HULLFISH You’ve been a long-time collaborator with James Cameron.

BUFF: I remember the first time running a scene for Jim. It was on film, of course, in those days. I was very nervous. I had never worked with him before. And I ran the sequence, it was the sub chase, (on “The Abyss”) and afterwards, he sat back and said, “Well, that doesn’t suck!” (Laugh) And from that point on, we’ve gotten along wonderfully. He’s given me complete freedom to sink or swim. He generates an enormous amount of material, but he generates an enormous amount of good material, so that makes it all the more subjective in terms of structure. And for some reason, he’s just always felt comfortable with my choices. Most of my work wouldn’t get changed very much, if at all. I do respect the guy a lot. He certainly does his homework and works harder than anyone on the film. He loves all of the different areas of filmmaking. . He’s very prepared. But at the same time, there’s a lot of freedom working with his material. And he certainly has let me explore it, with happy results. The funny thing is, on several of the films, the producers have said, “Jim won’t need you or anyone this time because he is going to edit the film, himself.” And it never proves to be the case, because he’s too consumed with all the other details. Ultimately he ends up inviting me, or in the case of “Titanic,” Richard Harris back, as well, to take on different sequences to help get it done. But he’s not sitting over our shoulders. It’s lovely.

HULLFISH Do you find that a lot of that collaboration is simply showing him the work that you’re doing, or is it a lot of talking? How is the collaboration actually happening?

BUFF: I think it’s just a matter of interpreting his material. The second film I worked with him on, “Terminator 2,” we actually would do marathon daily sessions on Saturdays. We’d go five and six hours at a time because Jim wanted to look at all of the material with us. The next two films, fortunately, we didn’t endure that kind of pain of six hour marathon sessions every week. I think he just finally got so comfortable with whatever we were doing to interpret his material, he let go and didn’t give us notes. So, on the last one I did, “Titanic,” we hardly ever spoke. He was in Mexico, shooting, when I started. I just worked at his house in Malibu. We had editing rooms set up there. And just took the material and did what I normally do which is react to things I like and try to communicate the story. And then, he would look at sequences and say, “Great!” Or if he had a question, or wanted to explore something himself, he could always grab it and rework it. But honestly, I watched that film a couple of years ago, when it came out in 3D, and I just remembered that so much of it was seriously untouched, the sections that I did. I felt good about that.

HULLFISH Describe how you watch dailies. Do you take notes, do you put locators in, do you watch everything, do you watch them back to front? How do you actually look at dailies?

BUFF: I think that if you don’t watch everything, you’re not doing your job! (Laugh) Things have changed, certainly. The days of screening dailies in the evening with the director, after shooting, are pretty much vanishing or have vanished.

HULLFISH You’ve gotta watch everything. But how are you watching everything? Are you going in order? Are you watching in the order it was shot?

BUFF: I like to watch in order, because you can see how things develop. You can read between the lines. You can glean information. You can see how things transpire. And sometimes you occasionally get notes, in a sort of third-hand way, watching how a scene develops and see what a director may or may not be going for. But for me, it’s always looking for performance. What do I like and what I react to? In the old days on film, it would certainly be presented in order. I would sit there with a notepad, with or without a director, and make my own notes about “Oh, God, I love that reading.” “I love that look.” or “I love that composition, photographically.” Whatever it is that inspires you. And then, I try to go back and harness all of those things that I liked. Sometimes, you run into problems trying to make the scene work and incorporate the bits you love. But usually there’s a way. I don’t find it that much different now except the random access is quite lovely, but I’m still starting at the top and doing a sort of linear review to watch the progression, to see how the actors change, look for subtle differences. Again, it’s very subjective and kind of seat-of-the pants; an emotional response to the material. What do I like? I remember when I was starting out, always worrying about, “God, what is the director going to like?” And finally, when I released myself from that bondage, of trying to anticipate what somebody would like, and going off, what do I like, that was quite freeing. It allowed me to just go down roads that I wanted to go without second-guessing someone. And it just made things stronger in every way.

HULLFISH Many of the other editors I’ve talked to have said that you cannot think about what somebody else is gonna like. You gotta go with your own intuition or else you’re going down a bad path!

BUFF: (Laugh) Yeah, exactly, exactly!

HULLFISH So, you’ve watched the dailies, then what’s your approach to a basic scene? How do you get into it? Do you feel like you’re gonna start from the beginning or do you find this beautiful nugget in the middle that you need to work to?

BUFF: Well, I’ve had occasions, rarely, where I might start in the middle, or I might make a connection between two things that are not at the beginning. I remember on “True Lies,” in fact, watching hours and hours of a sequence at the end of the film where Arnold flies up and tries to rescue his daughter from the bad guy. And there were different techniques that Jim employed, one of which was this Harrier jet that’s suspended on a crane that was spinning, but also the cameras were revolving around. So, there was a very, sort of, rare, serendipitous moment of this little piece that I responded to which really was in the middle of the sequence. But… you had to wade through every hour of material to find something. I remember there was this one piece that was just particularly unique. And I started building the scene from that middle section, outwards. But normally, I would start at the beginning. And I find that once I start at the beginning, and figure out where I’m going to start, I try and anticipate what I’m coming from – the scene that I am coming from may not have been shot – but I’ll certainly consider the likely design of what’s that going to be and where I should begin with this scene. Once I start, it just sort of becomes automatic, how I roll down the road, essentially….

HULLFISH It just flows through, right?

BUFF: Yeah, it just flows, it just flows. And then, I try to harness the pieces that I love.

HULLFISH That makes sense. You were talking about dailies, that you like the non-linearity of how it works, now. Are you using locators instead of the paper notes you used to take? Are you still doing paper notes?

BUFF: I don’t really use locators… with rare exceptions. My preference is to just really remember pieces. One thing I do, when I’m finished with the scene, at some point, I will go back through and scan through all the dailies again, just to see if there’s some nuance that will help enhance the scene and reinforce it, make it stronger, more interesting. So, I’m very thorough with examining the stuff.

HULLFISH You might not know what the scene before or after it is going to be because it hasn’t been shot, so do you find that when you finally get an assembly edit strung together that the pacing or something within the scenes that seemed perfect when it was a single scene, now, in context, those things change? Do you have any examples of that?

