ART OF THE CUT talks to Philip Harrison about the distinctive cutting approach of the binge-worthy TV series Mr. Robot. Harrison’s work on the series was nominated for an ACE EDDIE for Best Edited One Hour Series (Commercial) for his episode,“eps2.4m4ster-s1ave.aes.”

HULLFISH: Your previous editing gigs were quite different from Mr. Robot.

HARRISON: Previous to Mr. Robot, I had been working on Glee which is obviously a much different show in terms of its content and style. Ryan Murphy, who produced that show, was going for a bright, fun, immediate feel so the cutting is briskly paced with important dialogue always on camera, moment to moment the viewer should always know where they are in the story. For musical sequences, the rhythm of the music guided the cutting pattern and I was always on the lookout for interesting camera movement that sold the emotion of a particular song. When I started working on Mr. Robot, I had to let go of that sort of rhythm and shift over to the Mr. Robot rhythms. That was actually a big leap for me initially- to let things pause and let shots play- take in what the characters might be thinking. It was a question of trusting the story. I’m always concerned that the audience is understanding and I’m always worried if they’re ahead of the story or behind the story. Editing Mr. Robot, these concerns were tricky to judge because the storylines play out over a long amount of time and it isn’t always clear what the character motivations are. The creator, Sam Esmail, wanted that ambiguity. It’s inherent to the show – our lead character, Elliot, isn’t always forthcoming and honest with the audience or himself. Anyway, It always takes extra passes of your cut to feel like you’ve really gotten the right rhythm and the right story and character beats. And that the subtext of the story is going to hold the viewer.

