Mick Audsley is the BAFTA-winning editor of such films as Dangerous Liaisons, 12 Monkeys, Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, Interview with the Vampire, and The Avengers. It’s a career as an editor that goes back to the mid 1970s, so a paragraph really doesn’t do it justice. Check out his imdb filmography here.

Also, check out Mick’s film networking and education project, SprocketRocket here: www.sprocketrocketsoho.com

In this wide-ranging interview, we focus on his collaboration with director/producer/star Kenneth Branagh on Murder on the Orient Express.

(This interview was transcribed with SpeedScriber. The entire interview was transcribed within 15 minutes of completing the Skype call. Thanks to Martin Baker at Digital Heaven)

HULLFISH: As we’re talking, Murder on the Orient Express is still being finalized.

AUDSLEY: Basically we just finished mixing, and the last VFX are coming in. We’ll be into delivery next week while I’m walking in the mountains and seaside of Crete! I’m looking forward to it.

HULLFISH: So you are taking a little break. It’s always a trick, right, when you’re between one movie and another, whether you’ve got to jump right to the next movie or whether you’ve got too much time in between?

AUDSLEY: Definitely, definitely. I’m really looking forward to a break. This has been a year for me, so it’s a long time.

HULLFISH: When was principal photography?

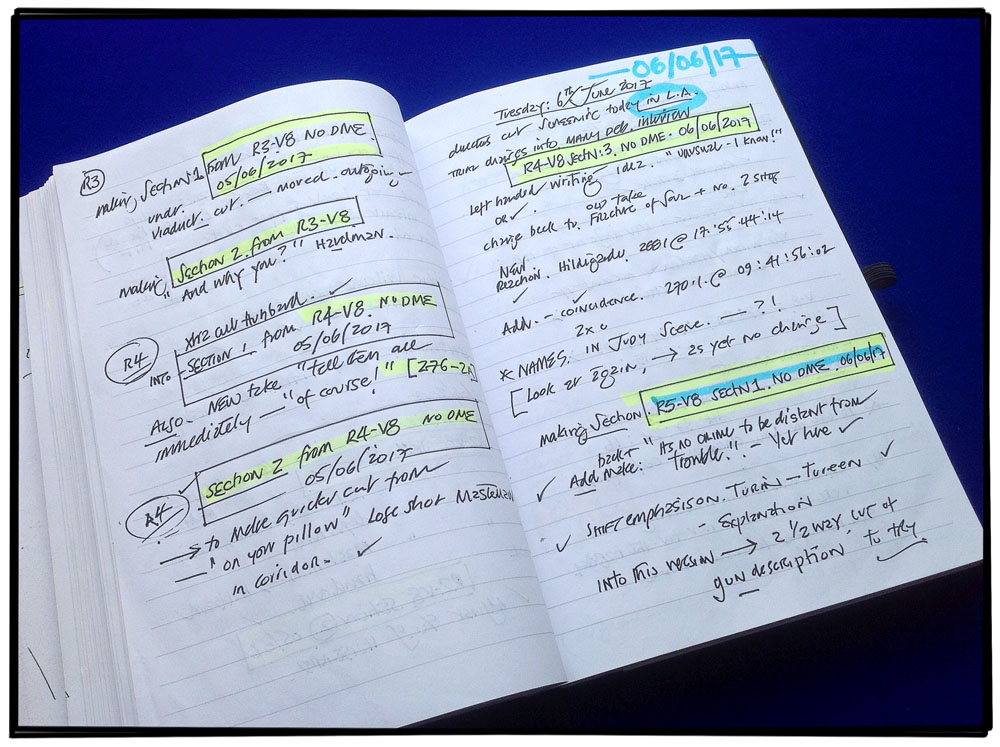

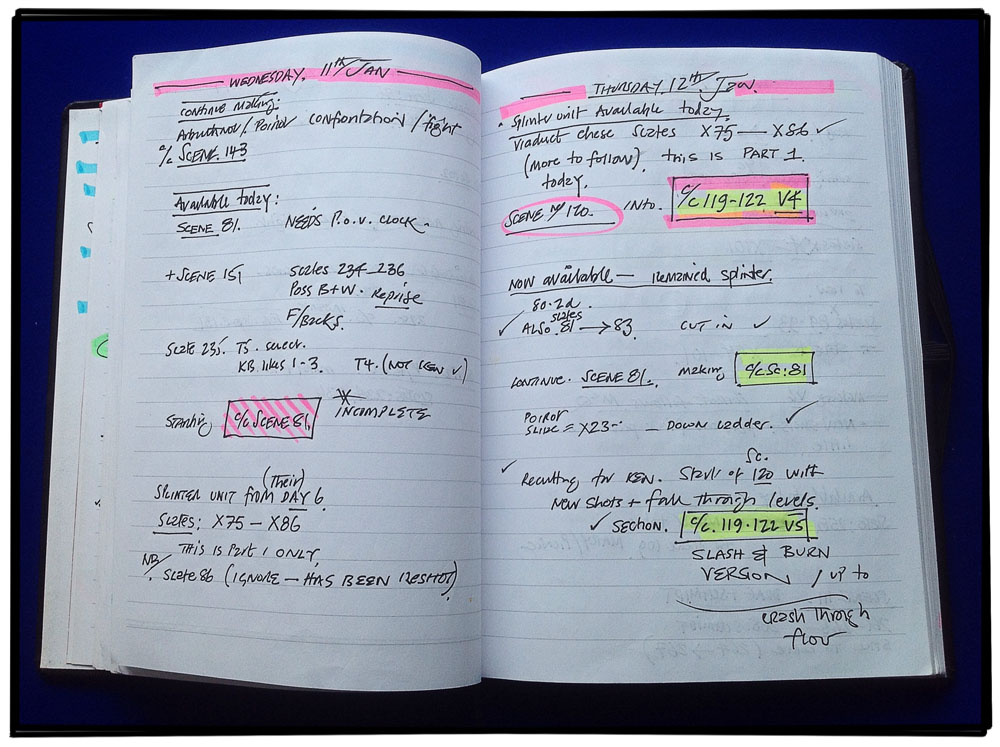

AUDSLEY: I have to keep a very careful diary of these things. In fact, this film is two diaries long. (Mick holds two diaries up to the Skype webcam.) This diary is like my day-to-day work and versions and all my notes about what comes in. It says here, that we set up on the 15th of November last year (2016). Actually, I had done a week before that in October because we shot some tests, which we entered into a little six-minute film. Ken shot on a stage and a small set to get make-up and hair and things like that, so we had done that prior to this pre-week, but we started shooting on the 18th of November.

HULLFISH: And how long did principal photography go?

AUDSLEY: I think it was about 15 or 16 weeks. There was a break for Christmas. The shoot finished in Malta. We were basically outside London for everything except the one week we did in Malta. They finished the end of the first week of March, and I had to put my editor’s cut up very quickly. The minute Ken get off the plane returning from Malta, I had the first cut up on the screen.

HULLFISH: That’s amazing that you were able to deliver that quickly.

AUDSLEY: Well I don’t know about the quality…

HULLFISH: One of the things I’ve talked about with a bunch of people, is the fact that it’s a process, right? You have to realize that things are going to evolve.

