Jan Kovac started his editing career re-editing shows, like HBO’s “The Sopranos” from their original HBO broadcast down to a syndicated TV length at the L.A. post-production house, Five Guys Named Moe. While there he met Glenn Ficarra. Ficarra and John Requa directed “Crazy Stupid Love,” “Focus” and “Whiskey Tango Foxtrot.” Jan and I spoke via a video Skype call. I mention this now, because it factors into the article later.

HULLFISH: So you’ve cut two movies on FCP-X now.

KOVAC: “Focus” and now “Whiskey Tango Foxtrot.”

HULLFISH: What did you use before FCP-X?

KOVAC: Mostly Final Cut 7. Avid also, but I haven’t cut on Avid since 2011. I’m on lynda.com re-learning as we speak. In 2012 I started to do small file-based projects in FCP-X.

HULLFISH: Talk to me about organizing those movies in FCP-X.

KOVAC: Final Cut 10 has key-wording. It doesn’t have bins at all. You could maybe call them bins, but multiple clips or multiple parts of one clip can belong to more than one keyword collection. So if you have a keyword for John’s faves or my faves or Glenn’s faves, then I can have one take belong to all three of them and be searchable. So the take or the part of the take or multiple parts of the take don’t just belong to one “bin.” I hesitate to call them bins.

HULLFISH: So describe to me how your assistants set up your dailies for you to edit.

KOVAC: I have them use the reject function and reject regions before “action” and after “cut.” And if we shoot a series without cutting, then they reject the dead space between takes. The dailies can then be viewed without those regions, so everything shows up starting on “action” and ending with “cut.”

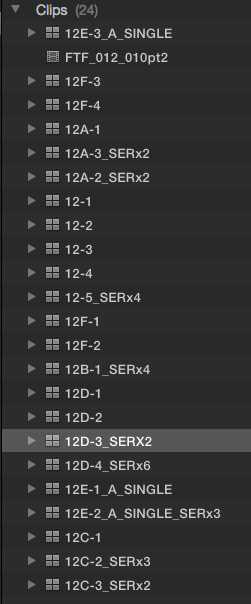

HULLFISH: So if the footage isn’t in a “bin” then how do you track down all of the shots for a specific scene? For example scene 12. (We’re trying to give access to the full resolution images, but this updated site is … new to us.)

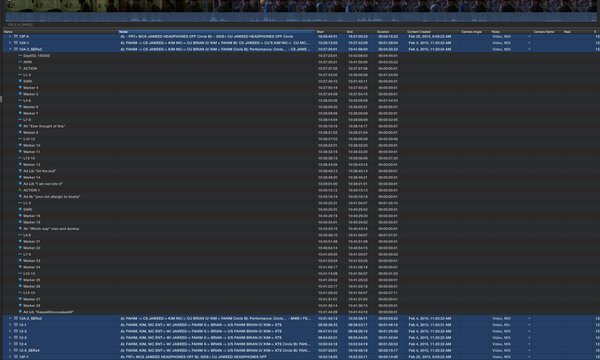

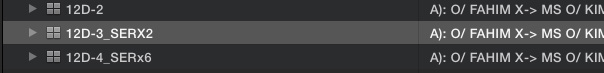

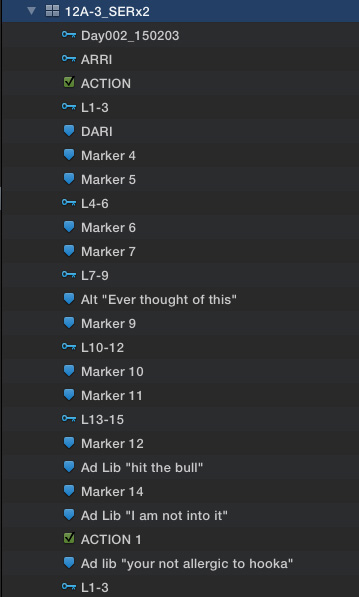

KOVAC: They would show up in my Scene 12 event and they are broken down into two views: list view which shows the entire take on top and underneath of it I have my assistants input the scripty’s notes (script supervisor’s notes) in the Notes field, which is automated. So I can quickly see, for example, in this take, 12-d take 3, it’s a series of 2 and my A camera is over-shoulder Fahim, crossing over to medium shot of Kim, moving into a full shot including Brian and that it’s a circled take and my B-cam is a POV of Kim’s that is roving around. That’s in the list view. I can check immediately what’s on it – what the camera moves are in my notes field, plus I see that individual clip with audio waveform on top which I can skim through. Or I can use the film-strip view which let’s me see the entire clip that you can skim through and choose regions and mark regions, so that’s the two windows I work in. We are trying to find an answer to Avid’s ScriptSync because John and Glenn really like to audition performances later in the process. They’ll ask to see all of the takes of a given line and need quick access to it.We came up with this keywording system where we number the lines of dialogue in a scene and those numbers re-set with every scene. So we keyword “L1-3”, then “L4-6” then “L7-9” and “L10-12.” Then we have these regions that can be easily previewed or auditioned …. I see you are confused. Let me send you some screengrabs.