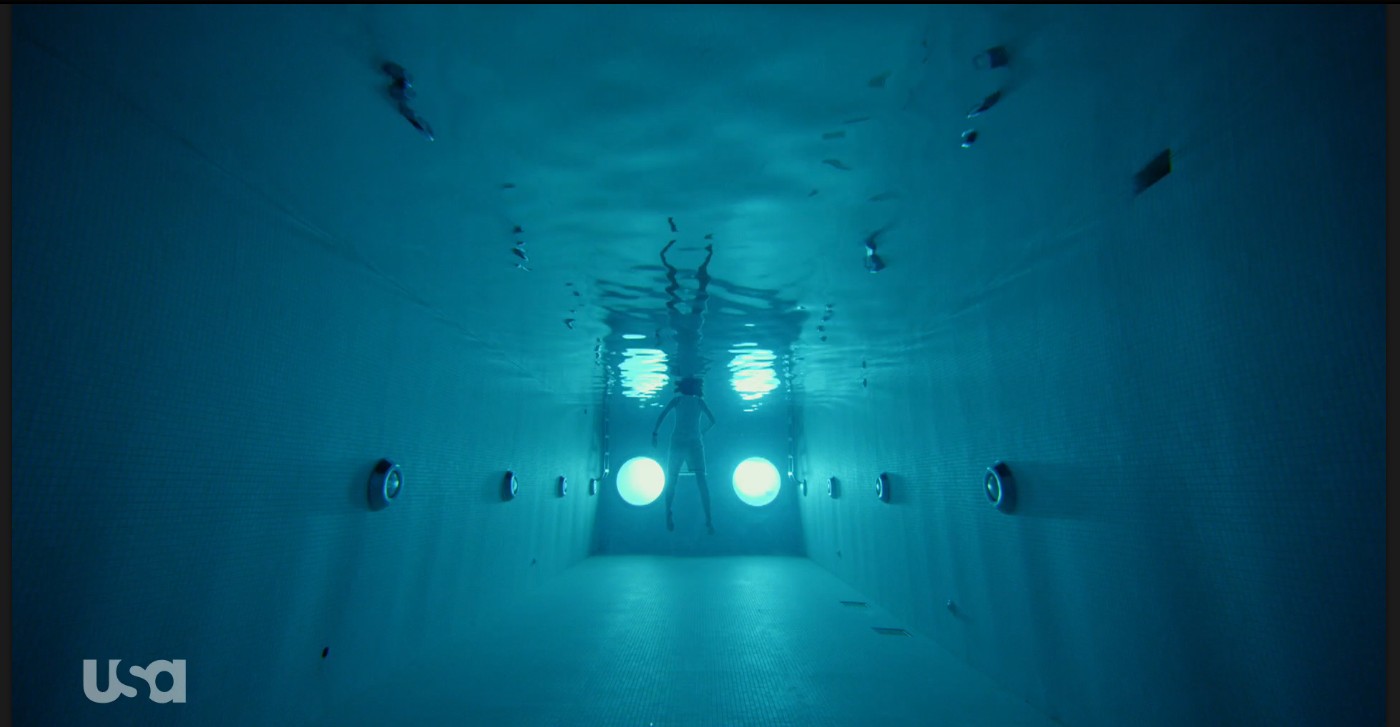

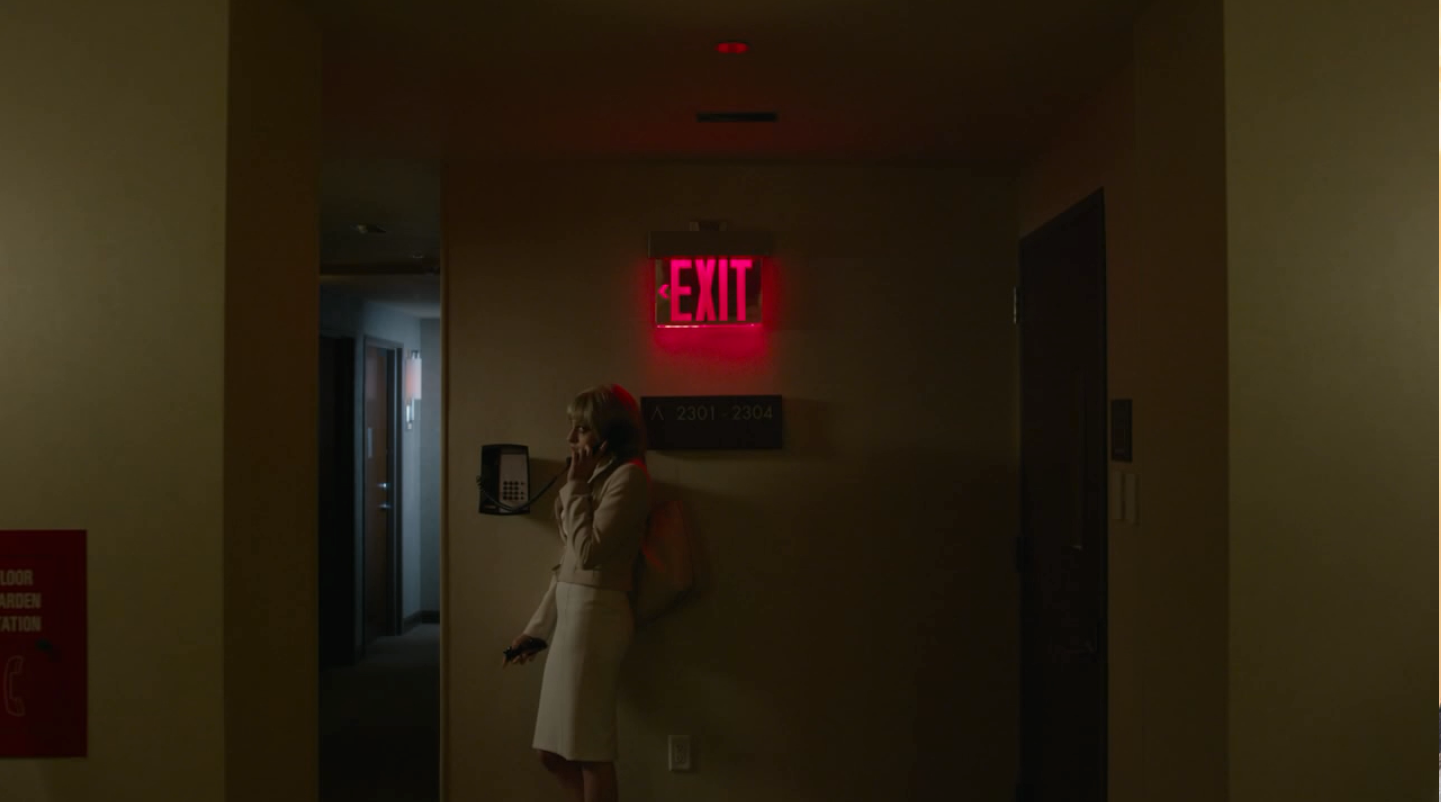

HULLFISH: You were nominated for an ACE EDDIE for an episode that had a really interesting series of jumpcuts in a hotel break-in. (Season 2, Episode 6, “eps2.4 m4ster-s1ave.aes”)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rrVBGf-u-0A

HARRISON: That scene was a little unusual for Mr. Robot. As opposed to the usual dark moodiness, it had a sort of classic “heist” scene feel, like something you’d see in Ocean’s 11; The character is using her charisma and hacking skills to break into a hotel room. We wanted to be able to accelerate the energy of it all – really manipulate the audience where we could ramp up the energy and then slow it down and then ramp it up again and the jump cuts were a logical extension of that. It was really fun: for my first cut I just built the sequence “as is.”, without jump cuts. Then I just played with the energy and tried to figure out how much information we actually needed and how little we could get away with telling. The nervous energy created by the jump cuts in rhythm with the song propelled the scene. A little later in the sequence, we go in the opposite direction with a 3-4 minute take with no cuts that has a different way of creating tension.

HULLFISH: Well it’s interesting that you keep mentioning energy because I was just talking to Joi McMillon who edited Moonlight and there’s a bunch of jump cuts in that piece and they’re all done for energy and to get into a character’s head. Thelma Schoonmaker says the same thing about a lot of the jump cuts she does, it is definitely a way to infuse some energy into a sequence, I’m trying to figure out what the psychology of that is.

HULLFISH: Well it’s interesting that you keep mentioning energy because I was just talking to Joi McMillon who edited Moonlight and there’s a bunch of jump cuts in that piece and they’re all done for energy and to get into a character’s head. Thelma Schoonmaker says the same thing about a lot of the jump cuts she does, it is definitely a way to infuse some energy into a sequence, I’m trying to figure out what the psychology of that is.

HARRISON: It feels very physiological as well. There’s something about a jump cut – it’s a break in our perceptual reality of what’s going on in front of us. It can feel like if you bump your head you feel a little jump, you know? You’re also compressing time- anytime you compress time in a cut you feel a surge of energy leaping forward. And if you have a series of jump cuts, it’s a rhythm, you feel it musically, like a drumbeat.

