Job ter Burg, is a member of both ACE (American Cinema Editors) and NCE (Netherlands association of Cinema Editors) and has nearly 80 editing credits. His last film, with acclaimed director Paul Verhoeven, received a fantastic critical reception at Cannes and was picked up for distribution in the US by Sony Classics.

He also edited “Brimstone” which has received great acclaim after its debut at the Venice Film Festival and is much anticipated at the Toronto Film Festival.

Watch for “ELLE” in the US later this year and “Brimstone” next year.

HULLFISH: You and I have known each other for many, many years, but tell us some the films you’ve worked on and how you got into film editing.

TER BURG: When I was around 20 years old I decided I wanted to be a film editor. I took this video course while I was studying Theatre, Film and Television Studies in University and they told me about video editing. Before that I had been doing music editing (on quarter inch tape) and DJ-ing and I had created radio plays as a teenager. I acted in school plays in high school and I really liked that. And then I saw editing, it was a revelation to me because it combined everything I love: acting and sound and picture, all together. So I managed to get into film school in Amsterdam, where I majored in film editing. Some friends of mine had set up an editing facility in Amsterdam (Phanta Vision), and after I had graduated they offered me a job as an editor on a series of television documentaries for a large public broadcaster. I worked there for a couple of years, and loved doing documentaries. In the meantime, a buddy of mine from film school, Martin Koolhoven (director of “WINTER IN WARTIME” and “BRIMSTONE”) got a few chances to direct: some music videos, a single play, a television feature, and then two theatrical features, and he was able to bring me on board to cut those. And another buddy I had met when I was still in University, Pieter Kuijpers, got a chance to direct his first feature film (“GODFORSAKEN”), which was also quite successful. So I got lucky pretty early on to be connected to some people that helped me get some nice projects that were received rather well.

HULLFISH: How did you and Paul Verhoeven get to work together?

TER BURG: Paul had been working and living in the US for many years, but was doing “BLACK BOOK” in Europe. It was being produced by San Fu Maltha, whom I had known for a few years. It was a large co-production, shot by German cinematographer Karl Walther Lindenlaub (“UNIVERSAL SOLDIER”) and they worked with a British editor. At some point, however, they had a falling out with that editor. San Fu then proposed to Paul to ask a few Dutch editors to cut a scene, so they could see if they could pull it off or not. When they asked me to cut a scene, I didn’t even think I was ever going to get the job, I just felt it would be a great opportunity to work with that footage. But it turned out they really liked what I had done, and they hired me to cut the film. I was on that film with Paul for 7-8 months or so, in Amsterdam, and we had James Herbert (now mostly known for his collaborations with Guy Ritchie) working with us from London for the first 10 weeks, so we could get up to speed (obviously some time had been lost when changing editors).

Paul and I got along very well and we became pals. After “BLACK BOOK” he was involved in several other projects that he wanted me to cut, but unfortunately all of those fell through for a variety of reasons.

We teamed up again in 2012 for “TRICKED,” which was a 50 minute film based on a crowd-sourced script. And then in 2014, French producer Saïd Ben Saïd (“CARNAGE,” “MAPS TO THE STARS”) asked Paul to direct “ELLE,” and Paul brought me on board.

HULLFISH: “Elle” is a French film, so did you collaborate in French or in Dutch or English?

TER BURG: When it’s just the two of us working, we speak Dutch. But since this was a French film, in pre-production, Paul felt he needed to direct in French. He did already speak the language, but he took this intensive one-week immersion course so he would be confident enough on set. For me, while I understand French rather well, it was harder to speak it, as I had not really practiced it since high school. And especially if you need to convey complex ideas (which of course happens all the time when you’re editing a film), you can quickly feel limited. So most of the time, I spoke English with the team. I could follow their French conversations very well, but responded in English, so it became a mix of languages. By the time we were in final mix, I managed to communicate in French 85% of the time. If I would’ve stuck around for another month my French would have probably been great – but I had to go back to Amsterdam to cut another film.

TER BURG: When it’s just the two of us working, we speak Dutch. But since this was a French film, in pre-production, Paul felt he needed to direct in French. He did already speak the language, but he took this intensive one-week immersion course so he would be confident enough on set. For me, while I understand French rather well, it was harder to speak it, as I had not really practiced it since high school. And especially if you need to convey complex ideas (which of course happens all the time when you’re editing a film), you can quickly feel limited. So most of the time, I spoke English with the team. I could follow their French conversations very well, but responded in English, so it became a mix of languages. By the time we were in final mix, I managed to communicate in French 85% of the time. If I would’ve stuck around for another month my French would have probably been great – but I had to go back to Amsterdam to cut another film.

