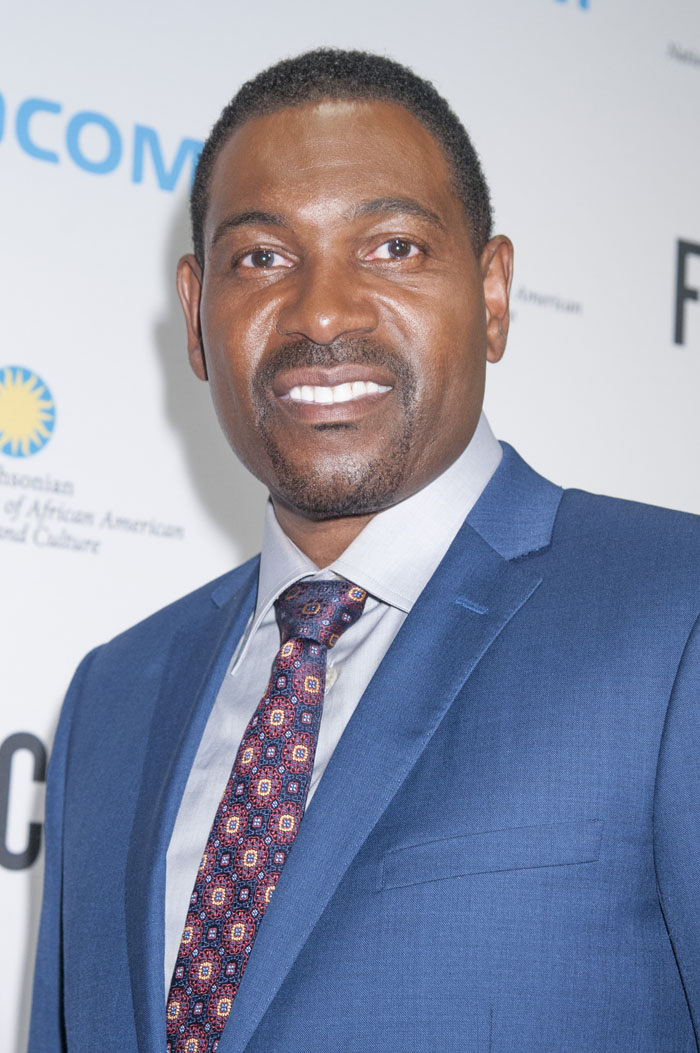

Hughes Winborne, ACE, is an Oscar-winning editor (Crash, 2005) who has cut more than two dozen feature films including Billy Bob Thornton’s Sling Blade, The Pursuit of Happyness, Seven Pounds, and Guardians of the Galaxy. His latest film is Denzel Washington’s adaptation of August Wilson’s Pulitzer Prize-winning play, Fences.

HULLFISH: Hughes, we have something in common. I have just been cutting a film with Mykelti Williamson in it and he’s in Fences, too.

WINBORNE: Mykelti’s great. His performance in Fences is so endearing. He is reprising his role in the play on Broadway. The play is amazing. The film, as far as the dialogue is concerned does not stray from the play as it as presented on Broadway. Like the play, the movie is all about the words, and so the editing has to be fairly precise and discreet. It’s a tricky thing. A lot of people don’t appreciate the challenge of putting together a film so driven by dialogue.

HULLFISH: I agree.

WINBORNE: The first half of Fences is primarily dialogue. The Help was of the same ilk. Two hours and eighteen minutes of talking. Keeping an audience’s interest for that long is challenging. It requires making sure that the dramatic tension sustains so the audience will climb on and stay for the ride.

With Fences it’s a matter of getting the rhythm right because the rhythm is very precise. You get caught up in this rhythm. This may seem weird but it’s a bit like listening to a great song. It doesn’t really matter if you miss some of the lyrics. If you’re getting the rhythm and the tone, you’re probably feeling emotionally what you need to understand the film.

HULLFISH: That seems to be the truth for a lot of adaptations of plays. David Mamet’s Glengarry Glen Ross comes to mind. The language – and the rhythm of the language – is critical.

WINBORNE: Exactly.