HULLFISH: I kind of like doing these interviews on video Skype! I’ve done three of them with video – you and Lee Smith and Joe Walker. It’s nice you can see my confusion. OK, I have one of the screengrabs up.

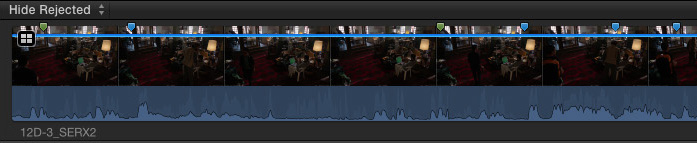

KOVAC: This is the film-strip view. I can squeeze all takes into one-frame representation or I can have them as long as the take is and play or skim through them and select parts I like. It’s easy to go through the scene really quick. I think it’s a great visual way to absorb the coverage you got. And if you see the highlight on the left side that says, “L1-3” those are the keywords that would represent the regions indicating lines 1-3 of that scene.

HULLFISH: So what do the little blue dots represent on the thumbnails?

KOVAC: Those are markers. If you go to the top clip, you see the first clip – the green marker is my “action” marker. That’s where action starts. My assistants mark in the series where each “action” is. The blue markers are the lines. So in the list view those markers correspond to keywords for each three-line set of dialogue in each scene. (above – Jan with First Assistant editor Kevin Bailey.)

KOVAC: Those are markers. If you go to the top clip, you see the first clip – the green marker is my “action” marker. That’s where action starts. My assistants mark in the series where each “action” is. The blue markers are the lines. So in the list view those markers correspond to keywords for each three-line set of dialogue in each scene. (above – Jan with First Assistant editor Kevin Bailey.)

HULLFISH: So you can jump to any line in any clip using keywords?

KOVAC: Correct. Or if I click on that keyword ,it’s going to filter the view and it will only show me those lines. If I’m auditioning line 5, I play that keyword and I see just that line for all of the takes.

HULLFISH: That’s very interesting. So I’m looking at 3:21:26PM screenshot. That is all of your coverage for that particular scene?

KOVAC: No. That’s just for lines 1-3.

HULLFISH: Ahhh. And the green markers mean “action” so we’re looking at maybe 12 takes or set-ups for lines 1-3?

KOVAC: Yes.

HULLFISH: Then you can roll through just that line for all takes. Interesting.

KOVAC: I can just audition those. Find the best take. For example if you click on 3:20:54PM, that shows me the coverage for the entire scene without selecting lines 1-3. This was something I wanted to change from “Focus.” On “Focus” I had my assistants select the region ending at the end of line 3 on the script, but the problem was that I could only see lines 1-3 and not the rest of the scene continuing on. It was basically like a subclip in Avid. So on “Whiskey Tango Foxtrot” we just mark an in on the first part of the line and no out.

HULLFISH: And every blue marker is a section representing three lines of dialogue and the green markers are “action.”

KOVAC: I’m looking for the list view that would explain it better. 2:23:37 PM. So this is the list view.

KOVAC: I still have my visual representation of the clip which is great. I can skim or play through it. I can see my waveforms. And then I have my script notes in the notes field, so you can glimpse at it and see in take 12a-1 we move in on Fahim for a close up… then we find Kim and Nick and that then camera moves to closeup of Brian over Kim.

HULLFISH: (laughs)

KOVAC: This is basically the organization we have at the beginning of the movie. Each scene has its own event and it’s in one big library. This time around we created small sequences or mini-reels so we could work not just within scenes and not in long reels, but in beats of three to six scenes. It was easy to share and It gave us a better sense of rhythm then working in individual scenes and it was easy to share with Glenn and John who are my co-editors.

While shooting, they are in the directing zone and I do most of the cutting, but once we’re into post we set up a room for John and Glenn. Glenn has a system. John has an extra screen and we basically start going through every permutation of collaboration there is. Sometimes Glenn cuts and I cut and John works with him then he works with me. Sometimes they both work with me. Sometimes I do notes on their scenes. Sometimes they do notes on my scenes. It changes throughout the process and moves slowly towards a more traditional director/editor relationship at the end.

HULLFISH: With that screenshot 2:22:37 there are a bunch of icons with four little boxes. Does that mean they’re all multicam?

HULLFISH: With that screenshot 2:22:37 there are a bunch of icons with four little boxes. Does that mean they’re all multicam?

KOVAC: Yes. That means multicam. Most of the film was multicam. I’d say, more than 90 percent. Same as “Focus.” I think Final Cut’s multicam interface is the best while in it and is great for intuitive editing, but it gets a bit complicated when you get into split screens where you want to pace up the performances and join performances from different takes together with a split.

HULLFISH: So when you’re trying to do those specific tasks using a multi-cam, Final cut doesn’t handle those well right now?

KOVAC: For Optical Flow and planar tracking the multicam does not function as single cam which means I can not track on that shot. I can not copy my tracking markers from a single shot to multi or do multiflow respeeds. I have to match back to a single cam, which gets cumbersome. Also, we love the Audition tool in FCPX where you can cut four different versions of a take into your timeline and preview it within the context and cycle through all the versions. It’s an amazing tool, but that doesn’t work with multicams. It would be great to have these tools available in the multicam world.

HULLFISH: Especially since almost every movie made nowadays is shot multicam. Everybody is shooting with at least two simultaneous cameras.

KOVAC: That’s true. Absolutely.

HULLFISH: So, I’m looking at screenshot 2:23:37PM and I see that you’ve got the 12d-3_SERX2 is highlighted down in the list view. Does that mean that the waveform and thumbnails along the top is that shot?

KOVAC: Yes. That is correct. You just do up arrow and down arrow and that will walk you through the other cameras. If you click on the arrow on the left it opens the markers and the descriptions. Look at 2:23:52PM. That clip is open with the information marked and prepped by the assistants.

HULLFISH: So all the markers are the markers that jump you to certain lines?

KOVAC: The key symbol is a keyword. It shows that it was shot on day 2 and the time. It shows you it’s ARRI. Then I have my action mark. SERx2 means series and that I have two “actions” in that series. It’s represented by two green markers: action and action1. Then I do have Line 1-3, then marker 4, marker 5, so you can see I have three markers for lines. There is also an alt that wasn’t in the book. Can you see that there’s an adlib under marker 12?

KOVAC: The key symbol is a keyword. It shows that it was shot on day 2 and the time. It shows you it’s ARRI. Then I have my action mark. SERx2 means series and that I have two “actions” in that series. It’s represented by two green markers: action and action1. Then I do have Line 1-3, then marker 4, marker 5, so you can see I have three markers for lines. There is also an alt that wasn’t in the book. Can you see that there’s an adlib under marker 12?

HULLFISH: “You’re not allergic to hookah?” That’s really fascinating to me. It would take some getting used to, but I can definitely see the power of this. But just like with ScriptSync in Avid, this is going to take some serious prep for the assistants. It’s a lot of man-hours to get this ready.

KOVAC: If we shoot on Monday, to get all this prepped, I would get it Tuesday evening at the earliest or Wednesday morning. So it’s a full day of prep to get all of this done. During production, I had two assistants and an apprentice and a P.A. We were also syncing dailies. So they had that on their plate also. (above – Kevin Bailey 1st AE)

KOVAC: If we shoot on Monday, to get all this prepped, I would get it Tuesday evening at the earliest or Wednesday morning. So it’s a full day of prep to get all of this done. During production, I had two assistants and an apprentice and a P.A. We were also syncing dailies. So they had that on their plate also. (above – Kevin Bailey 1st AE)

HULLFISH: So they were getting double-system sound from production audio and camera department stuff. Was stuff getting transcoded?

KOVAC: One of the reasons we chose Final Cut was that we wanted to work in highest possible resolution, basically in the O-neg resolution. The bulk of the work is Alexa. ARRI and Apple developed a new codec which is 4:4:4:4XQ which allowed us to completely skip ARRI-RAW. Even for the green screens. Everything was shot in ProRes. The big advantage was the VFX workflow and the fact that it looks the same on our system as it’s going to look in the theater, only it hasn’t been colored yet. The only change between the dailies that I am looking at and the O-neg is that there is a CDL (color decision list) value burned in on set, but there is no LUT on it. The LUT is being applied as we go in Final Cut.

KOVAC: One of the reasons we chose Final Cut was that we wanted to work in highest possible resolution, basically in the O-neg resolution. The bulk of the work is Alexa. ARRI and Apple developed a new codec which is 4:4:4:4XQ which allowed us to completely skip ARRI-RAW. Even for the green screens. Everything was shot in ProRes. The big advantage was the VFX workflow and the fact that it looks the same on our system as it’s going to look in the theater, only it hasn’t been colored yet. The only change between the dailies that I am looking at and the O-neg is that there is a CDL (color decision list) value burned in on set, but there is no LUT on it. The LUT is being applied as we go in Final Cut.

HULLFISH: So you’re seeing it LUTed to REC-709?

KOVAC: Yes. Final Cut translates it directly to REC-709 once you apply the LUT. But it does not disturb the clip. It stays LOG-C all the way through.

HULLFISH: So these clips in the screengrabs – in your system – are actually referring to the ARRI ProRes files that were being recorded on-set?

KOVAC: Yes. The three big advantages of editing in the highest resolution and in ProRes from the get go is that all your DCPs that are created throughout the process (for screenings) look amazing and you get a much better feedback since there is a lesser amount of technical imperfections your audience can bump on. And the second really good thing was that since we didn’t have to deal with ArriRaw, editorial could carry a copy of the o-neg for our in-house vfx crew. We had 1200 VFX shots – it’s hard to create Afghanistan in New Mexico, so there was a lot of small stuff to do. We would not be able to do that if we had to go to outside vendors, but we had a lot of VFX artists in-house – at some point 20 of them – and I carried the O-neg on my SAN. I had one chassis just for the O-neg, so they were working straight from that with us. They figured out a color pipeline and there was no pulling frames. No waiting for the DI house to give it back to you. No dealing with different vendors. We could see shots immediately and making small changes as we went. It was a big financial saving, but for me, it was mostly creative because it gave us more time on temps and all the temps we worked on – even in Final Cut – were a real step towards the final. It wasn’t like you were just working on a temp and threw that work away. When you worked on a temp, as it was getting approved, it was becoming the final.

And the third reason for working this way was, that it allowed Glenn and John to shoot faster. They didn’t have to worry about a microphone being in a scene for example. They could concentrate on getting the performance they wanted since they knew we could take care of stuff like that later.

HULLFISH: How were you doing hand-offs to VFX then?

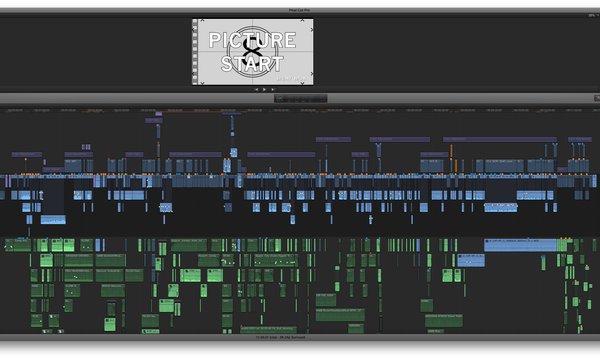

KOVAC: That was my assistants, but I know the back part. They would cut it back to me into my timeline. Kevin Bailey was our first assistant and he could tell you. It worked great. But for basics, if you go to the first screengrab with the Paramount logo on it

HULLFISH: 1:12:46.

KOVAC: See the orange markers? Final Cut has three kinds of markers. You can’t change colors on them. It would be nice if you could. But they are all searchable. But the red ones are me leaving notes for my assistants on stuff to do. Once they’re done they become green markers. The blue ones I already told you about. The orange ones are chapter markers which we are using to mark VFX with. You can see the stuff that’s above them are the VFX shots that are cut in over the originals.

HULLFISH: How long is this timeline?

KOVAC: That’s a 20 minute reel. If you go to the next one I can explain about the roles.

HULLFISH: Ah yes. Roles. (from FCP-X manual: “Final Cut Pro assigns an audio role (Dialogue, Music, or Effects) to the audio portion of all clips on import. Role assignments make it easy to organize clips by audio type, but their most powerful benefit is the ease with which you can export separate files (called media stems) from Final Cut Pro for all dialogue, music, or effects clips. This process is often used when delivering stems to match broadcast specifications or when handing off stems for mixing or post-production.” 2:22:41 screenshot.

KOVAC: I have our assistants mark everything that comes in with a role. You see on the left a dialogue role. Underneath that, every microphone has its own role. You have Afghan, Angry woman, boom, and so forth.

HULLFISH: This is off to the left side where it’s blue it says “dialogue.”

KOVAC: If you organize tracks they’re by numbers onto which you put your content and you have to decide which number corresponds with what microphone. Here in Final Cut it’s just organized based on content. It’s not organized with tracks, it jumps all over. But you see how I have the dialogue selected? See how it’s highlighted in the lighter shade of green? It’s really easy to orient yourself.

HULLFISH: So the dialogue clips are actually spread out all over the place, but because they have been assigned to a role, that doesn’t matter?

KOVAC: My assistants hated me for it, but when I’m working I like to put some stuff above picture because it doesn’t matter in the Final Cut, but they couldn’t get over that so I started putting it below. (right – Assistant Esther Sokolow)

KOVAC: My assistants hated me for it, but when I’m working I like to put some stuff above picture because it doesn’t matter in the Final Cut, but they couldn’t get over that so I started putting it below. (right – Assistant Esther Sokolow)

HULLFISH: That’s all well and good until you have to deliver it to an audio mix house. So you go through a 3rd party app to get it to a mixer?

KOVAC: Yeah. It goes through X2Pro (http://www.x2pro.net/). It’s plugin which basically takes the roles and assigns them to tracks. So FX would be living on tracks 14 to 18 and what not. And it creates your AAF for ProTools. If you go to 3:23:17PM… here you see the waveforms. That’s more the way it looks when I’m working on it. I love in Final Cut that it edits in subframe – I believe an 1/80th of a second. It’s really great for cutting music. That makes a huge difference. Plus if you would select part of the clip and wanted to duck, you grab the solid line in the middle which represents your level, drag it down and duck it and it automatically adds the keyframes, so it adds little two frame fades on each side so you don’t have to click and put keyframes on it. Then you can make the fades faster or slower. When I was working in the trailer it was LCR (left, right center), with all dialogue center. Once we landed in post we worked in 5.1 Kevin, my first (assistant) did most of the sound work behind me. And if you go to the last screenshot – 3:27:41 –

HULLFISH: But back on 3:23:17, you’ve got dialogue selected. So Dialogue is the role or each individual mic is the role?

KOVAC: You could go down to the microphone, but here all dialogue is selected as a role. You see the production that’s part of the picture that’s lighter blue…

HULLFISH: So above the green is a blue section. And above that is kind of a purple section.

KOVAC: Yeah, the purple section is the color adjustment. That’s a color layer for making the DCPs.

HULLFISH: So there’s the green section below and you said that the light green stuff is the dialogue.

KOVAC: Then production that is synced with the picture is part of the blue clip – that’s lighter blue, that’s dialogue, you can see it has a waveform. There’s a Paramount logo at the beginning with music which is not dialogue, so it’s darker blue, it’s not lighter blue.

HULLFISH: So the lighter blue stuff is the dialogue?

KOVAC: Lighter blue and lighter green both.

HULLFISH: So what’s the difference between the blue stuff and the green stuff?

KOVAC: The blue stuff is tied to the clip and the green stuff is from some place else moved underneath the picture.

HULLFISH: Wow. That’s a lot of moved, unlinked dialogue!

KOVAC: That was a party scene, so it’s people singing and multiple layered voices.

HULLFISH: Holy smokes. That’s pretty elaborate. I don’t want to beat FCP-X to death, although it’s fascinating to look at. So this is a comedy.

KOVAC: It’s a war comedy set in Afghanistan at the time when we went to war with Iraq so there’s a shortage of journalists covering the war and Tina Fey’s character volunteers to go there and finds herself in the world she’ knows little about and it’s about how she reacts to it and adjusts to it. It’s based on a book by Kim Barker who covered Afghanistan during that time.

HULLFISH: Performance is so critical to comedy. What are you doing when you watch the dailies. Are you watching the dailies by yourself or with the director and what are you picking up from that and trying to make determinations about?

KOVAC: We don’t screen dailies as a group. Our dailies come on iPads. Each department head gets one and the producers, but on “Focus” Glenn and I shared a house in New Orleans and on “Whiskey Tango Foxtrot” we shared a house in Santa Fe and lived in the same hotel in Albuquerque. So Glenn and I would watch dailies at night and talk about spots. But I would cut a scene from what I would think was the best and show it to the guys the next day. The reason that I’m cutting in the trailer on set is because of my trailer is next to their trailer. So they just jump over and spend 10 or 15 minutes each day looking over my scenes and kind of figuring out which tone to give it. Obviously this kind of war comedy, the kind that’s rooted in realism, is going to have a lot of tonal shifts. And the guys love to work with tonal shifts. I don’t know if you’ve seen “Focus”, “Crazy Stupid Love” or “I Love You Phillip Morris” but their work tends to be a little darker or have more emotional beats and for that they shoot similarly as Spike Jonze. They bracket the performances very wide so they can go from comic to really serious in the cutting room later and shape the story and the emotional beats the way they want.

KOVAC: We don’t screen dailies as a group. Our dailies come on iPads. Each department head gets one and the producers, but on “Focus” Glenn and I shared a house in New Orleans and on “Whiskey Tango Foxtrot” we shared a house in Santa Fe and lived in the same hotel in Albuquerque. So Glenn and I would watch dailies at night and talk about spots. But I would cut a scene from what I would think was the best and show it to the guys the next day. The reason that I’m cutting in the trailer on set is because of my trailer is next to their trailer. So they just jump over and spend 10 or 15 minutes each day looking over my scenes and kind of figuring out which tone to give it. Obviously this kind of war comedy, the kind that’s rooted in realism, is going to have a lot of tonal shifts. And the guys love to work with tonal shifts. I don’t know if you’ve seen “Focus”, “Crazy Stupid Love” or “I Love You Phillip Morris” but their work tends to be a little darker or have more emotional beats and for that they shoot similarly as Spike Jonze. They bracket the performances very wide so they can go from comic to really serious in the cutting room later and shape the story and the emotional beats the way they want.

HULLFISH: Explain to me a little bit about that bracketing process.

KOVAC: You get the actors to do lighter takes and you get them to do a darker or more emotional version of the same scene and everything in between. You don’t want to get stuck in the cutting room with just one way to edit the scene.

HULLFISH: That either relies a lot on you or the director to determine at any given story point which way you’re going to play that.

KOVAC: That’s correct. I am wrong a lot.

HULLFISH: (laughs)

KOVAC: But that’s the process. That’s what replaces the traditional dailies process. We are all close friends , so it’s easier for me to find the right tone or note from the get-go than it might be for someone else. But still, as I said, I can be wrong a lot. Sometimes I make a couple of versions, just to see what they might want from a scene and then we can narrow it down. It’s really rewarding to work with Glenn and John. These guys are amazing creatively. They give you such a feeling of ownership. I won the lottery twice. Once when I got my citizenship and second when I was able to edit “Focus” and continued working with them on Whiskey Tango Foxtrot.

HULLFISH: Tell me a little bit about hitting the lottery the second time. What gave someone the confidence in you to give you the reigns for “Focus?”

KOVAC: Well, it’s kind of miracle that they did. Glenn and John and I worked on each others shorts way back so we were kind of basing the trust on that and the years we spent together as friends. I’ve spent a lot of years re-cutting TV series for syndication. Mostly Sopranos and Curb Your Enthusiasm and Six Feet Under. That was mostly my school, but I think the fact that I could do it was because the guys wanted to be more hands on. Glenn wanted to cut and I liked the idea of us editing together. And it was because with FCP-X no one else would work on it. They asked some other editors first, but supposedly I was the only one who said, “Let’s do it!” Everybody else said, “Why don’t we cut with the industry standard, right?” So that was my in. And our associate producer, Jeffrey Harlacker believed in me and I had a great interview with Mark Solomon at Warner Brothers the head of their feature post, so he believed in me too. It’s catch-22, right? They won’t let you work on one until you’ve done one.

HULLFISH: How did that collaboration work with the three of you?

KOVAC: I’m basically doing second and third note passes throughout the production to narrow down which way we want to go and once we get to post, Glenn starts cutting alongside me. (Glenn pictured left with a hacked AC unit for edit room) At the start of that process we break the movie into short sequences – mini-reels – we had 24 of them to start with which gives us flexibility to share and cut and move between. So let’s say the first couple of days they would give me notes, I would start cutting my scenes, Glenn would grab a few. They would call me in. I would give them my notes, then Glenn is maybe cutting in his room and I’m cutting in mine and John is jumping between us giving us notes, working with both of us, or looking through takes. Then they would maybe give me notes on stuff that I cut and come back two days later and I would show it to them. What I found very refreshing was Glenn and John doing their own notes instead of me doing it because it keeps you fresher. You get away from the scene for a day or two and see it with fresh eyes with a different take on it. You see it in a better light and you’re more objective in judging what’s working and what’s not working and it works the same way for them. They are not spending a day locked in on one scene and losing perspective. That’s the most precious commodity in the cutting room.

KOVAC: I’m basically doing second and third note passes throughout the production to narrow down which way we want to go and once we get to post, Glenn starts cutting alongside me. (Glenn pictured left with a hacked AC unit for edit room) At the start of that process we break the movie into short sequences – mini-reels – we had 24 of them to start with which gives us flexibility to share and cut and move between. So let’s say the first couple of days they would give me notes, I would start cutting my scenes, Glenn would grab a few. They would call me in. I would give them my notes, then Glenn is maybe cutting in his room and I’m cutting in mine and John is jumping between us giving us notes, working with both of us, or looking through takes. Then they would maybe give me notes on stuff that I cut and come back two days later and I would show it to them. What I found very refreshing was Glenn and John doing their own notes instead of me doing it because it keeps you fresher. You get away from the scene for a day or two and see it with fresh eyes with a different take on it. You see it in a better light and you’re more objective in judging what’s working and what’s not working and it works the same way for them. They are not spending a day locked in on one scene and losing perspective. That’s the most precious commodity in the cutting room.

HULLFISH: Let’s talk about structure. How was the movie different from the script?

KOVAC: There were a bunch of scenes that were great, but they were stubborn, they didn’t want to cooperate with us and at some point you just leave in the movie what the movie wants. You start with the “kitchen sink” cut which was three hours and we got it down to an hour and 52 minutes with credits. You’re taking the time out as you go, but the time being cut out is not the goal; it’s a side-effect, because you are really trying shape the movie on micro and macro level. Working on the balance of the tone was really fun but it took some time to get it right.

HULLFISH: But you were able to get to that point because of the bracketed performances?

HULLFISH: But you were able to get to that point because of the bracketed performances?

KOVAC: Yes. You are not stuck in comedy or you are not stuck in drama. It’s pretty amazing to get that kind of a performance coverage the guys shot.

HULLFISH: What kind of re-structuring did you do on this film, or if you want to go back to “Focus?”

KOVAC: I think it was probably getting Kim (Tina Fey’s character) in the action in Afghanistan and into the thick of it as fast as we could. And then shaping the moment when you find out she’s “all in” in that world and that she’s not an outsider any more. I think getting to that portion of the movie without breaking everything else was a bit of a puzzle.

KOVAC: I think it was probably getting Kim (Tina Fey’s character) in the action in Afghanistan and into the thick of it as fast as we could. And then shaping the moment when you find out she’s “all in” in that world and that she’s not an outsider any more. I think getting to that portion of the movie without breaking everything else was a bit of a puzzle.

HULLFISH: Let’s talk about your approach to cutting a scene? Like there’s a scene with Tina Fey and a blonde war correspondent where they’re joking about Tina being “a ten.”

KOVAC: I’d read the script and highlight the beats in the scene – one or two major beats in the scene. Than I find that section and I look at all the takes for that section of the beat. I find the best take, cut it in, then build everything around it. So it either culminates on that beat or moves from that beat to a crescendo. I build around it in chunks. I try to move through the first few passes instinctually. But my thinking is done before-hand when I am looking for the beats – the “lean forward moments.” So I start with those and build around.

HULLFISH: It sounds very architectural. Many editors start at the beginning and move forward. Others agree with you and find critical beats in the middle of the scene where “this is the moment” and this is the perfect take and angle which illustrates that moment, then you have to work forward and backwards from that moment.

KOVAC: I think it’s important to work that way with so many tonal shifts because you can start really light or find some very funny joke in the beginning but by the time you get to the moment important to your character and story, it may be totally off and feel like it doesn’t belong into the movie.

HULLFISH: The audio timeline you showed us seemed very complex. Talk to me about how important it is for you to do a fine sound design while you’re editing. How much does the sound design influence how well they sell your visual cuts?

KOVAC: It definitely affects tempo, rhythm and pacing of your cutting. It’s important for John and Glen to be as close to being done from the get-go. I try to present to them the “final” look and the “final” sound from the first cut. You don’t want them to jump through hoops to feel whether the scene is good or not or what needs to be changed. So it’s better to put extra work in to get yourself there and get the directors there. You’re trying to make it as easy on them as possible to stay in the scene. My first (assistant) did a great job on the sound part of it, he worked with Walter Murch, so he had good training. He worked on sound behind me and we were able to do a lot of sound design and mixing from the time I was cutting in the trailer on location.

HULLFISH: What about music for you? What do you use for temp?

KOVAC: On “Focus” we did not cut with any temps, but we had about 60 minutes edited, our composer Nick Urata came to my trailer and we watched it and talked about it with John and Glenn and he started flashing out some ideas and started feeding us his music. John and Glen are extremely good with music. John has a great ear. Glen used to be a drummer and he cuts music really well. Both of them have a good taste and are really good with placing music with the right feel. Nick Urata was our composer on “Whiskey Tango Foxtrot” also. He did an amazing job, but we used temps on WTF. We worked with Jason Ruder for both films as music supervisor. He’s our music supervisor and he works closely with John and Glenn, feeding us with plethora of cues. We also worked with Phillip Tallman for temp music editing, but only for a short while because he had to go work on “Joy.” I think Billy Fox worked with Jason Ruder on “Straight Outta Compton.” Then we had David Mezner, who finished up cutting the music for us. I must say, I became much better at cutting music by working with Glenn and john. It was one of the great things I learned while cutting alongside them.

HULLFISH: Winning the lottery again. (laughs) What about VFX? You said there was a lot of VFX in this. How much does that affect your editing?

HULLFISH: Winning the lottery again. (laughs) What about VFX? You said there was a lot of VFX in this. How much does that affect your editing?

KOVAC: A lot of the VFX were just green-screen TV coverage comps. A lot of split screens, re-speeds, stuff like that. So if I have time, I do that. If not, I have my assistants do it. The bigger stuff we temp in Final Cut and some of that actually made it into the final that were made in Final Cut thanks to us working in the O-negative resolution. There is, for example a shot of a person talking on Skype, but it’s not straight up, so you add the user interface and then Tina’s face in as a reflection. So things like that we’re creating in Final Cut and it has to look great. It can’t take you out of the story.

HULLFISH: Talk to me a little bit about those splits you mentioned. You aren’t talking about a split screen like the transitions in the TV show “24” right? You mean you’re doing a split on a performance to either combine the best of one person’s performance on one side of the screen with the best of another person’s performance on the other side of the screen, or using the splits to retime the performance, right? Because when you’re looking at two people in a scene together, that’s not always just a simple, single take.

HULLFISH: Talk to me a little bit about those splits you mentioned. You aren’t talking about a split screen like the transitions in the TV show “24” right? You mean you’re doing a split on a performance to either combine the best of one person’s performance on one side of the screen with the best of another person’s performance on the other side of the screen, or using the splits to retime the performance, right? Because when you’re looking at two people in a scene together, that’s not always just a simple, single take.

KOVAC: It can be as simple as what happened in one scene, where the head of the network is talking to Tina as she’s walking into the shot, but in the best take for the actor sitting behind the desk, Tina was already standing in the shot. So we split it and had her walk in from a different take. That’s a very simple case.Then there are more complicated examples that are more performance driven, not just technical or timing.

HULLFISH: I taught an editing class where I gave everyone four or five camera set-ups and takes of Gary Sinise performing a scene from “Streetcar Named Desire.” All of the editors cut the scene before the class and then we all watched each other’s cut. It was very informative to see 20 really good editors cut the same scene. But I remember one guy, his timeline was filled with special effects – this was on Avid – and you could see the effects icons on every single scene. I was trying to figure out why this guy would have all these effects on a simple dramatic scene. It turned out that he was splitting the performances to get the best performances and to enable him to make better continuity edits on either end of the wide shots. It worked great.

KOVAC: It’s a great help. All the pull-ups you can do and Fluid Morphs or Optical Flow tricks. Those are amazing because there are a lot of pauses and you have to pick up the pace a lot of times and you don’t want to do it just with cutting. The hard thing with splits in this movie was that it was all hand-held, so you had to track both sides and it was harder to match.

KOVAC: It’s a great help. All the pull-ups you can do and Fluid Morphs or Optical Flow tricks. Those are amazing because there are a lot of pauses and you have to pick up the pace a lot of times and you don’t want to do it just with cutting. The hard thing with splits in this movie was that it was all hand-held, so you had to track both sides and it was harder to match.

HULLFISH: How much do you feel you’re shaping the performance in editing and how much are you being the steward of the performance, or does it depend on the scene?

KOVAC: It depends on what happens in the take. Sometimes you want to just stay the f— out of actors’ way and keep what they did and sometimes you need to create something that did not exist before. So they are both important. I think it’s more important to understand when to stay away from ruining a performance. (below – Jan and Nick set up the remote editing trailer)

HULLFISH: Let’s talk about how the editor is a storyteller. I think so many movie goers think that the script is the story and the editor just follows that, but that’s not true.

KOVAC: It’s a living thing. You go from a blueprint to a house. When you’re building it sometimes you find it works better if you move the bathroom downstairs or take out a wall. I remember a scene where an Afghan fixer for Kim is reading a O magazine as a comical beat as it was written in the script two-thirds into the movie and Kim was responding to him reading it. But it seemed too on-the-nose at that point, so we cut it earlier, in front of a different scene and then the callback to the joke worked better and was more effective.

HULLFISH: You were even affecting story by choosing those bracketed performances to modulate the tone.

KOVAC: I think that comes from our conversations with Glenn and John and knowing what they would like to get out of the material. They shoot a lot of great improv. When you start using that stuff, it can take you in a different direction from what was written. You might be gaining some nice moments, or a different look at the scene, enriching what was on page, but you don’t want to stay too far. They are great at getting improv and working with it in the cutting room.

HULLFISH: Pacing and rhythm in a comedy… How are you deciding when to cut and are you consciously deciding on tempo? Joe Walker said he consciously used leaps and jumps in time just before and after long, held shots to make the impact of them greater.

KOVAC: I usually start with instinctual cutting, based on the prep I mentioned earlier, and perhaps use some kind of a technique later if needed. I cut with my gut, which is big. (laughs) Then if it doesn’t work, I try something else. Shoot from the hip first, to get the scene into some basic shape, then see where it lands and start refining, and refining. Or throw it all out and begin agin.

HULLFISH: (laughs) I love it. Can you walk me through editing these two scenes?

KOVAC: We are establishing Kim and Tanya’s relationship in this short scene, and touching on how women are viewed in the war environment. All in a very funny way. This is a great example of actors being great and funny. The scene played great as written with just really straight-forward comedic cutting.

KOVAC: This clip doesn’t start with music that’s actually in the film, but I do love the montage we have here. It establishes Kim’s character and the boredom of her job in a quirky funny way and is so simple. It’s just five shots and you learn so much about her and hopefully chuckle a couple of times before you we get into the meat of the scene and learn about a gig opening in Afghanistan.

I’ve been an outsider all my life and I’m an outsider in the group of people you’ve interviewed, but I’m honored to be included. I know you mostly talked to me because I cut on FCP-X.

I’ve been an outsider all my life and I’m an outsider in the group of people you’ve interviewed, but I’m honored to be included. I know you mostly talked to me because I cut on FCP-X.

HULLFISH: That’s not true at all. I looked down the list of movies coming up in the next month and I saw “Whiskey Tango Foxtrot.” That looked like an interesting movie… it was the movie I was most interested in for the week it releases, so I checked to see who the editor was and what else you had done. I saw “Focus” which I knew was really the first movie to be cut on FCP-X and I figured that maybe you’d cut this one on it too, so I was excited to write about something different than the majority of people who cut on Avid, but it was not the reason… the reason was more Tina Fey!

KOVAC: Well, I’m very honored to be included. Plus it’s great to talk to another editor who is outside of Final Cut.

KOVAC: Well, I’m very honored to be included. Plus it’s great to talk to another editor who is outside of Final Cut.

HULLFISH: I actually did record another interview with an FCP-X editor already. Clayton Condit edited a movie called “Voice from the Stone” but that hasn’t come out yet, so I’m holding on to that interview. You should talk to him and you can compare notes. Then a couple of Premiere guys, Kirk Baxter and Julian Clarke.

KOVAC: Thanks for including me.

Stay tuned later this week for an interview with “Whiskey Tango Foxtrot” director on how and why he contributed to the editing of the film. If you are interested in reading the other interviews in the series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish for updates on upcoming interviews and other editing and color correction thoughts, wisdom and tips.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now