HULLFISH: I cut a project in Spanish once and it was not a language I speak very well but I can understand a little. I would think language would be a challenge in a film like this. Did you feel like your language skills made it difficult to cut dialogue or was that pretty easy?

TER BURG: I had figured I would be okay but when I was watching the first dailies, I did get a little nervous when I did not understand a few lines in that scene. Until I looked at the reports from our script supervisor, and noticed she had written ‘He’s mumbling, we don’t really get what he is saying.’ From that point on I felt I could just trust my own ears.

Also, it’s not always that important for an editor to understand the exact words of a line. I mean, I’ve cut documentaries in Japanese and Shanghai Chinese, and have had films with scenes in Arabic. Even if you don’t get it word by word, you still get a feeling for the performance, and that’s what’s most important.

HULLFISH: I don’t know too much of Verhoeven’s total body of work. Is this a different type of film for him?

HULLFISH: I don’t know too much of Verhoeven’s total body of work. Is this a different type of film for him?

TER BURG: I would argue both ways, it’s very much a Verhoeven film. There are themes in this film that he is very familiar with. At the same time, it’s also different from his other films. “TRICKED,” was the first time he shot digitally, with two Alexa cameras, handheld. He really liked that because it gave him a certain freedom to move around. It felt similar “TURKISH DELIGHT,” with Jan De Bont as his cinematographer. In a way he reinvented himself, after having done complex, effects-heavy films where he did not have that type of freedom to move around as much. “ELLE” was shot with two Red cameras. Our DP, Stéphane Fontaine (“A PROPHET”), preferred those because they are so light. And of course, one of the things that Paul is really great at is staging. He really knows how to stage a scene and especially with hand held cameras. He always makes sure that there’s a lot of interesting dynamics.

HULLFISH: Now does that make the editing more challenging or easier?

TER BURG: With two cameras you get more footage and more options. Paul tends to make sure there’s enough coverage, so there was quite a lot of footage to digest. But I don’t mind choosing from a lot of good stuff, which is what he provides me with. It would be way worse to have tons of footage that doesn’t make any sense. But finding the very best in a whole lot of great footage is something I really like.

HULLFISH: Talk to me about project organization. How do your assistants prepare and organize the film? Project organization, bin organization?

TER BURG: I think I have a rather traditional way of organizing, with daily bins for picture, sound and synced clips, plus folders with bins per scene, that I work from. I like to create a sequence with all the footage for a scene, then review that, adding markers where I want to make a note, or sometimes I’ll add notes to the script reports. It’s important to ‘record’ your first impressions somehow. And sometimes, many weeks later, you can go back to that sequence and quickly browse through it to check there’s nothing missing that you originally liked. I’ll usually assemble the scene from that sequence as well, and keep the first cut of each scene in its scene bin, and then create a cutting copy sequence from those cut scenes. I’m also a huge fan of Avid’s script-based editing and ScriptSync, especially on more complex dialogue scenes. There’s a pivotal Christmas sequence in “ELLE,” where nearly all character in the film are present, which I think ran for 12 pages. It was broken up into various scenes in various corners of the house, but especially the dinner scene was quite complex. Having all the footage for that scene in a script in Media Composer gave me the best overview, and instant access to any on-screen or off-screen reading of any line. I’m a fan of that technique, I’ve used it on many films and I’m really disappointed that Avid hasn’t been able to make a deal on licensing it again with Nexidia for v8. It’s why I cut this film on v7.

TER BURG: I think I have a rather traditional way of organizing, with daily bins for picture, sound and synced clips, plus folders with bins per scene, that I work from. I like to create a sequence with all the footage for a scene, then review that, adding markers where I want to make a note, or sometimes I’ll add notes to the script reports. It’s important to ‘record’ your first impressions somehow. And sometimes, many weeks later, you can go back to that sequence and quickly browse through it to check there’s nothing missing that you originally liked. I’ll usually assemble the scene from that sequence as well, and keep the first cut of each scene in its scene bin, and then create a cutting copy sequence from those cut scenes. I’m also a huge fan of Avid’s script-based editing and ScriptSync, especially on more complex dialogue scenes. There’s a pivotal Christmas sequence in “ELLE,” where nearly all character in the film are present, which I think ran for 12 pages. It was broken up into various scenes in various corners of the house, but especially the dinner scene was quite complex. Having all the footage for that scene in a script in Media Composer gave me the best overview, and instant access to any on-screen or off-screen reading of any line. I’m a fan of that technique, I’ve used it on many films and I’m really disappointed that Avid hasn’t been able to make a deal on licensing it again with Nexidia for v8. It’s why I cut this film on v7.

HULLFISH: I am working a documentary right now and basically because we are on Nexis, I am cutting everything on version 8.5 but I’ve got version 7 of Symphony that sits on the Nexis and is just used to for PhraseFind (which uses the same technology.)

