(Normally I am careful to clear all photographs and image in my articles, being careful to credit photographers and copyright holders when necessary. In this article, most images are pulled from the internet. If you own the rights to one of these images and wish me to pull it or credit it, let me know.)

HULLFISH: Was the last thing you cut a documentary? Or have you cut any documentaries?

HEIM: I have but the last thing I edited was a film about Hank Williams about a year and a half ago (I Saw the Light) which I had a great time on actually. It was picked up by a distributing company sight unseen which is very unusual. From the beginning, I said the cut is too long. I was hired late because the original editor never started the film due to an injury, but by that time it was five weeks into the production and I was way behind. They finished shooting around Christmas and I finished and I called the director and I said I think the film is really terrific but it’s three hours and 20 minutes long. He said, “no problem.” Well, we never got it short enough and it’s partly the pacing. I know a lot of people who saw it and really thought it was wonderful. On the other hand people say it was too long. So we finally went back into the cutting room and took out about 10 minutes which was not enough but it was a lovely movie, and if that’s going to be my last movie, I don’t mind at all.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6bKjhqvbHs8

HULLFISH: One of things that brings up to me is the social engineering aspect of being an editor. How do you deal with the director in knowing when to push harder or to know that you can’t push too hard?

HEIM: Don’t get me started.

HULLFISH: The whole point of this interview is to get you started.

HEIM: (laughs) One of the things you have to realize about being an editor is it’s two thirds psychological, maybe more. You are between the director’s vision and idea of what he shot and what he really shot. You are the conscience of the director in a way. So there’s no point in being dishonest with directors because two things will happen: They’ll either dismiss you – I don’t mean “get fired” but they’ll just not listen, or it’ll just start off on a nasty foot. So you just try and protect the director.

Look, I don’t want to seem particularly vain about it because I don’t have the right answer half the time either, but the director usually thinks that they’ve got it. They’ve nailed the shot. They’ve nailed the scene. And they often don’t. And to be able to turn the director and let him see your vision is incredibly important.