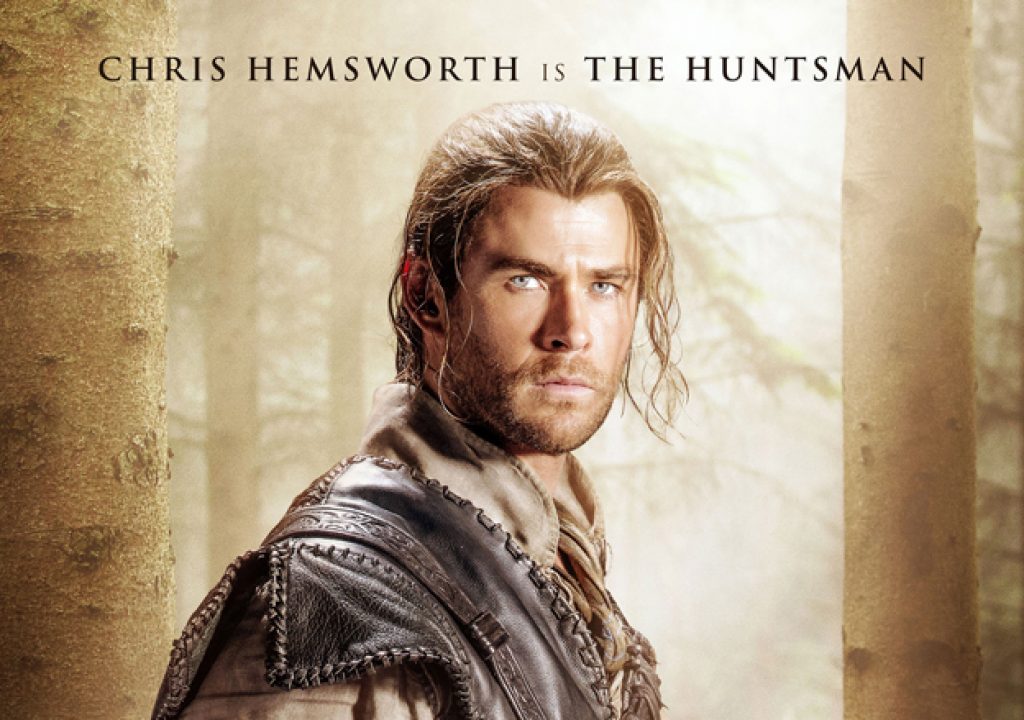

BUFF: I think every film has that problem for the most part. You find out that the scene is a just a little indulgent – a little fat in context to where it’s living within the film. By the time you get to that scene, perhaps the pace needs to be affected, so compression in some form needs to take place. Or perhaps: “Do we need the scene?” Or is there another way or another area that it can live in? Or can it be compressed in an interesting way? In “The Huntsman,” the first act, there was quite a bit of development with these two young kids who ultimately become The Huntsman (Chris Hemsworth) and Sara (Jessica Chastain), but a lot of it went on too long. So we had to find interesting ways to compress it. It seems to be a normal process but, initially, I’m going to try and include everything. I don’t want to throw anything out until we can kind of see it more in context. I may have instincts that I want to get rid of this or compress something – but for the director’s benefit, and to get them up to speed, and in sync, and see what his or her reaction would be, I want to preserve everything that they shot, as closely as possible, and then, collectively – together – we can prune it accordingly. Everything I read these days is too long (laugh). And frequently, Act One is too long and you wish and hope that before they start shooting a writer is able to compress it on the page as opposed to us, having to do it, editorially. But so often, it’s us.

HULLFISH (laughs) Yeah. So, I take it that when you say that everything you read is too long, you’re talking specifically about scripts and not just the last novel you read on your bookshelf, back there (laugh)! Do you have a chance to speak into anything you are editing?

HULLFISH Let’s talk about some of the discussions that occurred when you’ve finally strung out the entire movie for the first time and you start realizing what is fat, what’s a little long. Where the pacing over the whole movie is too slow or something. What are some of the decisions that are happening? Why did we cut this scene? Why did we chop this scene in half? How did some of those decisions happen? Can you remember any of the scenes that were deleted from “Huntsman” and why that choice was made?

BUFF: Off hand, I don’t remember and I know there were some and there were some experiments where we deleted scenes and then, restored them based on screening groups….

HULLFISH Why did they get restored?

BUFF: Well, there’s a scene at the beginning of “The Huntsman,” where the Charlize Theron character poisons a king, which is part of this prequel in that film. It was shot at night, interior, fire lit, castle scene, followed by another interior, night, fire lit, castle scene between Emily Blunt and Charlize. There’s something a little claustrophobic about the beginning. There’s probably four minutes of sitting in this dialogue-driven, non-active interior that kind of suggested maybe there’s a way,…maybe we don’t need the Charlize scene. We’ve seen her murder kings in the past. But then, we tried taking it out. Producer agreed with it; he liked the idea of not having it. But [the] Director was missing it and argued for restoration because not everyone had seen the previous film. This being a sequel, he felt we need to know right away that she’s the villain.

HULLFISH She’s capable of anything.

