEK: In that case we have in-house directors and producers for the finale, so they know the show.

HULLFISH: At the end of discussing the music you said you were trying to figure out “a palette…”

MITACEK: Depending on the theme of the episode: If it’s an event episode the music might get a little hyper. We might start pulling some feature film scores to temp. For example, we had an episode where the various doctors in the hospital were all working on their clinical trials and it was all sorts of futuristic methods, cutting edge methods, exoskeletons and brain treatments, things that are almost within reach in the medical world so there was a lot of this tech-heavy, technology heavy music. With that episode we had this cool imagery so we built a little opening sequence to the episode with this computer generated imagery we have and put narration underneath it.

HULLFISH: Very cool. Let’s discuss your approach to a scene.

MITACEK: Obviously we’re going to read the script in advance and then we are going to have a read-through with the cast, so, you’re actually hearing it out-loud. The prep time that I have is rather limited. One of the prep meetings that we do have is called a “Tone Meeting” where we go in with the Head of the Writer’s department, the Director, maybe the writer of that episode, and an A.D., the Editor and Post Producer. We talk about logistics and they go scene by scene and talk about, “Okay, Is this beat referring back to something else in the season or tonally is this going to be something where we want the character to be frustrated, but not angry? Maybe just finding a tonal gauge of the scenes. Also, with the medical stuff, everything gets sort of collapsed down. So, babies are born within 30 seconds as opposed to the hours that it would take in real-life. So, we’re blazing through a lot of that stuff. But then, every now and again they’ll say, “Okay, in this surgery we really want to sit in it. We want to sit in the anxiety of it”. Maybe a patient is crashing or something so play the dread, play the waiting, the uncertainty of it. And so, that’s helpful for the director because actors aren’t just slamming their lines up, one against another. So, now they can say a line and just wait and then that also informs the medical team of how they’re going to prepare a scene in terms of the amount of, the medical process. Are we going to do the collapsed down version or we going to actually step all through this? That’s helpful for me because I know when I’m approaching it how I’m going to cut the scene. And it allows us to expand and contract depending on the feel of the episode. As stuff is coming in, I’ll read through the scene, looking for the beats and taking a look the director’s notes just to see if there’s anything specific they wanted in there. Then I start with a master because the masters show me the geography – gives me a sense of where everyone lives in the scene. I’ll just start right after action and end right before cut and I’ll drop that in sort of as my road map. Then I go through the various camera setups for the different takes. Generally what I’m looking for is a particular line reading or I’m looking for a camera move to tag. So, I’m looking for those little things, those little design elements to make sure I’m sorta picking those out and dropping them into the timeline in the appropriate places and obviously looking for performances that I prefer. I am generally going on the theory that if this is a 3 or 4 take performance, that they stopped when they got it, right? So, kind of working my way backwards from take 4 back to 3 back to 2,back to one. Just from being on the show for a number of years, I’ve got a pretty good sense of the actors and knowing the ones that are going to give you almost the same reading take by take and the actors that are going to, if it’s comedic, they might give you a slight variation, each one of them. So, it’s always in your best interest to look through everything and not just assume they got it in take 4. There’s also going to be variation in camera work as well. What I’m looking for are “indicators” because you’re going to get little variations from performance. One of the things I found to be sort of a handy trick is whenever they do any pickups is that they shot the pickup for a reason, so that can be a great indicator in terms of the emotion.

DEBBIE ALLEN (DIRECTOR)

HULLFISH: Because that moment was so specific, right? Great tip. I’ve got a quick question while we’re kind of on the subject of coverage. In “The Sound of Silence” episode, there was a Steadicam or jib or something around the car, just before they came up on the accident. Talk to me a little about those special shots.

MITACEK: We have one producer/director in house who gives you quite a few options which is always great because you never know if the scene has to collapse down or you might need to enter the scene in a different way. But something like that, the shot you’re noting specifically was very clearly the way to begin the episode. That was always meant to be the opening shot by design, no question. You could theoretically start in the car and then pop out and see the other things but it made the most sense for transitioning from a sort of abstract beginning where Meredith is giving her narration and then we’re flying down and finding them. Also there’s a moment where Maggie points out and says “look at that bee right there, that bee” and I kept joking well it sort of feels like a flight path of a bee the way it’s coming and finding them and so we said,”Well, there should be a bee in there. I mean, she’s pointing at the bee. So, what we did was we found a moment to digitally insert a bee that actually comes up as the camera is kinda flying in there. It sort of zooms into frame and it just flies out. I thought it was a kind of nice little touch. It’s very quick and subtle but it’s there.