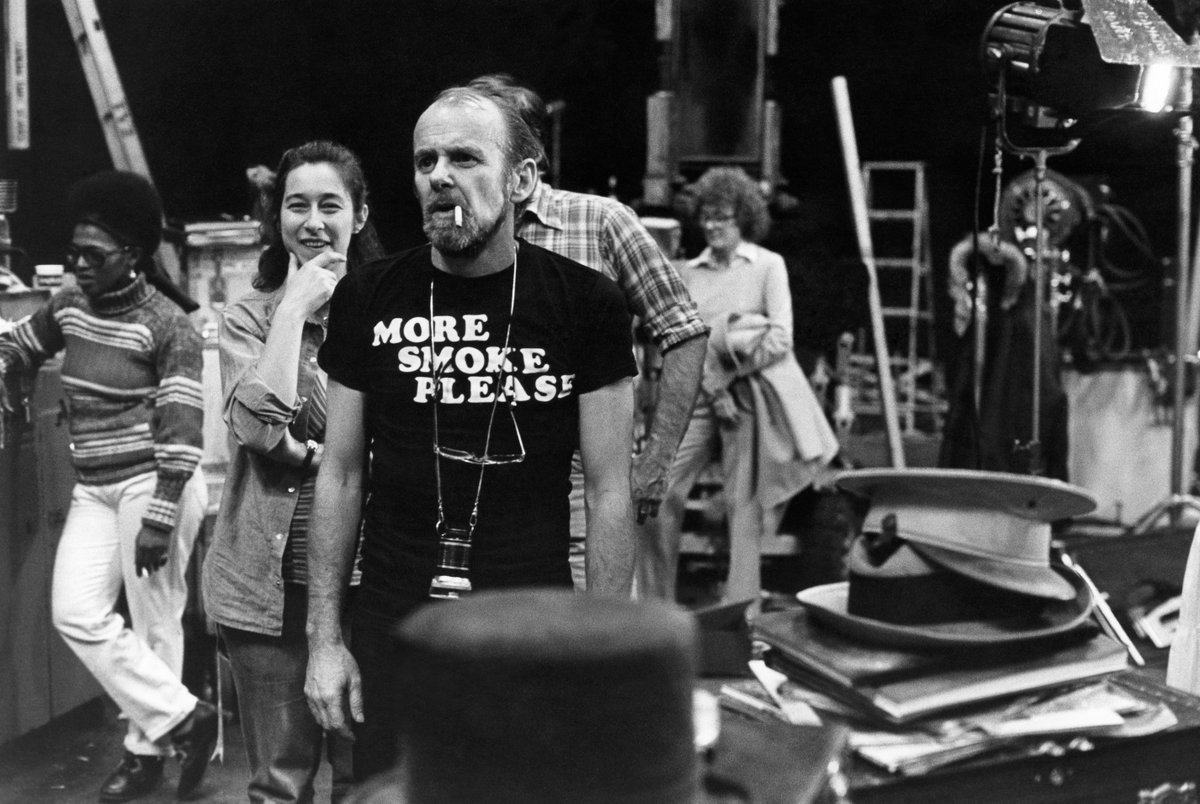

Fosse (director, Bob Fosse) referred to me as his collaborator and I think that’s just the best compliment coming from a guy like Fosse.

He also said I was his conscience because everybody wants to get that last little frame of what they think is wonderful, but maybe it’s the frame before.

As an editor, you have to be kind of neutral. You have to be a neutral observer. You have to protect the material. You have to protect the actors and sometimes you have to protect the director from his own instinct, or from the producer. That’s a situation that can be unpleasant.

HULLFISH: I haven’t had that problem before. Sounds like a precarious position.

I was cutting a pilot and a friend was down the hall cutting a series for HBO and I walked by her room and I see a couple of three people outside the suite in suits. It’s cliche but they were… and I poked my head in and said, “So are you getting a lot of notes?” And she said, “I told them the other day that if they are going to give me notes they have to go outside the room write down the notes.”

I was on a movie called Grey Gardens – we were ready to show the film to the head of the studio – Colin Callendar – and Colin was not available so our producers kept sending this stuff back up to HBO for notes, but there was no way the people at HBO had the authority to give notes so at a certain point, I said, “I really don’t want to fight with this anymore.” and Lee Percy came on and he finished it and we had a shared credit. I think Lee’s finished two movies that I started on… maybe the other way around. Notes: Sometimes they’re good and sometimes they’re bad.

HULLFISH: You mentioned screenings, and sometimes the notes from them can be strange from audience members, but there’s a tremendous value to just being in the screening and feeling things in a different way with a real audience, right?

So we had this meeting and the director, Patrick Kelly, who was well over six feet tall and enormous. He is the kind of guy who wears sandals in the winter, you know, an American flag bandana down around his head, very tall. And Chartoff was a very tall thin man and Chartoff was sitting next to me at the screening and the audience absolutely loved the movie for about 50 minutes maybe an hour and Chartoff, every time there was a big laugh, he would give me a shot in the ribs, which I probably still have bruises from. And he would say, “See?” and I would say, “Wait.” And at the end of the movie we all wanted to crawl out of the theater. Two of the screening cards – which I kept for a long time – somebody had added an extra column after good, fair, poor: they’d added “shit” and checked it off all the way down.

On another card, the card asked: “What did you learn from this movie?” – It was a comedy for God’s sake – and somebody wrote: “Don’t ever take free tickets to a movie.”

HULLFISH: OK, let’s go a little more highbrow. Let’s talk All that Jazz. I was talking to Dody Dorn about how much she loved the famous pencil snap with no sound as – spoiler alert – as the Joe Gideon character has a heart attack. Can you talk me through that?

HEIM

All the actors sitting around doing the table read, they were being cued to laugh. And it wasn’t very good so Bob got in a comic for the second day of shooting. Everything took a long time on that movie. Bob got in a comic and that guy was actually telling jokes and that didn’t work either. And it just seemed like we had a laugh track going and it didn’t seem right. So at some point, and it was probably Fosse’s idea, but I probably started to fade out the track. So we just took it all out and we put in the loud sounds but they’re the kind of sounds you would hear when you’re having a panic attack. Sometimes you don’t hear anything, and sometimes putting out a cigarette sounds like gunshots. Cracking the pencil was like that too, it just worked. So we left it like that.

