Editor Christopher Tellefsen has a great body of work. Starting as an assistant editor on The Color of Money under Thelma Schoonmaker. His work as an editor started in 1980s starting with his first feature, Metropolitan, and includes early indies like Kids and Gummo, plus Capote, Analyze This (with director Harold Ramis, for which he received an Eddie nomination), The Village (with director M. Night Shyamalan), Moneyball (for which he was nominated for an Oscar), The People vs. Larry Flynt, Man on the Moon, Joy and Assassin’s Creed (for which I interviewed him earlier).

In this interview, we discuss the smart, emotionally-rich thriller, A Quiet Place.

(This interview was transcribed with SpeedScriber. Thanks to Martin Baker at Digital Heaven)

HULLFISH: When you took the job did you think this is going to be great, a movie where basically the whole thing is silent? What drew you to it?

TELLEFSEN: The concept was what drew me to it absolutely! Because the challenge of it, the idea of being able to make a movie with practically no dialogue was so intriguing. We actually had one cut where there was only one scene with talking in the basement, but that was a little too much. That was a step too far.

HULLFISH: I’m not a horror movie fan so…

TELLEFSEN: Me neither, but I was very intrigued by the storytelling involved and I thought it was fascinating the way it was thought out and the way it was structured.

HULLFISH: The fact that you’re not a horror movie fan…

TELLEFSEN: I wasn’t a baseball fan, yet I edited Moneyball. I learned a lot about baseball.

HULLFISH: My question about that is, does it become difficult to cut?

TELLEFSEN: The thing about it, that also drew me to it, was that it was a very well structured family drama.

The whole underpinnings, the tension between the father and daughter was very strong and very interesting and beautifully played. Millie is brilliant. She’s such an interesting and inscrutable performer. She’s just somebody that exudes so much with so little. She’s very, very skilled.

HULLFISH: You mentioned the structure of the film. There are some big leaps in time.

TELLEFSEN: Well, there’s an initial huge leap in time. We start at day 89 and then we go to day 272, I think it is, or something like that. Then it’s two days. Right after that it’s just 48 hours and that’s really interesting. I like that aspect of it as well, that you could plant this story and get everything immediately and then go a year later and then you start to pick out details: She’s pregnant. Wow! You know, that’s not the best idea in a world where you have to be quiet. You get that there’s still tension with these characters feeling guilty, and the young boy is still very fearful and there’s his narrative arc of becoming braver, and the beauty of Millie figuring out the power that she has in her cochlear implant. In a way it’s actually quite simple, yet there’s so much detail that goes into making it believable. That’s that’s the big aspect of the writing and of the presentation.

HULLFISH: Was the structure as scripted?

TELLEFSEN: That structure is absolutely scripted. In terms of that, there was an incident that happened and then we’re approximately a year later.

HULLFISH: And I love the fact that the audience was really given great opportunity to figure things out on their own.

TELLEFSEN: Yes. John had a really good sense of the storytelling and it goes very deep in terms of preparation too. The set is amazing. That set was something that he found in upstate New York by Google Maps just like a good size farm with a house and a barn. They built the silo and the production designer Jeffery Beecroft, who did a fantastic job — also planted acres of corn.

HULLFISH: So Krasinski wrote this as well?

TELLEFSEN: The original writers Brian Woods and Scott Beck wrote the original script which was picked up by the producers of the film. John was working with them on a Jack Ryan series that’s going to be coming out soon. So they went to him asking him to play the father and he read it and was so taken with it that he said, “I’ll do it if I can be a part of rewriting it and directing it” Then Emily insisted on playing the role of the wife. That wasn’t the plan, but when she read it, she said she just had to do it.

HULLFISH: I’ve worked with a director who was also in the film itself and it’s very odd to deal with issues of their performance. You are discussing the qualities of takes or opinions of their believability.

TELLEFSEN: We were very aligned in terms of what we felt played best, so we had a good understanding of what the strongest performances were. We didn’t have any particular disputes about performance. It seemed a lot of it felt very clear.

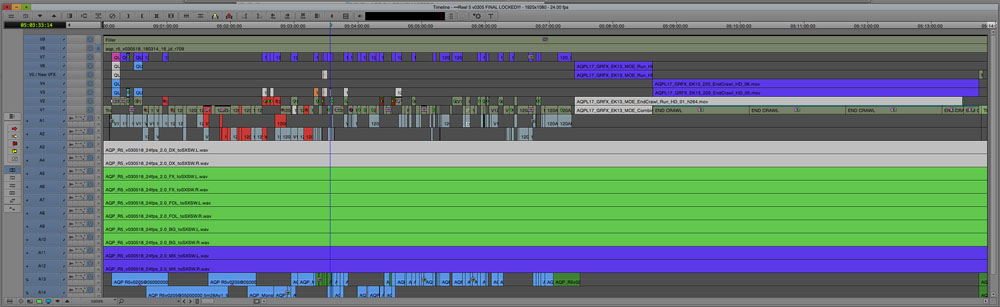

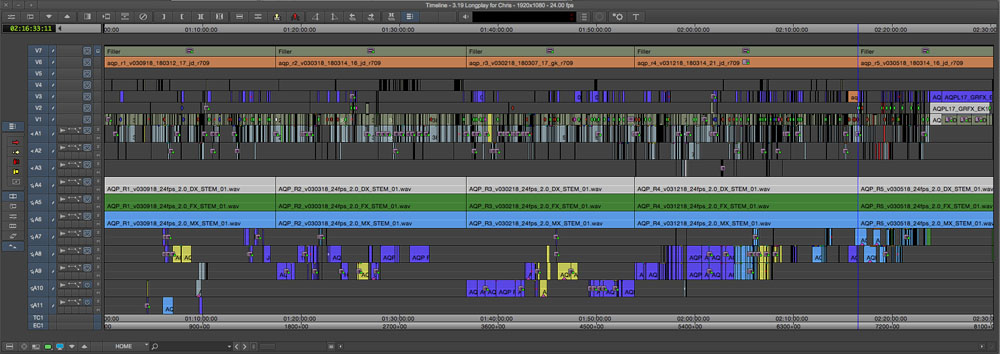

You know, we started shooting in September and we were locked in March. And ILM created the creature in that time. They didn’t even lock down the concept until January.

HULLFISH: Tell me a little bit about the sound design. How much of that did you feel like you needed to fill in as you were going before the sound designers came in?

TELLEFSEN: The key moments were particular. We understood where these key moments were. They needed to be expressed through sound design, but they were very much understood. E Squared is the name of the company. (e2sound.com) Erik Aadahl and Ethan Van der Ryn really did a wonderful job. The creature’s sound has this kind of clicking kind of communicating thing. They really got that, and it has a wonderful uniqueness. It doesn’t sound like any others. And the whole thing of dampening the sound when we’re with Millicent to be inside her head as much as possible. That was always the intention but they really brought it to life.

HULLFISH: Sound design sometimes affects your sense of visual pacing and rhythm. Do you think that’s true?

TELLEFSEN: Oh, definitely. I can’t say that there were things that we recut because of sound design. No. But there was a real exchange between visual and sound, very much so.

HULLFISH: Did you have to imagine some of that stuff? Would you actually try to cut sound in?

TELLEFSEN: Or silence. There was a lot of dropping to nothing. Then the nothing became these muted, interesting tonal things. My early edits just cut to dead silence. But there is a moment of dead silence in the final film when she’s in the basement and makes the decision to turn it on. It goes to dead, dead silence before she uses it as a conscious weapon. It’s very effective.

TELLEFSEN: Or silence. There was a lot of dropping to nothing. Then the nothing became these muted, interesting tonal things. My early edits just cut to dead silence. But there is a moment of dead silence in the final film when she’s in the basement and makes the decision to turn it on. It goes to dead, dead silence before she uses it as a conscious weapon. It’s very effective.

HULLFISH: Did you find with some of the audio transitions, did you feel like you needed to cut something in there whether it’s a creature screaming across or a gunshot or some noise?

TELLEFSEN: That depended on the situation. Everything was very specific. The transitions didn’t change drastically. It’s more expanded or contracted certain areas. They surprised us with some lovely things too, subtle details. The sound team was careful not to overstate. So many films of this genre go overboard with sound design. The mix was great. We had to work very fast to get a cut out for SXSW by March 9th.

HULLFISH: What about music?

TELLEFSEN: Music. Marco (composer, Marco Beltrami) hit on the family theme and the dramatic music pretty early on. Our intention was to not overuse music, to keep it a bit held back. We had him do some composing not even to picture, and he hit it hard with the monster suite, which is that heavy, Interesting piece that plays when the shit really hits the fan. It goes very deep and low and rhythmic — slowly rhythmic and that was great.

HULLFISH: Were you temping with anything?

TELLEFSEN: We temped with a ton of things. Very sadly with that wonderful composer who died recently.

HULLFISH: Jóhann Jóhannsson.

TELLEFSEN: Johann Johannsson: Prisoners. Sicario. Those were the key ones that we utilized.

HULLFISH: One of the things that I was struck by, was there’s always the decision when you’re having a conversation playing something on or off of the person who’s speaking or on the reaction? And yet this entire film was American Sign Language. So how do you play something off when you have to see the hands?

TELLEFSEN: Interesting question! We didn’t put the subtitles in until way later. We played it very much just like communication. And you just feel communication whether it’s language or whether it’s sign language, it’s two people responding to one another and having a conversation.

HULLFISH: I knew there had been subtitles, but I honestly couldn’t remember them.

TELLEFSEN: We edited without subtitles until we had to show it to people, and it was a tough film to show to people because we didn’t have the creature till the very last minute. Some of it was mocap and John played the creature in the basement, which could be very distracting to see him walking around like this. (Mimics John portraying the alien creature) You can’t show that.

HULLFISH: You can understand almost all of the sign language through context and reactions.

TELLEFSEN: And we didn’t always use the subtitles when it felt like it was just understood.

HULLFISH: Do you remember how you handled having to show ASL and do reaction shots?

TELLEFSEN: It wasn’t difficult. You get the rhythm of communication whether it’s oral or signed because it’s all expressed in the face and the eyes and the rhythm of the hands and it had to be very right too. One thing that I thought was very interesting was that Millie’s sign language was her natural language and everyone else felt like it was their second language which is very fascinating.

HULLFISH: I love the idea that the sign language felt different for Millie than it did for the other hearing people in her family.

TELLEFSEN: Millie’s had a fluidity and the other people signed a little more precisely, like how someone who learns a language speaks compared with someone who is fluent and born in the language.

HULLFISH: It’s like an accent.

TELLEFSEN: That just adds to the authenticity.

HULLFISH: Let’s talk about what drew you to this project.

TELLEFSEN: What drew me to it honestly is the lack of dialogue. To make a movie and to tell a story with that little amount of dialogue is a fun job. It was very well executed and it became something that was very doable. It’s a great story that you believe and you care about. That’s the most clear and important thing: these are very full characters that we really care about, and when they’re in danger, you feel it. You care about it.

HULLFISH: That’s always the big dance of how much character development can you do versus how fast can you move the story along.

TELLEFSEN: True. That really is such a key element because sometimes these things that aren’t necessarily developmental to the story, but they’re details that add so much. Like, it’s so wonderful to see the kids playing Monopoly with these little pieces of felt and soft things. Another thing that’s very thought out and constructed is, the father is all about survival, and the mother is about living, about making it a living place and human and having a life and not just surviving.

HULLFISH: How do you create subtext with so little dialogue, or “text” to begin with?

TELLEFSEN: One of the big subtexts to this film is in terms of gender roles. The boy is fearful yet he is drawn out. And the girl is brave and wants to go out, but she’s held back. And she’s raging over it too.

HULLFISH: What is your approach when you are opening up a fresh bin with a bunch of dailies and a blank timeline?

TELLEFSEN: I vet the dailies very carefully. I watch them very carefully and look for details and nuances and look at them structurally and aesthetically. Like what feels like an opening shot? And also coverage wise: how much coverage there is. What is the most interesting combination. Sometimes I’ll have scenes shot varying ways and then it’ll be like, “I don’t want this to feel like confetti.” I want it to feel deliberate. So it’s finding that deliberate way of really feeling you’re in the right place at the right time. And then, when there IS dialogue, how and when to be on who. It’s all about emphasis. Where to find that emphasis and that rhythm, and also what I find, is that I’ll do a first cut of a scene and try not to have the scene feel like it has a beginning, a middle and an end, because you want them to flow into one another. So it’s a matter of finding that shape and rhythm and openness to bring you into the next thought.

HULLFISH: When you get that first cut done, do you find that you have to revisit the dailies?

HULLFISH: When you get that first cut done, do you find that you have to revisit the dailies?

TELLEFSEN: Oh yeah! I revisit dailies until the end.

HULLFISH: And how does your assistant set up your bins? Are you using selects reels or are you just going straight to clips?

TELLEFSEN: Straight everything, to look at all the clips. I then make my selects and work from there.

HULLFISH: Otherwise you’ve got 90 minutes of material for a scene.

TELLEFSEN: I make my own selections.

HULLFISH: Because that helps you understand the material better?

TELLEFSEN: Yes. I look for the shape of the scene and for the moments that really stand out. And also, I try very much, if I’m able to, I try to see dailies on a big screen. There’s not always that luxury, but I miss, back in the old days of film, we would have formal dailies and it was great. You really felt what was cinematic.

HULLFISH: All right. Where do you stand on the great debate of how early you start assembling individual scenes into either reels or little sequences?

TELLEFSEN: I do it as soon as I have two scenes that are consecutive. That’s the way I work, and I know everybody works differently. I like to get a sense of the connectivity of things because context is everything. A scene doesn’t mean anything until it’s reacting to something down next to it.

HULLFISH: When you edit that first pass at a scene, do you edit it very quickly?

TELLEFSEN: It depends on the scene. The amount of time I spend on a scene when I first cut it completely depends essentially on how difficult the scene is. How much I have to choose from and how much I have to work around. Or if there is a problematic performance. Sometimes I’ll have a scene that let’s say the director’s not happy about. I just try to be as honest as possible and try to really assess it in the context of the whole film and be very clear and use my own experience to advise if something needs reshooting.

HULLFISH: Were there reshoots? Did you feel like you knew that there needed to be reshoots?

TELLEFSEN: (SPOILER ALERT) The way the climactic scene where he sacrifices himself was originally shot, it was very rushed. It was over a group of days that were kind of disconnected. And it wasn’t shot in a way that connected him to the kids. Within the first cut we were very clear about the fact that it was not playing as strongly as the rest of the movie. It was a point in the film that had to really sing.

HULLFISH: Was the whole scene reshot, or did you have to deal with mixing the previous shoot with a reshoot?

TELLEFSEN: I would say 60 percent. All of the kids in the car hiding and then the creature crawling over the truck was not reshot. What was reshot was them coming together after the silo scene where they embrace We needed a great moment for them to be together before what follows. When they go to the truck is all from the first shoot, then him getting mauled by the creature, and then standing up and screaming was reshot. John really knew what to do then.

HULLFISH: Did you edit in LA or New York?

TELLEFSEN: In New York. I’m a New Yorker. It was also for the New York tax break.

HULLFISH: Youre the third interview I’ve done with an editor who cut in New York for that tax break. Also Tatiana Riegel, for I, Tonya and Tom Cross for Hostiles.

TELLEFSEN: By the way, another thing that we shot was a beat after Emily Blunt’s character says, “You have to find them. You have to protect them.” We shot the scene of him going into the basement and looking for them on the monitors. That was shot later. Also the first scene of him in the basement where he’s doing the Morse code. In the original script and shoot a lot more happened during the scene later in the film where Emily comes to him and they dance. It just seemed to make sense to put the emphasis early on him doing the Morse code and understanding more about what had happened in the past: the alien invasion.

HULLFISH: We were talking earlier about pacing the overall film — to take time to build character. That the connection is great between these characters when Emily comes down to the basement just to be with him.

TELLEFSEN: Yeah. You have to feel that this is a loving relationship. This is real. On top of all that they’re going through that they are able to at least have a moment together says a lot.

HULLFISH: The movie takes off immediately basically, so it’s not like one of those films where you’re trying to get to the point where the protagonist and the antagonist finally meet.

TELLEFSEN: The thing is, having that really strong incident right up front, plus getting a lot of time inside the pharmacy to understand things. The beauty of it is, each detail is meant to create a lean forward moment. You’re intrigued and you want more. The teasing out of those things, and then getting hit with what happens before the title card, gives it the jolt that it needs. And then you can slow down for a while and take some time to build character. You have the human moments and then the spikes come in very specific places. The thing that the studio was salivating over was that it was a genre film with a human story that you connect with. This is gold. Marketing was so on this from the first day, that it drove my assistants crazy. They were constantly getting requests from marketing.

HULLFISH: One of the things you mentioned which I love talking about, is not just the individual pacing of individual scenes, but the pacing of the whole movie.

TELLEFSEN: (SPOILER ALERT) If you see the movie, once Emily’s character comes downstairs to the basement in her bare feet, and steps on the nail, it’s non stop from there. That’s a hard kick, and it’s relentless from there until the one dialogue scene, which is the only time it slows down.

HULLFISH: Are there any tricks to building that tension?

TELLEFSEN: It’s how you tease it and feel it. You get the right rhythm going, so that you get a little bit of a misdirect. You want to not feel like, “Oh, it’s coming, it’s coming.” You want to move it, in little ways, towards and away from that.

HULLFISH: Can you talk to me about things you remember about cutting any of these scenes? Decision making, shot choice, or challenges or approach? Maybe how the purpose of the scene was demonstrated in the cutting of the scene? These scenes are not really the way you cut them in the film. The marketing department has shortened them and chopped them up.

TELLEFSEN: These clips are totally butchered and do not represent the final scenes.

I will talk about these three scenes as they live in the film.

The Bathtub:

This scene is fed by the scenes that proceed it. Emily was so strong and believable as a pregnant woman going into labor and having to stifle her need to scream. You could sit on her performance for an hour and be fascinated. It was finding the right rhythm of her suffering. It had to be excruciating, yet not too much. Then the measurement of the parallels, of her son setting off the fireworks to distract the creatures, and her husband loading the gun as the creature came nearer. This is a pretty classic danger/suspense trope.

The Bridge:

Again this scene is fed by all that came before. The time taken in the pharmacy provides the understanding that making too loud a sound is dangerous, that Millie’s character is deaf, the restlessness of the young boy and that the toy and batteries are a time bomb. This is all teased out and measured to build suspense. The quiet and the misdirect of the music taking a more lyrical turn as they walk barefoot feed the surprise of the coming incident.

HULLFISH: Chris, thank you so much for sharing with us. I really appreciate your generosity.

TELLEFSEN: Thank you, always a pleasure to share with you and your readers.

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish

The first 50 interviews in the series provided the material for the book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV Editors.” This is a unique book that breaks down interviews with many of the world’s best editors and organizes it into a virtual roundtable discussion centering on the topics editors care about. It is a powerful tool for experienced and aspiring editors alike. Cinemontage, CinemaEditor magazine and FirstFrame, the magazine for the Guild of British Film and TV editors, all gave it rave reviews. No other book provides the breadth of opinion and experience. Combined, the editors featured in the book have edited for over 1,000 years on many of the most iconic, critically acclaimed and biggest box office hits in the history of cinema.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now