HULLFISH: How often are you long? What do you do to get an episode to time? It’s not like a feature film where you can be however long the story “wants” to be…

MITACEK: It depends, if we have an episode that’s two minutes over then we’re probably going to tighten it down and I’ll do a few line lifts and that’s that. Little surgical line lifts tend to be invisible. The deeper cuts get tricky, like when you’re cutting 10, 12,15 minutes – which doesn’t happen all that often – but when it does you can sort of surgically trim lines here and there but then you actually get into deeper cuts where you’re ripping a section out of the scene and now we have to figure out a way to glue it together.

HULLFISH: Talk to me a little bit about collaborating with these directors because for those that don’t know: the director on a TV show is not like the director on a film where he’s the end-all and be-all, right? It’s the show runner that is the end-all and be-all. So, you’re dealing with these directors and you probably know the show better than the director.

MITACEK: Generally, if it’s someone I haven’t worked with before, I’m going to meet them in the tone meeting or the read-through. I’ll go and introduce myself. I might pop up during prep at some point, to say hello. Just to start a dialogue. I’m not going to kind of force an idea on anyone. I usually like to pop down periodically and let him know that everything’s looking good. It’s really putting them at ease letting him know everything is okay. If I’m concerned about something or I feel something’s been missed, I might go down and just ask them, “Did you have an idea for this section?” and they might say “We’re planning on getting that close up when we revisit the storyline later in this shooting schedule.” – just clarifying what their plan is in a way that’s not alarmist. And as we get closer, I might let him know, you know, it looks like we’re going to be 5 minutes over. They’d say, “Is that normal?” I’d say, “Yeah that’s about right.” I would say for the most part directors come in saying, “You guys know the show better than anyone, so, if I’m off course, help steer me back”. When we watch the editor’s cut I’m thinking, “Okay, here are some things I want to address” and that starts the dialogue. So, I might say, “Well, you know this storyline for Meredith- it’s not just quite feeling like it shaped out. I think we need to help some earlier beats to make it so we really have a pay off here.” Or maybe, just saying, “I feel like maybe this B-storyline just gets a little bit pushed to the side, so maybe we need to play the music a little more, give a little bit more emphasis to add a little weight to it.” So it’s that kind of stuff. Shonda generally likes to have the entire episode as scripted laid out. So, what I suggest to the directors is “Let’s not cut stuff. We’ll just make our list of things we can cut and then, when the time is appropriate I can pitch some ideas to her to cut. It’s definitely a collaborative thing and they have to come in and rely on the A.D. who’s going to help them navigate. When notes come back from Shonda, I’m quick to let them know, “Don’t worry that’s editorial stuff. That does not concern you. She’s happy with the episode, she likes what you shot, and this is just my stuff.”

HULLFISH: Talk to me a little about pacing and rhythm, the speed of a scene and how do you find it.

MITACEK: Often Shonda is pitching a bunch of lifts and she’ll say take the ones you like, ignore the ones you don’t like. When we line the whole episode up that’s when we do these uniform passes through of tightening. I want to be careful that I don’t over-tighten the front end of the show and leave the back end of the show feeling really loose and languid

HULLFISH: Let’s talk a little bit about the episode specifically that you sent me. It seemed like a lot of things were done to give you Meredith’s perspective.

MITACEK: Yeah.

HULLFISH: How did you accomplish that?

MITACEK: That was scripted. We rode the line between literal point of view and perspective. To do that, I used a few techniques or tools.

HULLFISH: What were those?

MITACEK: I requested GenArts’ Sapphire effects package because I want to add a shallow depth of field feeling. Also we used close-ups of Meredith after the attack with an effect of her eyes blinking. We had a little matte created. What dialogue leads the edits? When someone says something to Meredith and she throws a look at them, we want to see what she’s looking at. One of the things that was instilled in me early on was never cut on a blink, because it disrupts the connection you have through the character’s eyes, especially in a show like “Grey’s Anatomy” where it’s emotionally driven. So, the connection between the eyes is an incredibly important part. It also just makes for cleaner edits. But with this episode, the blinks are actually a great way to get into her POV, so I’m actually looking for places where she does blink and as her eyes go down or they’re starting to open then I flipped to her point of view and I’m using the flicker effect there. I feel that worked really well. Plus if I need to speed something up or I want to go from one performance of the same shot to another I can mask it with a blink and what I was also doing is: on the A side, cut 2 frames of black, 2 frames of the next picture, 2 frames of black, and then going to the next picture. I can’t remember the rhythm exactly but I’d also do a resize in the middle of the blink, almost the way that there’s that momentary recalibration of your eyes that occurs, because I didn’t want it just to be a literal camera perspective. Another thing, on the POVs we created a darker vignette and softened the edges with a blur effect around the periphery of it. So that helped focus the POV and also just give the illusion of it being seen through someone’s eyes. Anything to sort of create that closed in feeling.

KEVIN MCKIDD (DIRECTOR)

HULLFISH: It was also her only way to communicate.

MITACEK: I calling it a “cocoon.” When Meredith is in Act 3 in her recovery state, it’s like this soft focus that’s only sharpest focus right across her eyes to give this claustrophobic feeling that really isolated her. We’re getting the vibe of where she’s at, where she’s in her drug haze. And then, as that act moves along we slowly start to recede and pull those back. So, they’re not as quite as pronounced. And then as the act unfolds, I started placing a piece here, a piece there, where we’re not always with her. Like we’re starting to roll out of it. We finally get to the scene where Alex comes in with that ear piercing tinnitus sound where the dialogue and backgrounds are muffled and Alex comes in and her hearing starts to return. So, it was a way to just start out completely in her perspective and POV at the beginning and let it sort of subtly unfold. It took a bit of crafting but that was a lot of fun.

JAMES PICKENS JR., ELLEN POMPEO

HULLFISH: Absolutely. Talk to me a little bit about the scene where Richard is telling her she needs to forgive. I can see you’ve done some split screens that they must have cleaned up in on-line or VFX to make two separate performances into a single wide shot. Or maybe it’s the same performance but you re-timed each side of the shot. Talk to me a little bit about using those splits to be able to craft performances.

MITACEK: So, there was a longer version of this scene. Originally we came off a tree and found Richard pushing Meredith in the wheelchair and he was still singing and they parked and sat down on the bench and kind of had their little moment and there’s some small talk before they got into the meat of the conversation. This is one scene, if I had my way, that would be longer but you’ve got to cut off a finger at some point. This initial split screen here, I had to jump into things because I need to cut some time and by collapsing it down, I needed to be able to control these beats quite a bit more where Meredith’s mental state is changing in the longer version over time.

HULLFISH: Right, because the stuff you cut out gave them time to get from one emotional place to another and now that you don’t have that, you still need the emotions to be able to change.

JAMES PICKENS JR., ELLEN POMPEO

MITACEK: Yes. This was a tricky scene because shortening it caused this sort of ripple effect because we had to lose some raking shots that connected the actors in the same shot and without the raking shots, they’re not connecting any more. Yeah, this took a little trickery. I had to blow some shots up and do some split screens and to be quite honest with you, sometimes you get performance stuff that needs a little help.

HULLFISH: But the performance is not the actor’s fault, right? It was because when you cut out 4 lines or something, the actor doesn’t have a chance to get emotionally from point A to point B.

MITACEK: That’s definitely something that we’re up against with this scene. So most of these split screens were at the top of the scene because I needed to shape where we wanted Meredith’s mental state to be, in this moment. There are times when I had to manufacture her getting from point A to point B. Split screens we’re really helpful there because I could take an earlier part of Ellen’s performance and pair it with what Richard was saying, in a later moment. I could say, “Well, I don’t want her to be so far along in her arc.”

HULLFISH: Right, because the scene before this is her being pretty angry and upset that he’s kind of kidnapping her. And he’s trying to get her to a different place, this place of forgiveness and kind of softening a bit. And by cutting out scenes, you lose that arc where she was trying to act from A to B.

MITACEK: Also, with the sound design I knew we needed to hear kids laughing, birds chirping, we need life. We want to feel a complete aural shift when we go outside from the cold clinical feel. That’s Richard’s point in taking her out there: get her outside the place that she has been trapped and enjoy the beauty. I want to give them that beat where they’re sitting there and Richard had some transitional time to get from one emotion to another. Ellen was still sort of lost – ignoring him, kinda in her own thoughts. But since we lopped off the top of the scene, we lose that time for her to start coming out of her shell. That was a tricky one.

HULLFISH: Talk to me about setting up the opening attack at the beginning of the episode.

MITACEK: There’s a few things that I thought were really nice when Meredith was touching his face and I felt like, she’s really taking her time with the patient – she crosses his arms and she is sorta gentle with him. Like, she give him a little pat.

HULLFISH: She wipes his face….

MITACEK: It’s just those little touches that affect downstream and makes it even more sickening and heartbreaking that she was careful and caring for this guy which makes it even more just shocking when the attack happens. I think it was really interesting blocking having her back turned to him at the beginning of the attack and a shot of his hand beginning to move. There are little horror elements sprinkled in this scene.

HULLFISH: That’s what I thought.

MARTIN HENDERSON, ELLEN POMPEO, JESSE WILLIAMS, JUSTIN CHAMBERS

MITACEK: We have a little ambulance siren in the distance that might start to wake him up a little bit. The actor gives us a great performance the way he kind of looks around trying to figure out where he is and almost rolls a little bit off the bed and when I was going through the dailies, I just saw that shot where we’re behind the bed and we see the back of Mer’s head and he rose up and the moment I saw that, I thought, “Oh, that’s the shot right there!” It’s just so ominous. Because we don’t necessarily know where this is headed, but it’s not feeling right. It’s like the monster in the background.

