Ron Howard has trusted the editing of all of his films to the long-time team of Dan Hanley, ACE and Mike Hill, ACE. Art of the Cut interviews them both about Howard’s latest epic, “In the Heart of the Sea.”

Ron Howard has delivered a consistent string of films that have spoken deeply to the American cinema audience. From his early efforts, like “Splash” (and my personal favorite, “Night Shift”) to critically acclaimed films like, “Apollo 13,” and “A Beautiful Mind.” Ron has trusted his vision to a pair of editors for the entire duration of his directorial career – a testament to the strength of his collaboration with Mike Hill, ACE and Dan Hanley, ACE. The team’s latest effort was, “In the Heart of the Sea,” the cinematic telling of the epic true-life story that inspired “Moby Dick.”

I spoke to Mike Hill and Dan Hanley in two separate interviews. This article combines those interviews into a virtual conversation. Not all questions were asked of both men.

HULLFISH: Dan, tell me about how your partnership with Mike began.

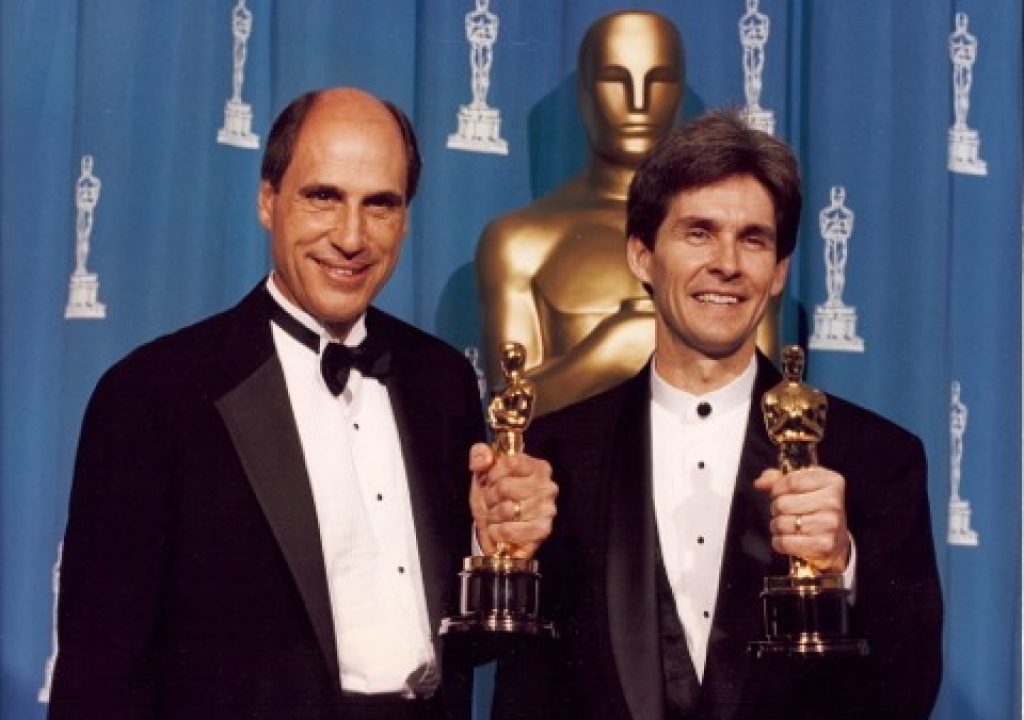

HANLEY: We (Hill, pictured left, Hanley, right) started back in 1982 on “Night Shift.” I’d worked previously with Ron with another editor, Robert Kern. When Ron was doing “Happy Days” during the hiatus he directed three movies of the week: “Cotton Candy,” “Skyward,” and “Through the Magic Pyramid.” So I was an assistant on those and was fortunate enough to have an editor that would let me edit as much as I had time for outside of assisting. So when “Night Shift” came along, Ron felt pretty confident that maybe I could find my way around. Robert Kern had a stroke right before the movie was supposed to start, so then Ron asked me if I knew anyone else and Ron must have gone to bat for Mike and I because we really didn’t have any credits. Ron came up with this idea where Robert Kern would be on as supervising editor and Mike and I cut under his supervision. That picture had a very quick turnaround I think we started shooting in January of that year and the movie came out in July.

HULLFISH: WOW!

HANLEY: Yeah, pretty quick. “Splash” was a pretty quick schedule and “Cocoon” turned out to be a pretty quick schedule also. It was supposed to come out in the fall and when the Zanucks saw the assembly after the Christmas break and said, “Wow. We should see what we can do to move this schedule up to the summer.

HULLFISH: Tell me what you think about your editing.

HANLEY: It’s always been a partnership for me. It’s great. It’s got to be the right person and obviously, Mike and I have worked together for a lot of years. (Pictured left Ron Howard, Dan Hanley, Steve Nash(NBA basketball star), Mike Hill. In Chicago in 2010, shooting “The Dillema”.) I think that’s based on trust and knowing that we’re always there for each other creatively. Either of us can come in and ask the other one a question right in the middle of a scene and get a perspective on it from someone with fresh eyes and not locked in on the dailies: “Have you thought about doing this?” and you say, “Oh! That’s so obvious!” You know those times where somebody gives you a note from the back of the room that’s so obvious? To me, competitively it’s a little irritating because you just can’t believe you didn’t see something that clear. You know what I mean?

HULLFISH: I’ve done that where I think I’ve cut something pretty well, and you hear some great suggestion and I think, “I’m an idiot.” I’m so glad that film-making is a collaborative process.

HANLEY: Yeah. Definitely. I think as you edit a little longer, at least for me, I accept that collaboration as part of the process more than when I was younger. Especially with Kern, when I was first cutting with him and I thought every cut I did was perfect. I didn’t want to hear any notes. And he said, “Well, you’re not going to last very long in this business. That’s kind of your job, to respond to notes. You better toughen up that skin a little bit, because it’s not about YOU, it’s about the final product.”

HULLFISH: Exactly right. Exactly right. So Mike it sounds like you’ve got a nice collaboration between you and Dan and the rest of the post team. Who are they?

HILL: Our first assistant, Simon Davis (pictured right), is British and he’s worked with us on several films – “Rush,” which was the Formula 1 film and he worked on some of our Da Vinci Code films – so he sort of ran the show as far as the assistant editors were concerned. The rest of our staff were British: second assistants Jeremy Richardson and Rob Sealey and the VFX editor, Derek Burgess. Dan Hanley did get there early and kind of spearheaded the whole set-up and stayed on longer than I did and finished up with the final mix.

HILL: Our first assistant, Simon Davis (pictured right), is British and he’s worked with us on several films – “Rush,” which was the Formula 1 film and he worked on some of our Da Vinci Code films – so he sort of ran the show as far as the assistant editors were concerned. The rest of our staff were British: second assistants Jeremy Richardson and Rob Sealey and the VFX editor, Derek Burgess. Dan Hanley did get there early and kind of spearheaded the whole set-up and stayed on longer than I did and finished up with the final mix.

HULLFISH: Were you on the production at all before shooting started?

HILL: Not before shooting started. I got there about the same time they started shooting. We were over in London. In Leavesden actually, where Warner Brothers has a studio. That was back in September of 2013. They had built a large tank outside and a replica of the Essex was in the tank and they shot a lot of scenes that were on-board scenes with a blue-screen background and wind machines and wave machines, which made it difficult to do a lot of dialogue in those scenes so it was all unusable dialogue, but we had to edit the scenes with that. The actors did some temporary ADR to try to smooth that out later. So it was one of those things were it was a hideous thing to look at…difficult to edit because it was so hard to hear.

HILL: Not before shooting started. I got there about the same time they started shooting. We were over in London. In Leavesden actually, where Warner Brothers has a studio. That was back in September of 2013. They had built a large tank outside and a replica of the Essex was in the tank and they shot a lot of scenes that were on-board scenes with a blue-screen background and wind machines and wave machines, which made it difficult to do a lot of dialogue in those scenes so it was all unusable dialogue, but we had to edit the scenes with that. The actors did some temporary ADR to try to smooth that out later. So it was one of those things were it was a hideous thing to look at…difficult to edit because it was so hard to hear.

