Ron Howard has trusted the editing of all of his films to the long-time team of Dan Hanley, ACE and Mike Hill, ACE. Art of the Cut interviews them both about Howard’s latest epic, “In the Heart of the Sea.”

Ron Howard has delivered a consistent string of films that have spoken deeply to the American cinema audience. From his early efforts, like “Splash” (and my personal favorite, “Night Shift”) to critically acclaimed films like, “Apollo 13,” and “A Beautiful Mind.” Ron has trusted his vision to a pair of editors for the entire duration of his directorial career – a testament to the strength of his collaboration with Mike Hill, ACE and Dan Hanley, ACE. The team’s latest effort was, “In the Heart of the Sea,” the cinematic telling of the epic true-life story that inspired “Moby Dick.”

I spoke to Mike Hill and Dan Hanley in two separate interviews. This article combines those interviews into a virtual conversation. Not all questions were asked of both men.

HULLFISH: Dan, tell me about how your partnership with Mike began.

HULLFISH: WOW!

HANLEY: Yeah, pretty quick. “Splash” was a pretty quick schedule and “Cocoon” turned out to be a pretty quick schedule also. It was supposed to come out in the fall and when the Zanucks saw the assembly after the Christmas break and said, “Wow. We should see what we can do to move this schedule up to the summer.

HULLFISH: Tell me what you think about your editing.

HULLFISH: I’ve done that where I think I’ve cut something pretty well, and you hear some great suggestion and I think, “I’m an idiot.” I’m so glad that film-making is a collaborative process.

HANLEY: Yeah. Definitely. I think as you edit a little longer, at least for me, I accept that collaboration as part of the process more than when I was younger. Especially with Kern, when I was first cutting with him and I thought every cut I did was perfect. I didn’t want to hear any notes. And he said, “Well, you’re not going to last very long in this business. That’s kind of your job, to respond to notes. You better toughen up that skin a little bit, because it’s not about YOU, it’s about the final product.”

HULLFISH: Exactly right. Exactly right. So Mike it sounds like you’ve got a nice collaboration between you and Dan and the rest of the post team. Who are they?

HULLFISH: Were you on the production at all before shooting started?

HULLFISH: Talk to me about the challenges of working through that and needing to use your imagination to see what it WOULD become.

in-the-heart-of-the-sea-ITHOTS_EPK_FilmClip_WereHeadingIntoAStorm_h264_hd from Steve Hullfish on Vimeo.

HILL: It was very hard to hear and sometimes I couldn’t even tell what they were saying and I had to rely on the script and struggle through it. Shooting on digital, sometimes the amount of footage is just ridiculous. It’s very tedious. I call it drudge work, where you just have to cull out a lot of things that you don’t think you’ll need and that takes a long time, just to get it down to a working amount of footage where you can concentrate on structuring it. Those were the very first scenes that they shot and I wasn’t looking forward to each day those first few weeks. But once we got through that and got the scenes starting to work, then Ron was able to get the actors wild lines that we could put in, so we could hear what they were saying. That was very helpful. It was a struggle. One of those things you have to fight through and keep your focus.

HULLFISH: Before we get too far into that, let’s talk about the production and post-production studios. You were editing near set most of the time?

HULLFISH: So that was a lot of principal photography, then you went on location, right?

HILL: We were in Leavesden for two and a half months, into November, then the production crew moved to the Canary Islands off the coast of Africa and shot most of the ocean-going footage for most of the scenes where they were stranded on the ocean after the whale attack. So that provided us with all of the real ocean-going footage, which had to be blended in with the studio footage and all of the backgrounds had to be filled in on the blue-screen. They shot a on the replica as they sailed down there and back – shots from the ship out onto the ocean getting waves and sunsets and cloud formations. Then they shot all of the scenes where they were stranded on the island. It was nice to get the footage that was real and it was beautiful and it was pleasant to look at and it was a departure from what we were getting at the studio.

HULLFISH: How long did you cut after shooting? What was the schedule like?

HILL: When they finished at the Canary Islands it was right around Christmas. We took a little Christmas hiatus and then we always end up in Connecticut. Ron lives in Greenwich and we have a house that he bought that we turned into editing rooms in Greenwich. I was there until the end of May. By that time we had pretty much locked. Well, not totally. We had “latched” the editing…

HULLFISH: “Latched,” I like that. I’ll have to steal that term.

HULLFISH: I’m assuming this was Avid on an ISIS and you and Dan worked in separate suites.