HULLFISH: When you’re watching dailies, are you writing notes on a pad? Are you putting locators in? How are your scenes organized and laid out by your assistant? Are you using frame view? I’m assuming you’re on Avid. Talk to us a little bit about that.

MITACEK: Yes, We are on Avid and we are doing frame view. Visually you can identify immediately what the set up is.

HULLFISH: How do they lay out your scene bin for you? Do you like your wide shots at the top and then coverage or just whatever order that they’re shot?

MITACEK: In the upper left-hand corner, I have take 1, 2, and 3 of the master on one row so it would be right next to each other. And then step down from that, you would have the A set up and that’s usually like an A/B cam, so, then it’s kinda like a little pyramid, a little triangle. So, they’ll have A on the left and B on the right. And then sitting around on top of those like slightly above it, to form a little pyramid, that would be the group shot and that’s the one that I use to cut. And so that would be, you know, take 1, 2, and 3. And then, the B set up and then maybe C and D are just insert shots or something. I like it typically to be starting with the master in terms of setups. But sometimes what might happen is, if, in the middle of the scene they change blocking and they move to the other side of the room, so that the master shows all of that but then A setup shows the first half of the scene then the B setup shows Meredith on the other end of the scene of when she crosses the room and ends up somewhere else. I’ll have them lay those out almost as separate scenes. I might adjust those around, so that, the bin would start upper left: first the Master, then it would be Meredith’s coverage for the first half, then Richard’s coverage for the first half, then Meredith’s coverage for the second half and then Richard. So it’s kind of paired up against each other. Just little ways to keep things organized. It just brings a little bit of logic and order to the way that I am approaching it. Sometimes with a big scene, it’s got a lot of little sub scenes within it. Then, I may just look at it, like, I just want a, let’s work on the 1st little scene, the little sub scene, in there. And treat that as its own separate little scene. And then work on the other one and then work another one, another one, another one. Then try to find the sort of connective tissue to get to those places.

HULLFISH: When you’re looking at dailies, are you just always editing? Or sometimes do you just watch and making mental notes? Are you putting locators in? Are you writing stuff down?

MITACEK: It’s a combination of those, I mean often times, I just dive right in and that’s because I’m just comfortable with the show. With certain actors, I can just look at the bin and I already know essentially what we’re gonna get.

HULLFISH: (Laughs) Oh, wow.

MITACEK: You don’t have time to make a meal out of every scene so if it’s just two people walking up to a nurse’s station, that’s just a scene where we just try to hit a story beat and move on. There’s only so much time in the day. In other scenes I’m looking for the most interesting little flecks of footage that may have been something with the cameras adjusting but it’s just did a cool little rack, really quickly. And I think, “I could just use that little piece there somewhere,” so, I’m just kind of filing those away.

HULLFISH: Kinetic little moments.

MITACEK: Yeah, kinetic moments. That’s a great term for it. There’re enough little abstract moments in there. There’s an interesting thing with the scene of Meredith first being worked on after the attack. Shonda pointed out to me “the rhythm of this scene – it’s breakneck and it goes breakneck all the way through” That’s the way I initially played it. I was just like badam, badam, badam, badam, badam, it was one thing after another, after another and she said, “Switch gears. Find moments where you can accelerate it and moments where you can kind of fall back.” Initially I just did quicker cuts to kinda get through. That was kind of a lesson that you can really sorta ride the gears a little bit. You can ramp it and then slow it down then hit the brakes and then fire back in again

HULLFISH: It’s a very musical way to think about it. Tension and release of tension.

ELLEN POMPEO

MITACEK: With a scene like this, I just can’t dive into it. I need to see it all. Tag stuff that I like. Review the script a few times and bake on it overnight.

HULLFISH: That’s a great idea. Whenever I can, I like to view dailies and have a night to let it gel in my mind.

MITACEK: Yeah. Catalog it all and then walk away from it or maybe string some stuff out. And I always go, “Oh God I have no idea what I’m going to do with this, this is never going to work.” But I walk away from it and start thinking… then music starts creeping into your mind… all of a sudden you have a trajectory and then you take off.

HULLFISH: Great advice. Thanks so much for talking with us today.

MITACEK: You’re welcome. I’m honored to be a part of the series. You dive much deeper into the craft than anybody else.

To read more interviews in this series, or to find out about future interviews, check out THIS LINK or follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish. And please join in on the conversation below! What should I have asked? Who else should I interview? Do you have points of agreement or disagreement with Joe or me? Post your comments below.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now