HULLFISH: Talk to me about the challenges of working through that and needing to use your imagination to see what it WOULD become.

in-the-heart-of-the-sea-ITHOTS_EPK_FilmClip_WereHeadingIntoAStorm_h264_hd from Steve Hullfish on Vimeo.

HILL: It was very hard to hear and sometimes I couldn’t even tell what they were saying and I had to rely on the script and struggle through it. Shooting on digital, sometimes the amount of footage is just ridiculous. It’s very tedious. I call it drudge work, where you just have to cull out a lot of things that you don’t think you’ll need and that takes a long time, just to get it down to a working amount of footage where you can concentrate on structuring it. Those were the very first scenes that they shot and I wasn’t looking forward to each day those first few weeks. But once we got through that and got the scenes starting to work, then Ron was able to get the actors wild lines that we could put in, so we could hear what they were saying. That was very helpful. It was a struggle. One of those things you have to fight through and keep your focus.

HULLFISH: Before we get too far into that, let’s talk about the production and post-production studios. You were editing near set most of the time?

HILL: Yeah. The studio in Leavesden is a large facility. It was an old Rolls-Royce factory and Warner Brothers turned it into a studio and they have a big Harry Potter tour there. But we had all our editing rooms at the studio and all of the production people were there. So Ron Howard was real close by. He would drop in all the time … you know the routine.

HILL: Yeah. The studio in Leavesden is a large facility. It was an old Rolls-Royce factory and Warner Brothers turned it into a studio and they have a big Harry Potter tour there. But we had all our editing rooms at the studio and all of the production people were there. So Ron Howard was real close by. He would drop in all the time … you know the routine.

HULLFISH: So that was a lot of principal photography, then you went on location, right?

HILL: We were in Leavesden for two and a half months, into November, then the production crew moved to the Canary Islands off the coast of Africa and shot most of the ocean-going footage for most of the scenes where they were stranded on the ocean after the whale attack. So that provided us with all of the real ocean-going footage, which had to be blended in with the studio footage and all of the backgrounds had to be filled in on the blue-screen. They shot a on the replica as they sailed down there and back – shots from the ship out onto the ocean getting waves and sunsets and cloud formations. Then they shot all of the scenes where they were stranded on the island. It was nice to get the footage that was real and it was beautiful and it was pleasant to look at and it was a departure from what we were getting at the studio.

HULLFISH: How long did you cut after shooting? What was the schedule like?

HILL: When they finished at the Canary Islands it was right around Christmas. We took a little Christmas hiatus and then we always end up in Connecticut. Ron lives in Greenwich and we have a house that he bought that we turned into editing rooms in Greenwich. I was there until the end of May. By that time we had pretty much locked. Well, not totally. We had “latched” the editing…

HULLFISH: “Latched,” I like that. I’ll have to steal that term.

HILL: It was pretty close to what we ended up with but they had decided to shoot some additional footage which took place in summer-time and that was after I had left. But we were a good five months in Greenwich, honing it down and trimming and getting it in to shape. There were friendly screenings of family and friends. So we got some good input from those. It was the usual process we go through. By the fall that was all completed and the movie was ready to be released in March of this year but then Warner Brothers made the decision to move it down to December.

HILL: It was pretty close to what we ended up with but they had decided to shoot some additional footage which took place in summer-time and that was after I had left. But we were a good five months in Greenwich, honing it down and trimming and getting it in to shape. There were friendly screenings of family and friends. So we got some good input from those. It was the usual process we go through. By the fall that was all completed and the movie was ready to be released in March of this year but then Warner Brothers made the decision to move it down to December.

HULLFISH: I’m assuming this was Avid on an ISIS and you and Dan worked in separate suites.

HILL: Dan and I have our own suites and we don’t really see each other much during the initial editing process because we’re doing our own scenes. Then when Ron is with us when he’s done shooting, the three of us put our heads together and we work together more closely. Dan and I are comfortable with each other where there’s a scene that I cut and Dan might work on a little bit or vice versa. What we love about the two editor process – and Ron loves it too – is that we don’t have any problems taking a shot at the other guy’s work. If I get hung up on something and it’s not quite working, I’ll have Dan take a look at it and he might have a fresh perspective on it. It all works out pretty well.

HULLFISH: Tell me about the collaboration process. My movies have been co-edited so it’s interesting to me how people work together. How the work-load gets divided and how you pick scenes to work on.

HILL: It’s pretty simple really. From day one when the scenes start coming in, one of us will take the first one and the other guy will take the next one. On occasion, there are certain scenes that might appeal more to me and I’ll say, “Dan, do you mind if I take this one?” It might be some sort of action scene or just an interesting scene based on the dailies, and he’s fine with that. What we try to do though is to pinpoint the big set-piece scenes that are going to be the most difficult and try to make sure that those are divided up evenly between us, so one guy isn’t stuck with all of the tough scenes. That’s our guiding principal.

HILL: It’s pretty simple really. From day one when the scenes start coming in, one of us will take the first one and the other guy will take the next one. On occasion, there are certain scenes that might appeal more to me and I’ll say, “Dan, do you mind if I take this one?” It might be some sort of action scene or just an interesting scene based on the dailies, and he’s fine with that. What we try to do though is to pinpoint the big set-piece scenes that are going to be the most difficult and try to make sure that those are divided up evenly between us, so one guy isn’t stuck with all of the tough scenes. That’s our guiding principal.

HANLEY: Yeah, there was definitely passing back and forth. There might be certain scenes that had a lot of footage where you might go, “You know what, if there’s some trims and tweaking, go at it. But if it’s a re-construct or re-invent then let me just take a whack at it again before you have to suffer through educating yourself on all that footage.” So I would say it depended on the scenes. Sometimes in the early stages, you might pass a reel back and forth, but definitely in the later stages, stuff was getting based back and forth. And nobody had a problem with it. It’d be like, “Ron’s got an idea here, do you care?” “Nah, I don’t care. Go at it and let’s see what you come up with. But THIS is what I liked.” We both felt free to say, “This is what I liked and this is what I didn’t.” It was always about finding what’s right for the movie.

HANLEY: Yeah, there was definitely passing back and forth. There might be certain scenes that had a lot of footage where you might go, “You know what, if there’s some trims and tweaking, go at it. But if it’s a re-construct or re-invent then let me just take a whack at it again before you have to suffer through educating yourself on all that footage.” So I would say it depended on the scenes. Sometimes in the early stages, you might pass a reel back and forth, but definitely in the later stages, stuff was getting based back and forth. And nobody had a problem with it. It’d be like, “Ron’s got an idea here, do you care?” “Nah, I don’t care. Go at it and let’s see what you come up with. But THIS is what I liked.” We both felt free to say, “This is what I liked and this is what I didn’t.” It was always about finding what’s right for the movie.

HULLFISH: Do you try to keep your suites as similar as possible so it’s easy for Ron to jump back and forth?

HILL: We both have the same setups. (Hanley’s suite in Greenwich) We usually put our rooms apart and have the assistants in between, though in Greenwich it’s a small house and we’re actually right next door to each other. But at the studio we had it set up where we were at opposite ends of the hallway and we had our assistants in the middle. We each have big monitors for viewing when Ron comes in. The usual Avid set up.

HILL: We both have the same setups. (Hanley’s suite in Greenwich) We usually put our rooms apart and have the assistants in between, though in Greenwich it’s a small house and we’re actually right next door to each other. But at the studio we had it set up where we were at opposite ends of the hallway and we had our assistants in the middle. We each have big monitors for viewing when Ron comes in. The usual Avid set up.

HULLFISH: How does Ron work with you? How do you collaborate? How does he deal with watching dailies?

HILL: It’s kind of a dream scenario. He’s one of those directors who doesn’t need to be over your shoulder all the time. He likes for us to come up with our own approach and surprise him. He has very little input at the beginning. Like I said, he’ll give us brief notes on some of his take preferences, but that’s about it. During the shoot, we’ll see him sometimes at night or sometimes on a weekend he might want to look at some finished sequences and give us some notes, but that’s about it. During the post, he’ll be around every day, but he’s usually on the phone or off doing something but he’ll come in and spend a few hours in the morning with Dan and myself altogether and we’ll look at the scenes. By this time the movie’s been assembled and we’ve got a long version and we’ll go through it scene by scene from beginning to end and that will take a week or so and we compile a huge amount of notes and we’ll just go to work on that. Then we won’t see him for a while unless there’s a sequence that he’s particularly worried about or wants to be involved, then he’ll sit with us and work for a while, but he doesn’t hover and he doesn’t distract you. Then once we’ve gone through all of the notes, we’ll go through the whole process again. So that’s pretty much the way we work together. He has a lot of trust in us as far as picking out performances. He’s often said that we coincide with his thinking on performance, so there’s not too much conflict there. We don’t always agree though. Sometimes he’ll pick a take that might work better and vice versa. There’s all that give and take. We have such a short hand over the years that it’s very smooth.