AUDSLEY: Ken (director, Kenneth Branagh) was new to me – but even with directors I’ve worked with countless years, every film is a unique experience. In this case, I had to make a relationship and you’ve got to get to know somebody: what their taste is, their understanding of the project – which may or may not be the same as yours – so adjusted accordingly and learn to deliver because time is always the enemy. I’ve been on this a year but it felt pretty rapid. But there were always deadlines to meet along the way: the first cut, the Director’s Cut presentation, the first preview, the second preview. There’s always a kind of deadline to meet with the film developing, in those periods between those events. So, in a way, you’re learning the film, but in this case, I was learning about Ken and why he wanted to do the film. It was a unique combination of his many, many talents. Him as an actor – the lead in this case – the star. Him as a director. And him as a producer. So there are many facets to that and there was a lot to learn about how that works best for him, including how to present to him, because he’s such a busy man, in the most efficient way. Because there aren’t many hours in the day if you’re doing three jobs. I find it pretty bad just doing mine. A man with more energy than Ken Branagh would be very hard to find on the planet. And my hat goes off to him. I’ll have to tell you a funny story about getting this job later.

HULLFISH: It’s an interesting point that he is both the director and star, among other things. I spoke to Kate Sanford about working with James Franco, who directed and starred in The Deuce on HBO, and she said that it was a little bit more of a challenge in picking performances and to get him to separate himself from being actor and director when judging his own performances. It’s a different thing when a director is making an opinion of someone else’s performances than it is their opinion of their own performance.

AUDSLEY: I was surprised and delighted that Ken had the ability to jump in and out of those roles effortlessly. Within seconds actually. He has a very good understanding of what he is putting up on the screen, so he could step outside the actor and become the director. He would literally be directly across the table in full costume, and he would give his fellow actors directions, in this case with a Belgian accent. But he seemed to do that effortlessly, which has my utmost admiration. He has some very good colleagues, friends, who he used to be a sounding board while he was on set: one of the directors he’s worked with in the theater, Rob Ashford, so it must be very useful to him to have somebody on the set who he can use as a sounding board. But that isn’t to weaken his decisive role. I think it was just so he could have a conversation. He was always very decisive about what he wanted and while he was shooting, because he was so busy, he gave me a very free hand with the material, which was great. I would choose what I felt free to choose and then offer it up for discussion. Many, many of those choices have remained intact because he was he was essentially happy with them. So we all try and help each other through the process.

HULLFISH: Absolutely. You were talking about being able to hear him on camera giving notes to other actors. When you listen to those, does that help you in the edit suite?

AUDSLEY: If I’m really honest, not. Obviously, it helps me in understanding what sort of conversations they’re having. I didn’t spend any time on the set in this film at all. I was too busy putting things together because when you’re receiving a huge amount of material every day from two cameras, it doesn’t seem appropriate unless asked to hang out down there. I’ve got a lot of work to do, and I would only go by if I was required or called, because the day is too short and digesting that much material in a day intelligently, takes all my energy. Even if I make wrong choices or choices which we update later, you’ve still got to be the first person to make a choice and present a scene as best you can and move the process forward. I think perhaps what I’ve learned over the years is that — you can’t call them mistakes — but if there are judgments which you update later on, you’ve got to be very clear about those choices at the beginning in order to have something there at all. You can’t be pulling your hair out saying, “I don’t know I don’t know which one is best.” You’ve got to make a choice and move on.

HULLFISH: That’s one of those things that I try to point out to my assistants: not to worry too much about that first cut. It’s a way to start a conversation and without the initial cut, you can’t even have a conversation.

AUDSLEY: Absolutely right. You’ll be amused by this, Steve, as an editor, but I always say to the students that I’ve been lucky enough to teach, or rather learn from, because you know that’s how it goes…

HULLFISH: Absolutely.

HULLFISH: Absolutely.

AUDSLEY: …The process of despair at what you make is very useful because if you have feelings that you’ve done something and you haven’t represented the material well, you have got an opinion and you move on. Use the despair to push yourself forward. Certainly in these months that we’re talking about – in January and February -putting this film together for the first time, you come in in the morning and look at what you did the day before and I think, “Oh my god. What am I doing? This is terrible.” And then you go to work and the next day you look at it again. And so it goes and eventually there’s something which you say, “Here’s my first version that I’ve just knocked it out.” But actually, it’s a week or two old.

HULLFISH: Somebody asked me what I learned from doing all these interviews. And it’s a stupid sounding point which is: editing is editing. In other words, you can’t just cut it once and you’re done. Like with writing, it is one thing to write and then the editing of the writing is another thing. Editing the first cut but the real work comes in what you do after that.

AUDSLEY: Yes. They’re all integral processes that are symbiotic and necessary. And you have to start with a foundation and move on. I would be willing to admit that the film that you see at a first cut – and that to me is one of the most Important moments – it’s where I see whether I’ve got a heartbeat of a film – and then you move on. But your thinking needs to be updated. It’s very rare that you look at a first cut and say, “Oh great! That’s it! Goodbye! Phone me later.” It doesn’t work like that. And of course, you’re surrounded by people who also want to develop the possibilities in the material. And there are other viewpoints. And then eventually there are audiences that tell you things by default or design, that can inform your real understanding of what you have communicated – when and how and to what degree of emphasis. And in this case, it was quite a fat script that we shot, and Ken was obliged to shoot all the pages as I understand it. And so the process of finding the correct narrative balances in the movie took us some time. And because it has the legacy of the Agatha Christie empire, we have to honor that. But also Ken needs to make an original-voiced film with his voice in it – literally and metaphorically. That took us some while. After Ken finished shooting, he saw the film very regularly. I think we were showing him probably once a week or maybe at least every 10 days. But we would also meet every morning and discuss reel-by-reel or scene-by-scene the detail of the development that we both felt was the way to go. But that was very private. There was just my very good assistant and associate editor, Pani Scott, who’s worked with me for seven years. It was just Ken, me and Pani, and we would talk it through and make notes and then present changes. In each case leading up to these key moments which, in the first case, was Ken’s director’s cut presentation to 20th Century Fox.

HULLFISH: You remember when that was?

AUDSLEY: I’ll have to look at my diary. You’ll be amused to know that they come in colors. My handwriting starts good and then slowly, as the months go on, it goes downhill. But basically there is a logic to this, for example, when the material’s coming in, and there’s so much and it’s so out of order, that I had discovered a few years ago that I would have to write down this note in my daily diary. This is what I’ve received. This is what it covers. This is the version that I’m making of a scene. I keep track of it very, very carefully so that if somebody says we had something better a week or two ago, I could go back. I found this was a protection against looking foolhardy by not remembering the billions of versions. But essentially it was just a log of what I had viewed that was coming in on a daily basis without particular notes or selections. It’s just a detailed account and you’d be amused because there are sometimes little doodles of exasperation. It generally comes with colors to make it look a little bit more fun.

HULLFISH: That’s awesome! I’m going to have to start an editing diary. I wonder if Moleskine will sponsor me?

HULLFISH: That’s awesome! I’m going to have to start an editing diary. I wonder if Moleskine will sponsor me?

AUDSLEY: This says, DCP, final mixes: so that’s tomorrow. But I can tell you, Steve, that I only arrived at these methods having made every mistake that was possible over the years. This was some form of psychological defense.

HULLFISH: You mentioned how private your initial screening was with Ken and that you were trying to be protective of Ken and protective of his material and give him a safe space to work. Can you expound on that?

AUDSLEY: I hope if he was here with me he would agree that we provided that. So about that safe environment, I do hope that is the case and Ken would agree with that. It feels to me that particularly in this case, because you’ve got an actor’s sensibility at work as well, Ken had three jobs rolled into one and that made it important that we all felt free to say what we felt about the material, what our ideas were and for him to feel happy to try anything through us to make things that he just wanted to explore while we had the time in the schedule – although time was always the enemy. We actually lost three weeks of time creating a collection of scenes for some journalists. We jokingly called it the spring collection. We started off with a 20-minute piece. Then we cut it down to six minutes. Then we had to dub it and grade it, so that took quite a bit of time out of the general long-term goal of getting to where we are literally tomorrow. But we were at the stage where that exploratory work needs to be done in depth in private before he decides what he’s going to present exactly. My analogy, Steve, would be that the cutting room is the place where you can make mistakes. It feels like home. You’ve got a shoulder to cry on. That I can make mistakes as well. I can try things. I can cut things out. I can do whatever without embarrassment. Of course, there is the contractual thing of 10 weeks which was honored of course… his DGA director’s cut time. The studio has been very very good to us on this film. I have to say.

HULLFISH: One of the things you mentioned early in our discussion that we have to get back to is the funny story about getting the job.

AUDSLEY: Ken and I had never worked together but my daughter, Marieke Audsley, is in the theatre business and she worked as an associate director on two of Ken’s plays which ran up to this project. So Marika, my oldest daughter, who had worked with Ken on these two projects running the show after the director, one of whom was Rob Ashford. So he knew my daughter very well through the theatre and then one day she said, “Dad, you’re going to get a phone call at 9:30.” At exactly nine twenty-nine and 20 seconds, the phone rang. And so I went and met Ken and he graciously offered me the job. The funny thing of all this being, when I found out that Ken was happy for me to do it, I said, “Well Ken, you’ve dropped me in it now, because I’m going to have to pay Marika 10 percent of my wages.” So far that is still negotiable. She was very revered by Ken and his colleagues and then I thought, “Oh my goodness, I’ve got to live up to this now! The shoe’s on the other foot.” I’ve got to be careful not to disgrace her.

HULLFISH: I’m sure you haven’t. Tell me about your approach.

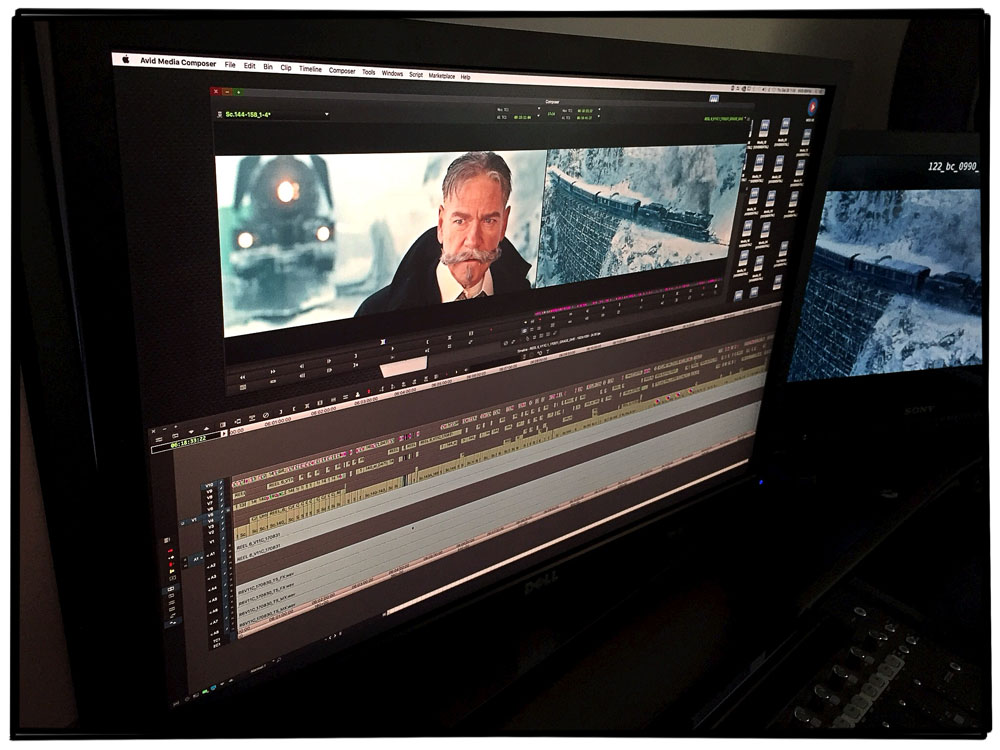

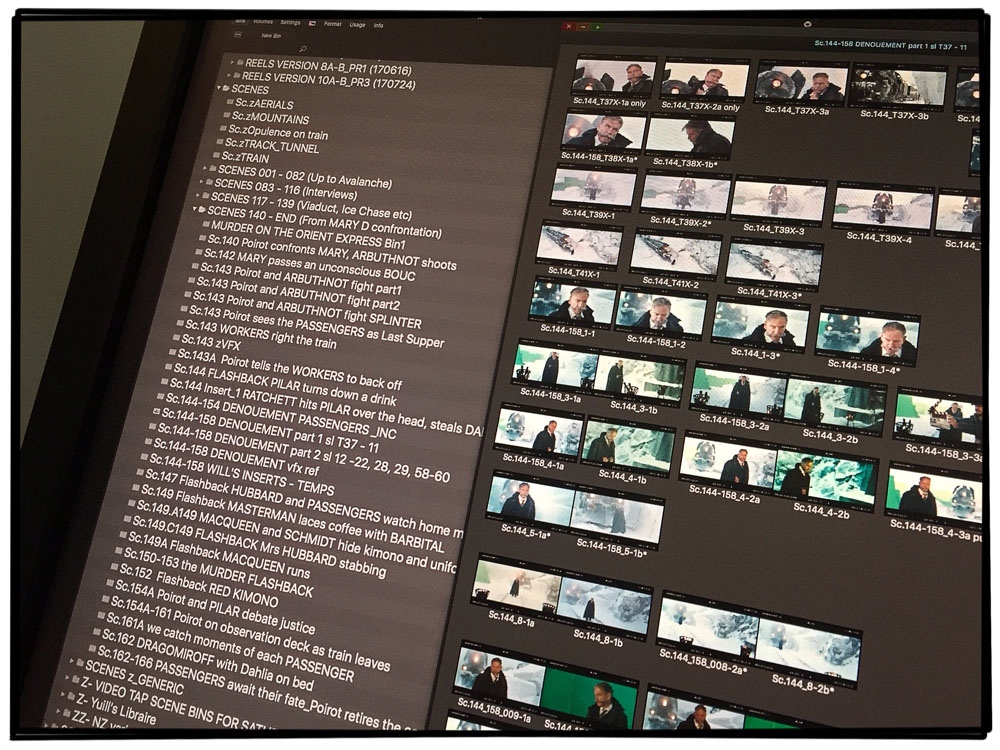

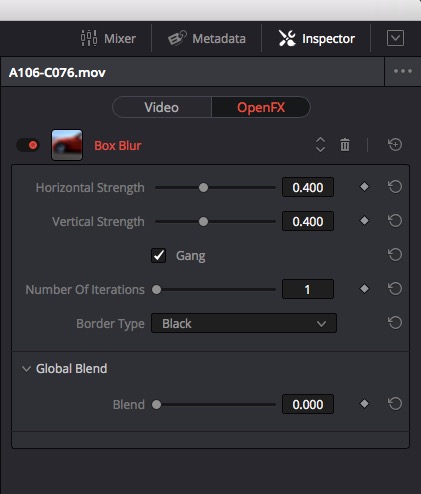

AUDSLEY: Steve, I grew up in the Moviola era. I know that dates me. And of course the interesting thing about this very privileged position which I’ve had, which is to span with both feet the digital revolution in film editing. Certainly in the Moviola days – which ended for me with 12 Monkeys – that was the last film I cut on film. In ’95 I think it would be. Of course the process, as you know, also was because film was what it was and the business of handling it. The preparation needed was was very acute. You had to prepare your material and learn it before you started very carefully. And of course, the amount of material we had then was comparatively small. I would say an average dailies load for me was half an hour. 25, 30 minutes. I remember thinking, “50 minutes? That’s a lot!” So I could look at that and study it in the morning and cut it in the afternoon pretty readily. That’s not the case anymore with digital cameras. I mean, in this case of Murder on the Orient Express, it’s 65 mil negative. But it’s scanned and effectively at that stage it’s as if it had come from a digital camera. So the quantities were quite, quite huge. Not the biggest I’ve had but it builds up as you know. So really the the process of preparing – I, in a way, still live in the Moviola age, although you can go in without a thought in your head and start constructing a scene. I used to mark up my own script with film because I needed to have a very controlled understanding of where to find it and what each piece was doing. Now of course I kind of do it in the same way, but I’ve made notes. I have a bin just of the material that is currently available for that scene. There might be four tiles (Avid thumbnails) or there might be a hundred and four. And I present all those and make notes about what each piece is and what it’s doing with the thumbnails and you go to work. Hopefully with an idea of what you think is important. And trying to remember where you think the film is going to be when you get to that bit. That’s the trick. Where you save time is trying to understand what the narrative is at that point. Even if you haven’t yet received it. That’s the tricky bit. But it is true to say, with the non-linear systems that we all use, that you can go in more unprepared than we could in the days where you had to slice it all together because you can undo it very quickly. And you can store the different versions and meld them together. I’m slightly old school in my prep. But obviously I’ve got the advantages that the non-linear systems and the speed with which you can literally think directly onto what you’re making and make adjustments all the time. So it’s like the alchemy or the chemistry of it is seductive and and it’s wonderful. Really it is wonderful. You could never have moved at the speed with which we do now, back with a Moviola.

HULLFISH: One of the things that I thought was really interesting That someone pointed out – who had made that transition from Moviola – is even the revisions took a lot longer because you couldn’t as easily save your old version if a director wanted to try something, then wanted to switch it back to the original cut, you had to disassemble one to do the other and you couldn’t just get back to your first cut.

AUDSLEY: We forget now because it is 20 plus years that that freedom allows the sorts of conversations which I’m hoping I’ve described to you accurately throughout this job. There was an anxiety I remember in the film days where you did think, “Oh if I have to take this bit out, that’s a couple of days work.” We did make dupe copies obviously. I often used to write down key numbers on the scene so if I had to change it, I had a record of it. Also, when you were getting instructions or performance changes or all that stuff it doesn’t feel like you’ve got to saw your own leg off.

HULLFISH: I am assuming you’re on Avid. Were you ever on Lightworks? That was bigger in the UK I think than in the States, though it definitely made in-roads early on.

AUDSLEY: Yes. That’s right. And it’s funny, I have a nostalgia for the shark (the logo on LightWorks) and the Avid. Funnily enough, about “12 Monkeys” when I met Terry to start that job we both were getting very excited about this LightWorks and a friend of mine – who’s no longer alive – a wonderful editor called Jim Clark, had just finished a film on it and he said, “Mick, you’ve got to try this! It was wonderful. Just what you guys need to do that film.” And yet we were actually prevented from using it because the technology wasn’t terribly stable and Universal inhibited us doing it, so we cut it on film. But by the time that we finished the film, everybody was using it and then LightWorks fell apart and Avid became the industry standard. Quite rightly, in my view. 2000 was my last LightWorks job, I think.

HULLFISH: I wanted to continue that discussion a little bit more of your process. You keep your diary. You use bins in Frame view. Do you use selects reels? Do you take notes in locators?

AUDSLEY: I tend to feel the best way is for me just to start and pick things which I feel represent the narrative idea that I think is the right emphasis and flow and then constantly update it. What I like to do is to make something, not look at it, put it away. Come in first thing in the morning and pretend I don’t know anything about it and usually throw my arms in the air with horror. And then start again. The great thing that we’ve just been discussing is this ability to update and change your thinking and look for things with the understanding that what you have done has given you. So, If you make something, it is pushing the project forward because you think, “Oh, that’s too strong or that’s not clear.” And so you have an eye, then to look through the material and say, “Oh, that belongs here, so I’ll use that.” So it’s the material speaking to itself in a way, or to you, and the chemistry and the sizes and the speed at which you choose to conduct it. That’s what informs you by doing it and by going along. Cut things and be prepared to make mistakes.

HULLFISH: You mentioned sizes, do you lay out your bins in a certain way that helps you navigate that easily?

HULLFISH: You mentioned sizes, do you lay out your bins in a certain way that helps you navigate that easily?

AUDSLEY: Generally Steve, in the UK we have this perverse way of numbering slating systems which has my American friends pulling their hair out. We just go numerically, so the shots come up in a numerical order. And I find that easier because I can just know that I got all the material appropriate for that scene because it’s numerically going up through the numbers. It’s usually quite clear what the sizes are. I make notes. Generally, everything has two cameras these days. So your notes might be just exactly what the B camera might be doing. So we use a different system than your A B C system.

HULLFISH: Describe that system for me if you would, because most American editors are used to 83a, 83b, 83c and so on.

AUDSLEY: Here each angle goes up numerically so it would start 100, 101, 102. So the number tells you that it’s a new size and set up. The takes come appropriate to that. So it would just be slate 100, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5. The preferred ones are two three four five, whatever. So it’s a chronological numerical system. For some reason that’s the European way of doing it. And I have used the American way, which I find very difficult because that’s attributed by scene numbers. Initially and then A B C as to which angle, then if you have A B C cameras that gets very confusing to me. It’s just whatever you’re used to, and I have edited with the American style, because I was fortunate enough this time last year to work as a second editor with Jeremiah O’Driscoll on the Allied film for Bob Zemeckis. And of course, then they use their own system even though they were here in London. And by the time Jeremiah got to the end of it, I think I’d learned his system and he probably learned mine. It was a heavenly job. I just thoroughly enjoyed it. And he’s great and we became very close friends in the process of making that film for the wonderful Bob Zemeckis.

HULLFISH: On the multi-cam stuff, which is of course, as you said, is everything nowadays, do you use in multi-cam mode? Do you edit with that so you can switch between cameras?

AUDSLEY: I prefer not to edit “in lock” as it were. I tend not to if I’m honest. I would only if it was dance or music related – sync related in the sense that you have to honor that timing for sync reasons. I prefer not to do it literally because somehow the value of each angle has its own statement to make. I may have to refer to it, but I don’t. I very, very rarely do that.

HULLFISH: A lot of people that I’ve talked to – in the bin they put the A camera and B camera in a row and then the Multicam after them. Someone I spoke to recently only cuts with multi-cam because it speeds up being able to switch the shot if the director wants the other angle.

AUDSLEY: When I cut on Allied, the work was presented that way… that was the odd request, but for my own reasons, I wouldn’t do it that way.

HULLFISH: How does Ken use the A and B camera? Does he shoot from the same direction capturing the same performer from two different sizes? Or does he cross shoot with opposing angles of two different performers?

AUDSLEY: I think we had everything of those possibilities because of the nature of the set. Obviously, in this case, a lot of it was inside a train carriage and we had these LED backgrounds which were great. They worked terribly well for the moving backgrounds. It meant that you could shoot two angles simultaneously and the backgrounds would correlate. Which was a hugely successful piece of planning inasmuch as if we’d had green-screens you wouldn’t have got all the interactive light on the table surfaces, on the glassware, on the China – all that stuff, because the LED was giving you the spill of the reflections of our background plates. So that worked terribly well. I don’t think there was a golden rule, Steve. The A camera was always leading the charge and the B camera would get whatever it could get without compromising the A camera angle. And if you’re lucky to get something from the B camera so be it.

HULLFISH: Do you find that one is easier to work with than the other — crossing or paired angle with different size?

AUDSLEY: Not to me. With Ken, some of the literal matching was important to him. so it was handy to know that you had a simultaneous moment shot from two cameras. To me, it’s just material and it all needs to be evaluated in its own right. But it’s great to have it if it hasn’t compromised the main angle.

HULLFISH: You’ve worked with many great directors. Have you found that they vary about how concerned they are with continuity? Are some more concerned than others? I’ve talked to Thelma Schoonmaker or Dody Dorn and they say, we don’t care anything about continuity. But I’ve worked with some directors and producers where continuity is critical to them.

AUDSLEY: Funny you should mention those two. I know both of them and I’d certainly say that I’m with them. There is obviously some mismatched continuity which distracts. But for me, if the performance joins things up, then whether the cigarette or the glass is up or down doesn’t matter. I once had a hilarious continuity error presented to me in rushes where a girl walks through a door with one jersey jumper on and came out the other side With a different one on. It was a very smooth cut and you’d look at it and you’d think, something a bit odd about that. I rather liked it but it did get re-shot, sadly. But it occurred to me that that was a wonderfully pure piece of cinema. Only in cinema can you do that. Discontinuity is kind of a poetry of cinema which I personally rather like. With Ken, in this movie, there were a few things where he wanted exact continuity. So, of course, we can provide that, but it wouldn’t be a leading factor in my mind. But for him, it was important as an actor and a director and we would absolutely honor that.

HULLFISH: Could you describe how these LEDs worked?

AUDSLEY: Basically it’s the modern version of the piece of paper rolling past the window. But it’s a huge LED image of film that we shot in this case in New Zealand of various backgrounds which was three or four cameras joined up so the window would appear to behave correctly. In principle, it’s a huge parabolic screen that surrounded both sides of our train carriage. And they could shoot both angles and get the background continuity as if you were traveling. And it was all shot in 65mm, so you’ll see it in very fine detail. We had an interesting production issue with this film, which was that the first few days of the shoot was the very end scene which Ken shot as a solo piece to the 12 very expensive actors who weren’t there. He did a whole performance to nothing. We just shot it one way and we only got the other angle two and a half months later. Then we shot the angles we needed of a very expensive cast, but with just stand ins. We worked out the angles we wanted and I cut that version and then amended the other end of it and eventually I got the actual players. We’re talking about Judi Dench, Michelle Pfeiffer, all the others all together but only for a very short time so we had to be very, very clear about what we needed from them. Because you can imagine getting those people together for any length of time. It was a production nightmare.

HULLFISH: You said you used to mark up your own script when you were cutting on film because you needed to have a very controlled understanding of where to find stuff and what each piece was doing. So how do you actually use the script and what do you put on it so that you are able to know better how to cut?

AUDSLEY: I didn’t do it on this project. Mainly because now with digital photography there is so much coverage that you wouldn’t be able to see the page after I marked it up.

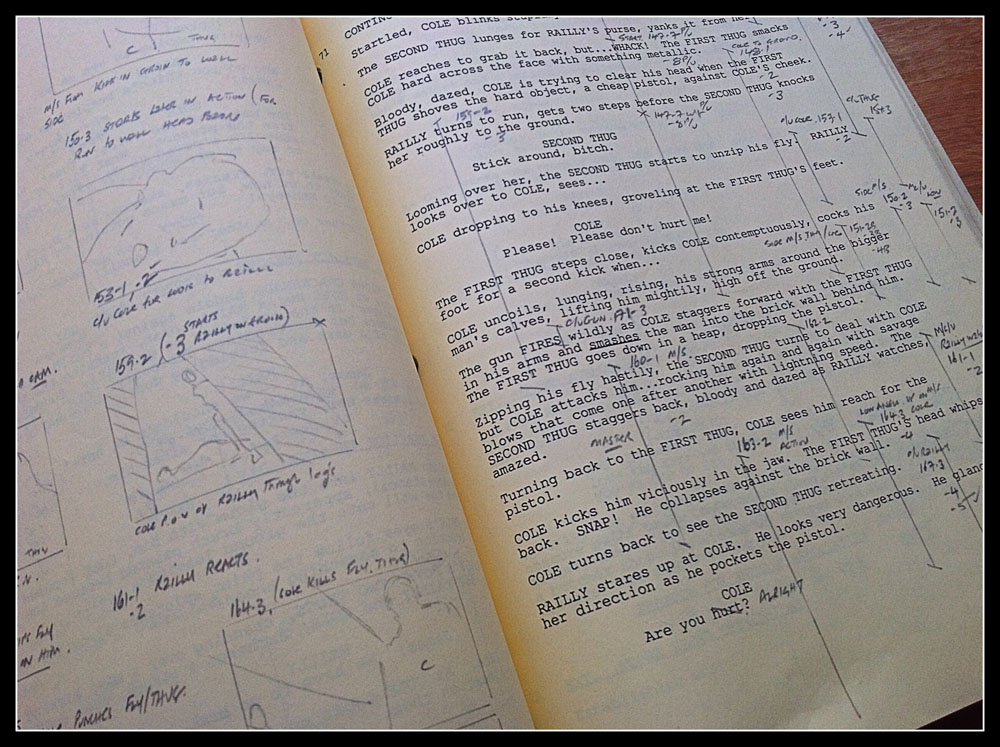

What I used to do was to mark each angle as a line north/south across the script as to what pieces it covered and what takes covered what so that I had an immediate visual understanding of the coverage throughout the scene.

HULLFISH: It sounds like you’re talking about a lined script. I’ve used lined scripts on most of my films, but usually, they’re produced by the script supervisor. Are you saying that you made your own lined scripts?

AUDSLEY: It’s a bit eccentric, I know, Steve, but it came from the fact that I found a way where I would take the lined script from the script supervisor, but then I would re-draw it for myself. I found the process was better because I could always put in more detail about what I needed. They seldom put the irregularities between the takes on the lined script. So if a take stopped halfway through, they often wouldn’t note that, so I would put a little cross next to it and say “Take four runs out here and hasn’t got the last three lines of the scene” or whatever. So this was a way of me learning what sizes the coverage I had and the irregularities between the takes and with some of the choices I would mark, “I’m going to go with this.” So it would get a double tick or something like that. The detailed notes that I take are important to me and I have to write everything down because my brain would explode otherwise.

HULLFISH: So it’s just a more detailed version of the script supervisors lined script?

AUDSLEY: Indeed. That’s exactly right. And I do find, Steve, that the process of doing it was a wonderful way of learning the material because it forced me to go through everything in detail – mark where it started; what I liked about it; where it stopped. Write that down on the page. I used to call it “the bible” and I would keep that as my bible so that when people said, “Oh is there another take of that?” or “Where does that go from there?” I could just go to that page in the screenplay and I’d say, “Well let me check.” And I could put my finger on it immediately. But that actually came out of the days when you had to have a control over the physical bits of film. Right now, with a thumbnail, I would know when that bit comes in. I would make a note of that in my diary saying, “Scene 65 covers these angles and numbers.” And then, in effect, that thumbnail was a pretty good representation of the beginnings of what I used to put in my lined script. But I just found the coverage was so much that it was physically impossible to write it all in on a piece of A4 screenplay. I can show you an example of that from a few years ago at the moment where I thought, “I’ve got to rethink this because I can’t read my own writing.”

AUDSLEY: Indeed. That’s exactly right. And I do find, Steve, that the process of doing it was a wonderful way of learning the material because it forced me to go through everything in detail – mark where it started; what I liked about it; where it stopped. Write that down on the page. I used to call it “the bible” and I would keep that as my bible so that when people said, “Oh is there another take of that?” or “Where does that go from there?” I could just go to that page in the screenplay and I’d say, “Well let me check.” And I could put my finger on it immediately. But that actually came out of the days when you had to have a control over the physical bits of film. Right now, with a thumbnail, I would know when that bit comes in. I would make a note of that in my diary saying, “Scene 65 covers these angles and numbers.” And then, in effect, that thumbnail was a pretty good representation of the beginnings of what I used to put in my lined script. But I just found the coverage was so much that it was physically impossible to write it all in on a piece of A4 screenplay. I can show you an example of that from a few years ago at the moment where I thought, “I’ve got to rethink this because I can’t read my own writing.”

HULLFISH: I’d love to see that inspirational bit of film history!

With your interest in using the lined script so heavily, did you ever consider Avid ScriptSync?

AUDSLEY: I never did use it. I know other people rave about it but I didn’t feel I needed it If I’m honest. And as I said, there was something about the process of forcing myself on a daily basis – when dailies are coming in – to learn the material in that way, even if I made wrong choices or what turned out to be a rotten choice. There’s something about that first private moment of learning the material which armed me or protected me during subsequent conversations and permutations of the material. It’s just something I personally needed in order to get the stuff in my head.

HULLFISH: Many editors do selects reels for that same reason: not necessarily to USE the selects reels, which of course they do, but it’s a way to learn the material, which is why they don’t assign the task to assistants.

AUDSLEY: For some reason selects reels always worried me a little bit – that once you took things out, it meant you left stuff behind, and I was worried that I’d miss something. And so I felt it was good always to go back always to everything as they were in the dailies. Maybe my reasons for making that selection were not now appropriate later on so I’ve found I tend to leave the bins intact. So it’s all there at your fingertips.

HULLFISH: Absolutely. My problem with selects reels — even though I use them — is because they take those select moments out of context.

AUDSLEY: Exactly. And I remember famously that Walter Murch said: that the days where you had to run down a reel (spool it on or off) were very useful because you had the pass the stuff that you may have rejected and you think, “Oh hold on a minute! Maybe that’s useful now.” And in a way, I’m trying to emulate that. Always keep your mind open to what you initially have rejected in order to understand it with new eyes.

HULLFISH: That’s a really critical insight, Mick. I’ve heard of guys doing this with full selects reels — not pieces, but taking the dailies and stringing them from end to end with even the slates still on and then running them in a monitor when they were thinking about something else or doing something else just so that maybe something new would catch their eye when their brains were working on something else.

Let’s talk about the structure of the film. Did it change much from the script?

AUDSLEY: A number of things did change actually. In the case of Murder on the Orient Express, there’s a very definite structure which is a journey and an investigation. There were some very clear chronological. structural tentpoles which had to be adhered to, but within them, we did move stuff around, and we did try different structures. One of them notably being the murder itself. It happens now in a different place from where it was written in the script.

It was written to have happened when the train was stationary but we made it happen while the train was still moving, before the avalanche. That was possible because we could change the activity in the windows to show that the train was moving. So that was quite a change but one that seemed to scream at us the minute we got the film put together.

HULLFISH: Those kind of things are so interesting to me because the scriptwriter wrote them for a good reason. People went through the development process with it in that spot and loved it. And you get to it and you’re really the first person to see that playing out in time which makes a difference.

AUDSLEY: Yeah and I think in this case, it comes from a much-loved novel. Perhaps where the murder happened was a legacy of the novel. We did obviously have to consult The Agatha Christie estate in everything that we did. And as far as I know, when they saw the film, which was fairly early on in the cutting process as I recollect, they were extremely supportive of the changes that we made. That was quite a big change.

Another interesting change which was an omission or a deletion: there was a premise of a backstory which was announced in the original writing at the beginning of the film and we ultimately dropped it in order to let it emerge in the fabric of the film later. largely because an event which wasn’t subjectively experienced by Hercule Poirot played by Ken seemed to be disembodied from the film and so we felt even as a prologue it didn’t carry the weight because it wasn’t experienced through him and he experiences everything else. So we removed it and let it emerge in the fabric of the film at an appropriate moment.

HULLFISH: You said that the movie screamed for you to move the murder scene. What was it that you felt?

AUDSLEY: When you have changes that work like that, you can never imagine why they were ever any different! I think in this case it just felt that the logic of the event happening after an exterior event i.e., in this case, the train being stopped by an avalanche, seemed less plausible. And so you wanted the murder to happen when things were normal. And then an obstruction comes which starts to unravel the process and be the narrative that we’re dealing with. So it just felt correct that it would unravel in that way.

HULLFISH: Do you remember the length of the first cut and what some of the choices were that you made to get it down to its final runtime?

AUDSLEY: It was about a hundred and twenty or thirty minutes as a first cut – as structured and honouring the script. Because of the nature of the film there are quite a number of interview scenes that were in the film “at length.” There was only one that we deleted entirely but there was compression, because of the build-up of the narrative, that allowed us to take shortcuts to reduce screen time. For those parts – in the back of our mind and unique to this film – it’s a star-studded cast and there had to be a balance, as best as we could, between your desire to just see those movie stars because we were very lucky to have such incredible cast. But at the same time not impede the momentum of the movie itself as it felt it needed to be.

HULLFISH: Two hours as an initial runtime for a first cut meant that you didn’t have to cut it down just because of time itself. So, it must have been more of a feeling that you needed to keep the story moving along.

AUDSLEY: Yeah. It found itself pretty quickly and then it breathed around the 115-116 mark to 120. And then it became clear to me that it wasn’t going to be a problem when we previewed the film first in late June in California. They always say a film could go faster, but it wasn’t like, “Oh, this is overly long to the degree that we couldn’t cope with it.”

I did try and make a lean first cut. If I can, I’d rather omit something than just have the difficulty of trying to figure out what the movie is from four or five hours. I know other people like to do it that way but I prefer to try and get it quite tight quite quickly and then discover if – in the process of doing that – that we’ve damaged it or omitted something or the emphasis is skewed in the wrong direction. We didn’t have those problems with this. We just had a difficult balancing act between the content and the fun of those big stars on the screen.

HULLFISH: What do you look for in an assistant editor?

AUDSLEY: I’m incredibly privileged to have Pani Scott, who’s been an assistant to me for years and who definitely deserves the title she has got on this film, which I insisted that she have on this film as an associate editor. It’s somebody who takes all the headache of the practical side off your hands completely which she has done for me for nearly 10 years now – miraculously and seemingly effortlessly. But also she has to be entirely inside the cutting of the film and with a very strong opinion because they’ve got to watch everything and understand it. And so we had lengthy discussions as equals about what we think is good or relevant to this film.

I find it very helpful to have a sounding board in that way because the sheer volume of material we’ve got to deal with these days is overwhelming. She fulfills those roles admirably and is a fine editor in her own right.

After all these years I have my own methods of my own eccentricities and sensibilities as a filmmaker and she’s very gracious about understanding those. But I know how unique that is and in this case, she worked also a lot with Ken when I was busy with one thing she would be taking notes on another. And so it’s a very close working relationship in that way. It’s a lot to ask people because the job is highly technical and I haven’t got my head around that at all because it’s all changing so fast. There’s a mountain of stuff on a daily basis to manage and she frees me up to be able to just sit there and make the movie which is a great privilege.

HULLFISH: I know this seems like a very obvious question and perhaps one that’s difficult to answer but: How, as an editor, are you the storyteller behind the film? Does a cut affect the story?

AUDSLEY: Profoundly. In terms of articulating a narrative in a way which engages the audience fully and lets them get lost in it. You know as well as I that we can only put up there what we’ve been given. But we are conductors: like an orchestra. And you can play in tune or you can play out of tune. You can play too slow; you play too fast. You’ve got to understand when information is landing or when it’s not. So all these factors are the articulation of the narrative.

I strongly believe – how could I not – that the editorial contribution is undervalued. But it is a harmony. It’s a close, close relationship with the original writing of words on a page. Some of my closest friends have been writers on the projects I’ve been involved with. And it’s how we symbiotically get the movie to work and get it across. So for me, it’s very, very important that editing is the articulation of that narrative.

Sometimes we shield the audience from weak writing or weak performances to a degree but not entirely. Sometimes the contribution is profound. Sometimes it’s perhaps less noticeable. It varies on all projects to varying degrees. Of course I think if you are as passionate as we all are about the craft of sticking films together then you feel very strongly that you have an ownership and a responsibility of it to get the best from what you’ve been given and it is a bit like being a midwife you give birth to it and then, of course, it grows up and leaves you. I am a big proponent of the editorial process being a second stage of writing or it’s perhaps the third stage – and that we are writers in the cinematic language. And the best writers I know are the ones who use pictures rather than words wherever they can. Sandy McKendrick famously said: “A film should be 70 percent comprehensible with the sound turned off.”

HULLFISH: Otherwise it’s not cinematic.

AUDSLEY: Exactly. Exactly. And the cinematic language and the process that we go through obviously is always to try and whittle down things to the bare bones in order that they suddenly gain a power and a direct connection between what you’re showing and the audience’s stomachs. When it works it’s heaven.

HULLFISH: You had some pretty amazing actors a great cast. Talk to me a more about choosing performance and about shaping performance.

AUDSLEY: Well I was lucky that Ken – with his own performances – certainly gave me free reign to choose what I thought was appropriate in my first passes and offer it up. That was something I took very seriously. But at the same time, you have to rely on your gut responses to things because that’s how we make a living. You’re hired for those responses. If you say, “Oh, I don’t think HE’D like that.” you’re dead. You’ve got to go through what YOU want to make first and then offer it up for discussion and then perhaps be guided. We didn’t change performances hugely at all. We just kept on mining what was there together; refining it.

Shaping the performances: Occasionally we would say, “Perhaps my original choices were a little bit one colour than another. If there is a slightly different colour to be had Let’s go for that.” It was just a sort of a discussion that we had throughout the post period. Shaping performances. I never felt that I didn’t have what I needed. It was new to me to have somebody whose performances I was choosing be my immediate boss. And he’s very good at standing outside of his performance. I was staggered from very early on of how Ken has the ability to have an opinion as an outsider of his own performance which I find a remarkable ability. And so when I learnt that by just working together that helped me relax a bit. And I learnt a lot from him as well because he could tell me thinking stuff that was going on inside his head. We would share a dialogue about it.

HULLFISH: The funny thing with working with a director who is also an actor in the film — and I’ve been there, so I sympathize — is that editors are used to being very critical of performances in a kind of brusk, matter of fact way, and when the person who did the acting is sitting behind you, it can be very uncomfortable.

AUDSLEY: Yeah. One has to come up with a language which is also not dismissive or hurtful about why you have rejected something you don’t say, “Oh, it’s not that this is bad, it’s just not doing THIS for me.”

An interesting thing: the first film that I did with Stephen Frears – which starred Ian McKellan -in a film for TV many years ago called Walter – it was magnificent actually, but it was my first collaboration with Stephen Frears and we were shooting in a disused hospital in Northern London in the winter in February and my room was the only one that was warm. Ian used to come and sit in my room when he was waiting to be called. He said, “Do you mind?” And at first, I was very conspicuous. These are the giants of British acting! So, I told him I wasn’ a bit embarrassed and nervous and he said, “Don’t be. Just tell me what’s going on in your head.” So I started explaining out loud – which I never do or have done since – and I’d say, “Well, I’m choosing this because of the eyes doing this here and that because of that lighting and here you get up a little bit quicker…” and I went through all that sort of stuff about why I was making choices and he was extremely gracious about it. He never interfered. He just said, “Oh well that’s absolutely fascinating. Thank you so much I’ve learnt a lot.” This was Ian McKellan! That was in 1981, I think. I was back in the same position working with Ken, you know, a giant actor was sitting in my room next to me.

HULLFISH: You’ve edited for Frears many times.

AUDSLEY: Many times many many. I think there’s something like 20 films.

HULLFISH: The other guys that keep coming back to work with you time and time again are Mike Newell and John Madden and, of course, Terry Gilliam. Is there anything different between when you work with those four guys and when you’re working with a new direction you’ve never worked with?

AUDSLEY: I think I first worked with Mike Newell in ’84. I met him through Stephen. Mike asked me to do a film called Dance With A Stranger which is a magnificent film. Of course, people you’ve known for 10, 15 years, 20 years – or have friends in common – means that you have an understanding before you go to work and sort of trust. And of course, working with new people – which is what I’ve done in the last three years – slightly by choice – it’s good to expand into new personalities.

I realized when I started work with Baltasar Kormakur on Everest that I had to make a relationship from scratch. And that was true also working with Ken. Same with my part in Allied with Bob Zemeckis. These are people I look up to greatly, but we don’t have a history together. I have to just kind of make a trust whereas actually people like Neil and Terry I have known for so long here in Britain it just felt like family.

HULLFISH: And that trust is really important because editing is such a process right? You talked about how much some of your early cuts are not really things you’re proud of. So in that editor/director relationship, you need to say, “OK it’s bad right now but I know Mick’s going to get this into a place where it needs to be.” Those four main directors know that because they’ve had so much experience with you but when it’s somebody new….

AUDSLEY: You still feel terrible though… As much from a performer’s point of view Steve, that used to keep me awake at night thinking, “Have I represented their work intelligently?” In my teaching with students, I’ve tried to let the young editors or more inexperienced editors be aware that we all feel that and it’s a useful feeling to have to be despairing of what you produce. It means you’ve got an opinion and you can move on and it gives you a way of looking at what you feel it should be and how to find that in the material or the way you articulate it. I don’t think that ever goes that way even after all these forty-five years or whatever it is I’ve been doing this work. It’s a sense of: is this good? Is this right for everybody?

HULLFISH: What temp music did you use? When did you add it in the process? What are some of your thoughts about temping?

AUDSLEY: Temping is a tricky one isn’t it? In general left to my own devices, Steve, because I’m old school, I prefer not to put music in until I understand the cut and the structure of that movie because it makes things look a lot more confident than perhaps they should be early on. And I’d rather deal with any issues – to do structural storytelling or narrative or what’s in or what’s out – without the support or help of music because I know it’s only going to get better and it sometimes hides issues. So, for my own personal work, I would leave it very late.

In this case, we did put stuff on quite early because Ken liked to have music on. And so we did temp with choices of my own initially, and then with two very skilled music editors. I would give them a cut and they would come back with thoughts and ideas. And that was a conversation that would go around between them and Ken directly while I was carrying on building the film.

I think what we noticed now in this current climate of filmmaking is people feel a greater need to show early incarnations of the scenes or reels or the whole movie with a lot of support from music. And I only like to put it there as late as I can. It’s just my preference from the days where you couldn’t put multi-track audio into your cut. Right? But I accept it. And it’s just the way it is now. It can be very helpful. But I find it’s often not quite right and it can confuse you because it giving you a colouring too early before you fully realize the colouring the scene might have. So an additional blanket makes you feel it looks great. But it might not be telling the story quite the way you want yet. That’s my major worry.

My friend Terry Gilliam showed me a cut of his Don Quixote film which he’s working on at the moment and he was apologizing about the sound and the VFX weren’t in there and that there was no temp music yet…. I said, “Terry, look I’m way beyond all that. I just look at the heart of the film. I know what goes on afterward that’s fine.” I’m happy that it was like that.

HULLFISH: But that’s hard for other people. Do you remember specific soundtracks or composers that you temped with?

AUDSLEY: Our composer was Patrick Doyle and so we tried to use as much of Pat’s own music because he always collaborates with Ken. So we tried to exploit scores that Pat had done prior. I think we strayed from that in the end, but we weren’t using Thomas Newman, for example.

HULLFISH: No Hans Zimmer.

AUDSLEY: We didn’t use any Hans or Thomas. We used mainly Pat from previous scores. To be fair to Pat, he started to give us some pretty good demos which he worked on while we were cutting. We did use a famous piece of Arvo Part piano music which is quite well known: “Spiegel Im spiegel” as a guide for one area. It was helpful for a while, but eventually got replaced by Pat.

HULLFISH: So a final question about design and how much does it inform or affect your picture cut?

AUDSLEY: I think it informs it a lot. I like to think that we work in collaboration with each other on that. They’ve done a beautiful job on this film. I can say that the sound design is spectacularly good. James Mather, and the dubbing mixer, Mike Presswood Smith, who’s a very old friend of mine – they and their teams have done absolutely beautiful work.

What we tried to do is have a conversation where I give them the cut and I want to hear what they’ve got to say about the movie editorially and the way the movie is working. Then we talk about the sound design and when they’re mixing they come to me and say, “Well what do you think of all this? What do you think of the sound?” But we try and make it that we’re all making the MOVIE and THEN our particular specialization. I want to hear everything. I feel we’re filmmakers first and THEN we do the disciplines that we specialize in.

HULLFISH: And are you doing any of the temping of sound design?

AUDSLEY: Yes. In this case, James Mather, the sound designer, gave me effects to play with in my cut. Obviously, they’re rudimentary compared to what we end up with in Dolby ATMOS. But he gave me material to work In this case there was just a practical need to just smooth out the tracks and have the train sounding like it was traveling when it wasn’t in fact. I like to try and design the placement of those things very carefully myself and then they embellish and expand on them and come up with their own thoughts because. I firmly believe that the architecture of the sound informs the picture greatly and vice versa.

HULLFISH: So I’m assuming you cut picture first you add some sound effects and then you find that you need to adjust trims or pacing or something based on sound effects edit?

AUDSLEY: Yes absolutely. We would make adjustments as we go along. I would say, “Oh hold on. Do you want a bit more time there? That looks a bit cramped to me now that we have all those sound effects in.” It’s like a conversation: getting the film to breathe in and out together. Or maybe there’s a sound that you want where an image can help sell it. It’s very much a dialogue between us.

HULLFISH: You’ve been so informative and generous, which I know is part of your ethos, because you’ve got this project you run with your wife and daughters: Sprocket Rocket SoHo. Can you tell me a bit about why you started that?

AUDSLEY: It’s really about bringing filmmakers together in a way in which we are talking now. And that’s very important to us. About four or five years ago I became aware that the digital age of moviemaking as opposed to what I came from which was Moviola’s and all the rest of it Twenty five years ago. I felt that whereas I had been a beneficiary of and hopefully was able to give apprenticeship and learning to people by sharing. The doors were much more open. You had assistant editors who were with an editor and a director in the cutting room and they would be handing trims and they would have opinions and there was an apprenticeship system there. The digital process means I’m in a room on my own and my assistant’s in a room on their own and so we weren’t talking to each other anymore.

So about four or five years ago with some close friends of mine who supply my equipment, we said, “Well let’s just get people together in a room and throw some alcohol in and bring people together.” We had such an extraordinary response to that. Not just cutting room people, but directors or young students sound designers producers, anybody that wanted to come and meet and talk about making movies and it was a big success. So what we have done – with my wife, who also used to be an editor, and we actually cut many films together years ago, and my daughter – we bring people together for usually a panel discussion on a topic and then allow people to come along to network and have a drink and talk and have a chance to exchange ideas with everybody from different ages and disciplines. And it seems to have been enormously successful.

Our problem is we need funding. You need money. Dolby has been very good to us allowing us to use their premiere viewing theatre which has been great as a venue. Avid have given us some help. I’m involved with a university course here in England and they’ve pitched in, but we struggle to make ends meet, because we’re not a big company. We’re just three individuals who are trying to give something back to the film business.

Our problem is we need funding. You need money. Dolby has been very good to us allowing us to use their premiere viewing theatre which has been great as a venue. Avid have given us some help. I’m involved with a university course here in England and they’ve pitched in, but we struggle to make ends meet, because we’re not a big company. We’re just three individuals who are trying to give something back to the film business.

The website is also filled with beautiful little interviews. For example, Bob Zemeckis gave me a great interview. We call them Tips from the Top; little five minute things. They’re not ostensibly to make money but a website has to be paid for.

I really hope you’ll register, Steve. It doesn’t cost anything, because we didn’t want a cost for registering. Obviously, our events are largely in London but I’ve had friends in LA who said, “Will you come here and set something up like that? Or would you do one in New York?” We just haven’t got the funding.

Now that I’m off this film, we’ll be planning some more videos and some more evenings. We do about four a year four because we find that’s quite a lot.

HULLFISH: I know how you feel. I founded the Chicago Avid Users Group back in the early 90s and it’s a lot of work to program and schedule and try to fund and find a venue for. I applaud you for your effort.

AUDSLEY: Well, then you know. We found that by being a little family business was kind of what people liked about we’re not an organization or a company we’re just filmmakers who want to bring other filmmakers together.

HULLFISH: I love that idea. So for people who are interested, they can visit: www.sprocketrocketsoho.com.

AUDSLEY: Well that’s why it’s been such a pleasure to talk to you, Steve, because it’s nice being interviewed by somebody who’s also a film editor. If you happen to be in London, come to one of the events which I would very much like if it was possible. Steve, thank you. It’s a great pleasure. It’s an honour. Art of the Cut is terrific. And I feel proud to be a part of it. With friends like Joe Walker and all that, I’m privileged to be up there with dear old Joe and people of that calibre. So thank you for having me.

HULLFISH: It was wonderful having you on Art of the Cut. Really great talking to you, Mick.

AUDSLEY: Keep in touch.

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish

The first 50 interviews in the series provided the material for the book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV Editors.” This is a unique book that breaks down interviews with many of the world’s best editors and organizes it into a virtual roundtable discussion centering on the topics editors care about. It is a powerful tool for experienced and aspiring editors alike. Cinemontage and CinemaEditor magazine both gave it rave reviews. No other book provides the breadth of opinion and experience. Combined, the editors featured in the book have edited for over 1,000 years on many of the most iconic, critically acclaimed and biggest box office hits in the history of cinema.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now