Jeffrey Ford, ACE has been working in the Marvel Universe for several years. His previous projects include: Doctor Strange (additional editor), Captain America: Civil War (editor, for which I interviewed him previously), Avengers: Age of Ultron (editor and associate producer), Captain America: The Winter Soldier (editor), Iron Man 3 (editor), The Avengers (editor), and Captain America: The First Avenger (editor). Ford’s other work includes films like Public Enemies and One Hour Photo.

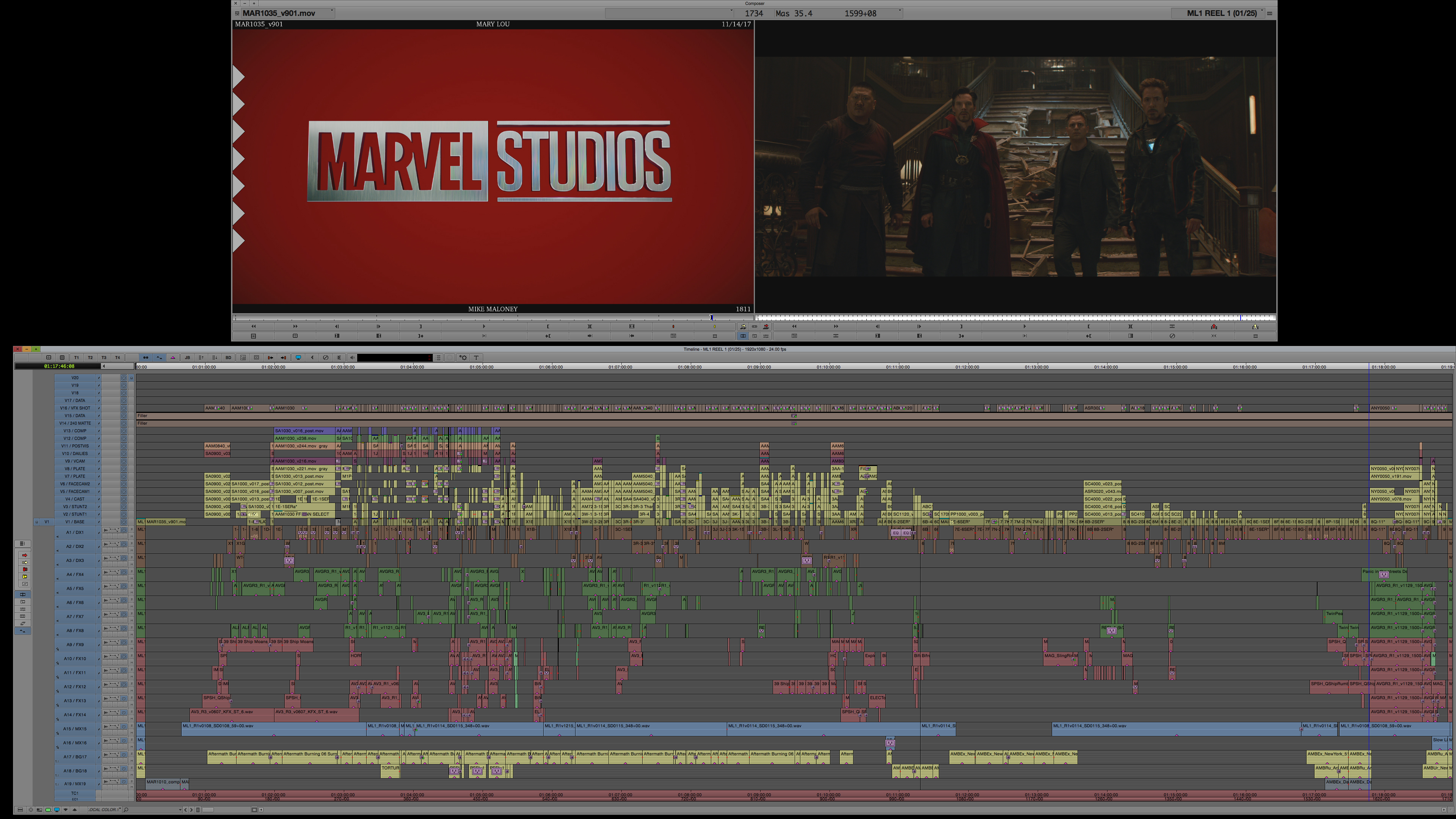

This interview is about his work on the latest installment in the Marvel universe, Avengers: Infinity War. (We have screenshots of timelines and other imagery that we’re trying to get approved by Marvel. Check back in later to see those if they’re approved. Also, this interview is spoiler-free!)

(This interview was transcribed with SpeedScriber. Thanks to Martin Baker at Digital Heaven)

HULLFISH: Do you feel it’s possible to get typecast as an editor.

FORD: I’m feeling like I have been lately. It’s like I’m the Marvel editor but one of the nice things about it is there’s a group of us now, regulars who have repeated on other Marvel films. I have colleagues like Craig Wood, Dan Lebental, Wyatt Smith, Debbie Berman, Fred Raskin. These are all really cool editors who have worked on multiple Marvel movies, so there’s a club forming of editors who have had the good fortune of doing more than one at the studio.

HULLFISH: Do you have a favorite movie that you’ve edited?

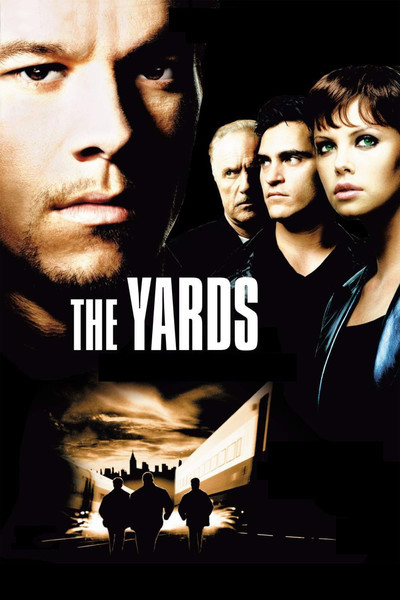

FORD: The first film that I did as a solo editor, which was a movie called The Yards for James Gray has a special place in my heart. It was always really important to me not just because it was my first editing credit but it was also a spectacular piece of work by one of the best directors of my generation. It was nominated for a Palme d’Or at Cannes. That will always be a really special time for me and a really important film.

FORD: The first film that I did as a solo editor, which was a movie called The Yards for James Gray has a special place in my heart. It was always really important to me not just because it was my first editing credit but it was also a spectacular piece of work by one of the best directors of my generation. It was nominated for a Palme d’Or at Cannes. That will always be a really special time for me and a really important film.

HULLFISH: Talk to me about your career progression up from assistant through a series of films with great directors.

FORD: Success in my forward progression as an editor in my career has been due to being in the right place at the right time. It looks like I had a lot of lucky breaks but in some of those cases it was just being available at the right time for the right project.

I started out — out of film school — as a camera assistant for a while working on set. Being a loader and a focus puller and I really liked being on set, but I was always really passionate about editing. When James Gray made his debut feature, I was able to get hired on. He was a friend of mine and he was able to bring me on as an apprentice editor and I started my editing career on that movie. It was all about proving myself on that film and then finding a way to continue to work as an assistant. I was fortunate enough to then get on a crew with Richard Marks. He’s a great editor — one of the best and I worked with him on several pictures. I learned a lot from him about everything that goes into being a great editor.

I learned cutting room protocol and got a greater understanding of the political aspects of working in the cutting room. I got to work with some incredible directors like Richard Donner and James L. Brooks, so I think working for James Gray and working for Richie Marks, those two people were instrumental in informing my understanding of how to be a filmmaker and editor and it was thanks to my assistant work with Richie that I was able to get my first editing gig with James on “The Yards.” I needed a reference to edit James’s films because I had no previous credits. Jim Brooks vouched for me. Getting on to that picture at Miramax was was a big step forward and I needed the support of James I needed the support of Richie and I needed a reference from Jim. All that was necessary to get my foot in the door and get me started cutting. And then once I started cutting it one thing sort of led to another. James Gray introduced me to Mark Romanek who then hired me on One Hour Photo. That was another incredible experience and it transformed my style.

HULLFISH: Talk to me a little bit about that. You said that working on that film changed your style.

FORD: Romanek is a very exacting director. He has incredible precision with his ideas and his approach. So I really had to step up my game in terms of being somebody who could conform to the stylistics of a director. And it was a valuable lesson. I’m not around to edit a movie to make it feel like a Jeffrey Ford movie. I’m around to make it feel like the director’s movie. I learned on that film — and sort of intuitively over the course of my career — that our job as editors is to really try to bring the director’s work to screen and find the editorial style that works for that movie and that author. So you have to take your stylistic cues from the material and from the author so that you’re creating something that has a rhythm and a tone that has a connection to what the director’s trying to say or what the director’s approach is to the material. It’s important that the tone of the movie and the style of the movie and the rhythms of the movie fit that subject matter. Because when you try to impose a style that doesn’t work, you really can push the material in another direction and that can confuse the audience and make the movie really not work. Very often you see movies where the stylistics are at odds with the material.

HULLFISH: Let’s discuss the balance of character development and action. Especially in a film like a superhero movie where it would seem very easy to lose one for the other.

FORD: Without giving too much away, Infinity War does not prioritize action over character development. It’s a very character driven movie. And it’s also a very actor-driven movie. And I would say that the thing I’m most proud of on my work on Infinity War is the shaping of the performances. And I think at the end of the day superhero movies are fun and entertaining and exciting, but they succeed or fail almost exclusively on the quality of the characters and the story because no matter how great the visual effects are, the best visuals can’t save you if you don’t have characters and a story that is satisfying for the audience, one that they’re connected with and can relate to. So I think balancing character and action to me is not really ever a consideration because there really isn’t a balance when you think about it — at least in the films that we make a Marvel — because the characters drive everything, so action is character and the action moments have to reveal character or story. They can’t be separate from that.

There is always a tendency on these films to try to want to string together some great moments in an attempt at fan service and to be fair we occasionally do moments in the films where there are little winks and nods to fan-service moments. The fans know so much about these characters that sometimes you can just do something very subtle and the audience will laugh knowingly because they know so much about them. But when we’re putting these films together, what we’re looking for is not so much a balance between character and action but it’s a flow and a dynamic quality to the narrative so that there are moments of intense quiet and moments of intense loudness and you’re basically interleaving the big loud colorful vibrant moments with moments that are more subdued, subtle, and understated. All of that is in service of the rhythm of the story. When I say that I don’t just mean color and sound from a visual standpoint but I mean that from an emotional standpoint too. You want a balance of scenes that are intensely emotional and sometimes very sad and some scenes that are also filled with joy and the elation of superhero action and the moments that make you stand up and cheer. And I think modulating that is the key to getting these films to work in a way that makes them feel like we’re rolling along and you just feel like you’re being carried along on a wave of narrative dynamics.

HULLFISH: I love that point of importance of regulating the dynamics of the movie. I think of it as a musical thing right? Great music has dynamics. They intersperse loud and soft and fast and slow.

FORD: Yes. Any great work of drama onstage has this as well. Everything can’t be at force ten and sometimes you see action films where there’s no scenes they’re just a collection of little vignettes that lead to the next set piece. And they become loud and oppressive and they push the audience away and I don’t connect with those films.

HULLFISH: With a film like this, I would assume that there was a lot of previz. How did you interact or work with the editors of the previz, or did you cut the previz yourself?

FORD: There was a lot of previsualization on this film. Gerardo Ramirez who works for The Third Floor, he was our lead and worked on the film for quite a while. I think he was on the movie for about a year during pre-production. And that continued into production as we came up with needs and ideas for things that we needed to change and alter. And then he also did augmentation to the shots after we shoot them — which we call post visualization — where you apply digital elements to the photographed elements already shot. So he is a huge resource. He had a great team of artists who helped him. He doesn’t work alone of course but he is a conceptual guy who comes up with shots and ideas for sequences. They will cut those together sometimes. Other times he’ll send me the raw material and I’ll cut them together but we worked very closely together over the course of the process. We feed on each other’s ideas — bounce stuff off the visual effects supervisor and the directors and work as a team so we’re all sort of running at the same goal. And I think that that’s the important part of a successful previz relationship is that you’re all working in service of a screenplay because randomized previsualization of gags or ideas or moments doesn’t get you anywhere.

The movie is a story and it’s told with characters and pictures and that has to be served by everybody. Previz is a great thing for movies like Infinity War where there’s a lot of digital characters. There’s a lot of digital environments. There’s no way you can evaluate or understand how to shoot a scene until you’ve previsualized it because we haven’t built the set. So understanding how to compose for a set that doesn’t exist, it’s only possible if you have some kind of conceptual material visually ahead of time and Third Floor did an amazing job. We are constantly altering the shots. I mean pretty much every day from the beginning of production until just weeks before the release — we’re still creating imagery for the movie as we’re changing the film. There’s a lot of shot design and shot invention that goes on during the post-production process on a Marvel movie — on every Marvel movie — but I think there may have been more on Infinity War than in the past because so much of the sets were virtual and so many of the characters were virtual.

HULLFISH: When you’re working on these larger set pieces I would think that for those things that are largely digital, you’re relying mostly on those previz sequences. So much of what you’re trying to edit hasn’t been created yet fully while you’re trying to tell the story. What are you doing to get a sense of some of those scenes?

FORD: For an action sequence we usually have either a previz sequence or series of storyboards that are prepared ahead of time before we photograph and we cut those together and shape them into a sequence that exists so that the cut of the movie is always evolving and there’s always a version of every scene in the cut even if it’s just a series of storyboards or sketches and that will be in my timeline as a stand-in for what that scene will be once it’s photographed. And usually, those storyboards are what the crew is looking at as they photograph the scenes so they provide a guide to everyone. And then once the material gets photographed and starts coming in, I’ll cut the plates together as best I can, cut the performances together the way I want it. If it’s an action scene, if it’s based on a stunt person’s performance or an actor’s performance, obviously I’ll cut that material and send it to the postviz team and they’ll add background’s or whatever they need to add to it. Occasionally I work directly with the previz because the shots are 100 percent CG. So in those cases I’m working with The Third Floor team to dial in the shots and make them function in the sequence. The film is previsualized for pretty much everything except dialogue scenes. Sometimes before a frame of film has been shot, we’ve already really laid out most of the movie.

Of course, there are constant changes and then for dialogue scenes those are usually based on actor’s performances. I cut those the way I would cut any other scene in any other movie whether they had visual effects or not. In the case of Infinity War, we had the gift of Josh Brolin who gave truly one of the great performances I’ve had the privilege of cutting in a Marvel movie. He is absolutely breathtaking in his performance. It is the thing that people are going to take away from Infinity War as one of their favorite things. He is amazing and cutting that — watching him work and spending time with him on set — it’s fascinating to watch how sophisticated and deep he went with this character. And so my job — once I got to the cutting room — was, even though he was going to be replaced with a digital copy, or a digital extension of what he did, we wanted to carry his performance through as nuanced as possible all the way to the end.

HULLFISH: And so for those scenes even though I guess they were mocap you were cutting with his performance on camera.

FORD: 100 percent of the time. What we did was — when Josh had a scene with another actor — Josh would be on set and he would be in a mocap suit with a face camera and he would have an extender on his head to account for the higher eye-line that Thanos would have. would have and they shot the scenes on the sets, so the actors who were with him in the scene were also on the set with him and the set was lit and he was using the set for the plates of the non-CG actors. So it was like shooting any other scene.

It allowed the actors who were in the scene with Josh to emote and relate to him in real time as he was acting, and we could actually capture his motion capture data as he was acting so we didn’t have to go back into a motion capture studio and reproduce what he did. We could carry what he did in the moment with his other cast members into the final edit and I could edit with that material. It was hugely valuable and I think it’s one of the things that made the movie special because we really do have a Josh Brolin performance at the center of this character. There wasn’t a lot in between what he did and what Dan DeLeu — who’s our brilliant visual effects supervisor — did to bring him to life. Obviously, Dan had to do incredible work to create the character and light him but the eyes and the muscle movements and all the things that Brolin brought to the nuance of that character were there.

HULLFISH: Were you able to do what would essentially be a jump cut in the middle of a scene because you knew it would be mocap so you could say, “Oh I’ll take this part of this performance and then without even going to a different camera angle I will just cut to a different part of a different take?”

FORD: You can splice together the mocap performances sometimes, but it’s not always possible. What I learned from doing this intensive mocap picture was that the closer you get to a one to one the better the results are. And it’s the nuance of the actor that can’t be manipulated in much the same way that when you were editing a scene — forget about mocap — if you’re just cutting a scene between two people and you cut away from one actor to the other person in the scene and then you cut back in the end and the emotion has shifted in a way that doesn’t ring true to you, you feel like there’s some kind of discontinuity.

There’s an element of unforgiving translation to the mocap data that you sometimes can get away with and you sometimes can’t. It’s like anything with editing. Sometimes your mind can be tricked completely and you can cheat and other times the audience will spot the cheat a mile away and you have to run away from it. I would say probably 99 percent of the time you really need to maintain the integrity of what you’re doing with the mocap data. Very often they say you can do anything with this technology. If someone says this technology will allow you to do anything, they’re lying to you because the limitations aren’t the technology, it’s about the reality that the audience demands: that’s your limitation. You have to honor that first and foremost. You may be able to do it technically but emotionally something is off.

HULLFISH: When you have a dialogue scene where you just got dailies and an empty timeline what is your approach. How do your assistants set up your bins for you.

FORD: I usually begin by watching all the material in the order that it was photographed for the most part because I like to see the continuity of the actor’s performance over the course of the shooting day and it also allows me to feel how the directors shape the performance over the course of the day. So I like to watch things in the order that they were shot and get a sense of what was changing over the course of the day based on what the directors might have been adjusting the actors. While I’m doing that, I’m making notes about moments of different shots that I might want to be in for particular moments in the scene. So whether that be a visual moment or a line of dialogue. I like to view things that way so in order to prepare for that my assistants will prepare the footage so that there is usually an “action only” string out in my bin and it has all the action that occurs. Everything is cut off: the slates and the rollout and all that sort of thing. And for the most part I start by looking at that material and breaking the scene up into three distinct acts, if it’s a long scene. If it’s a short scene, I’ll usually leave it in one. But in some cases, if it’s a long scene, I’ll break it up into three acts: a beginning middle and end so that I can work on each individual component as a separate little scenelet and then join them together.

But really it’s about watching the dailies and finding where I want to be in any particular moment and then stringing that together and then starting to realize that there are relationships between the performances that I might want to connect. In other words what choice has one actor made and what choices have the other actors made in terms of what they want to emphasize in the scene? And I always follow the actors choices as best I can initially as to what to emphasize, because when you’re editing, you can kind of make a scene about anything and sometimes if they’re just about the plot or who wants what from whom and there’s just the basics there, that can fulfill the demands of the scene for the for the audience in terms of understanding the story, but it might not bring the emotions to the fore it might not show all the nuance you need to get the characters to really pop. So I like to follow what the actors have emphasized, but always in the back of my mind is: what are the story demands? Because the scene has to serve the story as well.

Once I’ve pulled all the pieces that I really like and the moments that I really like, I organize them in a chronological way based on the script and where they need to occur in the scene and I basically end up with a version of the scene that if you watch it, you can kind of follow it. But it’s all chopped up. It doesn’t have continuity or flow it’s all jumping around but all the moments are in the order that they should occur. And then I start shaping them and getting them tighter and tighter and tighter until they find a rhythms that I follow, and then after a couple hours depending on how long it takes to watch dailies I have a pretty decent rough cut of the scene and I put it away and look at it the next day because working it too hard the first day, I don’t get anywhere. I always need to have at least a few hours distance between a first pass of the scene and then the second pass usually gets me to where I can show it to the directors, after a little bit of sound refinement, but it does take a break from the scene to get it finished.

I can’t cut something and then walk it right to the directors. I’ve had do that occasionally and it’s always frustrating for me because I need that objectivity. We shot about 890 hours of footage on these two movies: for Avengers 3 and 4, so we were getting so much footage a day that it was overwhelming and you just had to keep up with the amount of cutting you couldn’t really take a break, but there was so much material that what you could do is just go on to the next thing and then come back to the first thing because there was always another pile of footage flying in the door. Sometimes we had three units running.

HULLFISH: From a logistical standpoint were you getting dailies on 4 at the same time you’re getting dailies for 3?

FORD: Well yeah. On any given week we could shoot scenes from three and four. Monday could be scenes for 3, Tuesday could be four. It was all over the place in terms of what we were shooting. It was all contingent on the actors’ schedules and location availability and what sets we were on. So there was a lot of back and forth and my co-editor Matt Schmidt and I would divide up material as it came in but eventually at a certain point the duties of the cutting Avengers 3 overtook priority wise the cutting of Avengers 4 so we began working pretty exclusively on Avengers 3 in December and Matt kept finishing the incoming material for Avengers 4 and then I sort of focused primarily on getting 3 up to speed with the directors when we needed to start dialing stuff in for the final edits, and then Matt continued to work on the fourth film and now that the third film’s going to be released we’ll both begin working in earnest on Avengers 4.

HULLFISH: So you were literally keeping up to camera on two different movies at the same time?

FORD: Well I’d love to say that we did that, but I don’t know that we ever really kept up to camera because of the sheer amount of footage coming in but we were really close. We also sometimes had to make decisions about what to cut based on what the directors needed to see because they’re going to be shooting the second part of it the next day, or whatever. So it was a really fluid process. But I will say that by the time we drilled down on the whole Avengers cycle and came back to finishing Avengers 3, we had a full cut of the other film ready. It needed a lot of work, but it was assembled and we were beginning refinements on it.

HULLFISH: That’s an incredible amount of needing to think through what needed to be done to keep both those moving at the same time.

FORD: I wouldn’t recommend it as a way to enjoy yourself but it was an interesting experience. I think we were all surprised at how much it took out of us. It was a hard process to shoot two films at once. It was necessary for a lot of reasons. It was grueling and I think it caused a lot of people to really rise to the occasion, so we got some incredible work out of a lot of people. But I would say it’s going to take me a while to recover.

HULLFISH: Can you give me a quick rundown of what the schedule was when you started principal photography and so on?

FORD: When we started shooting January 23, 2017. We basically continued shooting for about a year straight and then we began testing Avengers 3 in October but we began turning over visual effects as early as February March of 2017. So there were scenes that were cut and turned over in February March of 2017 and then we turn stuff over weekly to the visual effects vendors over the course of the year. Things are changing and we’re coming up with new ideas and there’s some shoots for Avengers 3 that didn’t occur until later in the year depending on when we had actor availability, so we were jumping around. This was the most discontinuous shoot but we had a pretty solid cut of the movie by October and we continued to refine it and come up with new ideas and we shot a couple of new scenes so we have ideas for at the end of the year.

We kept cutting until very late because we kept having ideas and thoughts and ended up restructuring the film a couple of times until it sort of clicked in. There was one day where I think we had a screening and we had just done a really massive restructure of the second act of the film and all of a sudden it clicked and it just started to sing and it was working. Firing on all cylinders and it was weird, it was like we were all watching a movie that was making itself like it had suddenly become self-aware. It locked into place and it was entertaining us. We were no longer in control. We were just a bunch of kids laughing at how great it was and feeling like we had nothing to do with it. This was in February, it started to become a joy for us to watch. It was a very difficult film to make because of the level of technical detail that was required. We have I think seven digital characters in the film. They all have to emote. they all have huge story points. They all have to interact with each other and It has to feel flawless.

HULLFISH: Can you describe some of what happened in that restructuring?

FORD: Talking about restructures before you’ve seen a film or even after you see the film is sometimes pointless because the audience won’t sense it — they won’t understand what was different. You could even screen the movie in its old version and the new version and the audience might not even perceive that much of a difference but what we were talking about before about the rhythm of the film and designing it so that it has dynamics so the characters handoff to each other in a way that feels like you peaks and valleys of excitement and emotion. That’s what it was. It was all that. It was all about creating a really awesome roller coaster ride and flow in the middle of the movie that took you up and down and up and down so that you really had a feeling of constantly being thrown into a new part of the story that seemed totally compelling, yet felt like you wanted to be there but was the last thing you expected.

So it was really finding the rhythms of that which involved breaking up stories in a slightly different way than we had in the screenplay phase and in the earlier edit and that’s all it was really. A lot of it was very simple but in order to do that you have to sometimes create new transitions which are difficult to make. They come from creating sound or music transitions or different cuts between scenes that weren’t originally meant to go together and once you solve those It really starts to pay dividends in terms of making the story feel like it’s moving along in the way that you always intended it to. And then I think the final piece of the puzzle was — as we were getting more and more of Alan Silvestri’s score in — the movie began to coalesce and connect better as it always does when Alan’s work goes into a film. He’s a master and what he gave to the movie just can’t be put into words. It was the cohesive glue that started to really make the thing thematically start to really pop. And it’s a great score it really. One of the best ones we’ve had in a Marvel movie.

HULLFISH: What do you think causes that need for structural changes that happen so often between a screenplay and the final film. The screenplay writers certainly are experts in story and there’s an entire team of people in development before the film goes into production that go over it with a fine tooth comb, yet there’s that old saw about: there’s the movie on the page, the movie that’s shot and the movie that goes up on the screen and they’re all different.

FORD: I think a lot of it has to do with: in a script very often you’re dealing in terms of plot and you’re dealing in terms of character. But the thing you can’t anticipate is the personality that the actors bring. You can think about it and you can write about it in a way that you write for a particular actor. But until you really feel what they bring to the party it’s always hard to tell what the tonality of each scene is going to be, especially in a film like Infinity War where we go from an incredibly intense emotional experience one moment and then we’ll be in something that’s sort of goofy and crazy and fun the next and then we’ll be into something it’s suspenseful and terrifying and then we’ll be back into the goofy. And it’s always difficult to know when you’re reading it which moments are going to feel light and which moments are going to feel heavy sometimes. The audience sometimes needs very little information to follow a story. And a lot of times screenplays give them too much and sometimes they don’t give them enough. And you can’t ever understand that until you get it up in front of it an audience.

It’s one of the mysteries of making a film. It’s been this way for every movie I’ve ever worked on — visual effects film or superhero movie or a drama or a docudrama or a comedy — you don’t know how it’s going to feel, how fast it’s going to feel or how slow it’s going to feel until you really get it up in front of an audience and watch it with a group. When you read it that it can feel tight and when you screen it it can feel slack. Likewise, you could have something that feels like it’s you know really confusing on the page but on screen all a sudden it’s clear as a bell and you don’t need as much to explain it. When you have an actor like Chris Pratt, you don’t know what that script’s going to do until he takes it and turns it into something new. There’s a number of actors in our cast that will do that. You can give them pages but they’re going to do something with it that you could not have imagined in a million years and it’s usually amazing. If there’s a secret sauce for the Marvel Cinematic Universe, it’s casting, because those people bring something to the party that you’ll never be able to anticipate. Part of what Joe and Anthony Russo are great at is leaving room for that to happen on set. And that’s really important because that’s where some of our best stuff comes from.

HULLFISH: How do you interact with Joe and Anthony?

FORD: I would cut material together and bring it to them on set and we’d look at stuff on set in rough cut form so we talk about what they were doing on a day to day basis and so they could see how their stuff was coming together. And then when we had time we’d get together and we’d watch the cut and we were about three months into the movie we watched a lot of it just because we wanted to see how it was coming together and we had some time — we were in Scotland shooting a sequence — and I put a cut together that you could watch it like a movie.

Everything that we hadn’t filmed yet was either covered by storyboards or layouts using mockups. We made our own little storyboards and kind of created a version of the scene that had yet to be shot, so that we could sit down and watch it as a movie. And it was very helpful because we could get a sense of how the flow was and what the pacing was going to be and we really could get a feel for what it might be like. I think we did that three or four times during the course of the film before we finished it and then once we had it mostly complete we sat down and watched it and then we would begin weekend sessions where we would get together and look at it to make notes. I wish we could have screened it more. Once they got back from shooting we really began the process of screening it a lot. I love those guys. It’s easy to work with them because we all kind of are in the same zone in terms of taste and there’s not a lot of arguing about what’s better and what’s not. It’s mostly about keeping each other up to speed on what the plan is.

HULLFISH: What are the difficulties in keeping your objectivity through all the screenings and changes?

FORD: The only way to keep objectivity is to screen for an audience that hasn’t seen it, because when you’re watching with a roomful of people who haven’t seen the movie, you objectively goes right back up to the top because you’re seeing it through their eyes and that served us really well. We did a lot of tests on this film and they were all very instrumental — not so much for what the people said afterward — people came out of them feeling good about the movie and when you test an Avengers movie the audiences is really having a good time. But what you take away from it is: Where were they restless? Where did they laugh? Where didn’t they laugh? But also you’re watching the film going, “oh my god I bet they don’t understand this.” Something occurs to you that I need to make this moment clear because they have no way of knowing. And so those screenings are the key.

FORD: The only way to keep objectivity is to screen for an audience that hasn’t seen it, because when you’re watching with a roomful of people who haven’t seen the movie, you objectively goes right back up to the top because you’re seeing it through their eyes and that served us really well. We did a lot of tests on this film and they were all very instrumental — not so much for what the people said afterward — people came out of them feeling good about the movie and when you test an Avengers movie the audiences is really having a good time. But what you take away from it is: Where were they restless? Where did they laugh? Where didn’t they laugh? But also you’re watching the film going, “oh my god I bet they don’t understand this.” Something occurs to you that I need to make this moment clear because they have no way of knowing. And so those screenings are the key.

What’s great about Marvel is we’ve got Kevin Feige who usually doesn’t see the film until after the director’s cut is pretty close to complete. He’s seen parts of it — as we show material and turn visual effects over — but he comes in and watches the movie after we’ve been working it for a few weeks and he has fresh eyes, but a complete and utter understanding of the story so it’s like having one of your strongest, most important collaborators show up with a lot of objectivity. It takes a village. It takes a team of people to keep everybody on track because you do lose objectivity and you lose it really fast. But there are techniques to getting it back.

HULLFISH: I would think sound effects play a big part in the rhythm and the pacing of the scenes. Are you cutting in sound effects yourself during picture cut?

FORD: I work with a sound designer, Shannon Mills, who’s a member of the team up at Skywalker Ranch and he and I worked together on every Marvel movie that I’ve done. He is a genius and has skills beyond all humans when it comes to creating sounds for movies. He makes sounds for me early on based on things that we talk about and sends them to me and sometimes I’ll cut them and sometimes I’ll send him a sequence and ask him to edit it if it’s in action scene, I’ll usually send them to him, but if it’s narrative sound effects and thematic sound effects we work on them together and then I cut them into the track. I maintain a very meticulous dub as we go along. We have no time to temp dubs on Marvel movies for previews so I do all the mixing for the previews and the movie doesn’t get mixed until the very end of the process and often visual effects aren’t even in yet, they’re still changing, so in some ways we design a rhythmic soundtrack that has to be bulletproof even if some of the visuals are changing a bit and we’re not sure about how things are exactly going to land. We have to be ready to adjust those at the last minute but I like to maintain a soundtrack with temp score or eventually — what’s even better — is the composer’s mocks begin coming in and we start adding those into the track.

We’re listening to a version of the movie that’s as close as possible to what it’s going to sound like what it’s finished because for my money it’s easily 50 percent if not more of the experience comes from the soundtrack, so I spend a lot of time working on the sound and I’m pretty fanatical when it comes to how precise we have to be about it because something can be working completely well and you change the soundtrack — same picture edit — and it falls apart and I need to maintain the effects we spent months creating and a lot of those are created by sound so absolutely sound design and mix is a hugely important part of our process. Besides Shannon we have Dan Laurie who shares the sound supervision credit and serves as ADR supervisor and then we have Tom Johnson and Juan Peralta — our re-recording mixers — they are absolutely brilliant. They are hilarious and gifted. They did a stunning job again finishing the sound on the movie is as important to the rhythm of the movie as the picture edit in terms of how a reel plays, and about those dynamics we were talking about earlier how those get delivered to the audience — it’s as much in the sound as it is in the picture.

HULLFISH: Thanks so much for your time.

FORD: Thanks. Nice to talk to you.

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish

The first 50 interviews in the series provided the material for the book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV Editors.” This is a unique book that breaks down interviews with many of the world’s best editors and organizes it into a virtual roundtable discussion centering on the topics editors care about. It is a powerful tool for experienced and aspiring editors alike. Cinemontage, CinemaEditor magazine and FirstFrame, the magazine for the Guild of British Film and TV editors, all gave it rave reviews. No other book provides the breadth of opinion and experience. Combined, the editors featured in the book have edited for over 1,000 years on many of the most iconic, critically acclaimed and biggest box office hits in the history of cinema.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now