HILL: It’s kind of a dream scenario. He’s one of those directors who doesn’t need to be over your shoulder all the time. He likes for us to come up with our own approach and surprise him. He has very little input at the beginning. Like I said, he’ll give us brief notes on some of his take preferences, but that’s about it. During the shoot, we’ll see him sometimes at night or sometimes on a weekend he might want to look at some finished sequences and give us some notes, but that’s about it. During the post, he’ll be around every day, but he’s usually on the phone or off doing something but he’ll come in and spend a few hours in the morning with Dan and myself altogether and we’ll look at the scenes. By this time the movie’s been assembled and we’ve got a long version and we’ll go through it scene by scene from beginning to end and that will take a week or so and we compile a huge amount of notes and we’ll just go to work on that. Then we won’t see him for a while unless there’s a sequence that he’s particularly worried about or wants to be involved, then he’ll sit with us and work for a while, but he doesn’t hover and he doesn’t distract you. Then once we’ve gone through all of the notes, we’ll go through the whole process again. So that’s pretty much the way we work together. He has a lot of trust in us as far as picking out performances. He’s often said that we coincide with his thinking on performance, so there’s not too much conflict there. We don’t always agree though. Sometimes he’ll pick a take that might work better and vice versa. There’s all that give and take. We have such a short hand over the years that it’s very smooth.

HULLFISH: How interested is Ron in your reasons for choosing a shot? Is that what helps sell a cut?

CLICK “NEXT” BELOW TO CONTINUE THE ARTICLE

in-the-heart-of-the-sea-ITHOTS_EPK_FilmClip_PrepareToAbandonShip_h264_hd from Steve Hullfish on Vimeo.

HANLEY: I think probably any director with an editor they’ve worked with for a while, builds a trust and I think that trust is really important in any part of the business, whether it be the director with the actors or the director with the producer or the producer with the studio. A lot of it is based on trust – whatever job they’re doing – they’re going at it the best they can and to me it’s always amazing that a lot of us in the film business are left to our own devices and responsibilities. There’s something about the people that do this work, whether it’s production design or someone on the set, everybody’s got to do their thing with some supervision but not a lot of “right on top of you” supervision. So with Ron over the years, he knows that we’re really going to dig in there and look for the best performance. He has certain things in mind. He gives us notes but not a lot of notes. He really wants to see what we come up with. We’ll talk to him pretty frequently, when we have questions, or “What’s your take on this?” or “Did you have something specific in mind here?” but for the most part I like the fact that he just lets us go at the scene. When he comes in, he’s looking at it and he’s got something in mind and it’s pretty easy and quick to start running the other takes to see what’s happening. I think it’s based on trust that we’re working hard to look for that best performance.

HANLEY: I think probably any director with an editor they’ve worked with for a while, builds a trust and I think that trust is really important in any part of the business, whether it be the director with the actors or the director with the producer or the producer with the studio. A lot of it is based on trust – whatever job they’re doing – they’re going at it the best they can and to me it’s always amazing that a lot of us in the film business are left to our own devices and responsibilities. There’s something about the people that do this work, whether it’s production design or someone on the set, everybody’s got to do their thing with some supervision but not a lot of “right on top of you” supervision. So with Ron over the years, he knows that we’re really going to dig in there and look for the best performance. He has certain things in mind. He gives us notes but not a lot of notes. He really wants to see what we come up with. We’ll talk to him pretty frequently, when we have questions, or “What’s your take on this?” or “Did you have something specific in mind here?” but for the most part I like the fact that he just lets us go at the scene. When he comes in, he’s looking at it and he’s got something in mind and it’s pretty easy and quick to start running the other takes to see what’s happening. I think it’s based on trust that we’re working hard to look for that best performance.

HULLFISH: Were there story and structure changes you needed to make between the Herman Melville listening scenes and the real Essex voyage?

HULLFISH: Were there story and structure changes you needed to make between the Herman Melville listening scenes and the real Essex voyage?

HANLEY: Yeah, definitely, and where they were placed. I know there was a little bit of a re-construct in the order of the Melville scenes and where they fell so that the pacing is sprinkled out throughout the movie, so you didn’t have long, long gaps without him. And Old man Nickerson was kind of the narrator of the story remembering the voyage from when he was a kid.

HILL: It was scripted similarly to the way it played out and they shot most of it in the early stages of the filming. We did a lot of the cutting on those scenes first and set them aside and integrated them into the film. They did re-shoot the opening scene where Melville meets Dickerson, (Herman Melville played by Ben Whishaw and Tom Nickerson played by Brendan Gleeson) in order to clarify things a little more. It was basically the same information as the original cut, but done in a little different way and a little more information was added I believe.

HILL: It was scripted similarly to the way it played out and they shot most of it in the early stages of the filming. We did a lot of the cutting on those scenes first and set them aside and integrated them into the film. They did re-shoot the opening scene where Melville meets Dickerson, (Herman Melville played by Ben Whishaw and Tom Nickerson played by Brendan Gleeson) in order to clarify things a little more. It was basically the same information as the original cut, but done in a little different way and a little more information was added I believe.

HULLFISH: You said it was scripted that way, but you also said you played around with it. So, I’m interested in how and why you felt you needed to diverge from the scripted version.

HILL: Usually they needed to stay in the spot they were scripted. Sometimes we would eliminate them (the Melville/Nickerson scenes) or shorten them way down and sometimes we would come back for a single line of dialogue or we would not go back to it visually, but we would use the dialogue as voice over narration instead of on-camera. Those were the kinds of decisions.

HILL: Usually they needed to stay in the spot they were scripted. Sometimes we would eliminate them (the Melville/Nickerson scenes) or shorten them way down and sometimes we would come back for a single line of dialogue or we would not go back to it visually, but we would use the dialogue as voice over narration instead of on-camera. Those were the kinds of decisions.

HULLFISH: Dan, Talk to me about the pacing at the beginning of the movie with the slower paced departure from of the Essex from the harbor in Nantucket and the faster paced sequence that follows it in the squall and how the pacing of one set up the pacing of the next.

in-the-heart-of-the-sea-ITHOTS_EPK_FilmClip_MakeSail_h264_hd from Steve Hullfish on Vimeo.

HANLEY: The Essex leaving the harbor was one of those scenes where there were multiple versions cut. Originally it was cut with them racing to get out of the harbor. There was almost a collision with another ship leaving the harbor. At this point the ships weren’t moving very quickly so it was hard to build tension with it. Audiences were looking at it saying, “Why don’t they just turn the boat?” So then we came up with the concept of just showing how much work it was getting a ship under way and out of the harbor. That’s when that scene really started to take shape. It took a few passes to figure out because it was shot a certain way and then we had to try to re-construct it and bend the scene to make it work like that. This, to me, is fun. It’s always a challenge to try to make something work differently than the way it was conceived. As far as pacing prior to the squall, I think that was to show the audience, “Hey, this is majestic. This is great.” Then the left turn of “Oh. Not so great.” So you’re seeing it from the eyes of the kid and he’s looking up to the Chris Hemsworth character and “Wow. This guy’s a great sailor. This is my first voyage.” And then all hell breaks loose. It was that setting up of “Wow, this is a wonderful thing.” No. “This is going to be tougher than I thought.” So pacing was definitely conceived with that in mind.

HULLFISH: I’m always fascinated by how much the story changes from the shooting script to the end of post. They don’t know how much the director and editor alter things in editing. Some of those changes are because editing is where you finally get to see the script play out over time and in motion. It sounded great in the script to have the two ships race out of the harbor… until you see how slow two sailing ships really move when they’re setting sail. Do you remember a specific scene where you needed to tweak the pacing or were there scenes that you changed the pacing once you saw it next to another scene that was either very fast or more stately?

HULLFISH: I’m always fascinated by how much the story changes from the shooting script to the end of post. They don’t know how much the director and editor alter things in editing. Some of those changes are because editing is where you finally get to see the script play out over time and in motion. It sounded great in the script to have the two ships race out of the harbor… until you see how slow two sailing ships really move when they’re setting sail. Do you remember a specific scene where you needed to tweak the pacing or were there scenes that you changed the pacing once you saw it next to another scene that was either very fast or more stately?

HANLEY: Oh yeah. Definitely. Plus, when you’re cutting the scenes, you could be cutting the scene and thinking it’s fantastic, right? But then when you put all the scenes together as a whole, then the perception of what you have changes. Scenes you thought were really good alone don’t lend themselves to moving the movie along when they’re assembled with other scenes. So then it’s the process of chipping away at your babies and the babies hit the cutting room floor. Assembling is great. Trying to figure out the speed and tempo of the movie is always pretty darn interesting.

HANLEY: Oh yeah. Definitely. Plus, when you’re cutting the scenes, you could be cutting the scene and thinking it’s fantastic, right? But then when you put all the scenes together as a whole, then the perception of what you have changes. Scenes you thought were really good alone don’t lend themselves to moving the movie along when they’re assembled with other scenes. So then it’s the process of chipping away at your babies and the babies hit the cutting room floor. Assembling is great. Trying to figure out the speed and tempo of the movie is always pretty darn interesting.

HILL: I don’t think I worry about pacing much at all when I’m initially cutting a scene together. I pretty much feel like that’s going to take care of itself when we get in to it with Ron and he’s in there with us. Especially back when we were editing on film, it’s better to leave it long and a little slower than it’s going to be because it’s easier to take away than to add back, especially when we were cutting on film. That stays with me, even now that we’re digital. Although I admit that cutting on the Avid, I do cut it tighter – more the way I think it should be – on the first pass. But I pace it up more initially than I used to.

HILL: I don’t think I worry about pacing much at all when I’m initially cutting a scene together. I pretty much feel like that’s going to take care of itself when we get in to it with Ron and he’s in there with us. Especially back when we were editing on film, it’s better to leave it long and a little slower than it’s going to be because it’s easier to take away than to add back, especially when we were cutting on film. That stays with me, even now that we’re digital. Although I admit that cutting on the Avid, I do cut it tighter – more the way I think it should be – on the first pass. But I pace it up more initially than I used to.

HULLFISH: I talked to Alan Bell about cutting the latest “Mockingjay” movie and he likes to cut standing in front of a big projector. Do you find that your sense of pace changes between looking at a small editing monitor and a bigger screen or monitor?

HANLEY: No. No. People have asked that before. No. I mean, it depends on the story being told and whatever you’re working on. To me, I don’t waiver in that thought process. I’m basing my pacing on the story I’m telling and what’s involved in that story, so if it’s on a smaller screen or a larger screen, that would be like saying if you did a feature and it went to TV are you going to re-cut it? No. Would I change the pacing for any of the HBO stuff if I was cutting it for the big screen? No. You mentioned Kirk Baxter and why he cut something the way he did. Well, he cut that based on the rhythm and the timing and the musicality of that scene. And in the course of the movie, I think that applies the same way. Within that movie there’s different phrases of music where some are fast paced and some are slow paced. That’s what makes the movie interesting is the different tempo within it.

HANLEY: No. No. People have asked that before. No. I mean, it depends on the story being told and whatever you’re working on. To me, I don’t waiver in that thought process. I’m basing my pacing on the story I’m telling and what’s involved in that story, so if it’s on a smaller screen or a larger screen, that would be like saying if you did a feature and it went to TV are you going to re-cut it? No. Would I change the pacing for any of the HBO stuff if I was cutting it for the big screen? No. You mentioned Kirk Baxter and why he cut something the way he did. Well, he cut that based on the rhythm and the timing and the musicality of that scene. And in the course of the movie, I think that applies the same way. Within that movie there’s different phrases of music where some are fast paced and some are slow paced. That’s what makes the movie interesting is the different tempo within it.

HILL: I’m not too dependent on the big screen. I like to have a look at it when I’m done with a sequence that I’ve cut. But I’m pretty much honed in on the Avid screens when I’m working. I just use the big monitor to view something when I’m done.

HULLFISH: Dan, you mentioned phrasing and musicicality, but you were talking about those as metaphors to the visuals, right?

HANLEY: To me, the picture editing has a musicality. There is a tempo. And if the tempo is correct, then when someone’s scoring it then that scene works. So there’s something to the mathematics to me at least. If you’re right, then the guy scoring the movie will come to you and say it works. And if it’s not, something’s bumping and that’s all based on rhythm.

HANLEY: To me, the picture editing has a musicality. There is a tempo. And if the tempo is correct, then when someone’s scoring it then that scene works. So there’s something to the mathematics to me at least. If you’re right, then the guy scoring the movie will come to you and say it works. And if it’s not, something’s bumping and that’s all based on rhythm.

HULLFISH: Was there a movie or a moment that really propelled you into wanting to be an editor?

HANLEY: My dad was in the industry, so I got to hang around sets a lot. He was an assistant editor on “Star Trek.” So when I was 12 years old I got to hang out on the set of the original “Star Trek” series with Shatner and Nimoy and the rest of the cast. I thought it was fantastic. I remember watching movies and being so enthralled by performance and watching good acting. Cool Hand Luke and Paul Newman’s performance is the first time I remember sitting back and taking notice of performance. You get to piece those performances together and see kind of acting day in and day out.Well not always but if you’re lucky. I used to hang out and with some of the editors down the hall that would let me sit and watch them. It was intriguing to me. I like watching people and how they interact. I’ve gotten caught sitting at parties and somebody will say, “What? Are you just sitting here watching everybody?” And I’d say, “Well, yeah I like it.” Editing is kind of like that in some regard.

HULLFISH: Absolutely. That describes me.

HANLEY: I mean, if you’re sitting in a room, where does your eye go? Everybody has a little different take on it, but good editors always know where the audience wants to look. That’s kind of the trick of it isn’t it?

HANLEY: I mean, if you’re sitting in a room, where does your eye go? Everybody has a little different take on it, but good editors always know where the audience wants to look. That’s kind of the trick of it isn’t it?

HULLFISH: Yeah. Talk to me about performance since you brought that up. I got into these interviews because of that Lupita N’yongo Oscar speech where she said, “I’d like to thank my silent partner in the edit room, Joe Walker.” And I thought, “That’s a guy I have to talk to.” For a lead actress to realize what he did for her performance.

HILL: Absolutely. I remember that too! Those kinds of things stand out I think when you’re an editor. The actors very seldom acknowledge what we do. It’s nice to hear that.

HANLEY: I think that kind of thing is fantastic. It wasn’t that long ago where we got the other side of that: leaving the good stuff on the floor. I think the craft is being more recognized for the contribution it makes to the finished movie. I mean, the director is the final auteur of the movie. He’s going to come in and he’s going to look at what we did. But it’s in the assembly and that process of going through all that film. If we don’t have a decent construct of it. You’re looking at multiple takes, re-sets, different camera angles. It’s so much fun to find the performance.

HANLEY: I think that kind of thing is fantastic. It wasn’t that long ago where we got the other side of that: leaving the good stuff on the floor. I think the craft is being more recognized for the contribution it makes to the finished movie. I mean, the director is the final auteur of the movie. He’s going to come in and he’s going to look at what we did. But it’s in the assembly and that process of going through all that film. If we don’t have a decent construct of it. You’re looking at multiple takes, re-sets, different camera angles. It’s so much fun to find the performance.

HULLFISH: It’s about finding the right moments, an actor will go out on a limb and sometimes that leads to amazing performances and sometimes failures and they’re depending on us to be the steward of that performance. The editor can alter or enhance the performance by choosing takes, changing timings, deciding on a reaction shot instead of playing something on camera…talk to me about being the steward of performance for the actor.

HILL: To me, that’s the number one responsibility of an editor. You can affect the performance in so many ways. I feel an obligation to the actor to get their very best moments in the film. Obviously, as you know, you can totally trash a great performance if you wanted to. But I love the process of going through and finding all the great moments that an actor gives you and then building that scene. To me it’s the ultimate part of the job. I’m so thankful that Ron has done so many types of films and worked with so many great actors. I would hate to be labeled as an action editor and never get to work on movies with just great acting.

HILL: To me, that’s the number one responsibility of an editor. You can affect the performance in so many ways. I feel an obligation to the actor to get their very best moments in the film. Obviously, as you know, you can totally trash a great performance if you wanted to. But I love the process of going through and finding all the great moments that an actor gives you and then building that scene. To me it’s the ultimate part of the job. I’m so thankful that Ron has done so many types of films and worked with so many great actors. I would hate to be labeled as an action editor and never get to work on movies with just great acting.

HANLEY: I remember when I was editing on film – you had to look at all the dailies and because of the mechanics of it, you really had to think about the road map and I’ve kind of stayed with that a little bit because the amount of the footage – I like to be able to check it all. I don’t want to miss any beats because it evolves for me as I’m cutting. I want to be able to react to that and adjust my thinking as I’m putting it together, so what I’ll end up doing is look at … let’s say you’ve got five printed takes from three cameras. I’ll run an A a B and a C camera, but I’ll run it from a couple of the takes and get an idea of what’s going on in a scene. So right off the bat, if I’ve got 10 hours of dailies on a given day then by doing that my dailies viewing is cut by 50 – 60 percent? Then I have an idea of how I’m going to start putting this thing together. So as I’m working to construct my first initial assembly I’m looking at the rest of the coverage as I go along. I’ll put a marker where I finished in that take and then I’ll start looking at the coverage from the other actors. I’ll go back to that take and I’ll pull that down and continue watching it to see where I’m going to pick it up again and sometimes I’ll high-speed through it knowing that I’m not going to be in that coverage. Or I’ll look at one take of it and say, “There’s really nothing in the composition of this shot.When I finish a scene I’ll put it aside and let it sit for a day or two so that when I come back and start fine-tuning it my perspective’s a little different. You know, as you’re putting it together sometimes you get a little myopic. Sometimes stepping away from it and looking at it later gives you a different perspective. So that’s kind of how I attack it when I look for performance.

HANLEY: I remember when I was editing on film – you had to look at all the dailies and because of the mechanics of it, you really had to think about the road map and I’ve kind of stayed with that a little bit because the amount of the footage – I like to be able to check it all. I don’t want to miss any beats because it evolves for me as I’m cutting. I want to be able to react to that and adjust my thinking as I’m putting it together, so what I’ll end up doing is look at … let’s say you’ve got five printed takes from three cameras. I’ll run an A a B and a C camera, but I’ll run it from a couple of the takes and get an idea of what’s going on in a scene. So right off the bat, if I’ve got 10 hours of dailies on a given day then by doing that my dailies viewing is cut by 50 – 60 percent? Then I have an idea of how I’m going to start putting this thing together. So as I’m working to construct my first initial assembly I’m looking at the rest of the coverage as I go along. I’ll put a marker where I finished in that take and then I’ll start looking at the coverage from the other actors. I’ll go back to that take and I’ll pull that down and continue watching it to see where I’m going to pick it up again and sometimes I’ll high-speed through it knowing that I’m not going to be in that coverage. Or I’ll look at one take of it and say, “There’s really nothing in the composition of this shot.When I finish a scene I’ll put it aside and let it sit for a day or two so that when I come back and start fine-tuning it my perspective’s a little different. You know, as you’re putting it together sometimes you get a little myopic. Sometimes stepping away from it and looking at it later gives you a different perspective. So that’s kind of how I attack it when I look for performance.

HULLFISH: What were some of your favorite performances?

CLICK “NEXT” BELOW TO CONTINUE THE ARTICLE

HILL: We did two movies with Russell Crowe, “Cinderella Man” and “Beautiful Mind.” Those stand out to me. Tom Hanks of course through the years. We’ve worked with him numerous times. Michael Keaton. On “Backdraft” all of Robert DeNiro’s scenes were really fun to work on. You see everything they do. They give you so many options on different takes. Like Crowe, on “Beautiful Mind,” he did multiple takes where he would alter the character’s behavior. In certain takes he’d be more manic, in certain takes he’d be more laid-back and left it up to use to build it. It was pretty fascinating to watch his approach.

in-the-heart-of-the-sea-ITHOTS_EPK_FilmClip_Landsman_h264_hd from Steve Hullfish on Vimeo.

HULLFISH: Some editors have decried the method of shooting with multiple cameras, because it means less of a variety of a performances.

HILL: Yeah. Ron has been almost always single camera, but lately has been using two cameras a lot for dialogue scenes. But he still gives us a number of takes. He probably averages four or five takes per set up, so we have a lot to work with.

HULLFISH: Anything else about performance? What draws you to a specific reading of a line?

HULLFISH: Anything else about performance? What draws you to a specific reading of a line?

HILL: With experience you get better at it. I go with my gut. The way a line is said, for me I immediately know this is the perfect take. The performance right here is what I want. A lot of it is gut instinct based on your experience over the years.

HULLFISH: You’d be amazed at some of the different approaches to the ways editors have their assistants set up their bins. Exactly how are your bins set up? How do you have them lay out the scene so it helps you the best?

HILL: I like Frame view and they set it up so that pretty much in script continuity order with pick-ups at the end. Sometimes I go to the text view and I’ll put in some notes for myself and I can look at the frame and get familiar with that and know where I have to go when I’m looking for a shot.

HANLEY: I’m a Frame view guy because Frame view to me is like Cliff Notes. You get a visual right there. I like the assistants to have the frame view over the various takes show a chronological look from the beginning of the scene to the end of the scene, so that when I look up quickly I remember, “Oh yeah. That’s the shot where they did that pickup.” I’ll change it as I’m going through, if I see something that looks a little better to me or something I want to have as a reminder. I like the bins set up: close-ups in one bin, mediums in another, or one actor in one bin and another actor in another bin. I’d rather toggle through bins than scroll up and down a giant bin. I know guys who throw stuff all in one bin and just scroll through it, but I’d rather have five small bins with decent sized frame views it’s always the quickest way for me to remember where the coverage is.

HANLEY: I’m a Frame view guy because Frame view to me is like Cliff Notes. You get a visual right there. I like the assistants to have the frame view over the various takes show a chronological look from the beginning of the scene to the end of the scene, so that when I look up quickly I remember, “Oh yeah. That’s the shot where they did that pickup.” I’ll change it as I’m going through, if I see something that looks a little better to me or something I want to have as a reminder. I like the bins set up: close-ups in one bin, mediums in another, or one actor in one bin and another actor in another bin. I’d rather toggle through bins than scroll up and down a giant bin. I know guys who throw stuff all in one bin and just scroll through it, but I’d rather have five small bins with decent sized frame views it’s always the quickest way for me to remember where the coverage is.

HULLFISH: What’s your approach to a scene? Not a complicated scene but just a simple scene. How do your assistants set up your bins. What do you ask them to do?

HILL: (pictured left) Now, in the digital age, with the Avid – Dan and I both learned the old-fashioned way, butt-splicing work-prints, so this is a whole different universe – my approach has evolved. My assistants first of all, they break down the footage into scenes. They organize the bins the way I like them. It’s pretty standard. I’ll have some notes that I’ve gotten from Ron from the set. He usually just gives us these simple notes about which takes he likes best or which moments he likes best within a take, so I have that to refer to, and then when they prepare the scene for me, I’ll take the bin and I’ll do a quick scan through and look at the footage fairly quickly and then I’ll dive in and put it together. What I love about the Avid is you can just try so many things quickly and I don’t worry about cutting it smoothly the first time through. I like to assemble it together and get the best moments in there and then go back through it and smooth it out later. My approach has evolved a little bit with each movie. I can get through things quicker each time and not waste as much time as I used to. It’s a matter of getting it together and looking at it and honing it.