When I worked with Fosse when he came into the cutting room we would re-work scenes and we never put them down until we were happy with them. Later, when we had the whole picture, we might go back and do a couple little things, but every scene we tried to polish as much as possible to get the most out of it. Which is why I was on some films for 14 months with him. Every day was an adventure, absolutely every day.

HULLFISH: I wrote an essay about how – with pacing and rhythm – we can learn from other arts and Fosse was obviously a dance guy so did you have a common language of rhythm and pace? Is that overthinking it?

HEIM: A film I did after All That Jazz was called The Fan, with Lauren Bacall. I met the director and we had a nice talk. Everybody thought he was way over his head. A commercial director, who became much better later. First day of dailies, they were cripplingly slow. it’s an epistolary novel that takes a form of letters that the guy who writes to this stage star that he’s obsessed with.

So we have him on the steps of his tenement in Manhattan and he’s reading a letter and he’s actually reading the letter, and it’s deadly dull. At the end of watching dailies the crew did something I’d never seen before. They all applauded, but I didn’t applaud. So he turned to me and said, “How come you didn’t applaud?” and I said, “It’s very slow and I’m really very worried about that.” And he said, “I come out of commercials I can get everything down to 60 seconds.” I said, “This is a movie. You’ve got to get it to 90 minutes.”

After that he didn’t trust me at all until I showed him a couple of cut scenes and he said, “Oh, I see what you were talking about.” And he started to pick up the pace of the movie and we were able to beat that down. That might’ve have been the worst thing I ever said to a director.

HULLFISH: How do you get that beat down to a proper pace? A lot of people say that a movie has its own rhythm, so what do you do if the rhythm is that slow and it shouldn’t be?

HEIM: I know what you mean. Back in New York we used to say that the actors talk too slow. Movies of the 30s and 40s people talked fast as hell. And they filmed 70 to 80 minutes long and they stepped on each others lines, but it was rehearsed and it was crisp, and you might not like it but it moved things forward.

Then there was a period when the actors – and directors – tended to be kind of indulgent. You can’t make the actors talk faster. I discovered that you can basically take a love scene, and if you overlap the dialogue, it seems like an argument. That’s not a great trick but I’ve done it – or close to it – when I want to pick up pace.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=paf-0zsOAdg

I loved working with Nick Cassavetes because he would go over with the actors and say, “Stop acting. Just know your lines and be fast between takes.” So we would tighten the hell out of it. A film I did with Cassavetes was The Other Woman. If you look at it closely you’ll see that that Cameron Diaz is out of sync a lot. Because we just cut her words together. She and Nick did not get along, and Nick and I both felt we just want to make it better. And if she doesn’t know her lines when she comes on the set let’s just make her say the lines so we cut around it. Those films are really tight cutting. It’s hard to do. If the actors are slow, you just get stuck.

I love molding the performances. That’s the raw material. I look for the best takes and I try very hard to protect the actor’s integrity. I look at dailies first. By noon I’m usually looking at the dailies and I will know which takes I want to use. And then if I sat down with the director in the evening and he didn’t like any of the takes that I liked, then I knew that means trouble down the line. I would always use the best take in my mind that the actor has done. And sometimes the director would say, “Why did you use that one? Why didn’t you use this?”

When I was a sound effects editor, an editor named Aram Avakian (who edited Mickey One) was a brilliant editor and had a great visual sense. He was very smart. I was working as a sound editor on The Group and he came up behind me, and it was a dinner scene of two people talking, and he said, “That’s a great cut.” I turned to him and asked, “Why is that a great cut?” And he said, “Because it just seemed like two people talking. Look at it again.” So, I rolled it back and forth and I told him I didn’t see it. He says, “Look at where the direction of the fork is now and then when you cut you come back and you move the other way.” And suddenly I learned all I ever had to know about physical editing. It was kind of amazing because I never thought of that. The motion from one carried over into the next take. It can’t always happen, but when it does it is thrilling.

HULLFISH: You said one of the things about cutting musical scenes was to try to have the flow of the motion of one shot lead the audience’s eye to the next cut.

HEIM

Paul Taylor, the modern dancer and terrific choreographer had specials on PBS. Somewhere he learned the idea that movement should go from one shot to the next. Most specials you don’t see that. He’s got dancers running around the stage like crazy but there’s always a flow. I found it thrilling.

I met Fosse back in New York. I was doing a lot of television as a sounds effects editor and I’ve done a little bit of picture cutting, and I got a call from a guy named Kenny Ott. He was a well-known line producer in New York, and he asked me if I’d be interested in working on a TV show with Bob Fosse and Liza Minnelli. I said “sure.” So I went up to meet Fosse at the Broadway Arts studio. It’s a little space. By the way, the Broadway Arts Studio is the one that’s replicated in All That Jazz.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hWURas7fYwk

My late wife had seen Cabaret and I hadn’t got to see it yet. I wasn’t really a fan of movie musicals. So I met Fosse. He’s in the middle of the room, and all these dancers are hurling themselves around us. We’re talking in the middle of the room. I’m not a musician but I was a music editor. We talked for a while and I got no sense of whether I was going to get hired or not, but I loved the energy in that room. I just loved the dancers. They would come sliding right up to our feet, and the room was filled with heat and sweat – running around, motion, and color.

After that I went over to the Ziegfeld – saw Cabaret – and I came home that night and I told my wife, “I want him to hire me. I really want to work with this guy.” And it worked out. That led to Lenny and Lenny led to All That Jazz and that led to some other stuff, then Star 80 and then he died.

HULLFISH: I remember seeing Star 80 when I was fairly young and found it very disturbing.

It’s this Svengali-like figure with a lot of women and a lot of degeneracy.

He was in show business all of his life and the guy – the husband of Dorothy Stratten – he was a hanger on. He was kind of a guy looking to make his career on her. Fosse had a lot of contempt for show business He also loved it. Which I think is a line from All that Jazz. “I love show business, I hate show business.” That’s all he knew… that’s not true. He was a very bright guy. Very well versed in psychiatry and many things and he hung with good people: Paddy Chayefsky and Herb Gardner and a whole bunch of New York people.

That’s really how I ended up doing Network. I’m pretty sure Bob suggested me to Paddy even though I had done two films with Sidney, it’d been several years in between.

© 1985 Universal Pictures

To get back to the question about screening: after a day of shooting, having the crew go into a theater and watch the dailies… you learned a lot just from sitting there. Directors never said much to me, but you learn something just from being in the room. You’re sometimes there till midnight. In Chicago sometimes with John Hughes, later than that. He’d shoot all day and into the evening. One night my crew and I got a late call that said “John’s not going to be in until midnight.” So we went to the movies.

HULLFISH: So you started screening dailies at midnight?

HEIM: Somebody told me that they did a TV show where they’d shoot all day and then the director would come in and work with the editor on the previous day’s material. So that puts you into midnight or early morning. It’s crazy. It’s a young man’s game.

HULLFISH: When did you switch from editing on a Moviola or a KEM to Avid?

HULLFISH: A lot of people liked to screen on a KEM, right?

HEIM: I never did. We did Lenny on a Moviola and Fosse was having trouble seeing the screen, so we did All That Jazz on the KEM. So I would adapt. I preferred the Moviola, I was faster on it. I didn’t have to stretch over those tables.

HULLFISH: So you moved to Avid in 95 because…

HULLFISH: Thelma is still on LightWorks. Why do you call yourself a storyteller? How does the editor actually tell a story in the edit room?

HEIM: Working in film, you manipulate time. The editing process is really the last opportunity to change the story before it goes out into the world.

How do we tell a story? It has to do with the rhythm – of the pace of it – you can turn a picture into something completely different, in the editing process, than was intended. You can’t really get away from the script, nor would you want to, but there is a lot of excess material in the script as there always is. So we just try to make the story better. We try to make it more concise. We try and direct the audience to what they should be looking at any given time.

Stanley Kauffmann who was a film critic of some repute in New York said, and I paraphrase here, “You always want to watch the person you’re watching. Even if you didn’t know it at the time.” Now that’s what an editor does. Where you put a reaction shot… where you stay on somebody and you don’t cut… you’re trying to lead an audience.

The other thing you can do: Beatrice Straight played William Holden’s wife and there’s a scene where she confronts him: How long has the affair been going on and it’s in the kitchen and the kids walk in. It’s two and a half minutes long and Sidney and Paddy Chayefsky and Howard Gottfried – who was Paddy’s partner – and the co-producer said we got to lose it. I said, “No. I don’t think so. It’s a really great scene.” They said, “It is slowing down the picture.” I really argued for keeping the scene. Also, I thought we should tale that scene and put it before William goes off to the beach to that horrible scene where they make love and she just talks about television the whole time. That horrible wonderful scene. In the original script, they were in the opposite order. I said we have to turn those two scenes around and they were adamant not to do it.

Finally, our producer, Dan Melnick, was flying to New York, so I said, “Let’s let Danny decide.” So Melnick sees it – he sees the whole picture. Monday morning I got a call from Howard Gottfried and he said “Aaaa-lllllan…” – he kind of sung my name, and you know when people sing your name something weird is going to happen. He said that Danny came up with this great idea to keep the scene and switch the two scenes around.

So I said, “You know Howard – I don’t usually say this or anything like this – but that was my idea and you were fighting it for two weeks.” And he said, “Does it matter where a good idea comes from?” And you know he’s right. It was a very valuable lesson. And the scene stayed and she won the Academy Award for that two and a half minutes.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kZIAEtw9X_g

HULLFISH: It was a great performance, but why specifically did you argue for the scene as a storyteller?

HEIM: I loved everything in it, but I also thought it was very necessary. Here’s a guy who devoted his whole life to this television network and his wife clearly played second fiddle to his career, and now it was turned around a little bit.

HULLFISH: And why switch the order of the scenes?

I knew Paddy Chayefsky is a hell of a writer. Spectacular. So when Paddy is saying that I had to really fight for it. I don’t usually fight for a scene. Usually I do it much more subtly over the course of the edit, if I really feel strongly about it.

HULLFISH: It’s about trusting the process, right? Yes, you can try to force it, but it’s better to just see what happens as context changes and as needs change and maybe the director becomes less attached to the emotion of the shoot.

HEIM: Right. Been there a couple of times.

HULLFISH: That’ a balance, right? You have to have enough ego to know that you have something to say and you’re strong in your opinions, but set enough of your ego aside to be in service to the director. You have to be willing to address notes.

HEIM

I took notes from everybody. I mean anybody who had a good idea or what I thought was a good idea or a worthwhile idea, I would take a shot at it. I always tell editors it’s not your movie, it’s the director or the producer or somebody else who owns that movie. You can contribute, this is where the editor comes in. You edit it. You try and correct mistakes. Keep the story and the path it should be on. It’s not your movie.

They always say you should do invisible editing, which is bullshit, but it depends. You have to listen to the material. You have to feel the material. I used to think that when I worked with film it was almost like a plastic medium… like if you bend a piece of steel a certain number of times, you’ll eventually break it.

It took me a while to feel that with electronic editing, but I don’t think I’ve ever changed what I do, the style. I’ve watched some of my older movies recently and I don’t think I would make many changes in them. I might speed up a couple of scenes. When I cut scenes now, I tend to make them a little bit faster.

HULLFISH: I was just talking to someone about storytelling, and about how a joke is a good way to practice storytelling. It’s really just a short story. You don’t want to ruin it with too much detail or making it too long. Set it up and get to the point.

HEIM: Yes, but there are there are other details too that you need.

Mel Brooks would explain it’s not enough to say, “It’s a car.” You have to say, “A Buick with three holes in the fender.” A little detail doesn’t hurt. And it depends on where you put the detail. It’s all in the timing. It really is rhythm and delivery. A friend of mine wrote a book called “The Lean Forward Moment.” Interesting idea that you lead the audience in a certain direction and then you pull the rug out from under them. You push them into the next scene.

I hate exposition. Most editors do. And I worked in films where I’ve told the audience something three times – verbally told the audience something three times. They don’t get it. So you cut one out. Now it’s two times and they still don’t get it and you’re cut down to one and that’s enough. They get the second and third time. You’re boring them. They know it, sometimes you don’t even need the first time. For me that would be the ideal filmmaking: information without telling anybody. Just let them discover it. If you can make the audience complicit or make the audience feel something, it’s hard. There’s a lot of visual stuff like Jaws. A shark jumps out from behind the pillar and you don’t expect it. It makes you jump, that’s easy. But to do it in a dialogue scene, and have people follow every word and feel it. That’s that’s hard. That’s rare. I was delighted the first time it happened: when the audience applauds at the end of the opening number of All That Jazz. Because you don’t see audiences applaud, or in the Notebook when people are crying.

HEIM: John Hughes had that ability to do meaningful and funny. He could reach the audience. His stuff reached on a very elemental level. He was really a good writer.

HULLFISH: Earlier in our discussion you mentioned that we rarely get to cut scenes in sequential order. Almost never. Talk a little bit about that or about scenes where it sounded looked great when you cut it originally, but then, in the context of the film, it changed in some way.

HEIM: When you look at dailies, you’ve got to start somewhere. I look at them and they say, “Well, I want this scene to start on the closeup of the actor.” So I edit the scene based on that choice. And then when you put that scene in context of another scene, maybe you can’t go from the previous scene to the close up of the actor for whatever reason. So then you have to start shifting. Or sometimes you’ll have a scene that says exactly the same thing in a different way than a scene that’s elsewhere in the movie. So you you start shifting.

You can’t be rigid. Once you cut the scene, it’s really nice, it’s really good. But then you look at it in context and you say, “I don’t need this or maybe I only need half of it.”

These are the decisions you make with the director. But when I do a first cut, I put pretty much everything into it that was shot because I think that everybody deserves to see that. You can’t take it away early.

And when you’re trimming a first assembly down from its initial length, sometimes it’s easy to get the first half hour, but when you have to start cutting an hour or an hour and a half, you begin to feel holes. And I’ve never liked gaps in a story.

HULLFISH: One of the things that I learned from writing this book was that I needed to let my director see all of the lines in every scene, even if I was very confident that the lines would eventually be cut. It seems like common sense, but I felt like, “If I’m right, then why show them?”

HEIM: The problem is a director has a rhythm. The director knows what he shot. Sometimes they’re wrong. Sometimes they’ll say, “Where’s the shot of the finger? There was no shot there.” Most of the time there is. Sometimes you find something after a slate or something.

Fo you, the director knows he shot those lines you took out. So you’re starting off really badly because you’re throwing the director’s rhythm. Later, you can ask, “Do we really need those three lines?”

HULLFISH: I wish I had learned that earlier: the director needs to the scene. I got to see it with and without. The director never got to see it, so he can’t come to the same conclusion, so he never owns the decision. Lesson learned.

HEIM: I don’t know how editors learn that stuff nowadays. Now it’s learning on the job for most people.

HULLFISH: Alan, thank you for a great discussion. It was a pleasure to speak with you.

HEIM: My pleasure as well.

This interview was transcribed with SpeedScriber, which has recently come out of public beta and is now available.

The first 50 Art of the Cut interviews have been curated into a book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV editors.” The book is not merely a collection of interviews but was edited into topics that read like a massive, virtual roundtable discussion of some of the most important topics to editors everywhere: storytelling, pacing, rhythm, collaboration with directors, approach to a scene and more. CinemaEditor magazine said of the book, “Hullfish has interviewed over 50 editors around the country and asked questions that only an editor would know to ask. Their answers are the basis of this book and it’s not just a collection of interviews…. It is to his credit that Hullfish has created an editing manual similar to the camera manual that ASC has published for many years and can be found in almost any back pocket of members of the camera crew. It is an essential tool on the set. Art of the Cut may indeed be the essential tool for the cutting room. Here is a reference where you can immediately see how our contemporaries deal with the complexities of editing a film. In a very organized manner, he guides the reader through approaching the scene, pacing, and rhythm, structure, storytelling, performance, sound design, and music….Hullfish’s book is an awesome piece of text editing itself. The results make me recommend it to all. I am placing this book on my shelf of editing books and I urge others to do the same. –Jack Tucker, ACE