There’s also a more thematic intention with some of the jump cuts in Mr. Robot. My first episode in season 1, “eps1.3_da3m0ns.mp4”, had a series of scenes where Elliot is going through morphine withdrawal. He’s really in a bad place, sweating, starting to hallucinate. We wanted to come up with a way to really accentuate that feeling and place the viewer in that experience. I experimented with step printing the image which gave it a very visceral kind of feeling, but then I also added jump cuts and duplicated frames to give it a sort of a stutter feeling; almost like a tremor. It gave us this feeling of getting into Elliot’s mind a little bit, that this was a fractured experience for him. In the season 1 finale, there’s a moment where Elliot is on the subway, he’s in crisis mentally and completely locked inside himself. Rami Malek’s performance in the dailies went through a range of emotions: happiness, crying, despair, blank. That was an opportunity to jump cut the footage so that you felt Elliot’s splintered personality – that his brain was quickly shuffling through these different emotions almost like a hard drive. The jump cut has definitely become a part of the Mr. Robot language.

There’s also a more thematic intention with some of the jump cuts in Mr. Robot. My first episode in season 1, “eps1.3_da3m0ns.mp4”, had a series of scenes where Elliot is going through morphine withdrawal. He’s really in a bad place, sweating, starting to hallucinate. We wanted to come up with a way to really accentuate that feeling and place the viewer in that experience. I experimented with step printing the image which gave it a very visceral kind of feeling, but then I also added jump cuts and duplicated frames to give it a sort of a stutter feeling; almost like a tremor. It gave us this feeling of getting into Elliot’s mind a little bit, that this was a fractured experience for him. In the season 1 finale, there’s a moment where Elliot is on the subway, he’s in crisis mentally and completely locked inside himself. Rami Malek’s performance in the dailies went through a range of emotions: happiness, crying, despair, blank. That was an opportunity to jump cut the footage so that you felt Elliot’s splintered personality – that his brain was quickly shuffling through these different emotions almost like a hard drive. The jump cut has definitely become a part of the Mr. Robot language.

HULLFISH: The use of music to me is really interesting in this series. One of the hardest things with music is determining when exactly to start it and stop it and there are some really cool examples in that FBI headquarters in your nominated episode.

HULLFISH: The use of music to me is really interesting in this series. One of the hardest things with music is determining when exactly to start it and stop it and there are some really cool examples in that FBI headquarters in your nominated episode.

HARRISON: That is a very playful stylized sequence. The song, “Gwan” by The Suffers is a very uptempo soul track with a big, brassy, female vocal. It helps justify these really broad shifts in energy. There are moments in the action where the hacking scheme feels like it might be derailed and the sudden cuts to silence help amp up the suspense. This is the oner scene I was talking about so the music also helps support that long take – gives it a pulse.

HULLFISH: Another scene I wanted to talk about was the scene with the car ride at the end of the episode with a young actor playing Mr. Robot as a child. You were able to get some great performances out of the kid. Can you talk to me a little bit about the little plays of subtle emotion across his face and trying to screen dailies and gather that stuff?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bnKf0Ei014c

HARRISON: That scene is one of my favorites. At the end of the day, underneath the paranoia and cynicism, the show has a really big heart and to have a scene that’s about the relationship between a father and his son – to have it played out in such a sweet, sensitive way was really gratifying for me. They shot it with a process car, 2 cameras for every setup; I probably had 8 hours of footage for a 4-minute scene. I went through and broke down the footage into the tiniest portions possible for every line of dialogue and every beat where I thought there was subtext that required an emotional reaction. Doing that lets me get really familiar with the footage. Some of the reactions and some of the lines of dialogue we had at least 10 different possibilities for young Elliot and for his father. I kind of knew from the beginning that the boy’s face was going to be the most important part, so a lot of the dialogue plays just over his face and you just read so much into him. It was interesting to experiment with the dialogue against the boy’s reactions – the father talking to him about being fired and that he has cancer – and just trying different pieces of the boy and seeing what feels real and what gives you that little emotional sort of jigger in your stomach.

HULLFISH: You said that you broke the dailies down into granular segments. How are you doing that? With selects reels or sub clips or what are you doing?

HULLFISH: You said that you broke the dailies down into granular segments. How are you doing that? With selects reels or sub clips or what are you doing?

HARRISON: I like to use Avid ScriptSync when I’m working with a director because it’s really fast for showing options. But when I’m cutting on my own I don’t use ScriptSync at all because I need to just go through the footage to understand what I have and kind of internalize it all. I’ll watch the dailies and then I will create what I call “breakdown” sequences for each scene. In the breakdown sequences, I will line up smaller sections of all the takes from each camera position. So, One sequence of all of Elliot’s dialogue, one for Mr. Robot’s, and one for the wide shots, etc. The breakdown is the individual lines of dialogue or reactions all lined up together but it can also be longer hunks of the scene according to what seems the most helpful. I find I need to compare performances directly against each other to make a choice. By putting lines of dialogue, reactions or moments of action together, side by side, the right take seems to pop out. I compare it to photographers when they look at photos on a contact sheet and they have their loupe and they go from photo to photo and by just popping from one to the next to the next you can suddenly see: “Oh that’s the one I want to use.” That’s kind of my process. Things get vague for me if I don’t break down into fairly small pieces. But it’s also just a way to make sure that I have seen everything and that I really have internalized the material.