HILL: (pictured left) Now, in the digital age, with the Avid – Dan and I both learned the old-fashioned way, butt-splicing work-prints, so this is a whole different universe – my approach has evolved. My assistants first of all, they break down the footage into scenes. They organize the bins the way I like them. It’s pretty standard. I’ll have some notes that I’ve gotten from Ron from the set. He usually just gives us these simple notes about which takes he likes best or which moments he likes best within a take, so I have that to refer to, and then when they prepare the scene for me, I’ll take the bin and I’ll do a quick scan through and look at the footage fairly quickly and then I’ll dive in and put it together. What I love about the Avid is you can just try so many things quickly and I don’t worry about cutting it smoothly the first time through. I like to assemble it together and get the best moments in there and then go back through it and smooth it out later. My approach has evolved a little bit with each movie. I can get through things quicker each time and not waste as much time as I used to. It’s a matter of getting it together and looking at it and honing it.

HULLFISH: How do you determine the first shot in the scene? How do you know when to cut?

HILL: A lot of it is gut. I like to look at the particular takes that Ron has pointed out, that he like the best, I look at those first. I make a note of the moments that I like the best and try to build the scene around those moments. I might even lay those down first when I start the scene… still not quite sure what my first shot is going to be all the time. But I’ve always found, and a lot of editors agree, that the toughest thing is to find that first shot. If Ron hasn’t designed an opening shot, sometimes he does. He’ll design a specific take to open the scene, then that’s easy. Once that opening shot is picked, then everything starts to roll from there in terms of building it. You know what I mean?

HILL: A lot of it is gut. I like to look at the particular takes that Ron has pointed out, that he like the best, I look at those first. I make a note of the moments that I like the best and try to build the scene around those moments. I might even lay those down first when I start the scene… still not quite sure what my first shot is going to be all the time. But I’ve always found, and a lot of editors agree, that the toughest thing is to find that first shot. If Ron hasn’t designed an opening shot, sometimes he does. He’ll design a specific take to open the scene, then that’s easy. Once that opening shot is picked, then everything starts to roll from there in terms of building it. You know what I mean?

HULLFISH: Yup. When you’re finding those little moments in takes, are you doing that with markers in the clip? Are you memorizing things? Writing them down?

HILL: I’m usually writing things down on a pad. The scene number. The take. Just a little note to myself. Sometimes I’ll use markers – a little red dot – on some of the takes.

HULLFISH: It sounds like you don’t bother with a selects reel or a KEM reel type deal.

HILL: For a usual dialogue scene I just dive in. Now if I have a big set-piece scene or a big action scene or a big dialogue scene with a lot of people talking I will do a selects roll that I can work off of that makes it easier to handle.

HILL: For a usual dialogue scene I just dive in. Now if I have a big set-piece scene or a big action scene or a big dialogue scene with a lot of people talking I will do a selects roll that I can work off of that makes it easier to handle.

HULLFISH: And when you do that, do you edit ON that selects reel, or do you pop it in your source monitor and use it as a source?

HILL: When I build the reel I’ll just use sections of takes and build it out. I try to keep them in some kind of script continuity. Then I will cut from that. I use it as a source knowing full well that I’ll probably have to dive back into the dailies as well.

HULLFISH: Of course.

HILL: But it will give me a starting point… to get things underway.

HULLFISH: Dan, you said you do a selects reel sometimes.

HANLEY: I do a combination. I figure out how I’m going to cut the scene – and to me, and I think a lot of guys would say this – figuring out the first shot or the first step…

HULLFISH: You gotta know where the scene starts.

HANLEY: Yeah. It starts to roll for me after that. So I’ve got my cut going and I’ve got my selects going at the same time on my record side. So then, if I like something, or if I want to add something later, I’m kind of leaving myself a bread-crumb trail with my selects roll. I may even have multiple selects rolls on my record side. I may string 15 line readings on a certain take, based on resets or what the director’s looking for. So out of that 15, I may like 5 of them, I may like 7. I’ll string those all together in my selects roll, then copy/paste it over to the source side and then attach it to my cut, then play the outgoing cut into each take and see how it flows based on what I’m doing in the previous coverage on the actors. By the process of elimination that seven becomes three and then I run those three takes against the rest of the cut until I find the one. Other times I know the one take that I like and I’m moving on. If I like a take and I don’t have any second thoughts about it, I’ll use it. Then, when the movie’s not in scene form any more and it’s in movie form, then I’ll double back and take a look at some of those other takes again. Because your sensibilities change.

HANLEY: Yeah. It starts to roll for me after that. So I’ve got my cut going and I’ve got my selects going at the same time on my record side. So then, if I like something, or if I want to add something later, I’m kind of leaving myself a bread-crumb trail with my selects roll. I may even have multiple selects rolls on my record side. I may string 15 line readings on a certain take, based on resets or what the director’s looking for. So out of that 15, I may like 5 of them, I may like 7. I’ll string those all together in my selects roll, then copy/paste it over to the source side and then attach it to my cut, then play the outgoing cut into each take and see how it flows based on what I’m doing in the previous coverage on the actors. By the process of elimination that seven becomes three and then I run those three takes against the rest of the cut until I find the one. Other times I know the one take that I like and I’m moving on. If I like a take and I don’t have any second thoughts about it, I’ll use it. Then, when the movie’s not in scene form any more and it’s in movie form, then I’ll double back and take a look at some of those other takes again. Because your sensibilities change.

HULLFISH: Your sensibilities change not just because you have a fresh perspective on a take, but because once the movie goes together in its complete form you also see the way the character’s supposed to change over time and if you used a great, super-emotional take in a scene, later on you see that the character needs to build to that point.

HULLFISH: Your sensibilities change not just because you have a fresh perspective on a take, but because once the movie goes together in its complete form you also see the way the character’s supposed to change over time and if you used a great, super-emotional take in a scene, later on you see that the character needs to build to that point.

HANLEY: Exactly. Exactly. And a great example of that is “Beautiful Mind.” Between Russell and Paul and Jennifer, that arc of that performance – watching how far Russel could go or not go and how early could that be versus the end of the movie. That is a perfect example of that.

HULLFISH: And really you had to be the one to modulate that performance even more than the actor could because he is shooting scenes out of order and counting on you. The actor has to give a certain amount of control over to the editor or director, because the way that performance is modulated is up to the editor and director during post.

HANLEY: Oh, absolutely. Think about it. If you’re an actor, you’re putting a lot of trust in the director and the editor to find that performance and I could see – if I was an actor – that you have a perception of what you did. That perception might not be any different than my perception when I am picking your performance initially. But then my perception changes later. Actors probably go through that same thing, “Oh my God, I had this really great take and it was fantastic, but when they come in the room – if they’re an actor/director or actor/producer – and they say, “That’s not as good as I remember. I see why you chose the other take.” Being an actor is tough, I mean really tough. They’re laying themselves out there emotionally and they can be made to look really good or not so good based on the takes. That would never happen, but when you’re looking from behind the curtain, they’re human beings the same as we are. They’re going to stumble. They’re going to have mis-steps. To me it doesn’t matter. If they nail one take that’s all they need. Because if they nail one take and miss seven, and we find it, they’re going to look great.

in-the-heart-of-the-sea-ITHOTS_EPK_FilmClip_HesMine_h264_hd from Steve Hullfish on Vimeo.

HULLFISH: Timing is also really an interesting part of performance. The smallest changes in the speed it takes to respond to another person reveal a lot. In my conversation with Kirk Baxter about “Gone Girl” there’s dialogue between Ben Affleck’s character and his twin sister. And that dialogue is very, very tight because it’s like they’re reading each others’ minds. The pacing of that performance is controlled by the editor.

HANLEY: Every scene is like that. Depending on what those characters are conveying in any given scene, that determines the pace of the movie. I kind of think, unless it’s a director who’s doing something REALLY stylized, that a given movie script, they all have a pace that’s right for that film. “How do you two guys (Hanley and Hill) get your scenes to match?” I say that they shouldn’t be able to tell the difference between two editors in the same room. If they can, then something’s wrong, because one of the guys is misinterpreting the movie and the rhythm of that movie.

HULLFISH: For a human being who’s used to hearing interaction with another human being, just the slightest hesitation or replying too early is enough to make a performance sound false.

HILL: Yup. Absolutely. I’ve often found that sometimes it’s better to look for those moments where they’re not doing everything perfectly. Where they do stumble a little bit and it makes it seem real. Sometimes it gets too perfect. If they snap into everything so perfectly it just doesn’t feel like real life.

HULLFISH: Let’s talk about the difficulties of cutting some of these scenes that are so visually effects heavy. So much of determining when a cut needs to happen is based on the motion inside the frame and if so much of that is special effects, how are you determining when to cut? Is it a lot of imagination? Is it pre-viz?

HANLEY: We had that on “Rush” also. A lot of it is imagination. A lot of that is pre-viz, so that leaves less to your imagination. And then you’re making adjustments as shots come in. A lot of it is, for example, with the whale stuff, you kind of went “I’ll have to adjust that shot when I see what the whale’s doing. I may have to trim.” But we knew the whale was being added to live action stuff, so the VFX guys were tied to what we were doing with live action, so it was a little bit of a give and take with that. With the squall, the same kind of thing. The boat’s moving around and I’ve got actors delivering lines, to me the choices were based on what was the best performance, what was the best composition to show that action and then sometimes thinking, “Wouldn’t this be better if I went back to a higher, wider shot to really show the scope of the squall and then punch back into it?” A combination of imagination and adapting as you start seeing shots come in from VFX. It has to be laid out pretty succinctly with pre-viz prior to going in to shooting. I’ll cut storyboards and Pre-vis together. I’ll plug them in as I’m waiting for shots.

HULLFISH: In many films, there’s a discussion of getting to a certain spot in the movie as early as possible. Not necessarily hitting a certain minute mark – like 10 minutes or 30 minutes – but knowing that there’s a critical moment that you really need to get the audience to as soon as is feasible. For this film, was that moment the sinking of the Essex?

CLICK “NEXT” BELOW TO CONTINUE THE ARTICLE

HILL: There’s always those discussions on every movie. Especially where there’s a big moment in the film. For us the big whale attack where he sinks the Essex is that moment. When you’ve got your first assembly, that moment happens a lot later because the entire movie is so much longer in every way than it’s ever going to be, but I think for us, in the course of trimming and honing down, that moment comes closer to where you want it and it felt pretty right the way it all came about. That big whale attack happens almost an hour in. Maybe not quite. But there are so many things that happen before that that are exciting scenes that it didn’t seem like a problem. We knew we had the whole survivor story coming up which would slow things down. The thing we wanted to make sure of is that the final third of the film not be tedious and still convey the hopelessness of the situation as best we could, but we were satisfied with the way it turned out.

HILL: There’s always those discussions on every movie. Especially where there’s a big moment in the film. For us the big whale attack where he sinks the Essex is that moment. When you’ve got your first assembly, that moment happens a lot later because the entire movie is so much longer in every way than it’s ever going to be, but I think for us, in the course of trimming and honing down, that moment comes closer to where you want it and it felt pretty right the way it all came about. That big whale attack happens almost an hour in. Maybe not quite. But there are so many things that happen before that that are exciting scenes that it didn’t seem like a problem. We knew we had the whole survivor story coming up which would slow things down. The thing we wanted to make sure of is that the final third of the film not be tedious and still convey the hopelessness of the situation as best we could, but we were satisfied with the way it turned out.

HILL: That’s always a consideration and it evolves as you go. You realize when you start testing the movie how much the audience is not getting or how much they need to know. We did play around a lot with those scenes and how they came in and out of the story. It was a lot of placing them in different places and the usual procedure you go through to make things flow together.

HILL: That’s always a consideration and it evolves as you go. You realize when you start testing the movie how much the audience is not getting or how much they need to know. We did play around a lot with those scenes and how they came in and out of the story. It was a lot of placing them in different places and the usual procedure you go through to make things flow together.

HANLEY: Seems to me that in the middles of movies people just seem to wander. Their attention spans – and I don’t want to sound like Old Father Time – but it seems you wonder, “Why are they bored there? This is really an interesting part of the movie?” Seems like a lot of time in the middle that seems to happen. And then again, as a quick anecdote, if the end is fantastic and the beginning is fantastic you kind of get away with stuff sometimes. For us, it was a little bit about getting them off the island from our original cut.

HULLFISH: Meaning that you needed to shorten that?

HANLEY: Basically it was shortening it. There was a lot of interesting stuff – survival stuff – on the island….walking around trying to find supplies and stuff that paid off visually. But it was like, “We get it. They’re stranded.” It wasn’t compelling enough for the audiences. So in that area we had to judiciously chip away at it until we ended up with something we liked. Sometimes you end up chipping away too much and then shorter feels longer, you know what I mean, because you didn’t get enough character or you didn’t get enough information, so it feels like a gloss-over. Then the scene becomes vulnerable because it feels like nothing. So that process of making the scene as compelling as you can and in the same process shortening it as much as you can is interesting to me.

HANLEY: Basically it was shortening it. There was a lot of interesting stuff – survival stuff – on the island….walking around trying to find supplies and stuff that paid off visually. But it was like, “We get it. They’re stranded.” It wasn’t compelling enough for the audiences. So in that area we had to judiciously chip away at it until we ended up with something we liked. Sometimes you end up chipping away too much and then shorter feels longer, you know what I mean, because you didn’t get enough character or you didn’t get enough information, so it feels like a gloss-over. Then the scene becomes vulnerable because it feels like nothing. So that process of making the scene as compelling as you can and in the same process shortening it as much as you can is interesting to me.

HULLFISH: A common thread in these interviews is the pace at which you parcel out information to the audience. As an editor, there’s the pace of a scene as it cuts from one shot to another. And there’s the overall pacing of the entire movie. But there’s also “How much information do we want to give the audience at this moment? Are we giving them too much or too little?”

HANLEY: Yeah. And sometimes, and with a lot of movies that are finished that are great movies, a lot of people after the fact say, “Oh, I would have done this or I would have paced that up.” Everybody’s an editor now. The lingo, it’s amazing in previews now, everybody’s saying “You should do this or do that. Did they think of using the score from such and such a movie?” The audience now is so incredibly smart that any nuance is not working for them, they’re all over that. Hey, the scriptwriter wrote it. The director directed it and it may not be exactly what you want but a lot of people like it.

HANLEY: Yeah. And sometimes, and with a lot of movies that are finished that are great movies, a lot of people after the fact say, “Oh, I would have done this or I would have paced that up.” Everybody’s an editor now. The lingo, it’s amazing in previews now, everybody’s saying “You should do this or do that. Did they think of using the score from such and such a movie?” The audience now is so incredibly smart that any nuance is not working for them, they’re all over that. Hey, the scriptwriter wrote it. The director directed it and it may not be exactly what you want but a lot of people like it.

HULLFISH: The movie can’t constantly be paced to the nth degree. It needs to breathe.

HANLEY: It needs to breathe once in a while. It does. Sometimes fast isn’t better.

HULLFISH: I interviewed Joe Walker twice – once after “12 Years a Slave.” We talked about pacing up the movie and “12 Years a Slave” has some really long shots in it…

HULLFISH: I interviewed Joe Walker twice – once after “12 Years a Slave.” We talked about pacing up the movie and “12 Years a Slave” has some really long shots in it…

HANLEY: (laughs)

HULLFISH: Let’s talk about pacing. As an example, the pacing of launching the Essex from the harbor and then the contrast of that pacing with the squall that they immediately run in to.

HILL: Actually, Dan did most of that. It was a continuous process. Ron was not happy with the way we left the harbor. The whole dynamic of most of the crew being kind of green and incompetent. Chase (Owen Chase played by Chris Hemsworth) was kind of the guy who knew what was going on. And the Nantucket money-men were kind of watching all of this and already starting to worry about it. We did a lot of ADR to try to get the point across that the Nantucket folks weren’t too happy with the way things were looking. There was a lot of work put in to those sequences and there was so much footage to work with, especially with the squall and the visual effects work that was involved and all of the detail of the ship and the waves hitting the ship. It was probably the most single part of the film that we kept going back to in order to get it to work to our satisfaction. It was probably one of the more difficult editing challenges. You probably wouldn’t expect that looking at the final movie.

HANLEY: It’s interesting to me too because of the pacing thing. It’s a different question on where you’re viewing it. If you’re viewing it in a theater, the pacing is different than if you’re watching it on an HBO series. Some of those HBO series, I’m absolutely eating up watching the performance and watching the way they’re letting it play and the actors and the performance and the tics and all that stuff. And on a big screen, sometimes that would be like, “Come on, let’s move it along.”

HANLEY: It’s interesting to me too because of the pacing thing. It’s a different question on where you’re viewing it. If you’re viewing it in a theater, the pacing is different than if you’re watching it on an HBO series. Some of those HBO series, I’m absolutely eating up watching the performance and watching the way they’re letting it play and the actors and the performance and the tics and all that stuff. And on a big screen, sometimes that would be like, “Come on, let’s move it along.”

HULLFISH: Talk to me about some of the difficulties. Was it in parceling out information? Or was it pacing? Or the amount of coverage?

HILL: Setting the right tone to start the movie out. We wanted a nice big action sequence to get things rolling and it wasn’t quite hitting home. It took a lot of work with the VFX people. They were working on the waves and the ocean dynamics and once that started to come together it started to work better for us. Dan did most of the work. He kept working on it. I was personally thankful that those scenes didn’t end up in my lap.

HILL: Setting the right tone to start the movie out. We wanted a nice big action sequence to get things rolling and it wasn’t quite hitting home. It took a lot of work with the VFX people. They were working on the waves and the ocean dynamics and once that started to come together it started to work better for us. Dan did most of the work. He kept working on it. I was personally thankful that those scenes didn’t end up in my lap.

HULLFISH: There are those scenes aren’t there? Talk to me about visual effects. I’ve spoken to some people with polar opposite ideas. Pietro Scalia on “The Martian” works with all his green-screen comped together roughly so there’s some kind of background. And I think it was Alan Bell on “Mockingjay” that prefers to edit with just the pure green-screen with no background plate because he feels that it keeps him “in the story” better than a poorly done temporary composite. When you’re dealing with SO much VFX, how do you deal with pacing? Do you rely on your imagination or what?

HILL: I don’t mind cutting with green-screen. It doesn’t bother me. I do use my imagination basically. Our assistants will composite it once the scene is edited to make it more viewable when we show it to Ron or to anyone.

HILL: I don’t mind cutting with green-screen. It doesn’t bother me. I do use my imagination basically. Our assistants will composite it once the scene is edited to make it more viewable when we show it to Ron or to anyone.

HULLFISH: Speaking of music, do you cut temp track in after your picture edit? Do you not use temp at all? Do you cut it in before you finish the picture cut? Are you getting tracks from the composer?

HANLEY: A combination of all of the above depending on – the last couple of movies, we’ve been relying on the assistants helping us a little more. Mike and I both like to do a lot of the music and sound work ourselves. It’s a combination. We’re chasing in score and trying it against the cut. And at some point the music editor is coming on and that’s good because it’s fresh input and they start throwing stuff up against the cut. To me, I’m cutting it based on the dialogue and the rhythm of that first. I’m not putting in music and cutting to the music if it’s a dialogue scene. I don’t want to do it that way because it seems that if I’m cutting the scene right the piece of music usually falls right. That doesn’t mean I’m not going to be shaving a piece here or there or making an adjustment but overall it seems to work that way. I’m always doing the initial cut based on the dialogue and the way that feels to me and then I’ll double back at some point and put music up against it and in those cases, if it’s an emotional thing, I may open up the edit at the end of the scene after the music goes in, because sometimes the scene will hold a little longer when the music goes in. When I had no music, I felt like I had to cut it earlier. That may adjust a bit. But temp music usually doesn’t make me adjust my cut much.

HANLEY: A combination of all of the above depending on – the last couple of movies, we’ve been relying on the assistants helping us a little more. Mike and I both like to do a lot of the music and sound work ourselves. It’s a combination. We’re chasing in score and trying it against the cut. And at some point the music editor is coming on and that’s good because it’s fresh input and they start throwing stuff up against the cut. To me, I’m cutting it based on the dialogue and the rhythm of that first. I’m not putting in music and cutting to the music if it’s a dialogue scene. I don’t want to do it that way because it seems that if I’m cutting the scene right the piece of music usually falls right. That doesn’t mean I’m not going to be shaving a piece here or there or making an adjustment but overall it seems to work that way. I’m always doing the initial cut based on the dialogue and the way that feels to me and then I’ll double back at some point and put music up against it and in those cases, if it’s an emotional thing, I may open up the edit at the end of the scene after the music goes in, because sometimes the scene will hold a little longer when the music goes in. When I had no music, I felt like I had to cut it earlier. That may adjust a bit. But temp music usually doesn’t make me adjust my cut much.

ART OF THE CUT DREAM TEAM PHOTO! Hanley,Hill, Elliot Graham, Lee Smith, Chris Dickens, Kirk Baxter, Angus Wall, at the ACE editing seminar before the Oscars, 2009.

HILL: I vary from scene to scene. It depends. We have a large temp library that we call on. For the most part I don’t like to cut anything thinking about music when I’m cutting, but once we have a bunch of scenes cut and we start to connect them, there are times when it seems like an obvious music sequence where the score is definitely going to be there, I’ll start to experiment with different temp scores and see how it starts to feel. And there have been rare occasions where I have found a really great piece of music and I’ll use it even when I’m cutting a sequence. I’ll lay down the music and I’ll cut the music with the sequence in the background, but I haven’t done that very often, but a couple of times it’s been usable. For the most part I don’t worry about the music until we have quite a few scenes cut.

HULLFISH: Can you remember a scene in a movie where you cut with music underneath?

HILL: We fell in love with the score of “The Way of the Gun” by Joe Kraemer and used it a lot in some movies in the early 2000s. We did a movie called “The Missing” with Tommie Lee Jones and Kate Blanchett. It was a Western and “The Way of the Gun” worked so well.

HILL: We fell in love with the score of “The Way of the Gun” by Joe Kraemer and used it a lot in some movies in the early 2000s. We did a movie called “The Missing” with Tommie Lee Jones and Kate Blanchett. It was a Western and “The Way of the Gun” worked so well.

HULLFISH: How much sound design were you doing early on to be able to make these scenes feel right? Is having sound design critical to getting a good rough cut or do you wait on that for later or even let someone like an assistant or the sound design team do that?

HILL: I like to do it myself if I have the time and I like to do it fairly quickly after I get the sequence together, especially if it’s a scene that needs that kind of help. Usually action scenes more than others. I like to fill in the backgrounds which helps to smooth out the cuts and then add some specific sound effect moments. If it’s a big, huge sequence and I don’t have much time to play with it I’ll ask one of the assistants to help it out with that, but I think it’s important to show it to Ron or to any producers with as much of that in there as possible.

Left to right: Music Editor Maarten Hofmeijer Mike Hill Composer Roque Banos Dan Hanley Ron Howard

HULLFISH: Did the sound team deliver audio effects to you early on or were you working from a sound effects library?

HILL: We have a pretty good sound effects library that we’ve accumulated and we also talk to the sound effects editors and they will send us specific things. If it’s generic backgrounds, we usually have that.

HULLFISH: I have a few clips from the movie. Care to comment on the editing of these?

in-the-heart-of-the-sea-ITHOTS_EPK_FilmClip_CaptainsDecision_h264_hd from Steve Hullfish on Vimeo.

HILL: It’s always nice when the final version of a scene is pretty much your first pass at it. That was the case with this one. (above) Apart from a few small trims here and there, the performance choices and rhythm and pacing are pretty close to the first cut of the scene. This was one of the first scenes to be shot, and I thought both actors did a nice job with it. I really enjoy cutting scenes like this. Fairly simple staging but nicely shot, with solid performances. The Captain is inexperienced and insecure and desperate to establish his authority over Chris Hemsworth’s first mate, and Ben Walker does a nice job of showing that. Chris’s takes were all very strong. He shows us that Chase is capable of subtle powers of persuasion.

in-the-heart-of-the-sea-ITHOTS_EPK_FilmClip_WhatWasThat_h264_hd from Steve Hullfish on Vimeo.

HILL: This is the start of the whale’s attack of the Essex. (above) I liked Ron’s approach to this scene. We let the audience see the giant whale approaching from the depths. One theory as to why the whale attacked the ship was because the sound of Chases’ hammering was similar to a sperm whale’s clicking sounds, and that drew him toward the Essex. So we really focused in on the close ups of Chase hammering. The scene also gives you the first sense of the enormity of the creature as we see him from above and below as he rams the Essex.

HULLFISH: Any other words of wisdom for editors?