TER BURG: That works for now and that’s how I am going to do it on whatever the next project is. The thing is: at some point it’s not going to work anymore because of incompatibilities. For example, 2K 2.39:1 DNxHR footage from the current version of Media Composer can’t be ScriptSynced in v7.

HULLFISH: No, I completely understand. I’m not happy about it, as are many people. A lot of people don’t even use ScriptSync using the “true ScriptSync.” They’re really using what Avid calls Script Integration where you manually sync up the lines, but it’s a LOT more time intensive.

HULLFISH: No, I completely understand. I’m not happy about it, as are many people. A lot of people don’t even use ScriptSync using the “true ScriptSync.” They’re really using what Avid calls Script Integration where you manually sync up the lines, but it’s a LOT more time intensive.

TER BURG: Right, it just takes a lot more time. It’s also a shame, even without ScriptSync in the mix, that they haven’t developed Script-Based Editing in over a decade. I am pretty pissed off that they haven’t even bothered to give us 16:9 thumbnails.

HULLFISH: When I cut “War Room” I was not happy about that! Man, it looks like you’re back in 1980 again. It’s such a great product. They could at least make it useable.

TER BURG: Yeah, I don’t really think there’s anyone at Avid anymore that truly gets the power of this feature. How hard would it be to add some word processing capabilities to the scripts, to make it easier to put in the improv? It’s very easy to see how you want it to work. You and I could probably work the ideas out in one afternoon.

HULLFISH: (laughs) Let’s do it! I know all the things that are wrong with ScriptSync. Switching gears: What’s your process of watching dailies? Do you watch in a theater? On your system?

TER BURG: I watch dailies on the editing system. I would love to watch them in a screening room but on the productions I have worked so far, there was no time and money for that. I usually work with a large plasma monitor so I don’t watch it on too small a screen.

Before I start working on a scene, I like to watch all takes. Sometimes, if we have tremendous amount of angles or something, I might go to the last two or three takes first to find the way I think the scene needs to be constructed, and then I’ll go through the takes as I am working on it.

I sometimes wish I had one approach that I knew would always work, but I always end up using different approaches – whatever helps me process the footage for that particular scene. Honestly, a lot of times you are just wondering: how the hell am I going to start this? And often you have to just re-watch the whole thing to find the one moment that speaks to you to get you started. But that process does involve walking around in circles in my room, trying to decide what is the best way to approach it…

HULLFISH: I have an oval worn into the carpet of my room.

HULLFISH: I have an oval worn into the carpet of my room.

TER BURG: I think all of us do, right?

HULLFISH: Do you stand or are you sitting?

TER BURG: I am mostly sitting. I do have a second setup in the room which is on an electronic riser so I can stand or sit on the 2nd station. I sometimes stand but not during the actual editing; maybe I’m just too lazy. I do like standing when I am doing technical stuff.

HULLFISH: I’ve switched very much to standing which is one of the reasons I’ve found myself pacing so much because it’s easier to go from a standing position to walking than when I am sitting. I really like standing. When I am doing organizational stuff or a lot of tech stuff, I sit but when I am editing, I love standing.

TER BURG: A lot of people do and I guest-teach some classes in film school as well and fortunately, they got all these desks that are fully adjustable for sitting or standing. So some of them are actually doing that as well, standing up; I know some colleagues that do it and somehow, maybe I am just too lazy. I should consider doing that.

HULLFISH: So we talked a little bit about your basic approach but I wanna kind of get on that some more.

TER BURG: I usually start with a rough assembly, without any fine cutting. For dialogue scenes it will often be a line-by-line cut of the performances I like best. I’ll sometimes scroll through that assembly a few times or play it at double speed to check if the ‘grammar’ of the scene is starting to make sense. Once I get a feel for that, I’ll dive into the actual fine cutting, and these days, I tend to either mute the audio or play it back so softly that I can hear the actors speak, but I won’t be distracted by anything in the production sound track. Otherwise, sounds that are not supposed to be there (and that will absolutely be gone when you’re in final mix) can easily mess with your sense of rhythm. When I feel I have something that at least has a proper visual pace, I start working on the sound quite a bit. I’ll add some room atmospheres and sound effects, even before opening up the production sound and dialogue. If the scene is really noisy, I’ll try and clean it up, manually, or with something like iZotope RX if needed. I tend to go further and further in how much I treat the sound already because I really like to watch a scene with the sound as good as I can possibly get it. And that helps for screenings too, of course. So there’ll often be a low-cut EQ filter and a mild compressor on the RTAS inserts of my dialogue tracks, in order to smooth them out. I mean, it’s not a perfect mix but it’s a pretty nice way to get things balanced and together so that it’s easier to watch the scene without being distracted by the sound.

HULLFISH: I think that’s true for a lot of people too.

HULLFISH: I think that’s true for a lot of people too.

TER BURG: Yeah, I think I am kind of anal about it. I find it so hard to watch a scene with raw sound. It’s going to be so jarring if you hear any sound cut or if things are unbalanced or one person is speaking too loud or whatever. I have my audio monitoring in my room calibrated, so I can always work at a standard level. It enables me to take my cuts to a screening room at any point in time without having to do a mix pass – or having to reach for the volume knob all the time.

And I cut in 5.1 – or mostly LCR (left-center-right), but sometimes I can’t help myself and play with the surrounds a bit. I prefer to have a center speaker, it helps ‘tying’ the sound to the screen, especially for dialogue of course. And it’s the way things will sound when played back in a screening room, so working with just a left and right speaker doesn’t cut it.

HULLFISH: Wow, that’s very interesting. I love all that detail. So you go through, you cut all these individual scenes and you like the pacing of them. Then you kind of bring it all together into a first pass of the movie and what are some the structuring or macro-pacing issues? Like a scene you feel pretty good about, then when you put it into a whole movie, now your sense of the pacing changes, right? Tell me a little about that.

TER BURG: That’s actually the longest part of the process, going back and forth between macro and micro. What I used to do in the past, what I still see some people do is they will have gone through each scene, then assemble the scenes in script order, everything is there and every scene has been worked on and they go to the beginning of the sequence and they press play and they watch the whole thing. I stopped doing that quite some time ago because I found it only depressed me and the director.

HULLFISH: (laughing) You’re not the only one!

TER BURG: Because after 12 minutes, you’ve seen tons of things that don’t work, or things you want to change or try, and you still have to watch another 2 hours of scenes that are in a similar shape. So, to me at least, it makes much more sense to approach the film in sequences. So you start working on the first 10-20 minutes of the film or so, and focus on that. Then you try to make longer and longer passes until you start to feel somewhat confident about the sequences. And only then do you watch not just a rough assembly, but at that point the real first proper cut of the film. Then you get into the process of working with the director, trying to find the best and the weakest parts of the film: where does it play and where does it not yet play well: where it’s either unclear or too clear, not dense enough or too dense. This was actually the first film that I used picture cards on. I picked up from a buddy, Peter Alderliesten, who will print a picture of a key frame for every scene in the film, with the scene number, and some magnetic adhesive tape on the back, and then puts them up on these huge whiteboards. On this film, we didn’t shuffle too many scenes around (we really couldn’t, plot-wise), but it still gave us a better overview of the film. At some point we had a cut of the film and we felt it was something like 15 minutes too long. It wasn’t a matter of a scene or sequence, but just that the entire film felt too long. We didn’t immediately know where to start, but had some ideas. So we went back and forth between the whiteboards and the timeline, and tried various ideas, and made the film shorter. A few days later, we were preparing for a screening and Paul said: “What have we taken out over the last few days? Let’s put all of it back in for the screening and watch them one more time.” At first I felt we were taking steps backwards, but he argued that we already knew we could take them out, and how to take them out. He wanted to give those scenes one more chance to make it into the movie. And he was right, we ended up putting some of those scenes back and taking out others. That also had to do with the fact that this film is more character-driven than plot-driven. So it was mostly a matter of deciding how much time we would dedicate to either this particular character or that relationship between characters.

TER BURG: Because after 12 minutes, you’ve seen tons of things that don’t work, or things you want to change or try, and you still have to watch another 2 hours of scenes that are in a similar shape. So, to me at least, it makes much more sense to approach the film in sequences. So you start working on the first 10-20 minutes of the film or so, and focus on that. Then you try to make longer and longer passes until you start to feel somewhat confident about the sequences. And only then do you watch not just a rough assembly, but at that point the real first proper cut of the film. Then you get into the process of working with the director, trying to find the best and the weakest parts of the film: where does it play and where does it not yet play well: where it’s either unclear or too clear, not dense enough or too dense. This was actually the first film that I used picture cards on. I picked up from a buddy, Peter Alderliesten, who will print a picture of a key frame for every scene in the film, with the scene number, and some magnetic adhesive tape on the back, and then puts them up on these huge whiteboards. On this film, we didn’t shuffle too many scenes around (we really couldn’t, plot-wise), but it still gave us a better overview of the film. At some point we had a cut of the film and we felt it was something like 15 minutes too long. It wasn’t a matter of a scene or sequence, but just that the entire film felt too long. We didn’t immediately know where to start, but had some ideas. So we went back and forth between the whiteboards and the timeline, and tried various ideas, and made the film shorter. A few days later, we were preparing for a screening and Paul said: “What have we taken out over the last few days? Let’s put all of it back in for the screening and watch them one more time.” At first I felt we were taking steps backwards, but he argued that we already knew we could take them out, and how to take them out. He wanted to give those scenes one more chance to make it into the movie. And he was right, we ended up putting some of those scenes back and taking out others. That also had to do with the fact that this film is more character-driven than plot-driven. So it was mostly a matter of deciding how much time we would dedicate to either this particular character or that relationship between characters.