HULLFISH: A lot of people use KEM rolls or selects rolls where you just kind of run all the dailies from action to cut one after another, but that can, for a decent size scene, that can be 45 minutes, 25 minutes, and you can’t keep 45 minutes of performances in your brain, but if you break that 45 minutes down into 5 minutes sections and go “Okay, this is 5 minutes of the first 15 seconds or 10 seconds of the scene.” Then all of a sudden you’re like “5 minutes. I can figure out 5 minutes worth of performances.”

HULLFISH: A lot of people use KEM rolls or selects rolls where you just kind of run all the dailies from action to cut one after another, but that can, for a decent size scene, that can be 45 minutes, 25 minutes, and you can’t keep 45 minutes of performances in your brain, but if you break that 45 minutes down into 5 minutes sections and go “Okay, this is 5 minutes of the first 15 seconds or 10 seconds of the scene.” Then all of a sudden you’re like “5 minutes. I can figure out 5 minutes worth of performances.”

HARRISON: Yea, I’ve tried those KEM rolls but sort of get lost in that method. By breaking it down into smaller pieces, I’m better able to manage things.

HULLFISH: So basically what you’re doing is selects reels broken down to lines.

HARRISON: I’ve edited documentaries with a huge amount of archival material. In that situation, if you try to cut something without getting your ducks in a row and breaking it down into pieces, you can just forget it. You won’t be able to cut a documentary. I come from that mindset. I like to get everything in order, get all the pieces in my brain, but then get them easily available and then I’m ready to do it. I know I’ve got everything within arms-length.

HARRISON: I’ve edited documentaries with a huge amount of archival material. In that situation, if you try to cut something without getting your ducks in a row and breaking it down into pieces, you can just forget it. You won’t be able to cut a documentary. I come from that mindset. I like to get everything in order, get all the pieces in my brain, but then get them easily available and then I’m ready to do it. I know I’ve got everything within arms-length.

HULLFISH: There’s a shocking edit at the end of this episode. Tell me about that. It’s a decision of finding the perfect moment, right, to make that cut?

HARRISON: I’d love to be able to take a huge amount of credit for that but that was Sam Esmail’s plan. At the end of this dramatic scene, 13-year-old Elliot’s father (Christian Slater) gives him the chance to name his new computer business. Elliot closes his eyes to think through what it could be called and just as he opens his eyes…we cut to black before he can say, “Mr. Robot”. Actually, in my first cut, I had him saying the line even though I knew we would want to cut that off. But they shot it with the dialogue and I wanted Sam Esmail to have a chance to see it that way. By cutting off the line, you give the audience the chance to make the connection. Anyone who’s been watching the series will make that leap. You also put the focus on what’s going on with Elliot. He’s not just naming this computer business, he’s starting to build the whole idea of his alter ego, Mr. Robot.

HARRISON: I’d love to be able to take a huge amount of credit for that but that was Sam Esmail’s plan. At the end of this dramatic scene, 13-year-old Elliot’s father (Christian Slater) gives him the chance to name his new computer business. Elliot closes his eyes to think through what it could be called and just as he opens his eyes…we cut to black before he can say, “Mr. Robot”. Actually, in my first cut, I had him saying the line even though I knew we would want to cut that off. But they shot it with the dialogue and I wanted Sam Esmail to have a chance to see it that way. By cutting off the line, you give the audience the chance to make the connection. Anyone who’s been watching the series will make that leap. You also put the focus on what’s going on with Elliot. He’s not just naming this computer business, he’s starting to build the whole idea of his alter ego, Mr. Robot.

HULLFISH: Tell me a little bit about the beginning of that episode – it’s a spoof on an 80s sitcom. Did you watch any 80s sitcoms to prepare?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ow_CcZ2dWWw

HARRISON: When I was working on Glee, I cut a sitcom spoof sequence where a character gets bumped on the head and all of a sudden you’re in a Friends episode including a replica of a Friends title sequence and all of our Glee characters have taken the place of Friends characters. For that, I looked at Friends episodes and matched the style. It had the laugh track, music hooks, and the 3 camera cutting pattern. So I had some familiarity with the style. Flash forward to Mr. Robot: Every season Sam likes to do something that’s going to totally throw the train off the rails and just really sort of screw with the audience’s expectations. Last year I got to cut the episode where Elliot is shot in a drug den and the audience is thrown into a 10-15 minutes dream sequence.

This season we opened the episode, “eps2.4_m4ster-s1ave.aes”, with Elliot lost in a 20 minute 90s sitcom episode where he’s with his family on a road trip. Since I already had some familiarity with the sitcom style I did a limited amount of research. Instead, my focus was on amplifying the contrast between the upbeat style of the sitcom with the dark undertone of our Mr. Robot story- The main solution was to play it straight on both fronts. For the title sequence, Sam had me match the Full House title sequence exactly. But instead of the family house in the Full House sequence, we have a wide shot of the town with a nuclear power plant! Then Sam connected with the original composers of the Full House music to write a whole new song called “A World Gone Insane”! They also did all the musical bumpers in this self-contained “sitcom”. I temped my cut with a laugh track, but in the sound process they brought in the actual people who do laugh tracks for all of the sitcoms today and they made a track that is authentic to these shows.

The next things were to get the tone of the performances right- Sam shot a range from all the actors. Some were slightly more in the “winking” direction but we chose performances that were as straight as possible. That has its exceptions but we definitely leaned more towards the straight performances. We didn’t want it to be a wink, we wanted it to play as this contrast of the sitcom style with the dark, real undertone. For instance, in the opening sequence, we have the shot introducing Elliot as he reacts to falling through a glass window. We had a sort of “Gee Wiz!” take but we went with the take where Elliot seems confused and upset, consistent with the character. The larger effect comes from the contrast of this reaction with the upbeat theme music. It’s more of a warped upsetting feeling – a joke you don’t really want to be in on.

The next things were to get the tone of the performances right- Sam shot a range from all the actors. Some were slightly more in the “winking” direction but we chose performances that were as straight as possible. That has its exceptions but we definitely leaned more towards the straight performances. We didn’t want it to be a wink, we wanted it to play as this contrast of the sitcom style with the dark, real undertone. For instance, in the opening sequence, we have the shot introducing Elliot as he reacts to falling through a glass window. We had a sort of “Gee Wiz!” take but we went with the take where Elliot seems confused and upset, consistent with the character. The larger effect comes from the contrast of this reaction with the upbeat theme music. It’s more of a warped upsetting feeling – a joke you don’t really want to be in on.

HULLFISH: You mentioned a couple of other episodes or at least one other episode that you wanted me to take a look at. What specifically was in that that you were proud of or that you feel is interesting to talk about?

HARRISON: My first episode of season 2,” eps2.1_k3rnel-pan1c.ksd”, was massive. My first cut was an hour and a half long and I think eventually it came down to about an hour and four minutes which is long for television. It had a lot of characters and storylines. There were some pretty hefty montages. There were flashback scenes that only tangentially related to the rest of the show. We also had scenes that shifted quickly between “reality” and “fantasy” where we were manipulating the audience’s perceptions.

HARRISON: My first episode of season 2,” eps2.1_k3rnel-pan1c.ksd”, was massive. My first cut was an hour and a half long and I think eventually it came down to about an hour and four minutes which is long for television. It had a lot of characters and storylines. There were some pretty hefty montages. There were flashback scenes that only tangentially related to the rest of the show. We also had scenes that shifted quickly between “reality” and “fantasy” where we were manipulating the audience’s perceptions.

Originally, the script indicated a sort of checker-boarded pattern of the different characters arcs that would work in a very straightforward manner; dispense a little information, move on to the next character, a little more information, shift to the next character, etc. But when we got into the process of editing, it felt too arbitrary. We realized that we needed to restructure so the viewer felt like they were in the moment – We wanted to create the feeling that we were moving to the next piece of story because the story required it and that the next scene we went to was the only logical scene that we could go to next. It took quite a bit of trial and error to get the cut to feel well balanced.

HULLFISH: What did it end up being that delivered that sense that – instead of being arbitrary – that it was necessary to go to the next part of the story? Was it a sense of answering a question, like almost like one scene, would pose a question the next scene would answer?

HULLFISH: What did it end up being that delivered that sense that – instead of being arbitrary – that it was necessary to go to the next part of the story? Was it a sense of answering a question, like almost like one scene, would pose a question the next scene would answer?

HARRISON: First we simplified the story arcs. Instead of Intercutting Elliot’s story with Dom and Angela’s in act 1-3, we condensed his storyline into acts 1 and 2 and held off introducing the Dom and Angela arcs until act 3 or act 4, By playing out Elliot’s story longer, we found that you were able to track it better. And it felt like there was a more satisfactory ending with his storyline before you moved on to the new character. You were ready to move on to the other characters. So, there was a lot of that type of work.

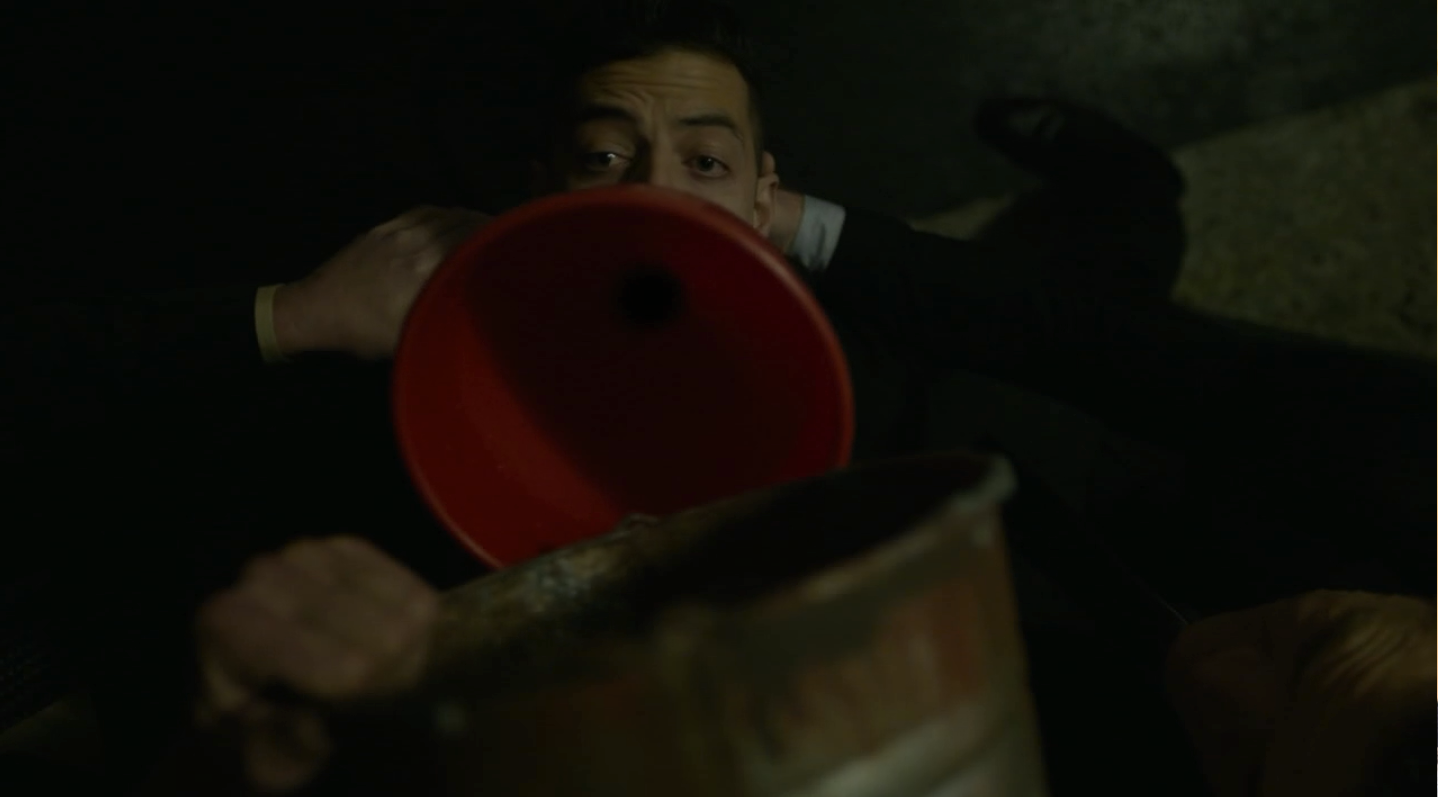

In respect to the reality/fantasy issue, we needed to make some alterations to accentuate the audience manipulation we were going for; In one sequence, Elliot is being confronted by his alter ego, Mr. Robot, and he takes a fist full of Adderall as a way to disconnect. This propels Elliot into a fantasy sequence where “men in black” apprehend him and force cement down his throat before a smash cut takes us back to reality. Originally we had that section as just one long sequence but it played much too long and it felt like the audience would be ahead of things. You could tell that it was “Oh it must be in Elliot’s head. This has to be a fantasy”. One thing we did was add some ADR when the “men in black” do appear that misleads the audience to think “Oh maybe this is the FBI, so maybe this is real.” Then we split the sequence up with another unrelated scene with other characters. Putting that interruption scene in there broke it up like a sort of cliffhanger- it put the audience back behind the story, not sure if the events are real or not, instead of in front of it. Finally, we whittled down this section to the barest essential elements. When you have fantasy elements, a little goes a long way. Too much and the audience feels the fantasy. Keeping it minimal kept the viewer in the moment until we were ready to reveal the truth. We felt the audience would be behind the story at that reveal.

In respect to the reality/fantasy issue, we needed to make some alterations to accentuate the audience manipulation we were going for; In one sequence, Elliot is being confronted by his alter ego, Mr. Robot, and he takes a fist full of Adderall as a way to disconnect. This propels Elliot into a fantasy sequence where “men in black” apprehend him and force cement down his throat before a smash cut takes us back to reality. Originally we had that section as just one long sequence but it played much too long and it felt like the audience would be ahead of things. You could tell that it was “Oh it must be in Elliot’s head. This has to be a fantasy”. One thing we did was add some ADR when the “men in black” do appear that misleads the audience to think “Oh maybe this is the FBI, so maybe this is real.” Then we split the sequence up with another unrelated scene with other characters. Putting that interruption scene in there broke it up like a sort of cliffhanger- it put the audience back behind the story, not sure if the events are real or not, instead of in front of it. Finally, we whittled down this section to the barest essential elements. When you have fantasy elements, a little goes a long way. Too much and the audience feels the fantasy. Keeping it minimal kept the viewer in the moment until we were ready to reveal the truth. We felt the audience would be behind the story at that reveal.

HULLFISH: And that’s a critical place for the audience to be, right?

HULLFISH: And that’s a critical place for the audience to be, right?

HARRISON: Absolutely critical for that sequence. Overall, this was a process that the entire episode had to go through. It was in the subtleties of restructuring and manipulating everything so that you felt the threads were being told in the right order. So that was the most interesting problem-solving episode of the season.

HULLFISH: You were talking about all this restructuring of this episode and it makes me think: as an editor you’re a technician that knows how to run the equipment, you’re a visualist that knows how to find the most compelling visual imagery and cut it in the most interesting way, you’ve got a musician’s sense of pacing and rhythm, but you also have to have real storytelling chops to be able to be part of a room that is restructuring a story radically. Talk to me about being a story teller.

HARRISON: I’m very much a process-oriented editor. In my first passes, I’m most focused on trying to make sense of the storylines, not worrying about the bells and whistles. Looking for the character motivations and really cutting everything based on that. Then on repeated passes … this stuff it doesn’t all happen at once- I remember when I was a younger editor I thought I had to know how everything was going to go together and what I found is you don’t. You just need to make logical sense one cut at a time and the totality is revealed to you… I like those first passes to really get things laid out, screen direction, most important thing is character, where are the characters at emotionally. Subtext, Who’s the actor? Who’s the acted upon? What are their reactions to these things? Keep it simple, and then you go to the beginning again and watch things narratively and see how those threads are feeling across the entire episode. I never dip into a scene randomly. I always like to go from the very beginning because that informs, for me, the narrative sense and I feel like I’m on firm footing. So I continue to make passes of the material and as things continue to fall into place then my attention can turn more towards the specifics. I start adding sound effects. BTW, after my first scene passes, I handed them off to the assistant editor, Gordon Holmes, to lay in background, sound effects all the stuff that makes it feel physically, viscerally real. Then I can start really getting in there and playing with the scenes in the musical sense that you’re talking about. I’ll see things that I didn’t see previously. More and more you’re going in and doing the detail work that really starts bringing it to life. Then the director comes in and it becomes a collaborative process. On Mr. Robot we make many passes before we get to the final version because it has so many layers.

HARRISON: I’m very much a process-oriented editor. In my first passes, I’m most focused on trying to make sense of the storylines, not worrying about the bells and whistles. Looking for the character motivations and really cutting everything based on that. Then on repeated passes … this stuff it doesn’t all happen at once- I remember when I was a younger editor I thought I had to know how everything was going to go together and what I found is you don’t. You just need to make logical sense one cut at a time and the totality is revealed to you… I like those first passes to really get things laid out, screen direction, most important thing is character, where are the characters at emotionally. Subtext, Who’s the actor? Who’s the acted upon? What are their reactions to these things? Keep it simple, and then you go to the beginning again and watch things narratively and see how those threads are feeling across the entire episode. I never dip into a scene randomly. I always like to go from the very beginning because that informs, for me, the narrative sense and I feel like I’m on firm footing. So I continue to make passes of the material and as things continue to fall into place then my attention can turn more towards the specifics. I start adding sound effects. BTW, after my first scene passes, I handed them off to the assistant editor, Gordon Holmes, to lay in background, sound effects all the stuff that makes it feel physically, viscerally real. Then I can start really getting in there and playing with the scenes in the musical sense that you’re talking about. I’ll see things that I didn’t see previously. More and more you’re going in and doing the detail work that really starts bringing it to life. Then the director comes in and it becomes a collaborative process. On Mr. Robot we make many passes before we get to the final version because it has so many layers.

One fun thing on Mr. Robot, coming from a documentary background, is the cinematic montages that are part of many of the episodes. It’s a thrill to take a bunch of different montage pieces and find the rhythm and find the flow and play things off of each other and invent moments. In a montage sequence where Elliot is flying high on Adderall, we had one moment where Sam had designed a wide profile shot on the side of the street with Elliot walking down the sidewalk. Sam wanted to literalize the idea of computer imagery in this moment, so he wanted to create a visual effect that blurred Elliot walking across frame – like a human screen saver image. As I worked with the footage, I noticed that Rami Malek had performed takes increasingly energetic. I got the idea that we could split screen together all of those different takes so you see this spectrum of Elliots. It was another way to show the splintered personality. It sort of started with Sam’s intent and evolved into another thing that related more to the character’s inner life. It’s one of the fun things of editing when you can come up with a way to cut something and suddenly it comes to life. And that sort of work comes in the later passes when you’ve removed some basic obstacles and you can just get in the groove and be inventive.

One fun thing on Mr. Robot, coming from a documentary background, is the cinematic montages that are part of many of the episodes. It’s a thrill to take a bunch of different montage pieces and find the rhythm and find the flow and play things off of each other and invent moments. In a montage sequence where Elliot is flying high on Adderall, we had one moment where Sam had designed a wide profile shot on the side of the street with Elliot walking down the sidewalk. Sam wanted to literalize the idea of computer imagery in this moment, so he wanted to create a visual effect that blurred Elliot walking across frame – like a human screen saver image. As I worked with the footage, I noticed that Rami Malek had performed takes increasingly energetic. I got the idea that we could split screen together all of those different takes so you see this spectrum of Elliots. It was another way to show the splintered personality. It sort of started with Sam’s intent and evolved into another thing that related more to the character’s inner life. It’s one of the fun things of editing when you can come up with a way to cut something and suddenly it comes to life. And that sort of work comes in the later passes when you’ve removed some basic obstacles and you can just get in the groove and be inventive.

HULLFISH: This new environment of TV with much more complicated and interesting plots and more cinematic style – the schedules are also radically different now. Tell me a little bit about the schedule. The kind of restructuring you are talking about can’t possibly happen in 4 days.

HULLFISH: This new environment of TV with much more complicated and interesting plots and more cinematic style – the schedules are also radically different now. Tell me a little bit about the schedule. The kind of restructuring you are talking about can’t possibly happen in 4 days.

HARRISON: No it doesn’t.

HULLFISH: I’m really interested in specifics.

HARRISON: Season one was a little more typical in that each episode was directed by a different director and they shot for eight days per episode. I probably had 3-4 days after that to pull my editor’s cut together and then we had four days with each individual director and then we would have however much time was needed in the producer’s cut with Sam Esmail. In season two things were very atypical in that we were block-shooting the episodes. We had three blocks. The first four episodes were shot in the first block. The second three episodes were shot in the second block, and then the final four episodes were shot in the final block. As it turned out my first episode bled into the second block of shooting and my second episode bled into the third block. So we had multiple episodes shooting over three or four months of time with airdates starting during production. On my first episode, I worked on the editor’s cut for a couple months because Sam was shooting and unavailable and I kept getting new scenes. But then I was starting to get dailies for my second episode and then all of a sudden Sam would have availability to start working on his version of the first episode. It took a lot of stamina to stay focused while jumping around between episodes like that. When I’m alone editing, I just get in a much more intuitive place. When you’re working with a director you have to do your best to keep that part alive while also using a good portion of your brain to communicate, to let the director know that you’re listening to them. I actually had a mirror set up, because we had a fairly small editing room, I had a mirror set up on my desk so that I could look in the mirror and see Sam when he was talking to me and to watch his reactions sometimes during screenings. We all thought it was a little funny and weird but it was the easiest way for me to be able to listen and really hear what he was saying without having to crane around all the time. I really needed to keep my hands on the keyboard the whole time if we were going to meet our deadlines. The other editors – Franklin Peterson and John Petaja – we would always look at each other’s work. The whole post department actually – Sam would have screenings of everybody’s cut and we would do a round table and talk through what the issues were and then go back into the rooms and work our way through those notes. We had a really smart crew so it was a really great way to hone each of the episodes!

HARRISON: Season one was a little more typical in that each episode was directed by a different director and they shot for eight days per episode. I probably had 3-4 days after that to pull my editor’s cut together and then we had four days with each individual director and then we would have however much time was needed in the producer’s cut with Sam Esmail. In season two things were very atypical in that we were block-shooting the episodes. We had three blocks. The first four episodes were shot in the first block. The second three episodes were shot in the second block, and then the final four episodes were shot in the final block. As it turned out my first episode bled into the second block of shooting and my second episode bled into the third block. So we had multiple episodes shooting over three or four months of time with airdates starting during production. On my first episode, I worked on the editor’s cut for a couple months because Sam was shooting and unavailable and I kept getting new scenes. But then I was starting to get dailies for my second episode and then all of a sudden Sam would have availability to start working on his version of the first episode. It took a lot of stamina to stay focused while jumping around between episodes like that. When I’m alone editing, I just get in a much more intuitive place. When you’re working with a director you have to do your best to keep that part alive while also using a good portion of your brain to communicate, to let the director know that you’re listening to them. I actually had a mirror set up, because we had a fairly small editing room, I had a mirror set up on my desk so that I could look in the mirror and see Sam when he was talking to me and to watch his reactions sometimes during screenings. We all thought it was a little funny and weird but it was the easiest way for me to be able to listen and really hear what he was saying without having to crane around all the time. I really needed to keep my hands on the keyboard the whole time if we were going to meet our deadlines. The other editors – Franklin Peterson and John Petaja – we would always look at each other’s work. The whole post department actually – Sam would have screenings of everybody’s cut and we would do a round table and talk through what the issues were and then go back into the rooms and work our way through those notes. We had a really smart crew so it was a really great way to hone each of the episodes!

HULLFISH: The mirror idea is very funny. That’s a great idea.

HULLFISH: The mirror idea is very funny. That’s a great idea.

HARRISON: As you know, a big part of the job is the diplomacy and communication skills that you can bring to working with the director even as you have to be looking at a screen and a keyboard. I think a big part of human communication is looking someone in the face so they actually see that you’re listening and so you can actually take in what they’re saying. There’s a feeling of trust that comes from that. So I generally try to set up my cutting room so that whoever I’m working with is not behind me because I find it difficult to crane around. I much prefer if they’re just to the side. And I try to engrain in assistants that work with me – it’s always more important for me, working with a director, for them to know that I’m listening to them and taking it in and really trying to support what they’re asking for. Even if I have ideas that I think might be helpful, often I will hold off on expressing those ideas. I know by being so centrally involved with the process, I’m automatically going to put my stamp on the project. I can always bring my ideas up at any time. It’s more important to let the director know that you’re there for them and you’re really taking in what they want.

HULLFISH: Yeah I was just talking to my assistant about this because I sent out an edit in a certain state and he was asking me about “well don’t you want to tell them this is wrong or this has got to be changed?” I said, “No.” He will see that he will have his own ideas of what has to be changed and what doesn’t have to be changed. Get your ego out of the way and let the director do their job. If some of the stuff gets missed by the director then I will bring it up, but I’m not going to bring it up right now.

HARRISON: Absolutely. I’ve definitely learned the hard way. If your director doesn’t think that you’re there for them it’s very difficult to get work done and to feel the collaboration happening. You really have to be available.

HULLFISH: Exactly.

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish

Special thanks to Noah Adams for his transcription of this interview.

The first 50 Art of the Cut interviews were curated into a book – broken down by topic. This book reads like a virtual roundtable discussion of editing and is a rare glimpse into the art of modern film and TV editing. Together these editors have won more than a dozen Oscars and have been nominated for more than three dozen more, not to mention numerous Emmys and Eddies. All told, the book contains advice gleaned from more than 1,000 years of editing experience.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now