BUFF: Yeah. And probably he didn’t want to have to tell her that the scene was cut out of the movie either (laugh)! So we played with that two different ways, one without…. Then, unfortunately, the whole beginning, the studio decided that we needed a lot of narration to solve their issues with the prequel/ sequel movie. Very problematic. So, a whole different opening was designed and re-engineered. It’s quite a process sometimes, when there are a lot of hands in the pie, and opinions, and the director doesn’t have final cut. That’s, of course, the wonderful thing about working with Jim! He has final cut (laugh). And there’s one voice, you know, which is terrific….

HULLFISH You were talking about getting notes from everywhere, but obviously, some notes are good things. So many people think test audiences are the bane of good film. But a lot of times they reveal interesting things.

BUFF: Yeah, they do.

HULLFISH Talk to me about sitting in on a test screening and the things that you realize as you watch with an audience.

BUFF: I think it’s important to run it for people, particularly if you can get objective people, that are not friends or studio people. There are a lot of friends-and-family screenings that are utilized for this process at the studio level. But I think it’s better to have a more objective, real-world audience when possible. There are always things you learn, and great surprises, good and bad. You find out where laughs start, appropriate or inappropriate. One film I worked on, quite a few years back with Jim Sheridan, was called “Get Rich, Or Die Trying.” It was an autobiographical film of Fifty Cent, the rapper, and there were quite a few emotional scenes in it. One, towards the very end of the movie has Viola Davis playing his mother. In the scene there was mucus coming out of her nose. Somebody in the audience yelled something at the screen that was silly and inappropriate that just was catalytic and screwed up the whole screening. Because of that, some silly remark from some teenager, but that indicated, “Well, we have to clean that up (laugh)!”

HULLFISH When you watch a film with an audience, you don’t need to hear what they say on their little note cards, right? You just feel it.

BUFF: Yeah, pretty much, you feel it, yes, indeed. I’ve had screenings though where it’s very hard to read the audience. You certainly find out where there are pacing issues or clarity problems. Maybe we need to slow down and reinforce this piece of information. I don’t want to do five of them, but I’d certainly like to do at least one.

HULLFISH Talk to me a little bit about your early career. You came up, it looks kinda through Visual effects. Did you always want to be an editor, and just came up through Visual Effects, or did you want to be in Visual Effects and you ended up in editing?

BUFF: No, I was interested in editing. And Visual Effects was a means to an end. I had worked in commercials as an assistant editor, and became an editor for about five years, and felt I had learned pretty much everything I could. It’s a great training ground, technically to understand, back in those days, opticals. Juggling 10 different commercials simultaneously, in various stages of finish, from editing the first one, to mixing another, revisions on another, dealing with opticals, titles, clients. But I tired of it. And a friend called me up one day and asked “Do you know anybody who’s in the union, any assistant editors who are any good, who understand opticals and are available?” And I just said, “Me!” I didn’t even know what I was volunteering for! Well, fortunately, it turned out to be working on a television series called “Battlestar Gallactica.” And John Dykstra’s company, ILM, was in the San Fernando Valley at that point and they had just finished the first “Star Wars.” They needed somebody. I don’t think they even called it editorial; something like, “Film Control” or some awful name. They needed somebody who understood editorial and the optical process. I was there briefly and ran into an old friend that I hadn’t seen in years, Dennis Murin , who was the Visual Effects Supervisor. I met Richard Edlund as well. They were branching off to setup ILM for the second Star Wars film, “Empire Strikes Back” and they were moving to Northern California. But some of the folks, Dykstra and Company, were staying in Los Angeles. There was some split. They asked me if I wanted to move north and I thought, this is a certainly nice (laugh) opportunity. I always wanted to get paid to work in film, especially on that film, and help establish ILM. It was great! So, I stayed there for five years and worked in Visual Effects. The last year I was there, I managed to work as an Assistant Editor rather than Visual Effects. They said, “Oh, that’s a step down, isn’t it?” I thought, “No, not at all (laugh)!” I went from running the Visual Effects editorial department to assistant editing on “Jedi.” And then, my wife was offered a job in Los Angeles to help set up Boss Films which was doing the Visual Effects for “Ghost Busters” and “2010.” Then I got an opportunity to work as an assistant editor on “Jagged Edge,” a film that Richard Marquand was directing and he had directed “Return of the Jedi.” His editor asked me, if I would like to assist him, which I did. And that was sort of how I made the transition to Live Action.