I would also like to say how involved our producer, Saïd Ben Saïd was in the process. He regularly came to Amsterdam to watch and discuss the film, and I would often send him Vimeo links. He was a valuable sparring partner for us and we had a great time. I’m not saying it was easy, because no film is ever easy to do – but it was a very pleasant and constructive collaboration between Paul and Saïd and myself.

HULLFISH: How long was that first cut?

HULLFISH: How long was that first cut?

TER BURG: That was around 150 minutes.

HULLFISH: And what was the final film?

TER BURG: 128 minutes, not counting end credits.

HULLFISH: That’s not too bad. 22 minutes… a lot of movies require worse chopping than that.

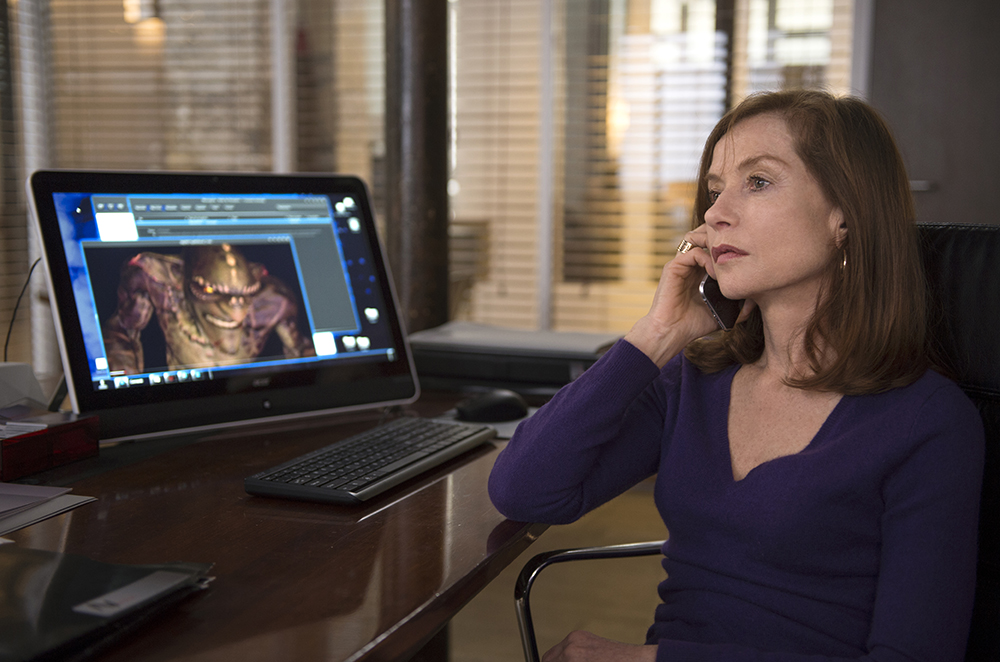

TER BURG: We didn’t cut out too much. David Birke’s script proved to be pretty tight. The largest section we took out was what we called the ‘New Year’s Eve’ scene. That was a scene we tried to cut in many different ways, we kept tweaking it, trying to tighten it, but we kept feeling the scene was getting in the way. That’s probably the biggest section we took out. Plus a scene near the end of the film where the main character, Michele, played by the wonderful Isabelle Huppert was browsing through pictures from her childhood, just before burning those pictures in the garden. And there were of course a gazillion small tweaks to tighten scenes or dialogue, as you do.

HULLFISH: What about music? What do you temp with? How do you like to deal with temp? Does Verhoeven even like using temp?

TER BURG: We did use temp music. I have to say, over the last few years, I’ve been trying to use less and less temp score when I am working on my cuts of the scene. I used to do that more but I somehow started getting annoyed with using too much music too soon. Music can be deceiving. It can easily mask sections that are not well-paced in and of themselves. Then again, in the past I’ve also sometimes used a piece of music just to have a rhythmical guide when cutting a scene, only to throw it out once I found the right pace for the scene.

On “ELLE,” it was quite hard to find temp score that would fit the film. There was not a lot of music we found that would actually ‘stick’ to the film. I think it has to do with the ambiguity that is in this film and its characters. As soon as you put music to that, the duality is lost and it becomes..…

HULLFISH: …either one thing or the other, but not both, which is the art.