HULLFISH: Tell me about landing this job. You did The Help, you did The Pursuit of Happyness, Crash; those all have some element of race relations or at least have heavily African-American casts…

WINBORNE. I did Great Debaters with Denzel and that’s why I’m doing Fences.

Fences has an all black cast yet race is only one element of the film. It is really about many things and it’s up to the audience to decide how the movie works for them. There’s no agenda. It’s the most un-manipulative film that I’ve ever worked on. It was a challenge to stay out of the way. Editorially, it is a prime example of trying to stay invisible. It’s a very universal story told in a way that allows you to plumb what you will. The editing should not and does not tell the audience how to feel. I think, in some ways, people won’t recognize what was done editorially – which is okay because that was the intent.

(Photo: Alex J. Berliner / ABImages)

What are you going to do with a movie that’s based on a Pulitzer prize-winning play? You’re going to stay true to the language and the intent of the play. That was the challenge for everybody: actors, the DP, the composer. The music in this movie is beautiful, but people probably won’t even notice the cues until the very last cue of the movie, which is quite beautiful, but the composer did an extraordinary job. He had to make a score that was almost transparent at times. By the way, in case it’s not obvious, I’m more excited to talk about this movie than anything I’ve ever worked on. I really do believe it’s the best film I’ve ever been a part of. It has been an honor to be associated with this movie. Everybody involved in post felt the same way. You just don’t get to bite into material this strong very often. A movie like this comes along once in a lifetime

HULLFISH: You said that the score is kind of invisible and that was a challenge and that your editing needed to be invisible. Did you find that you tried not to cut, or did you find that you needed to hide your cuts very well? There’s obviously a difference there. Talk to me about that.

WINBORNE: It wasn’t that I tried not to cut. What I tried to do was not to interfere with the rhythm of the language. I had to find the right frame to cut on. And if I didn’t find it, Denzel would, because he knew the rhythm inside out. I had my cut ready a couple of weeks after Denzel came back from shooting in Pittsburg. It was pretty close. It was probably 85% there but the last 15% I did with Denzel was huge. It was almost all about the rhythm. He has such an ear for the sound and rhythm that if I got it wrong he usually knew how many frames I was off. “You’re four frames off with that edit” and I’d change it four frames and bang.

I didn’t try not to cut, but I tried to make sure that my cuts were not trying to make a point. I tried to hold back until it was the right time. That’s easier said than done. As an editor, you sometimes just want to make that first cut.

HULLFISH: You want to manipulate to show that you’re doing your job.

WINBORNE: That’s right. I don’t know about you, but for me there’s a certain amount of anxiety about making the first cut in a scene. Sometimes I will make the first cut sooner than I should because I’m too impatient to wait on getting the rhythm started. On Fences I made myself hold back. I didn’t want my presence felt. Don’t get me wrong, there’re a lot of cuts, but hopefully they are all in the right place. Some may consider this film “theatrical” and they are right. I believe that is not a bad thing. It was the right approach for this film. Sling Blade was the same way, Sling Blade probably had about a quarter of the cuts that Fences has. I think Sling Blade had 337 cuts.

HULLFISH: That is not a lot for a feature film…I think the average is about 1,000 picture cuts in a feature… Mad Max: Fury Road, if I remember had almost 3,000.

WINBORNE: Fences is probably between 1500 and 2000 and only that many because its two hours eighteen minutes long. Also, as you know, sometimes you have to make cuts because there’s a flub or a camera bump. However, you don’t want to be controlled by those things. You want to control pace, rhythm, and performance but you don’t want anybody to know that’s what you’re doing. And that’s tricky.

HULLFISH: Hughes, you won an Oscar for editing Crash. I spoke to Job ter Burg about voting on editing awards – and he said: “I want to see that the editor was in control of the material.”

WINBORNE: Right. That’s a good answer.

HULLFISH: Obviously, revealing that you’re in control of the material to a fellow editor is a different thing than somebody in the general audience seeing that you’re in control of the material.

WINBORNE: Right. If I’m in control of the material, it means you’re not going to see that I am pulling the levers. Hopefully, even my fellow editors won’t see my hand at work. Crash was a horse of a different color. It had multiple story lines with constant crosscutting. People came out of the theater after seeing Crash and that’s one of the things they remember. People will come out of Fences and they’re not going to think about the editing. I hope that they don’t. I hope that they will say “That movie was fucking awesome.” And they’re not going to say, “because it was cut so well.” They’re going to say “’cause it was awesome.” They’re going to think “The performances were incredible” because the performances, every one of them, are next level. You just don’t see films with performances, especially across the board, at this level very often.

HULLFISH: It’s gotten a lot of Oscar buzz – especially the performances.

WINBORNE: Unfortunately a lot of the supporting actors are going to be competing against each other just to get nominated. Mykelti is amazing. Of all the supporting characters in the movie, he’s probably – with the people who worked on the film – their favorite. But they’re all amazing. Viola and Denzel are other-worldly.

HULLFISH: I want to talk about two things specifically: One is that you said Denzel was really on top of the rhythms of the film. Was it specifically visual rhythms or was it more the rhythms of the speech and the audio? And talk to me a little bit about your collaboration with him.

WINBORNE: Well, it’s a bit of both of, but it really is the language that was driving the film. It’s not just a dramatic rhythm but the rhythm of the language. If you sit down with this screenplay or if you go look at the screenplay, and read one of Troy’s big speeches and then try to speak it, you’ll see how difficult it is. It’s very difficult language to get out in a long monologue, which Denzel has to do over and over again. But, if you’ve got the rhythm of it, it flows like Shakespeare.

When I was studying Shakespeare in college, I would read one of his plays and not know what the hell was going on. So I would go to the library and I’d listen to it on a record. When I listened to it, it all made sense because the rhythm of the speech was right.

The same is true with Fences. The way it’s being said by the actors is so right that you understand it almost without even understanding the words. So if I interrupt that rhythm with a cut in the wrong place, it throws all the rhythm out.

HULLFISH: Absolutely. My reference for this would be Glengarry Glen Ross, but any David Mamet stuff, the rhythm of that language is…

WINBORNE: Yes. Mamet. Exactly. He just lays it at you. It’s like a machine gun. You’re right. That’s exactly what it’s like. You can’t stop so people can have a laugh or have a cry or have a big reaction because if you do, you lose the rhythm. It’s not a song anymore.

Whenever we had departmental meetings, Denzel would emphasize:

1) the movie is about love, and

2) the language is the music.

So, the cutting can’t get in the way of the language. Every department was given this edict; serve the language and the rhythm of the language. The language is the music of the film. I don’t think there’s any score until we’re 35 minutes in…

HULLFISH: Wow.

WINBORNE: In fact, I think the first cue starts at the end of Mykelti’s first scene. All the cues until the end of the film very, very transparent and placed so as not be ahead of the audience. This was a big thing for Denzel. “The music can’t lead. The music follows.” The movie is so organic that you grow with the movie. The movie doesn’t tell you how to grow. You get there on your own. It’s pretty powerful. It’s intense, but it’s uplifting at the same time. The movie is like life. There’s a lot of sadness but there’s also a lot of love and the ending is really very uplifting.

HULLFISH: What were some of the struggles with temp music when the rhythm was so critical to the dialogue?

WINBORNE: Well, I actually did use some temp. I don’t do it a lot, but because there were certain sections of the film where I needed to have transitions – time transitions for the most part – and sometimes, emotional transitions as well, I did find temp music and I even temped a few times in the middle of scenes.

HULLFISH: Do you remember anything you temped with?

WINBORNE: I used a fair amount from Tree of Life and I used a bit of Thomas Newman. Some from The Help, and there was one cue that came from the most unlikely of places, Spectre.

HULLFISH: That’s interesting.

WINBORNE: They weren’t all the right cues either by the way. When Denzel heard temp cuts he almost immediately said, “Turn the music off.” But it did help me learn where the music was going to work, where it should come in.

HULLFISH: Most people don’t cut with temp originally because then the music affects the pacing of the rhythm of the visual cuts.

WINBORNE: Sometimes you believe you’ve got something that you don’t because the music is giving it to you. I don’t like to use temp music for just the reason you’re describing.

HULLFISH: I just temped with something that had a lot of Pursuit of Happyness in it – which is a movie you edited.

WINBORNE: Oh really? That’s a good score.

HULLFISH: Yeah, it sure is. I used at least six or seven cues, because the movie was about another parent/young child relationship and I thought, you know, what other movies do I know with a parent and a child? So I used some of Pursuit of Happyness and I used some Infinitely Polar Bear and some Little Miss Sunshine.

WINBORNE: That’s a good score, I like that score.

HULLFISH: Have you had any mentors?

WINBORNE: My history as an editor is a little different than most editors. I was an assistant on only one and a half movies and then I was an editor. So I never had an editorial mentor so to speak. I had a couple of directors who helped me along. I learned something from almost every director I have worked with. I typically learned how little I know every time I work on a movie. I worked with Dan Petrie, Sr. on a couple of films when I first got to LA; movies-of-the-week for the most part. What I learned from him was not, for the most part, about cutting. It really had more to do with how to behave in the editing room in order to make collaborating productive: how to interact in the editing room.

HULLFISH: There’s an important topic….

WINBORNE: If you’re an editor, you better be very sure of yourself if you tell a director, “That can’t be done,” which is exactly how I got my first job. The editor on the show told the director that one too many times and after a while the director just said, “You know what? This guy’s not going to try anything I want to try.” So I got bumped up to editor.

It’s more about trying to create an environment where there’s a free exchange of ideas. I’ve worked on films that run the spectrum in that area – somewhere you had to fight just to get a word in and others where it was just a free flowing conversation the entire time. I prefer the latter: where everybody feels like they can talk and you figure it out together. Sometimes that’s not necessary because the film just comes together. The Help was like that and so was Pursuit of Happyness for that matter; they both just came together.

I don’t understand every single scene from the get-go, I need to talk to understand it. I need to have my own process in order to contribute. A lot of times you’re still trying to understand it when you’re only a couple of weeks away from locking the picture. But it’s when you get into those last few weeks that you hopefully are going to contribute the most to making the film work or at least being the best as it can be.

HULLFISH: I’m fascinated with this: the etiquette of the edit suite and the politics of it and the fact that really so much of our job is that collaboration and the interaction with the director. You’re an Oscar winner, and that doesn’t matter if nobody wants to work with you. If you’re miserable in the edit suite and the director has to spend six months together, he’s not going to want to work with you.

WINBORNE: That’s right. That’s exactly right. And you know when I’m asked by directors for recommendations for editors I always say exactly that: “I can recommend people that can do the job, but try to find somebody that you can talk to because you’re going to be spending six, seven, eight months, nine months a year with that person.”

HULLFISH: On Fences, you were talking about the language and the rhythm of the language which I totally get. Talk to me about how you tried to integrate that with the performances themselves or were the performances so universally good that you didn’t have to worry about “oh here’s this great moment in take four and I’m going to really try to get that great moment in take four instead of in take two”

WINBORNE: That’s a good question. Sometimes the rhythms were so good in one take that even if the performance in one section was not as strong – and they were always pretty good – but sometimes if the rhythm was there throughout a take we might stay with that take or even stay with that rhythm rather than switch to what might be a stronger moment from another take. The other thing about editing is that some of these nice moments have to be cut out in service to the film. How many times have you taken out really great scenes to make the movie work?

HULLFISH: Many times. Got to kill your babies, right?

WINBORNE: Exactly. I did that on Seven Pound. I took out a whole character and I felt horrible about it because she was so good and it was like a big break for her.

HULLFISH: I’ve killed a whole character before, too. You feel horrible, especially if you know the actor. I interviewed Steven Mirkovich about editing Risen, and he said he had to kill an entire character, too. The main character is supposed to be a badass Roman Centurion who’s out for blood and he’s got this romantic relationship and Steve thought, “if we lose the romantic relationship it just makes him more of a badass and helps move the film along.”

HULLFISH: Hughes, I’ve kept you too long; I really appreciate your time.

WINBORNE: You’re quite welcome. My pleasure.

For more interviews with feature film and TV editors, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish