HULLFISH: Tell me a little bit about your new movie “Toucan Nation?”

HEREDIA: “Toucan Nation,” is the story of a toucan in Costa Rica that was abused and lost half of his beak from an animal abuser who chopped it off. When I heard this story about a year and a half ago I was actually outraged. It was a story that went all around the world. A group of scientist and technicians from Costa Rica and the US designed a prostheses for the bird which was printed with 3D technology. The film follows how the bird gets better. It follows the scientist designing and printing and operating the beak on the toucan and also follows the popular movement in Costa Rica of activists and the legislators and the president himself who are trying to change the law that protects animals in Costa Rica. I’m very excited that we are bringing this story to Animal Planet.

HEREDIA: I am producing, directing and editing.

HULLFISH: Tell me a little bit about how you’re organizing this in post. I am in the middle of editing a documentary right now. What are you doing to the organization of the material that is helping you find what you need to tell a story?

HULLFISH: I’m interested in bin organization, you said one of the first ways you organize a bin is to divide the cards themselves. So in what other ways do you organize the bins? By scene, or story ideas, or by topics, or…?

HULLFISH: With those selects you are building the larger sequence from those selects reels and coming up with a bridge between those sequences? Or just trying to figure which sequence goes into another? Or is everything chronological?

HULLFISH: The doc I’m cutting now, we started in the middle, jumped back a little, jumped back a little more, jumped back a little more, then leapt back to the starting point. We later changed that to a much more streamlined version where we started in the middle (at a crucial moment) then jumped all the way back to the beginning of the story to show the events that led up to that moment, then showed how that moment affected the rest of the story. So there’re all kinds of structures for telling a story. Tell me about the particular structure for “Toucan Nation.” What worked best? And why did you settle on that structure?

HEREDIA: … and when.

HULLFISH: And when. So let’s talk about “when” a little bit. Concerning the stories or sub-stories or arcs that branch out from the central story: what decisions were made in determining the exact moment to branch away from the central story to tell a sub-story?

HEREDIA: I go back to my own experience. I am my own audience. I react to my edit based on when I feel that it’s time to go to another arc. That feeling is defined by some elements that are rational and other elements that are irrational. Rational reasons are related to “Oh, I haven’t seen the bird for a while. It’s time to know what’s going on there.” But there are also irrational and emotional needs, for example, “I am in a low moment and I need to bring this up.” Or I need to make the audience feel something else. When that moment needs to happen is something that I, as a director and editor, feel in my stomach. There are no formulas, you just go and capture a story, bring it to the editing room, organize it and prepare it and react to those scenes based on the story you want to tell and that feeling that you have in your stomach and your heart and your brain will tell you which way you should go.

HULLFISH: That sounds very musical to me. The idea of ebbing and flowing and low moments and trying to go brighter. That’s a very musical sense I think.

HULLFISH: I don’t want to put you in an awkward position, but those decisions are easier to make when you are the director than when someone else is the director and falls in love with a certain moment and you as the editor know, “This is too long on this.” And even though this is a great moment it has to be cut, right?

HEREDIA: Certainly. When you are working as an editor with a director, a lot of the pacing, as in music or anything else that you do is about breathing. So there’s this arc and you’re breathing and you say, “I need to inhale now because I’ve already exhaled.” When you’re doing it by yourself you feel that and you don’t have to negotiate that. When you’re an editor working for a director, you need to have certain synchronicity in that kind of thing because it’s two people breathing, it’s two people thinking, it’s too people applying their brains and talents to one thing, so every time there’s more than one person in this process, there’s also a reality, but also a need… you need to synchronize yourself with someone else.

HEREDIA: When you are an editor working for a director, you are there to use your talent for someone else’s vision. It’s not your vision. It’s putting your talent in use to make that vision happen. So that’s a very clear role as an editor. You might feel very strong about telling the story this way or telling this part of the story and the other person might be wrong about not doing it, but at the end of the day, it’s not your film. It’s the film of this person you’re working for. So you need to feel very comfortable about sharing your talent and putting it in function to someone else’s vision. You are there to give the director your best advice and your best direction, because you are directing the editorial process but you are not directing the film. You are helping the director go through a process that’s going to help him or her make a film.