TER BURG: …or it gives a certain color to a scene that may just kill the very ambiguity that we loved so much. So it took way more time than usual to find the right temp music. Eventually we did find some cues that were in the right direction and then Paul started to work with composer Anne Dudley (“AMERICAN HISTORY X”), who had also scored “BLACK BOOK.” Anne gave Paul a CD with her score for “POLDARK,” a British TV series. We found two cues from that score that struck the right tone. So we used temp, and we sent most of that to Anne, and we tried to convey to her why we thought a certain piece of music was working, what we liked about it, and what we didn’t like about it… what we felt the cue had to contribute. And she picked up on that really well. She never tried to copy the temp. She tried to understand what the temp brought to the scene and then did her own thing to achieve that. Of course you gain a lot of coherence in the actual score, because the composer can create all kinds of thematic links throughout the film – something that is very hard to achieve with temp.

TER BURG: …or it gives a certain color to a scene that may just kill the very ambiguity that we loved so much. So it took way more time than usual to find the right temp music. Eventually we did find some cues that were in the right direction and then Paul started to work with composer Anne Dudley (“AMERICAN HISTORY X”), who had also scored “BLACK BOOK.” Anne gave Paul a CD with her score for “POLDARK,” a British TV series. We found two cues from that score that struck the right tone. So we used temp, and we sent most of that to Anne, and we tried to convey to her why we thought a certain piece of music was working, what we liked about it, and what we didn’t like about it… what we felt the cue had to contribute. And she picked up on that really well. She never tried to copy the temp. She tried to understand what the temp brought to the scene and then did her own thing to achieve that. Of course you gain a lot of coherence in the actual score, because the composer can create all kinds of thematic links throughout the film – something that is very hard to achieve with temp.

HULLFISH: Talk to me a little about how you shaped or molded an actor’s performance with editing. What’s your take on performance and the editor’s role in crafting it.

TER BURG: Well, it depends it on the movie, it depends on the scene, it depends on the actor, it depends on the director. There are various types of actors. Some actors will only do subtle variations, and others may give you nine or more completely different varieties of a performance – and you have to select from those, based on what you feel the scene or the character’s arc requires. Isabelle Huppert was amazing. She had so much control over how she was portraying that character. Basically, every scene was driven by her performance. In a certain way that made my job much easier.

In essence though, a film actor only needs to hit the perfect performance once, and then we can make it work. It’s about finding those very best moments. And I find we editors do that from the gut, you need a certain sensitivity for that. And that starts the very first moment you go watch the footage. You need to record your initial, honest response to a performance.

HULLFISH: Does your feeling or sense of a performance change when you are watching a single scene compared to when you are watching the overall arc of a character throughout the whole film?

HULLFISH: Does your feeling or sense of a performance change when you are watching a single scene compared to when you are watching the overall arc of a character throughout the whole film?

TER BURG: Not so much in this film but on some other films, definitely. You can find that you need a character to be less strong in order to favor another character’s arc. That sometimes requires you to go back into the footage and start ‘hunting’ with a new strategy.

HULLFISH: I understand that. When you watch the work of others, typically your peers and other professionals what are you looking for that tells you that that scene or film was edited well?

TER BURG: It’s a bit abstract, but for me it’s the sense that whoever’s telling you the story has control. Sometimes you’ll watch a scene and you will feel the scene is merely a registration of something that’s happening. But I love it when you feel that every single beat in the scene is under control. Of course you cannot fully rationalize that. And it can be hard to tell if it’s the editor or the director or the actors that are in control. But when I’m doing a workshop with students, with footage I know well, you can quickly tell if there is an intention behind the way a scene has been put together. Without that, a scene won’t work to the best of its ability.

HULLFISH: Do you have any editing heroes or are there specific editors that you point out to them that are excellent?

TER BURG: Oh, there are many. Like everyone else, I love Thelma Schoonmaker and everything she’s done with Martin Scorsese. It’s always amazing. It’s always special. It’s always fresh. And you get an absolute sense of control. I really love the work of William Goldenberg, there’s an innate sensitivity to what he does, that I really respond to. I admire Joe Walker, whom you interviewed for Art Of The Cut as well. He’s done so much amazing stuff and there is a musicality to it, as well as plain ballsiness.

TER BURG: Oh, there are many. Like everyone else, I love Thelma Schoonmaker and everything she’s done with Martin Scorsese. It’s always amazing. It’s always special. It’s always fresh. And you get an absolute sense of control. I really love the work of William Goldenberg, there’s an innate sensitivity to what he does, that I really respond to. I admire Joe Walker, whom you interviewed for Art Of The Cut as well. He’s done so much amazing stuff and there is a musicality to it, as well as plain ballsiness.

HULLFISH: Sitting on a single wide shot for 90 seconds was ballsy.

TER BURG: Or 17 minutes even. Of course that’s the director as well. But I highly respect him and his work. I’d also like to name Juliette Welfling, Jacques Audiard’s go-to editor, and she also did ‘Diving bell and the butterfly‘. She and Jacques can build these long immersive sequences, that build tension in a very musical way.

HULLFISH: Can you describe the schedule for this project? When did you start principal photography? When did shooting end? When did you bring in the director or other various people? And when did you go to DI?

TER BURG: They started principal photography in January and I was finishing another movie at the time (Alex van Warmerdam’s “SCHNEIDER VS. BAX”), but I did start watching dailies as soon as they came in. I had quite a busy two years, doing three films back to back, working on one film, turning that over to sound, start working on a second film, go back to the mix for the first one, etc. By the end of April I had done my editor’s cut and Paul came in and we worked until the end of July or so. We had already starting working on VFX and music of course, and then sound editorial started. ADR and color grading were done in Paris in September when I was working on my third project, “BRIMSTONE,” and then I joined him and the wonderful sound team in Paris in October for the final mix. Paul went back to the States, but I think he went back to Paris in January 2016 to do some final tweaks on the titles.

TER BURG: They started principal photography in January and I was finishing another movie at the time (Alex van Warmerdam’s “SCHNEIDER VS. BAX”), but I did start watching dailies as soon as they came in. I had quite a busy two years, doing three films back to back, working on one film, turning that over to sound, start working on a second film, go back to the mix for the first one, etc. By the end of April I had done my editor’s cut and Paul came in and we worked until the end of July or so. We had already starting working on VFX and music of course, and then sound editorial started. ADR and color grading were done in Paris in September when I was working on my third project, “BRIMSTONE,” and then I joined him and the wonderful sound team in Paris in October for the final mix. Paul went back to the States, but I think he went back to Paris in January 2016 to do some final tweaks on the titles.

HULLFISH: Tell me a little bit about the reception at Cannes. You just got back from there as we are recording this interview.

TER BURG: That was amazing. I had been to Cannes once before, with Van Warmerdam’s “BORGMAN”, which was the first Dutch film in 38 years to be selected for the main competition, and that was a huge thing. We were all very excited that “ELLE” was selected for Cannes but I am actually still on a bit of a high from how well the film was received there. To be honest, I had expected the response to the film would have been more divided. I figured it would be a film you’d either love or hate. “ELLE” is not an easy subject and it is a bit of an atypical film, with odd characters behaving strangely. And then when I flew into Cannes on the day of the premiere, the first press screening had just finished when I was driving into town, and the first enthusiastic reactions started to come in via text messages and social media. We then had a lunch with the entire team, and more and more raving reviews came in, from Le Monde to The Guardian and Hollywood Reporter and Variety. And that night we had our premiere at the Palais, this huge 2200-seat venue. The audience responded extremely well, you could just feel them being sucked into the story and its characters, so that was a terrific experience and it ended up being a long night with lots of champagne.

HULLFISH: (laughs) Congratulations on all the success of the “Elle” and “Brimstone.”

HULLFISH: (laughs) Congratulations on all the success of the “Elle” and “Brimstone.”

TER BURG: Thank you very much. Sony Classics picked “Elle” up for the US. I think it will open there in November. And also in the UK some time in the fall.

HULLFISH: Three final questions for you. What makes editing difficult or can you remember the last really difficult scene you had to cut and what made it difficult?

TER BURG: I would argue that every movie opening and every movie ending is challenging. There maybe one or two movies in your life with an easy opening or easy ending and for all the rest, you just keep working on those. In the case of “ELLE,” it was not so much the ending but it was the opening. It’s basically four shots or so and I think we have tried every possible way we could put them together. We tried a version with hardly any cuts, a version where we played it much longer. The opening scene sets the tone for everything that follows. So every small decision, like holding this shot there a second longer, or not even use it at all, will influence everything after that in the movie.

On other movies, it has been because the openings of films are often too introductory, with too much exposé, and you try to find a balance between keeping things going and giving the audience enough information to hook take in that will matter later on in the story.

And then there are scenes in every movie that somehow seem to require most of your energy and sensitivity, and even if you’re done cutting them, you will get to the mix and even then that scene will take more time and work. In “ELLE,” the 12 minute dinner scene was the one that we kept coming back to. It was never a bad scene but there were many options there, and we felt we needed to control that in a way that you could get through it and be absorbed in it and it would have significance, and it would be funny enough, and awkward enough in the right moments. That was just something that we just kept on tweaking. And I’m very happy we did, I think it’s quite a strong sequence in the very core of the film. I sometimes find myself stuck in a scene and I don’t know how to get out of it or how to fix it. And 9 times out 10 it will be because I’m not telling it simply enough or clearly enough. So I will quite often literally say to myself, out loud: ‘No, nope. Simpler. Make it simple. Make it work.’ I’ve told that to my students as well. If you try ‘sell’ 12 things at once, you’re usually not going to sell anything at all. If you try to sell one thing then the next then the next, and you do so with a certain amount of clarity and precision, it often works way better.

And then there are scenes in every movie that somehow seem to require most of your energy and sensitivity, and even if you’re done cutting them, you will get to the mix and even then that scene will take more time and work. In “ELLE,” the 12 minute dinner scene was the one that we kept coming back to. It was never a bad scene but there were many options there, and we felt we needed to control that in a way that you could get through it and be absorbed in it and it would have significance, and it would be funny enough, and awkward enough in the right moments. That was just something that we just kept on tweaking. And I’m very happy we did, I think it’s quite a strong sequence in the very core of the film. I sometimes find myself stuck in a scene and I don’t know how to get out of it or how to fix it. And 9 times out 10 it will be because I’m not telling it simply enough or clearly enough. So I will quite often literally say to myself, out loud: ‘No, nope. Simpler. Make it simple. Make it work.’ I’ve told that to my students as well. If you try ‘sell’ 12 things at once, you’re usually not going to sell anything at all. If you try to sell one thing then the next then the next, and you do so with a certain amount of clarity and precision, it often works way better.

Then again, that sounds really easy, but of course it’s about finding the right simplicity of it. You can be simple and not effective and that doesn’t help. You have to be simple and effective. I’m not trying to underplay what that is. But for me, thinking about it this way often helps.

HULLFISH: The simplest solution is to sit on the wide shot, but that doesn’t make it effective.

TER BURG: Right, well that’s the thing, or maybe it is effective. But it hardly ever is.

HULLFISH: I love the idea you spoke about when you judge the work of others is that displaying a sense of control over the material shows skill and the idea of how important the opening scenes are, the beginning of the film is really interesting. Two more questions before I let you go. You and I are both Avid guys and have known each other for a long time, what do you like and hate about Avid? Why do you use it? You could be editing on Premiere if you wanted to.

HULLFISH: I love the idea you spoke about when you judge the work of others is that displaying a sense of control over the material shows skill and the idea of how important the opening scenes are, the beginning of the film is really interesting. Two more questions before I let you go. You and I are both Avid guys and have known each other for a long time, what do you like and hate about Avid? Why do you use it? You could be editing on Premiere if you wanted to.

TER BURG: Yeah, I’m not against it. I just don’t have experience with it. There is something about the way you structure projects in Avid and the way you can control your footage that I really like. I must say that my first encounter with an NLE, when I was still in film school, was with a Lightworks system. I preferred that interface to Avid’s. But the main thing about Avid Media Composer is that, however clumsy some of the workflow may be, it will work. Especially on films with tight schedules (like nearly all of them these days). I’ve just finished a film called “BRIMSTONE,” starring Guy Pearce and Dakota Fanning. That film had a schedule that required us to start working on music and ADR in an early stage when we were still quite far from a locked picture cut. We knew we were going to be cutting all the way up until we were in final mix. So we needed a lot of flexibility going back and forth between sound editorial and picture editorial, and sending AAF’s to sound editorial is simple and robust. I’ve seen many projects using other software where these turnovers to sound were a nightmare.

That said, I don’t think any of these tools are perfect. Pro Tools is great for a lot of things and horrible in many, many other ways, and I don’t think that the collaboration between Media Composer and Pro Tools is anywhere near perfect. But at least, I will know that if I send something to someone today, they will be able to open that and work on it today. And that’s just something that other solutions haven’t proven to do for me.

HULLFISH: Do you have specific things that you really feel, some editing wisdom that you have or what are some of things you tried to impart to your assistant editors or your students?

TER BURG: In my workshops I try to make them aware of what they do by analyzing their work. A lot of what we do is instinctive, but when you’re trying to determine why something is working or not, you sometimes need to rationalize it. That doesn’t always work but sometimes when you’re stuck, you need to say to yourself, ‘So I am starting with this shot and it tells me this then I cut to that shot. Why do I cut to that shot? What does it mean that I showed the audience that shot? Why do I go there and not some other route?’ It’s not a thought process that you can maintain when you’re editing cause you would go insane, but if somehow you are stuck or you don’t know what you’ve done is right, that makes a lot of sense. Rationalizing it: thinking ‘Why is it structured in this way? Why did I do this? What does this mean?’”

HULLFISH: Great talking to you, my friend!

TER BURG: My pleasure, Steve! You know I’m a fan of your Art of the Cut series, I feel honored to now be part of it.

To read more interviews check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now