HULLFISH What was the jump from assisting to editing?

BUFF: Well, that was very strange because I ended up with a credit as an editor on “Jagged Edge” and that was a technicality because I had accumulated enough years with the union, at that time that I had an editor’s card. On the film, it was required to have a stand-by editor, because Richard Marquand’s editor was British. So, the head of Post Production at Columbia discovered that I had that card and said, “Well, we’re going to have to put you up there, as well.” So, I shared a credit with my friend, Sean Barton, who cut 99% of the movie, and I did a scene or two (laugh) and got a credit. But then, based on that, I got a wonderful film called “Solar Babies,” which was my first solo effort. Mel Brooks was producing that. It was shot in Spain. All of the post production was done in Los Angeles. Based on that experience, Mel asked me to do “Space Balls.” I said, “I don’t know anything about comedy, Mr. Brooks.” He said, “Don’t worry about the comedy, kid. I’ll take care of that! (laugh)”

HULLFISH (laugh) When did you switch from film editing to non-linear editing, digital?

BUFF: Over the whole course of my early career, there were various attempts at electronic editing that came along. The CMX, the Editdroid,….

HULLFISH …Montage,….Lightworks,….

BUFF: Sure, Lightworks, Montage, yeah, but even before Lightworks, Montage, all of those things. And then, finally Avid came along, but it was only in the commercial world. I had friends that used it, and I thought, “You know, I’ve been waiting for years. I figured something was going to take over and I was always worried that somehow that electronic world, that I would be – in terms of union – I thought, it might be a separate union that took over that world and that I would be excluded somehow from the opportunity to utilize that kind of technology. But I figured that day would come. But there were never any systems that I liked that worked, except Avid. I took a class in Avid, for about a week, at USC, just on my own, for my own edification, never having thought I would apply it to anything. Lo and behold, Roger Donaldson was doing a film, “The Getaway,” a remake of “The Getaway. “ The studio said, “Hey, we have a compressed post schedule, we would like you to use the Montage.” I said, “No, way! We’ll either get two editors and we’ll do it on film, or let me try the Avid.” At that point, this was about ’92, ’93, something like that,…

HULLFISH That’s exactly when I started on Avid.

BUFF: There you go! The director loved the idea. The studio was very hesitant. And I said, “Look, it’ll work! It’ll work! It’ll work!” We were using optical drives. I couldn’t even play the whole car chase back for Roger (laugh). I could play half of it, but he was wonderfully accommodating, and embraced the technology. Anyway, it worked. I found an assistant, Joel Negron, who is now a full-fledged editor, because he had some electronic and digital experience. Between my normal assistant, who was very film savvy, and Joel and myself, and Roger’s sympathetic attitude, we did “The Getaway” all on Avid. I thought, “Well, that will be the last time that I ever use it.” But then, Jim Cameron called and said, “I’m gonna do this movie, ‘True Lies.’” And I said, “Well, I gotta turn you on to Avid.” He was very hesitant, and then, embraced it. Once that went off, it just kept going and we never did film, again.

HULLFISH ’92, the first Avid system that I started working on was purchased for “The Fugitive” which was shot here in Chicago.

BUFF: Those days it was a little scary.

HULLFISH Yeah, not much to look at.

BUFF: For a big scale movie, how do you manage all of that media? By the time they got to “True Lies,” we had those shoeboxes,…. I forgot how many,… how much storage they had that you could play. You couldn’t play an entire reel at that time, as I recall.

HULLFISH They were 5 Gigs, or some crazy number! 8, I think 8Gigs and you bought 5 of them to get 40Gigs! Now, you’ve got a thumb drive that has quadruple that. So many of the films you’ve worked on are effects heavy.

BUFF: Particularly of late, yeah. I get typecast (laugh). My personal preferences are the ones that were not that way (laughs)! “Training Day” I liked, “13 Days,” “Antoine Fisher,” more dramatic things, or thrillers.

HULLFISH With VFX stuff you’re trying to edit, but you have to do a lot of imagining:

BUFF: I think based on your experience, you know how long a shot is supposed to be on, even what’s going to happen in the action. And if you are lucky enough to have a storyboard, we’ll plug that in as a placeholder. Or any kind of imagery that will help convey timing. There was this fight sequence in “The Huntsman” with this creature with some pre-viz. What I was just going off were purely just instincts of a shot: a plate with no character and imagining him picking up a stick, stone whatever and how long does that stay on the screen. Ultimately you start to get either pencil tests or pre-viz. It’s a lot of imagination editorially speaking just for timing. How to convey that to a producer is impossible and studios can’t look at anything essentially unless it’s incredibly well finished

HULLFISH Do you blame that on Avid? The fact that studios have to see something that is incredibly finished on nonlinear editing? Back in the film days you couldn’t have delivered something incredibly finished to the studios.

BUFF: The expectation is quite different these days then it used to be. You know things have to be all tracked and perfect as possible for them to appreciate what it will be. There seems to be a lack of imagination and an inability to pre-visualize things. It’s just the nature of how things evolved. Digital has contributed to that, they expect pretty polished results pretty quickly.

HULLFISH You’ve done a lot of visual effects stuff but talk to me a little about sound effects and sound design. How much does that inform your editing or how much does that help sell your visual cuts

BUFF: Sound design, particularly, there may be key sound effects that impact timing so the placement of those, the character of those are important to me. Sometimes background, just a simple background, is important to me but not always. I’m always interested in applying effects, in many ways I’m more hesitant applying music because it’s so seductive, it can sell anything and it can also misguide you or misguide the uninitiated to accepting something that isn’t quite right. A lot of young editors will cut a scene to music and I want to cut the scene then cut the music to fit the scene. I think that’s probably true of most editors.

HULLFISH So many people have said exactly the same thing: to put temp score in something is very dangerous…

BUFF: I think it is, early on. Until you have to present something to a studio or an audience. It colors things in a way which can be misleading and makes things look great when in fact there may be more work to be done. I know that if I have any dignitaries visiting the cutting room then I have to make the director look great so I’ll add music to something. There are times where there might be scenes where you might need to apply it just to give the right impression. That the scene dry might be too difficult to understand, but I’m very careful about applying it too early. Ultimately a temp score is developed because we go screening and testing, unless you get mock ups from your composer, sophisticated mock ups early enough that you can incorporate those. I would rather have the composer give me the material that’s coming out of his or her brain. But temp is important at some point for sure

HULLFISH Could you take a look at a few scenes I was able to get from “The Huntsman?” Do you have anything you could tell us about the editing of these? Approach? Difficulties? Why you did things? What you reacted to in the dailies and how you tried to tell the story?

BUFF: This was fun to put together, playing the comedy and reactions from the characters. Meeting the female dwarves always gave me a chuckle.

BUFF: This was one of my favorite scenes but is truncated here. I liked the performances of Emily and Jessica, the deception that’s going on dramatically and the lighting/cinematography, the way it is was blocked and staged by the director…all avery successful. It’s a fairly long scene w/o action, but full of tension and surprise. Very difficult to shoot as the lighting was constantly changing and it was under the Heathrow landing path so performances for both reasons were frequently interrupted which put an emphasis on my ability to balance it all out seamlessly.

BUFF: This was one of the director’s favorites as it pretty much plays as a single take and he got the performances he liked…only about two cuts editorially.

HULLFISH: Great talking to you. Thanks for sharing such great insight about editing.

BUFF: My pleasure.

To read more interviews like this, follow THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish.