Thelma Schoonmaker, ACE is an iconic presence in the world of editing. Arguably, no name is known better in our industry. She has been teamed with Martin Scorsese in one of the longest-running director-editor collaborations in film, helping to shape cinema masterpieces such as Raging Bull, The Color of Money, The Last Temptation of Christ, Goodfellas, Gangs of New York, The Aviator, The Departed, Hugo, and The Wolf of Wall Street. She has won three Oscars for Best Editing and been nominated for four more, plus countless other nominations, awards and accolades. I had the honor to interview her for her most recent collaboration with Martin Scorsese, Silence.

HULLFISH: The audio design of the beginning of Silence is very strong and very different. What was the purpose or goal?

SCHOONMAKER: I think right from the beginning Marty wanted to prepare the audience for a more meditative film – to help them transition away from the kind of crash bang way movies usually begin these days. So we got permission to remove the sound for all the production logos at the beginning. At first, you hear hardly anything – maybe a little bit of wind over the logos – very low and then you realize that it’s the sound of insects. It’s actually cicadas, and they build until the logos end – and then there is a sharp cut to black and the sound of the cicadas continues to build over black and then the cicadas cut off suddenly as the title “SILENCE” appears on the screen – with no sound at all – dead silence. Many people have told me how much they love that opening. Then the first foggy image of the film appears with very quiet sounds of steam from the hot springs where priests are being tortured with scalding hot water in an attempt to get them to give up their faith. This mysterious opening allows the audience to calm down from our frantic lifestyles of today and just breathe and start to engage and think about the film – to start to feel it. That’s what Marty wanted. – to have the audience make up their minds about what they are seeing – not to tell them what to think with the use of a big score or loud sound effects.

SCHOONMAKER: I think right from the beginning Marty wanted to prepare the audience for a more meditative film – to help them transition away from the kind of crash bang way movies usually begin these days. So we got permission to remove the sound for all the production logos at the beginning. At first, you hear hardly anything – maybe a little bit of wind over the logos – very low and then you realize that it’s the sound of insects. It’s actually cicadas, and they build until the logos end – and then there is a sharp cut to black and the sound of the cicadas continues to build over black and then the cicadas cut off suddenly as the title “SILENCE” appears on the screen – with no sound at all – dead silence. Many people have told me how much they love that opening. Then the first foggy image of the film appears with very quiet sounds of steam from the hot springs where priests are being tortured with scalding hot water in an attempt to get them to give up their faith. This mysterious opening allows the audience to calm down from our frantic lifestyles of today and just breathe and start to engage and think about the film – to start to feel it. That’s what Marty wanted. – to have the audience make up their minds about what they are seeing – not to tell them what to think with the use of a big score or loud sound effects.

Here’s an exclusive premiere of a featurette about the editing of Silence. I’ll follow up some of the points in the video in the following interview with Ms. Schoonmaker.

HULLFISH: The featurette describes the pacing of the movie as a deliberate method to allow the audience to relax and allow them to engage with the movie on an emotional level.

SCHOONMAKER: The slower pacing of the movie is appropriate to the 17th century and to the country of Japan where things were very formal at that time. The subject matter of film which is about faith and doubt provokes profound thoughts and a slower pace is more conducive to that.

HULLFISH: You mentioned the word “formal.” How does that inform your editing to know that the film is formal or that the idea is formal?

SCHOONMAKER: Certain scenes were more formal than others. For example, there is a scene in a courtyard of the prison where Rodrigues (Andrew Garfield) is being questioned by the Inquisitor Inoue (Issey Ogata) and five other Samurai. It begins tight on six fans in the hands of the Samurai and then there is a montage of the Christian prisoners watching from a cage, and close-ups of Rodrigues and the other actors. But from that point on, as the interrogation develops, Marty shot the scene in a very formal way – a wide frontal of the six Samurai – quite a formidable shot of them seated in their beautiful kimonos representing the powerful authority confronting Rodrigues. And then a matching frontal wide of Rodrigues seated on the ground and the Interpreter sitting next to him on a stool – the lower position of Rodrigues indicating that he is considered not the equal of any of the Samurai. This is part of the attempt by the Inquisitor to break Rodrigues down, so he will give up his faith. The cutting here is very simple – wide frontal to wide frontal and then some two-shots and CUs and a side angle across Rodrigues to the Interpreter. But all the cuts are classically done. I remember on Kundun being impressed by how insistent Marty was that he know exactly how the six-year-old Dalai Lama was sitting in relation to his tutors. He wanted to know whether the young Dalai Lama was one foot above the tutors – or a foot and a half, so he could design his camera angles properly. Showing the young child towering over his elderly tutors was amusing, but it also showed the reverence with which the Dalai Lama, even as a youngster was treated.

HULLFISH: Perspective is obviously critical. Whose perspective did you choose to view that scene from?

SCHOONMAKER: Well, the perspective is split between Rodrigues taking in the Samurai, and the Samurai taking in this priest from a foreign land.

HULLFISH: Did you cut this in LightWorks?

SCHOONMAKER: Oh yes.

HULLFISH: What is it about LightWorks that you have come to love and why you haven’t embraced another NLE?

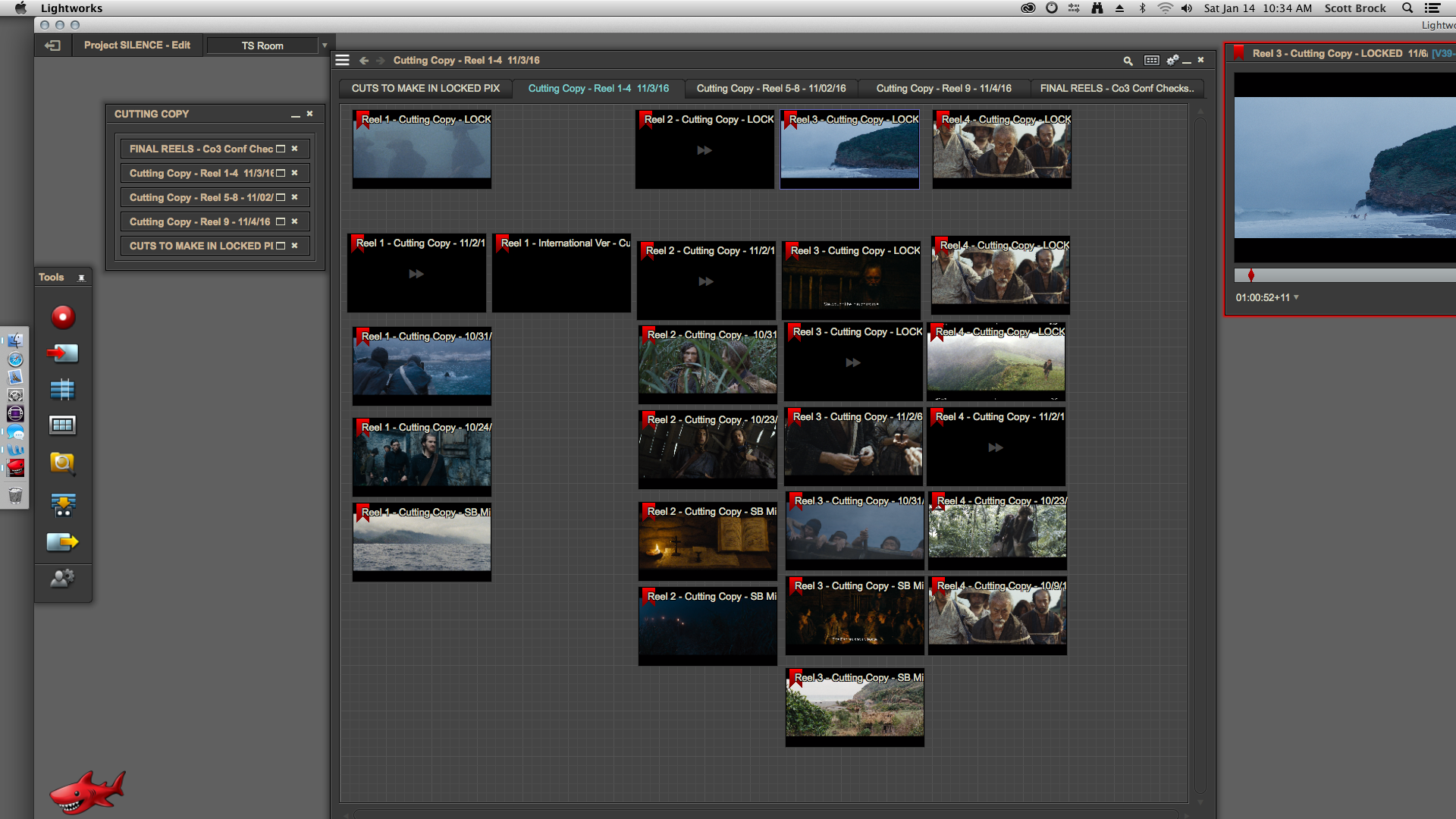

SCHOONMAKER: Well I was trained on it by Scott Brock, my associate editor when we began shooting Casino in Las Vegas. I was a very reluctant convert to digital editing at first, but Scott was fantastically patient with me and within a few weeks I was completely over my grumpiness and happily able to edit digitally. I was lucky that Scott was allowed to stay with me to help me adjust, and that he’s been with us ever since as a highly valued member of the editing team. He and I do all the temp mixes for our screenings together in the Lightworks. And Scott is terrific at building all the sound-tracks as the edit progresses. Only at the very end of post-production do we go to Soundtrack here in New York, where Tom Fleischman does the final mix.

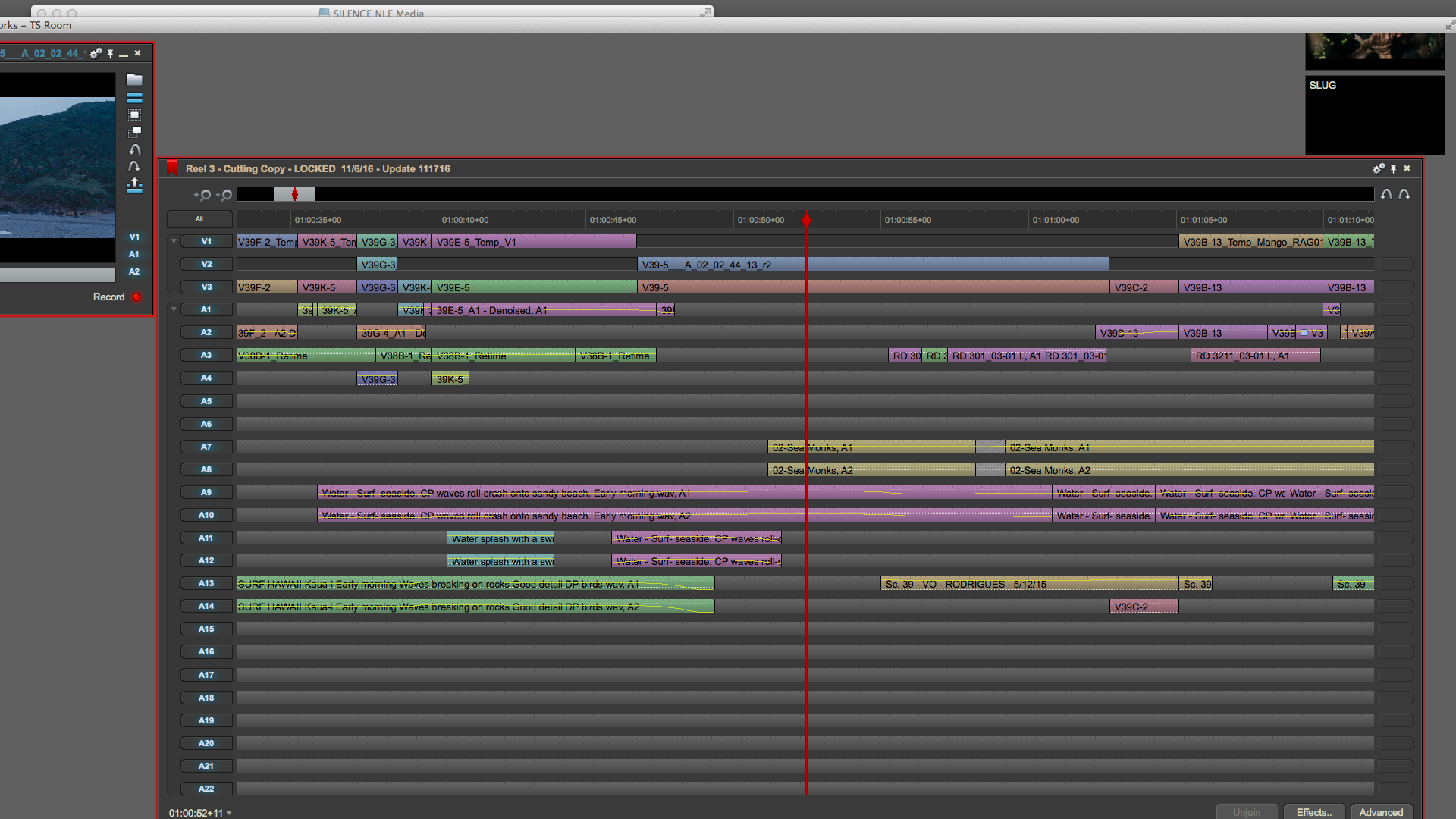

One of the things I like about Lightworks is that it has a controller like we used to have on flatbed editing machines, instead of a keyboard). The controller allows you to scrub along the sound very slowly, which you didn’t use to be able to do in Avid. I think you can now. And also Lightworks has a phenomenal sync reference system which means that if I’m cutting with 24 sound tracks I can do some experiments and throw myself out of sync during the experiments without worrying, because on the right side of the timeline Lightworks will tell me exactly how many frames out of sync I am on each of the 24 tracks. I can be three frames out of sync on track one and 24 frames out of sync on track fifteen and seven frames out of sync on track eight. When I’m done making the new edits I can then open up the relevant splices and click the mouse and it will pull all those tracks into sync again. Not having to worry about sync gives me great freedom.

One of the things I like about Lightworks is that it has a controller like we used to have on flatbed editing machines, instead of a keyboard). The controller allows you to scrub along the sound very slowly, which you didn’t use to be able to do in Avid. I think you can now. And also Lightworks has a phenomenal sync reference system which means that if I’m cutting with 24 sound tracks I can do some experiments and throw myself out of sync during the experiments without worrying, because on the right side of the timeline Lightworks will tell me exactly how many frames out of sync I am on each of the 24 tracks. I can be three frames out of sync on track one and 24 frames out of sync on track fifteen and seven frames out of sync on track eight. When I’m done making the new edits I can then open up the relevant splices and click the mouse and it will pull all those tracks into sync again. Not having to worry about sync gives me great freedom.

HULLFISH: Years ago I had a very similar controller for Avid. It’s a beautiful controller, right? Nice and heavy. I don’t own one anymore. Well, I think Avid can do a lot of those things and I’d love to show you but I know that you’re devoted to your LightWorks and a tool’s a tool.

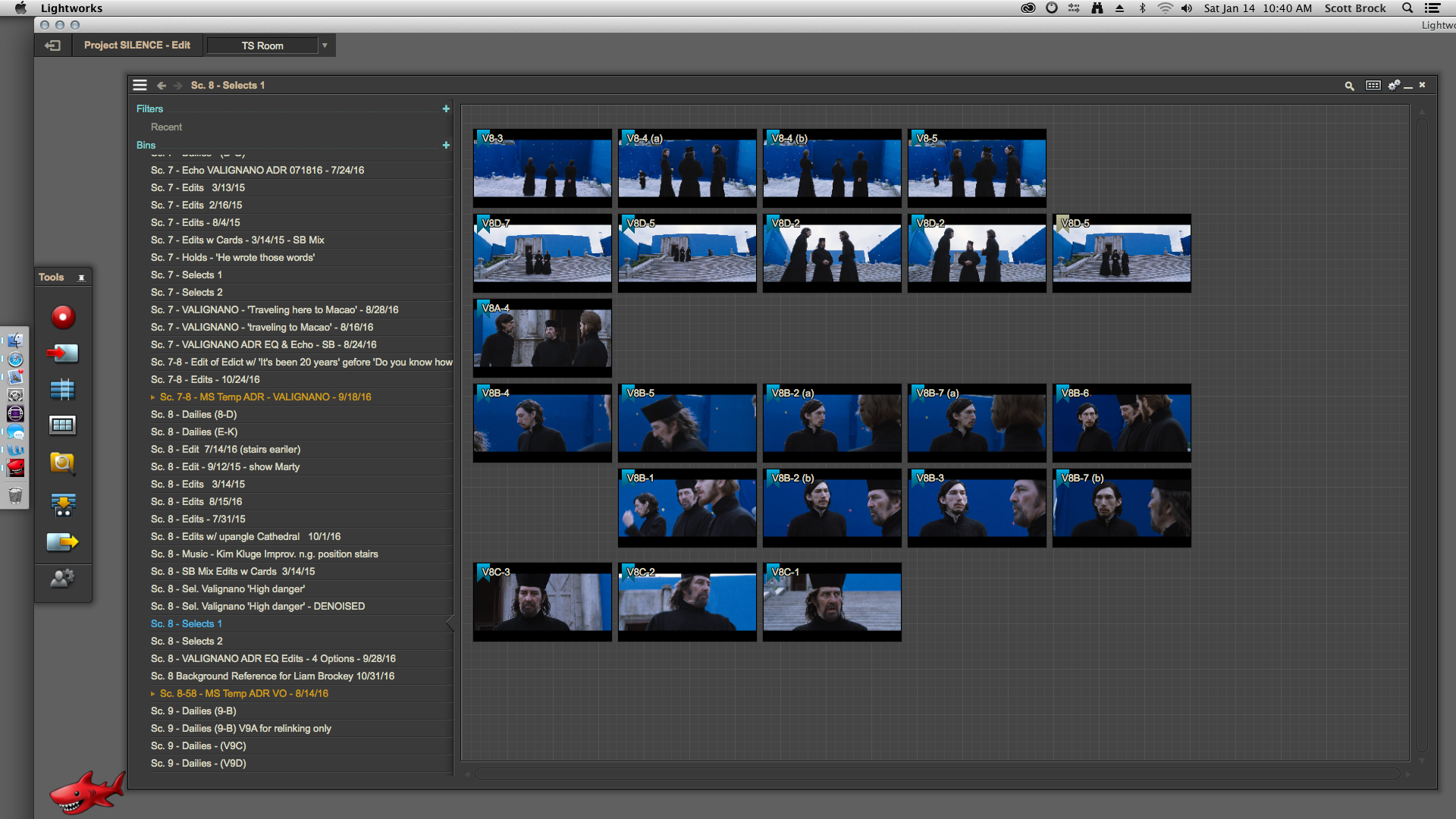

Schoonmaker’s associate editor, Scott Brock explains this screenshot from the LightWorks showing a scene from Silence: “Lightworks inverts Avid’s numbering of video layers, but they both play “top-down” the same way, meaning that a clip on the topmost layer will obscure any layers underneath it, unless you have a “blending” effect that is dual-track dependent (we never did that). V1 is the most recent and/or final VFX element, V2 will be our Sikelia-made VFX (not a final), and V3 is the original daily (work picture). About the audio tracks – A1-A4 are dialog tracks (including VO and ADR), A5-A8 are music tracks and the remainder are sound effects. This rule, however, gets broken all the time, especially when Mr. Scorsese and Thelma specifically require mono sound effects, which occurs frequently in the editing process. When building tracks “realtime” (translation: as quickly as you can!), strict discipline becomes, well… something of a secondary priority. Lightworks has a very spiffy little metadata feature which I use all the time: you can tag any sound-only clip as DIA, MX, or SFX. When it comes time for turnover to the sound department, you can then have the software create a duplicate of that edit with ONLY those clips which are dialog, another duplicate edit which is just MX, and another duplicate edit which is just SFX.”

HULLFISH: Some of the people that talked in this video mention that you had an emotional connection to the movie and I’m sure – as a film editor myself – that you would have an emotional connection to any movie that you edit. How is this movie different for you?

SCHOONMAKER: Well the subject matter of faith and doubt is so powerful and connected very strongly to me. I loved cutting the great performances of Andrew Garfield and Adam Driver, and I was so stunned by how convincing the Japanese actors who play villagers are in the beginning of Silence. Particularly the performances of Shinya Tsukamoto (who plays Mokichi) and Yoshi Oida (who plays Ichizo) were so deeply moving. These Japanese actors are not Christians – they’re Shinto or Buddhist – and yet they were able to play Hidden Christians with complete believability and they really got to me. Marty is able to put great emotion into his movies – it’s never cliched or saccharin or facile – and the scenes with the villagers just opened my heart and the whole movie has made me think deeply about faith. Mokichi and Ichizo are the heart of the movie I think. If you don’t feel their devotion and that of the other villagers, the rest of the movie doesn’t work. I just loved living with their characters. And then when you see them die for their faith – my God – it’s just devastating.

HULLFISH: You started to mention the faith-based aspect to this film. I’ve cut several faith-based movies myself and have been deeply moved by the content. And you said that the faith-based elements in movie affected you and will continue to affect you possibly the rest of your life. Would you mind sharing that or is that too personal?

SCHOONMAKER: It’s just opened up what was there inside of me, I think, but that I had sat on for many years. Scorsese and I talked a great deal about what it was like for us in the 1960’s among our fellow filmmakers at that time. It was okay if you were interested in something exotic – you know an Eastern religion or something – that was OK. But it was not cool to be Christian. I’d had a normal Protestant religious upbringing, but it hadn’t reached deeply into me. When I married Michael Powell (the British director of The Red Shoes, Black Narcissus, A Matter of Life and Death, Peeping Tom), and we were in England, he always wanted to go to church on Sunday in the beautiful Norman church in his little village of Avening, which is in the Cotswolds. I was a bit startled by this. He told me he just liked to be in “God’s house”. He also said it made him feel part of village life. I was quite struck by how insistent he was about this. He loved to belt out the hymns he knew by heart. Being in church with him began to open up my feelings about religion to a certain point. But Silence has really done it and it has done the same for a lot of people The experiences we’ve had, by the way, with the Jesuit advisers on the film have been quite extraordinary. Pope Francis is a Jesuit and we’ve heard that reading the book Silence is what made him want to become a priest. I’m not sure that’s 100 percent true, but all the Jesuits that I met during and after the shoot were amazing people. Their order seems to have incredible fervor. So the whole experience of editing Silence has just been marvelous and very unlike working on something like Wolf of Wall Street (laughs).

HULLFISH: Yeah that’s kind of the opposite (laughs).

SCHOONMAKER: Yeah it was highly enjoyable – wonderful. I loved working on it, but Silence is a life changing experience.

HULLFISH: Mr. Scorsese he almost went to seminary, right?

SCHOONMAKER: Well he thought he wanted to be a priest but then he realized he didn’t really have a calling. He loved being an altar boy. He loved the prayers and the mass. Old St. Patrick’s Cathedral was the neighborhood Catholic Church (not the big one on Fifth Avenue) and he was deeply influenced by a wonderful priest there, Father Principe, who guided Marty and his young friends by giving them books to read that opened up their minds. He gave Marty an important piece of advice which was that he didn’t have to stay in the neighborhood – that he should reach out beyond it. That was an enormous gift to Marty. He’s still in touch with this priest and celebrated his 50th year as a priest with him just last year. But when Marty left the neighborhood he had to really hide his interest in religion among friends. But you see it in all his movie – particularly in Mean Streets where the film opens with Harvey Keitel in a church. And then later there’s a scene where Harvey Keitel’s friends make fun of him because he believed something a priest told him and they mock him. That’s very seminal for Marty because I think he was sitting on and hiding his belief because it was not socially acceptable. He continued to go to church he stopped when a priest in another church told the parishioners that they should support the Vietnam War. And Marty found that unbearable. So he didn’t go back. He has his own very deep religious feelings but they’re not conventional He doesn’t go to church, but he thinks about religion a lot. He reads about it all the time. And it’s fascinating to talk with him about it, which we do all the time, particularly on this film.

HULLFISH: In the featurette, it said that everybody that worked on this movie knew that this was a special movie and it was a different type of movie for Mr. Scorsese. How is it different or special and how did that play out in the editing room?

SCHOONMAKER: Everyone on this movie cut their salaries to help Marty get it made. The budget was much lower than any of our other movies, so compromises had to be made all the time – but they never hurt the picture, because everyone was so excited about working on it that they made an extra effort to keep anything from looking “low budget”. We all noticed right away how excited Marty was on the set as he finally achieved his dream of making Silence. He always inspires his crews, but this time even more so. Some of the Taiwan crew had to be trained to rise up the level of a Scorsese movie, so that was an additional issue. The gorgeous locations Taiwan had to offer were very difficult to access. So the crew and Marty were always climbing up mountains or struggling to get to beaches and caves. They shot in typhoons and there was always mud and fog and rain. It could be freezing cold and terribly hot. So the shoot was very, very difficult. And the two main actors: Andrew Garfield and Adam Driver had to lose almost 50 pounds. So they were really suffering. But nobody complained which is quite remarkable because crews can complain a lot on locations. So everyone was just staggeringly devoted to this movie.

For example, Shsinya Tsukamoto (Mokichi) was almost being drowned by the waves when he was on the cross in the ocean. He had to deliver lines as he was being pummeled and not have the water go down into his lungs. And he refused to give up. He kept saying to Marty: “I’ll do it again… I’ll do it again.” And those wave machines that were in the tank we were using would not stop when Marty said “Cut.” It would take two or three more waves before Shinya could not have to worry about swallowing water. That was typical of everybody on this movie. And when they were shooting in the mountains, the fog would move in within 20 minutes. In the sequence where the Samurai come into the village for the first time because they’d been told there are priests there, Marty shot for a whole morning in bright sun, and then suddenly fog blanketed the entire location. So the crew said what do we do? And Marty said: “Shoot it. Have them emerge out of the fog. That will be great.” So they did and it’s one of the great shots in the movie. And then they had to go back and reshoot all of the coverage they had already done that day in the sun. So that’s the kind of thing that they were constantly facing. But Taiwan was so incredibly beautiful and everybody was just so inspired on this movie. It was remarkable.

HULLFISH: And this faith message has been affecting audiences as well.

SCHOONMAKER: Well, the film may not work this way for everybody. But for those who do go with it “mesmerized” is the word I keep hearing over and over again – mesmerized. That’s great. Some people leave the theater with these enormous questions in their heads and it provokes all kinds of very deep conversations for weeks afterward. it’s interesting that when some have told me how much they love this film they often follow that up with: “…and I’m not religious” or “I never cared about religion” or “I don’t normally think about religion.” But they are now! And I think that’s a real tribute to what Marty’s done. And he has presented both sides of the question – faith and doubt.

HULLFISH: Can a single edit reveal truth?

SCHOONMAKER: (Laughs deeply and mischievously). Occasionally, yes. I think so. I’ll have to think of a really good example.

HULLFISH: But I love the laugh. So that works for me.

SCHOONMAKER: (Laughs) Yes it certainly can. And I think we’ve had some moments like that. I just have to bring them to mind. I’m thinking of moments that have really been sort of profound.

HULLFISH: What was the goal of the music and what was the goal for the music NOT to be.

SCHOONMAKER: Marty has a great gift for putting music into a film. And I’ve seen from Raging Bull on how he creates scores himself with pre-recorded music he has known and loved all his life. For example Raging Bull, Goodfellas, and Casino were all scored by Marty. In Raging Bull some of the music is not up front – because it is coming through tenement windows just as Marty heard that music when he was growing up…Bing Crosby or Italian opera. But in Goodfellas, it is more upfront because in that film everyone had stereos and the music is very strong and always played very loud. On Casino, Marty had huge boards up in the editing room with the titles of all kinds of music that he thought he might want to use in certain scenes. And so we would try seven pieces of music against our first cut of a scene. And normally what would happen is one would just click. It would just be right or two would be and we would go back and forth deciding which to use. Marty’s fantastic at creating these scores. So when it came to Silence it was quite surprising to me that he said he didn’t want any music. “I just want the sounds of nature”, he said. He didn’t want the score to tell people what to think. But during the editing Kim Kluge, who is the conductor of the Alexandria orchestra in Virginia came to ask Marty to be part of a program featuring the music in Scorsese films, and it turns out he’s half Japanese and half Catholic, so he and Marty talked about Silence. And then Kim sent Marty a piece he had composed called “Meditations” and Marty sent it to me and he decided to put it into the film as an experiment. And that changed Marty’s mind because I think Kim Kluge understood what Marty was feeling about not wanting a classic score that tells people what to think. And Kim understood the novel very well, so he and his wife, Kathryn Kluge, provided almost 19 pieces that are almost unidentifiable as music because they emerge out of the sounds of cicadas or wind or waves. There were some other pieces given to us by Robbie Robertson and John Schafer from NPR, who has the wonderful New Sounds radio program. Those pieces were more upfront in the movie. but generally, Marty kept telling me to keep the music very low which is what we did. Many people say they get a strong sense of nature in the movie, which is great.

HULLFISH: So would you say that you didn’t actually temp with anything? You actually just used the music that ended up in the film.

SCHOONMAKER: We never use temp music. That’s really anathema to us. (laughs) I think it gives you the wrong idea for how to edit a film. For our first screenings, we either go with no music, or Marty will have already chosen some pieces. We would never use temp music. Never.

HULLFISH: That’s fascinating. Many editors I’ve talked to don’t want to cut with it necessarily or don’t even want to show something to a director with it. But eventually, when you show it to an audience there’s something in there.

SCHOONMAKER: Yeah I understand, but usually Marty’s either put something in or if we’re working with a composer they give us preliminary sketches of the score done on a synthesizer.

I wanted to talk about something that Marty does when the devout villagers are punished by the Samurai. The priests have to watch what happens to them hidden behind bushes in the hills. They can’t expose themselves and the villagers wouldn’t want them to expose themselves because they’re so thrilled to have priests again after many years without them. That would be the end of any chance of reviving Christianity in Japan if the two priests are killed immediately. The way Marty shot the point of view of the priests was remarkable. There’s a scene where Mokichi has died on the cross. It’s night and he’s hanging off the cross upside down. Guards need to carry him from the cross to a burial pyre, where his body will be burned so he cannot be given a Christian burial. His ashes will be thrown into the sea instead. Guards carry his body over very slippery rocks and it is an extraordinary shot. Marty did it all in a wide shot with a very slow pan – no tracking. There is no coverage at all. It’s so moving and it has many echoes of Christ being taken off the cross. I was stunned when I saw it and I said to Marty: “This is a masterpiece – and there’s no coverage!” I wasn’t saying that as a complaint. I was just amazed by his boldness in not shooting any coverage. And he said: “Yes, it’s about helplessness.” What he meant is that holding on the wide shot makes you feel how devastating it is for the priests in their hiding place not to be able to stop what is happening.

Their presence in the village has created this situation and now they can’t stop it. Of course, I was cutting to the priests watching in agony, but there was no coverage on the guards or Mokichi himself as his body is carried. Then later, when Rodriguez (Andrew Garfield) is captured. Marty is always shooting through the bars of his prison cage to the outside or from the outside to the face of Rodrigues with the bars in front of him – again emphasizing his helplessness. Even to the extent that he’ll do a pan of a body being dragged, past the cage through the bars and then swish pan back to a Samurai who then starts barking out orders. All done from within the cell through the bars. Always through the bars – because Rodrigues can’t stop what’s going on and it’s just driving him mad. Marty did shoot some footage of Rodrigues inside the cage not through the bars, but we only used it once.

HULLFISH: Can you tell me how you watch dailies? Do you watch them on the machine? Do you watch them in a theater? And also do you watch them in a specific order? You’d be amazed, with the interviews I’ve done, the different ways of watching dailies.

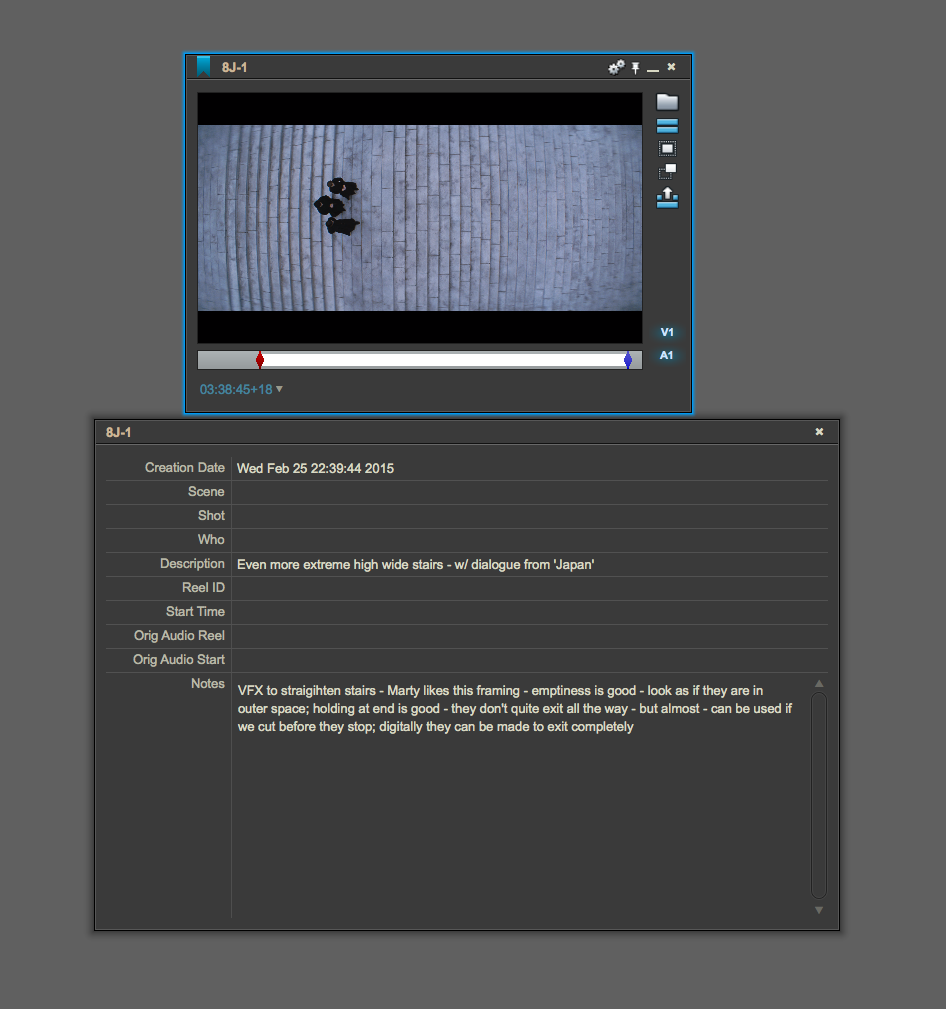

SCHOONMAKER: I always watch the dailies as soon as they come in on the Lightworks to make sure everything’s OK. Marty wants me to be an objective eye, so I hardly ever go to the set. Actually, I don’t have time to go to the set, even though I love to watch him and the actors work. But it’s not good for me to go because my eye will get prejudiced if I see how something is being shot. The crew will tell me they’ve laid 50 feet of track and the camera is going to boom up here and I don’t want to hear that. I want to see it in the dailies, and then if I think there’s anything I need to say to Marty about it, he wants me to do that. So I make very careful notes as I look at the dailies and then the most important time for me is when I look at dailies with Marty. Because he and I talk to each other constantly through the dailies. He tells me exactly what he feels about every shot… maybe he’s disappointed because he didn’t get what he needed, but in Take 7 he thinks he will have gotten it. And I tell him what I feel. And from that, I build very highly organized selects which indicate our preferences. So the first of my selects of a certain line reading would be the overall preferred and then the second preferred and so on, which takes some time, but is just invaluable because I never go back into the dailies. In LightWorks I can put our notes on the cards for each select – I can write extensive notes on the card for the tile, which is fantastic.

HULLFISH: That’s definitely something that Avid can’t really do. You can do it in what’s called Script View in Avid, but not just tiles, or thumbnails, or Frames, as Avid calls them.

SCHOONMAKER: That’s a real plus of LightWorks by the way which I didn’t mention which I should have. That’s really important to me. So looking at dailies with Marty is critical to our editing.

HULLFISH: And when are you watching dailies with him? In the evenings? After he’s done shooting? Or how are you guys getting time together?

SCHOONMAKER: It was very hard in Taiwan to do that because they were so exhausted when they got back from the mountains and the beaches. So we didn’t look at a lot of dailies. We looked at some. Enough for me to do some work but we mainly looked at them after we left Taiwan. It was just too overwhelming, particularly with the low budget crunch. But it was very important for me to be seeing the dailies all the time to make sure everything was OK. Particularly since we were shipping the film back to the States to be developed. So there was a delay there as well. When we shoot in New York City we try and watch at night or on the weekend.

HULLFISH: So you must have been way behind production, way behind camera if you are shooting film, shipping it back to the states, getting it developed.

SCHOONMAKER: They were transferring the film to digital immediately and we got that drive pretty quickly after the film got developed.

HULLFISH: Like a videotap feed?

SCHOONMAKER: Not a videotap. I mean the actual digital transfer.

HULLFISH: And then for the times when you weren’t able to sit to watch the dailies with Marty were you just going off of script notes or how were you making those selects that you were talking about.

SCHOONMAKER: I don’t make those selects until he screens. That’s very important.

HULLFISH: And that’s an interesting thing because watching something on set and watching something in a screening room are two very different things don’t you think?

SCHOONMAKER: Oh very! Oh very! It’s important to see the dailies large. We never screen on anything but a very large monitor, or in a screening room. That’s very important. Dailies sometimes don’t look like Marty has seen the shots on the monitor on the set. I mean the color and other things may have been changed when the cinematographer gives the timer at the lab some general notes of how he wants the footage to look. Marty was often pleasantly surprised when he looked at dailies. He would say “Oh my God that looks so great!”

HULLFISH: Tell me a little bit about your approach to a scene. How do you approach a scene when you first sit down? How do you find those first couple of important shots?

SCHOONMAKER: I work chronologically first and just put it together the way it’s supposed to go. I always put it together the way Marty wants it first and then if I feel an alternate route would be worth considering, the great thing about digital editing is that I can make three or four other cuts of the scene to show him when he comes in, which I could never have done on film. I loved film. But Marty would have had to wait while I took apart the film and hung it in the bin trying to remember exactly how I did cut it, and then recut it. And then if we didn’t like that go back to the way it was before. I got very used to having to do that. A great 80 or 90 years of film making were done that way. But I must say I experiment a lot more now with digital, a LOT more. You can just take the end of a scene and put it at the beginning just to see how it feels. And that would have been much more laborious on film. Plus we can ingest visual effects, we can have 24 soundtracks, we can speed things up, we can freeze frames, do split screens. We can do all kinds of things that we couldn’t do in a rough cut on film. Waiting for opticals back then could take two to five days. Now I can just do the “opticals” right in the editing machine.

HULLFISH: You were talking about the music and how important music is to Mr. Scorsese. Not the first project, but one of your first projects together was Woodstock right?

SCHOONMAKER: I worked on his first feature film Who’s That Knocking At My Door. We were a group of filmmakers who came out of NYU and we helping each other make films. It was a wonderful period, where there was a real ferment of creativity. And then Woodstock came along, right.

HULLFISH: One of the things that you’ve talked about in previous interviews and it’s evident in movies like Raging Bull is that Hollywood editors and I fall prey to this myself have a tendency to want to kind of make a slick edit. And sometimes you say there’s a reason to have an edit stand out and affect an audience and be rough.

SCHOONMAKER: Yes, there is. And there are quite a few of them in Silence. (laughs) Sometimes from necessity but also sometimes just to make a jolting sort of edit that is a bit shocking. But yes, we have never fussed too much about match cutting. And if you look at the great masterpieces in film history you will see continuity errors all over the place, because they had much less flexibility. Also, they probably couldn’t see that well on a Moviola. You know that little tiny screen – you probably couldn’t see some of the mismatches. But it didn’t matter. Now people are obsessed because of DVDS and Blu-Rays they can stop and freeze a frame and say “Oh, this doesn’t match.” We don’t care about that. We go for performance and emotion, what is working for a scene, and we feel very, very strongly about that.

HULLFISH: You talked about Who’s that Knocking at my Door and one of the things that I heard you say was the one while you edited that together Marty showed you how to build a scene between two actors and when to use the close-up. Can you verbalize maybe what that lesson might have been about when to use a close-up?

SCHOONMAKER: Well, Marty was teaching me editing. I knew nothing about editing when I started working with him. Nothing. He was training me from the very beginning. So he was teaching me about everything. He’s a great editor. It’s his favorite part of filmmaking and he has strong ideas about it, and one of the things that he doesn’t want to overuse is close ups. He feels that if you start doing that too early you can’t get a good enough build. And also sometimes you want to feel the environment of the room or location. He feels close-ups are too much like television sometimes. Doesn’t mean that we don’t use them to great advantage when the scene requires it. But he’s not someone who wants to do that right away. But it took me years to learn really how to edit. He taught me so much about how to build a scene dramatically. And also how to do the best by an actor’s performance. But it’s so complicated to discuss editing, isn’t it? I can’t verbalize it any more than that.

HULLFISH: I love truth in editing. Lots of us use over-cranked and under-cranked footage. And you use some over-cranked footage in Silence. How is that truthful? Something that’s so obviously not true to time, but it can be truthful, right?

SCHOONMAKER: Well, yes. And in Silence, you will see that when Andrew Garfield does finally step on an image of Jesus, which he has been resisting for the whole film, that was shot on the Phantom camera at 450 frames per second. And it’s such a critical moment in the movie. It’s very important to have it that speed.

HULLFISH: And how did that reveal the truth of the moment to you as an editor?

SCHOONMAKER: He falls down on the image of Christ in the shot, and I think the agony of what he’s going through is very, very beautifully shown through the slow motion. He has to give up what he thought was going to be his martyrdom, and learn to accept Jesus in a different way – he has to become more humble.

HULLFISH: Why does Mr. Scorsese focus on past film masterworks and why does knowing film history matter? I’ve seen you talk about how he watches films with you and with the crew and what’s the value of that to you?

SCHOONMAKER: Oh my goodness you don’t know?

HULLFISH: I certainly understand the value. I’m asking you to verbalize it to my readers, who also probably know the value, but some may not.

SCHOONMAKER: It’s like a great painting by Rembrandt. There are remarkable works of art from which one can learn enormously and that’s how Marty became a great director was by studying the films of the great masters that went before him. Studying them really carefully. At first, when we would go to see movies back when we were 20 or 25 we would only see the movie once, you know, there was no video. That first viewing would have to stick in our minds very vividly. Then video came in and DVDs and Blu-rays and now everybody can study films over and over again. But we couldn’t in the beginning when we were learning to be filmmakers. But it didn’t matter. What Marty saw taught him so much – like the great use of a camera, or great acting, or great set design, or a great, dramatic build in a movie. This is what showed him how to direct. And I wish every young person was doing what he did. It’s as if you’re a writer and you’ve never read other great writers or a painter and you’ve never gone to a museum and seen other great painters work? It’s unthinkable! But unfortunately, I understand from those who teach film courses that their students don’t want to look at, for example, black and white films. But 85 years of film history was black and white and there are masterpiece after masterpiece to see. It’s been one of the great joys of my life to be exposed to all of this by Marty and to have him excite me about the history of film. And of course then having married a great director, and both Marty and me being devoted to restoring the films he made with his great partner Emeric Pressburger, has been one of the great joys of my life. So, I just can’t imagine anyone becoming a filmmaker, or a painter, or a writer if they haven’t read great writers or gone to a museum and seen what artists have done before them. It’s unthinkable.

HULLFISH: And Marty’s got a huge collection of his own, correct? Of 35 millimeter prints of these great films.

SCHOONMAKER: Right. Plus about a hundred thousand DVDs.

HULLFISH: Were there any films that you watched in preparation for this movie?

SCHOONMAKER: Yes. One called Ugetsu which is a famous Japanese film by Kenji Mizoguchi, though only for certain scenes. There was a sequence on the water that Marty wanted us to see – not to mimic, but to be an inspiration for a certain mood. I think the crew saw a lot of Japanese films. I don’t come on a production until we start shooting, so I’m not there for those early screenings for the crew. But in the past Marty has asked me to look at films. Eisenstein’s Potemkin, for example, was an influence on Gangs of New York – the opening battle sequence. Very specific things he showed me that he wanted to be an influence on how we cut it.

HULLFISH: Great. Thank you so much for all of your time. I really appreciate it.

SCHOONMAKER: You’re very welcome.

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish

This interview was transcribed using Speedscriber.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now