HULLFISH: I agree with that, and that was beautifully spoken. But how do you negotiate when you have a strong feeling and you think the director should listen to you, but you also know that it’s their movie? Maybe you don’t think that they’re thinking about the audience, or you think they’re being indulgent? How do you go about presenting that to the director?

HEREDIA: It depends on the relationship that you have with the director. A lot of what editors do is psychology. How you communicate and how you handle your relationships depends on the person you are dealing with. That’s the art of being a communicator sitting in the editor’s chair.

HULLFISH: On many of your films or on “Toucan Nation” do you do screenings for test audiences? And what do you discover in those screenings?

HULLFISH: What’s your personal philosophy about editing or producing documentaries? I just interviewed Craig Mellish, who is an editor for Ken Burns, and he told me that the philosophy of Burns’ documentary company is that they are “emotional archaeologists.”

HULLFISH: When you’re editing, for example on “Toucan Nation,” what was it that you felt about the story at the beginning that you felt that you needed to carry through the process of shooting and editing.

HULLFISH: A long time ago when I heard you speak, you talked about editing a documentary and knowing that you were missing some critical element in the editing room and sending the director back out to get it. That’s one of the strengths of a producer or director who has edited: you know the elements or the ingredients that you need in post to tell your story.

HULLFISH: Talk to me about finding these moments. How are you cataloging them? You said you do a selects reels. Are you making them of everything?

HEREDIA: I don’t do the kinds of selects reels that you’re talking about. I cut the scene. You hope that when the director is shooting that every frame has an intention. Why the director focused on that corner of the room and not in the other corner? There is an intention. So you try to understand the intention of the scene and you have communication with the director to capture that information and intent and you try to translate it with the footage that you have into a scene. And you can look at that long scene as if it was a film. That is where you find the moments. The moments reveal themselves and you play with them. By the time you go to the next stage and you are building the film itself, you know where the moments are. You don’t have to go and look for them in the raw footage. They are already playing for you in those scenes.

HEREDIA: No. In a few of the big, big projects that I’ve done, “The Weight of the Nation,” and “Alzheimers” for HBO, or “Sleepless in America” for National Geographic which are very large projects with a lot of very smart people who usually only talk to those within their own fields or to other scientists. Those films are very heavy on content, but also have scenes that are verite or kind of verite.

HULLFISH: From an editing standpoint where do you begin? It sounds like you always start with a scene.

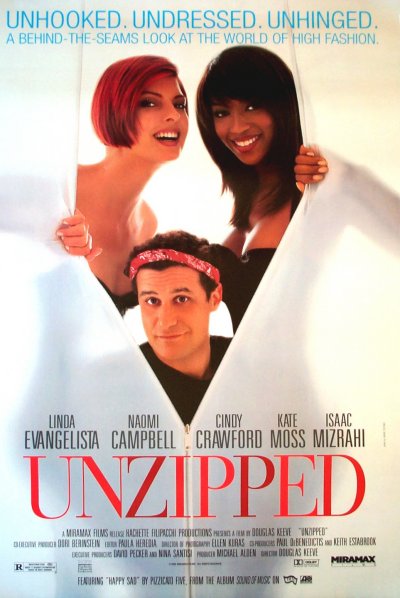

HEREDIA: But you must also remain true to the footage. I remember in “Unzipped” – you remember that film?

HERIDIA: When I had the interview with the director, a few of my colleagues had already interviewed for it and they told me “there’s nothing in there… the footage is all over the place… the camera moves around like crazy… everything is out of focus… what can anybody do with that?” But when I interviewed with the director I understood him and I realized that the craziness of the way that the film was shot was very unintentional, but I could see how that footage could represent the craziness in the brain and the way the director saw life – saw the story itself. The director and the designer, Isaac Mizrahi, were breaking up from a long relationship and all of that was part of that emotional state of the footage. If you look at the footage rationally, it doesn’t make any sense. There’s nothing there. But if you look at the footage and say, “I believe that the director has an intention and I understand that intention then I can take that footage and organize it and bring out of that footage the best that is the vision of what that film is. As an editor you have to start by believing that there is something in the footage and that you can bring it out. That’s a process of cleaning the weeds out of something. And when it’s clean and you play it, you can see it better. When you are doing a documentary with more formal interviews I take those interviews and the director takes those interviews and we mark selects on paper or digital. We begin codifying the selects. Those selects are subclipped and those subclips go into a bin that has columns which will get the codes. So when I am searching for a code, I can sift and bring to my timeline everybody that talks about anything I need. I can immediately see everything that I have in terms of content, besides verite. So when I’m building my next stage of that scene, I can begin weaving both elements.

HEREDIA: For example, in “Toucan Nation” we have an interview of someone and we would codify the soundbites as “popular movement, the law, the beak, technology, philosophy.” Those are kind of general topics, codes, but in a paragraph that’s talking about technology, they might also talk about 3D printing, so I make another code. Eventually you begin merging and simplifying the codification. Usually it starts a little loose and then it gets a little tighter and that’s where the assistant editor plays a great role of cleaning up the codification. But in terms of the director and the editor codifying, we try to be disciplined and as clear as possible and then as the process continues, you keep cleaning the codes. But if you have a subclip and you have four or five columns – code 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and I make the selects and I have put two or three codes, I can just add them in those columns. Then on the side I have a list of all of the codes that we have assigned.

HEREDIA: Ohhhh! Yeah! Very important. I actually do a lot of design in my off-line process. I know that eventually a sound designer will come in and apply their art, but I want to make sure that I am building a good map of what I want and how I want things in terms of the kinds of sounds that I want and where those sounds should go. I build the concept but I don’t do the work of cleaning or EQing the sound or finding additional layers of ambience or sound effects. I build the layers related to dialogue, and production sound, obviously music and sometimes I might add a few effects that might be critical for the viewing experience so when I deliver the off-line project to my sound editor, they know exactly what I meant. This whole thing is about communication and it’s about the next person in this collective construction of a film knowing what the editor wants. That’s the same relationship that you as an editor have with the director. You are trying to construct something based on the communication and understanding that you have from the person who brought the idea and the footage to you.

HEREDIA: I think a lot about editing as if I was preparing a meal. I don’t believe you make a potato and tomato soup and put the potato at the end, because it never mixes the way those two things should mix. So I work with music as I go. The way I work with composers – usually I work with composers – but sometimes I have to work with libraries of music. I build a bin of samples of the composer’s work. They provide me with a bunch of cues of their own music, either things I can use or things I cannot use (because they belong to other projects) but that will serve as templates.

HULLFISH: I know many of the films you do you don’t need to worry really about hitting an exact show time, but on Toucan Nation, this is broadcast in the US, so you need to hit a specific time, right?

HULLFISH: (laughs)

HEREDIA: (laughs)

HULLFISH: So how do you negotiate that? Do you just tell the story you want to tell and now you have something that is an hour and 15 minutes or two hours and a half? Then comes the painful process of trimming it down.

HEREDIA: It’s an interesting challenge: how do you squeeze it to just get the essence? And sometimes, hopefully, if you do a good job, it makes it better because it obliges you to think harder on how not to lose the essence of the story as you have to trim it down. Sometimes it’s not good for the film, but sometimes you can make it good. It’s a challenge… I hate it, because I come from the culture of HBO where it doesn’t matter what length it is, but if you work for any other place – I’m working for Discovery now, but everybody that has commercials needs to have an exact time. (laughs) Not my favorite thing.

HEREDIA: I can’t remember. Maybe because I hate to remember the things I don’t like. But I don’t remember how I got to it except that it is like fine surgery. Sometimes it’s as easy as pulling a whole scene. But most of the time it’s not like that. You go to a scene and take one line here, 10 frames there. It’s just about trimming just a little so you don’t lose anything important. You just take fat and the fat might be very, very thin, but you keep shaping and shaping and shaping.

HULLFISH: Do you remember how long the first assembly of “Toucan Nation” was?

HEREDIA: It probably was an hour and a half.

HULLFISH: And had to get down to 42 minutes or something?

HEREDIA: Yeah.

HULLFISH: What was the schedule of shooting this and editing this?

HEREDIA: My main photography happened through six months. Then the last eight months I probably did five more shoots. But the balance between shooting and editing shifted. The first six months was mostly shooting and some editing. Then the last months I switched to mostly editing and as I discovered things that I needed or new developments were happening, I would go back and continue shooting.

HULLFISH: I think that’s everything I have. Thank you so much for talking with me.

HEREDIA: Very good questions, Steve! Thank you for the opportunity.