HILL: Dan and I have our own suites and we don’t really see each other much during the initial editing process because we’re doing our own scenes. Then when Ron is with us when he’s done shooting, the three of us put our heads together and we work together more closely. Dan and I are comfortable with each other where there’s a scene that I cut and Dan might work on a little bit or vice versa. What we love about the two editor process – and Ron loves it too – is that we don’t have any problems taking a shot at the other guy’s work. If I get hung up on something and it’s not quite working, I’ll have Dan take a look at it and he might have a fresh perspective on it. It all works out pretty well.

HULLFISH: Tell me about the collaboration process. My movies have been co-edited so it’s interesting to me how people work together. How the work-load gets divided and how you pick scenes to work on.

HULLFISH: Do you try to keep your suites as similar as possible so it’s easy for Ron to jump back and forth?

HULLFISH: How does Ron work with you? How do you collaborate? How does he deal with watching dailies?

HULLFISH: How interested is Ron in your reasons for choosing a shot? Is that what helps sell a cut?

CLICK “NEXT” BELOW TO CONTINUE THE ARTICLE

in-the-heart-of-the-sea-ITHOTS_EPK_FilmClip_PrepareToAbandonShip_h264_hd from Steve Hullfish on Vimeo.

HANLEY: Yeah, definitely, and where they were placed. I know there was a little bit of a re-construct in the order of the Melville scenes and where they fell so that the pacing is sprinkled out throughout the movie, so you didn’t have long, long gaps without him. And Old man Nickerson was kind of the narrator of the story remembering the voyage from when he was a kid.

HULLFISH: You said it was scripted that way, but you also said you played around with it. So, I’m interested in how and why you felt you needed to diverge from the scripted version.

HULLFISH: Dan, Talk to me about the pacing at the beginning of the movie with the slower paced departure from of the Essex from the harbor in Nantucket and the faster paced sequence that follows it in the squall and how the pacing of one set up the pacing of the next.

in-the-heart-of-the-sea-ITHOTS_EPK_FilmClip_MakeSail_h264_hd from Steve Hullfish on Vimeo.

HANLEY: The Essex leaving the harbor was one of those scenes where there were multiple versions cut. Originally it was cut with them racing to get out of the harbor. There was almost a collision with another ship leaving the harbor. At this point the ships weren’t moving very quickly so it was hard to build tension with it. Audiences were looking at it saying, “Why don’t they just turn the boat?” So then we came up with the concept of just showing how much work it was getting a ship under way and out of the harbor. That’s when that scene really started to take shape. It took a few passes to figure out because it was shot a certain way and then we had to try to re-construct it and bend the scene to make it work like that. This, to me, is fun. It’s always a challenge to try to make something work differently than the way it was conceived. As far as pacing prior to the squall, I think that was to show the audience, “Hey, this is majestic. This is great.” Then the left turn of “Oh. Not so great.” So you’re seeing it from the eyes of the kid and he’s looking up to the Chris Hemsworth character and “Wow. This guy’s a great sailor. This is my first voyage.” And then all hell breaks loose. It was that setting up of “Wow, this is a wonderful thing.” No. “This is going to be tougher than I thought.” So pacing was definitely conceived with that in mind.

HULLFISH: I talked to Alan Bell about cutting the latest “Mockingjay” movie and he likes to cut standing in front of a big projector. Do you find that your sense of pace changes between looking at a small editing monitor and a bigger screen or monitor?

HILL: I’m not too dependent on the big screen. I like to have a look at it when I’m done with a sequence that I’ve cut. But I’m pretty much honed in on the Avid screens when I’m working. I just use the big monitor to view something when I’m done.

HULLFISH: Dan, you mentioned phrasing and musicicality, but you were talking about those as metaphors to the visuals, right?

HULLFISH: Was there a movie or a moment that really propelled you into wanting to be an editor?

HANLEY: My dad was in the industry, so I got to hang around sets a lot. He was an assistant editor on “Star Trek.” So when I was 12 years old I got to hang out on the set of the original “Star Trek” series with Shatner and Nimoy and the rest of the cast. I thought it was fantastic. I remember watching movies and being so enthralled by performance and watching good acting. Cool Hand Luke and Paul Newman’s performance is the first time I remember sitting back and taking notice of performance. You get to piece those performances together and see kind of acting day in and day out.Well not always but if you’re lucky. I used to hang out and with some of the editors down the hall that would let me sit and watch them. It was intriguing to me. I like watching people and how they interact. I’ve gotten caught sitting at parties and somebody will say, “What? Are you just sitting here watching everybody?” And I’d say, “Well, yeah I like it.” Editing is kind of like that in some regard.

HULLFISH: Absolutely. That describes me.

HULLFISH: Yeah. Talk to me about performance since you brought that up. I got into these interviews because of that Lupita N’yongo Oscar speech where she said, “I’d like to thank my silent partner in the edit room, Joe Walker.” And I thought, “That’s a guy I have to talk to.” For a lead actress to realize what he did for her performance.

HILL: Absolutely. I remember that too! Those kinds of things stand out I think when you’re an editor. The actors very seldom acknowledge what we do. It’s nice to hear that.

HULLFISH: It’s about finding the right moments, an actor will go out on a limb and sometimes that leads to amazing performances and sometimes failures and they’re depending on us to be the steward of that performance. The editor can alter or enhance the performance by choosing takes, changing timings, deciding on a reaction shot instead of playing something on camera…talk to me about being the steward of performance for the actor.

HULLFISH: What were some of your favorite performances?

CLICK “NEXT” BELOW TO CONTINUE THE ARTICLE

HILL: We did two movies with Russell Crowe, “Cinderella Man” and “Beautiful Mind.” Those stand out to me. Tom Hanks of course through the years. We’ve worked with him numerous times. Michael Keaton. On “Backdraft” all of Robert DeNiro’s scenes were really fun to work on. You see everything they do. They give you so many options on different takes. Like Crowe, on “Beautiful Mind,” he did multiple takes where he would alter the character’s behavior. In certain takes he’d be more manic, in certain takes he’d be more laid-back and left it up to use to build it. It was pretty fascinating to watch his approach.

in-the-heart-of-the-sea-ITHOTS_EPK_FilmClip_Landsman_h264_hd from Steve Hullfish on Vimeo.

HULLFISH: Some editors have decried the method of shooting with multiple cameras, because it means less of a variety of a performances.

HILL: Yeah. Ron has been almost always single camera, but lately has been using two cameras a lot for dialogue scenes. But he still gives us a number of takes. He probably averages four or five takes per set up, so we have a lot to work with.

HILL: With experience you get better at it. I go with my gut. The way a line is said, for me I immediately know this is the perfect take. The performance right here is what I want. A lot of it is gut instinct based on your experience over the years.

HULLFISH: You’d be amazed at some of the different approaches to the ways editors have their assistants set up their bins. Exactly how are your bins set up? How do you have them lay out the scene so it helps you the best?

HILL: I like Frame view and they set it up so that pretty much in script continuity order with pick-ups at the end. Sometimes I go to the text view and I’ll put in some notes for myself and I can look at the frame and get familiar with that and know where I have to go when I’m looking for a shot.

HULLFISH: What’s your approach to a scene? Not a complicated scene but just a simple scene. How do your assistants set up your bins. What do you ask them to do?

HULLFISH: How do you determine the first shot in the scene? How do you know when to cut?

HULLFISH: Yup. When you’re finding those little moments in takes, are you doing that with markers in the clip? Are you memorizing things? Writing them down?

HILL: I’m usually writing things down on a pad. The scene number. The take. Just a little note to myself. Sometimes I’ll use markers – a little red dot – on some of the takes.

HULLFISH: It sounds like you don’t bother with a selects reel or a KEM reel type deal.

HULLFISH: And when you do that, do you edit ON that selects reel, or do you pop it in your source monitor and use it as a source?

HILL: When I build the reel I’ll just use sections of takes and build it out. I try to keep them in some kind of script continuity. Then I will cut from that. I use it as a source knowing full well that I’ll probably have to dive back into the dailies as well.

HULLFISH: Of course.

HILL: But it will give me a starting point… to get things underway.

HULLFISH: Dan, you said you do a selects reel sometimes.

HANLEY: I do a combination. I figure out how I’m going to cut the scene – and to me, and I think a lot of guys would say this – figuring out the first shot or the first step…

HULLFISH: You gotta know where the scene starts.

HANLEY: Exactly. Exactly. And a great example of that is “Beautiful Mind.” Between Russell and Paul and Jennifer, that arc of that performance – watching how far Russel could go or not go and how early could that be versus the end of the movie. That is a perfect example of that.

HULLFISH: And really you had to be the one to modulate that performance even more than the actor could because he is shooting scenes out of order and counting on you. The actor has to give a certain amount of control over to the editor or director, because the way that performance is modulated is up to the editor and director during post.

HANLEY: Oh, absolutely. Think about it. If you’re an actor, you’re putting a lot of trust in the director and the editor to find that performance and I could see – if I was an actor – that you have a perception of what you did. That perception might not be any different than my perception when I am picking your performance initially. But then my perception changes later. Actors probably go through that same thing, “Oh my God, I had this really great take and it was fantastic, but when they come in the room – if they’re an actor/director or actor/producer – and they say, “That’s not as good as I remember. I see why you chose the other take.” Being an actor is tough, I mean really tough. They’re laying themselves out there emotionally and they can be made to look really good or not so good based on the takes. That would never happen, but when you’re looking from behind the curtain, they’re human beings the same as we are. They’re going to stumble. They’re going to have mis-steps. To me it doesn’t matter. If they nail one take that’s all they need. Because if they nail one take and miss seven, and we find it, they’re going to look great.

in-the-heart-of-the-sea-ITHOTS_EPK_FilmClip_HesMine_h264_hd from Steve Hullfish on Vimeo.

HULLFISH: Timing is also really an interesting part of performance. The smallest changes in the speed it takes to respond to another person reveal a lot. In my conversation with Kirk Baxter about “Gone Girl” there’s dialogue between Ben Affleck’s character and his twin sister. And that dialogue is very, very tight because it’s like they’re reading each others’ minds. The pacing of that performance is controlled by the editor.

HANLEY: Every scene is like that. Depending on what those characters are conveying in any given scene, that determines the pace of the movie. I kind of think, unless it’s a director who’s doing something REALLY stylized, that a given movie script, they all have a pace that’s right for that film. “How do you two guys (Hanley and Hill) get your scenes to match?” I say that they shouldn’t be able to tell the difference between two editors in the same room. If they can, then something’s wrong, because one of the guys is misinterpreting the movie and the rhythm of that movie.

HULLFISH: For a human being who’s used to hearing interaction with another human being, just the slightest hesitation or replying too early is enough to make a performance sound false.

HILL: Yup. Absolutely. I’ve often found that sometimes it’s better to look for those moments where they’re not doing everything perfectly. Where they do stumble a little bit and it makes it seem real. Sometimes it gets too perfect. If they snap into everything so perfectly it just doesn’t feel like real life.

HULLFISH: Let’s talk about the difficulties of cutting some of these scenes that are so visually effects heavy. So much of determining when a cut needs to happen is based on the motion inside the frame and if so much of that is special effects, how are you determining when to cut? Is it a lot of imagination? Is it pre-viz?

HANLEY: We had that on “Rush” also. A lot of it is imagination. A lot of that is pre-viz, so that leaves less to your imagination. And then you’re making adjustments as shots come in. A lot of it is, for example, with the whale stuff, you kind of went “I’ll have to adjust that shot when I see what the whale’s doing. I may have to trim.” But we knew the whale was being added to live action stuff, so the VFX guys were tied to what we were doing with live action, so it was a little bit of a give and take with that. With the squall, the same kind of thing. The boat’s moving around and I’ve got actors delivering lines, to me the choices were based on what was the best performance, what was the best composition to show that action and then sometimes thinking, “Wouldn’t this be better if I went back to a higher, wider shot to really show the scope of the squall and then punch back into it?” A combination of imagination and adapting as you start seeing shots come in from VFX. It has to be laid out pretty succinctly with pre-viz prior to going in to shooting. I’ll cut storyboards and Pre-vis together. I’ll plug them in as I’m waiting for shots.

HULLFISH: In many films, there’s a discussion of getting to a certain spot in the movie as early as possible. Not necessarily hitting a certain minute mark – like 10 minutes or 30 minutes – but knowing that there’s a critical moment that you really need to get the audience to as soon as is feasible. For this film, was that moment the sinking of the Essex?

CLICK “NEXT” BELOW TO CONTINUE THE ARTICLE

HANLEY: Seems to me that in the middles of movies people just seem to wander. Their attention spans – and I don’t want to sound like Old Father Time – but it seems you wonder, “Why are they bored there? This is really an interesting part of the movie?” Seems like a lot of time in the middle that seems to happen. And then again, as a quick anecdote, if the end is fantastic and the beginning is fantastic you kind of get away with stuff sometimes. For us, it was a little bit about getting them off the island from our original cut.

HULLFISH: Meaning that you needed to shorten that?

HULLFISH: A common thread in these interviews is the pace at which you parcel out information to the audience. As an editor, there’s the pace of a scene as it cuts from one shot to another. And there’s the overall pacing of the entire movie. But there’s also “How much information do we want to give the audience at this moment? Are we giving them too much or too little?”

HULLFISH: The movie can’t constantly be paced to the nth degree. It needs to breathe.

HANLEY: It needs to breathe once in a while. It does. Sometimes fast isn’t better.

HANLEY: (laughs)

HULLFISH: Let’s talk about pacing. As an example, the pacing of launching the Essex from the harbor and then the contrast of that pacing with the squall that they immediately run in to.

HILL: Actually, Dan did most of that. It was a continuous process. Ron was not happy with the way we left the harbor. The whole dynamic of most of the crew being kind of green and incompetent. Chase (Owen Chase played by Chris Hemsworth) was kind of the guy who knew what was going on. And the Nantucket money-men were kind of watching all of this and already starting to worry about it. We did a lot of ADR to try to get the point across that the Nantucket folks weren’t too happy with the way things were looking. There was a lot of work put in to those sequences and there was so much footage to work with, especially with the squall and the visual effects work that was involved and all of the detail of the ship and the waves hitting the ship. It was probably the most single part of the film that we kept going back to in order to get it to work to our satisfaction. It was probably one of the more difficult editing challenges. You probably wouldn’t expect that looking at the final movie.

HULLFISH: Talk to me about some of the difficulties. Was it in parceling out information? Or was it pacing? Or the amount of coverage?

HULLFISH: There are those scenes aren’t there? Talk to me about visual effects. I’ve spoken to some people with polar opposite ideas. Pietro Scalia on “The Martian” works with all his green-screen comped together roughly so there’s some kind of background. And I think it was Alan Bell on “Mockingjay” that prefers to edit with just the pure green-screen with no background plate because he feels that it keeps him “in the story” better than a poorly done temporary composite. When you’re dealing with SO much VFX, how do you deal with pacing? Do you rely on your imagination or what?

HULLFISH: Speaking of music, do you cut temp track in after your picture edit? Do you not use temp at all? Do you cut it in before you finish the picture cut? Are you getting tracks from the composer?

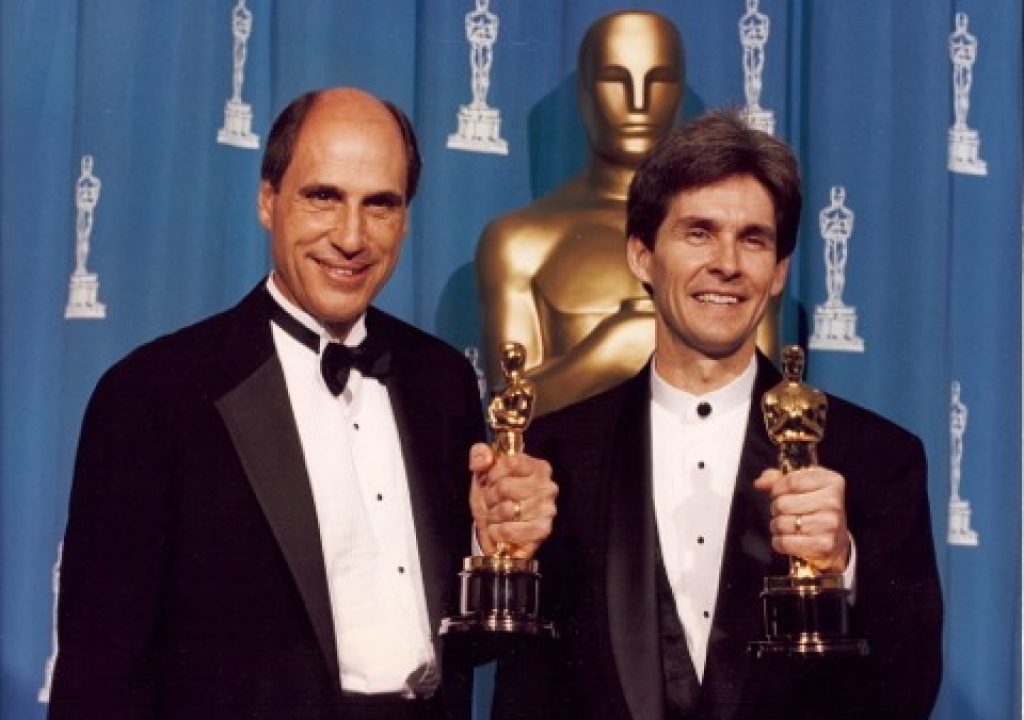

ART OF THE CUT DREAM TEAM PHOTO! Hanley,Hill, Elliot Graham, Lee Smith, Chris Dickens, Kirk Baxter, Angus Wall, at the ACE editing seminar before the Oscars, 2009.

HILL: I vary from scene to scene. It depends. We have a large temp library that we call on. For the most part I don’t like to cut anything thinking about music when I’m cutting, but once we have a bunch of scenes cut and we start to connect them, there are times when it seems like an obvious music sequence where the score is definitely going to be there, I’ll start to experiment with different temp scores and see how it starts to feel. And there have been rare occasions where I have found a really great piece of music and I’ll use it even when I’m cutting a sequence. I’ll lay down the music and I’ll cut the music with the sequence in the background, but I haven’t done that very often, but a couple of times it’s been usable. For the most part I don’t worry about the music until we have quite a few scenes cut.

HULLFISH: Can you remember a scene in a movie where you cut with music underneath?

HULLFISH: How much sound design were you doing early on to be able to make these scenes feel right? Is having sound design critical to getting a good rough cut or do you wait on that for later or even let someone like an assistant or the sound design team do that?

HILL: I like to do it myself if I have the time and I like to do it fairly quickly after I get the sequence together, especially if it’s a scene that needs that kind of help. Usually action scenes more than others. I like to fill in the backgrounds which helps to smooth out the cuts and then add some specific sound effect moments. If it’s a big, huge sequence and I don’t have much time to play with it I’ll ask one of the assistants to help it out with that, but I think it’s important to show it to Ron or to any producers with as much of that in there as possible.

Left to right: Music Editor Maarten Hofmeijer Mike Hill Composer Roque Banos Dan Hanley Ron Howard

HULLFISH: Did the sound team deliver audio effects to you early on or were you working from a sound effects library?

HILL: We have a pretty good sound effects library that we’ve accumulated and we also talk to the sound effects editors and they will send us specific things. If it’s generic backgrounds, we usually have that.

HULLFISH: I have a few clips from the movie. Care to comment on the editing of these?

in-the-heart-of-the-sea-ITHOTS_EPK_FilmClip_CaptainsDecision_h264_hd from Steve Hullfish on Vimeo.

HILL: It’s always nice when the final version of a scene is pretty much your first pass at it. That was the case with this one. (above) Apart from a few small trims here and there, the performance choices and rhythm and pacing are pretty close to the first cut of the scene. This was one of the first scenes to be shot, and I thought both actors did a nice job with it. I really enjoy cutting scenes like this. Fairly simple staging but nicely shot, with solid performances. The Captain is inexperienced and insecure and desperate to establish his authority over Chris Hemsworth’s first mate, and Ben Walker does a nice job of showing that. Chris’s takes were all very strong. He shows us that Chase is capable of subtle powers of persuasion.

in-the-heart-of-the-sea-ITHOTS_EPK_FilmClip_WhatWasThat_h264_hd from Steve Hullfish on Vimeo.

HILL: This is the start of the whale’s attack of the Essex. (above) I liked Ron’s approach to this scene. We let the audience see the giant whale approaching from the depths. One theory as to why the whale attacked the ship was because the sound of Chases’ hammering was similar to a sperm whale’s clicking sounds, and that drew him toward the Essex. So we really focused in on the close ups of Chase hammering. The scene also gives you the first sense of the enormity of the creature as we see him from above and below as he rams the Essex.

HULLFISH: Any other words of wisdom for editors?

HILL: I live in Nebraska and sometimes work with University of Nebraska film school. The kids ask me, “What do you really need to be a good editor?” And I tell them, “You need extreme patience and discipline to stay focused and if you have a big ego, you might have a problem because you’re not going to get a lot of glory as the editor, but what you contribute is huge to the final product.” So I try to get that across to the students. You learn that pretty quickly that you’re not going to get a lot of glory from the process. You really are behind the scenes making this thing work. I’m biased of course, but I think it’s one of the most essential aspects of making a film and you don’t even have a film unless you start honing away at all what they give you. They give you all the materials and then somebody’s got to work with it.

HULLFISH: Gentlemen, thanks for speaking with me and Art of the Cut today.

HANLEY: My pleasure.

HILL: It was great speaking with you.

For more Art of the Cut editing interviews, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish.