Harry Yoon has been a feature editor for the last 10 years. He has worked with some of the top Oscar-winning editors, including William Goldenberg, Stephen Mirrione and Tom Cross. Yoon’s own work includes, Let Go, Welcome to the Jungle, and Detroit. He was also the Additional Editor on First Man. In addition, he has a background as a VFX editor or VFX Assistant for films like Hunger Games, The Revenant, and Zero Dark Thirty.

I have interviewed Yoon previously with William Goldenberg for Detroit. This interview focuses on his recent work editing the film Best of Enemies.

(This interview was transcribed with SpeedScriber. Thanks to Martin Baker at Digital Heaven)

HULLFISH: Tell me a little bit about how you got hooked up with the director.

YOON: In 2011, I was an assistant editor under Stephen Mirrione on Hunger Games and that’s where I first met Robin Bissell, who was a producer on the film. Since then, I’d gone on to do a bit of editing. Robin is also good friends with Billy Goldenberg because Billy cut Seabiscuit, which Robin also produced. I had just finished working with Billy as an editor on Detroit when Robin asked Billy for recommendations on possible editors for his feature debut. That recommendation from Billy helped me get my foot in the door. Robin and I had a great meeting and a conversation about the project and I was lucky enough to get on board.

HULLFISH: Let’s talk about the schedule.

YOON: Principal photography started at the end of May 2017 and went through the beginning of July. They shot 6 weeks in Atlanta as a stand-in for Durham, North Carolina, which is where the story is set. We went through a traditional 10-week Director’s Cut through the beginning of September. We did a preview in October and pretty much mixed and locked the first version of the film by November 2017.

HULLFISH: So a basically a full year before this interview. (which we did in January 2019)

YOON: Yeah. Astute Films made the film without a distributor in place and then went through the winter looking for the right partner to distribute the film.

We had a very strong preview and the movie was on very solid footing. But it was very interesting to finish the film in November with the final mix and everything knowing that it was very likely — once we had a distributor — that there would be changes. I don’t think they closed a deal with a distributor until July 2018. So we actually ended up going back into the cutting room around August, about six months after we finished the film.

It was a crazy circumstance but kind of an amazing opportunity. How many times do you actually get a second pass at a cut with the benefit of time and distance to be able to see the film with new eyes?

I think both the director and I were very excited because when we went back in, it was so clear what could be trimmed or refined.

HULLFISH: Does that time allow the director to let go of things that he’s maybe been precious about? I know it seems self-evident, but how can time change your perception, when you haven’t done anything?

YOON: I think that was true for Robin. But it wasn’t just about letting go of things but also having the time to play around with things that had bothered him.

So for example, during our hiatus, he came up with a completely different opening for the film. Our first version was a fake “city booster film” for Durham that gave a strong sense of time and place before we start the action.

During the break, Robin found some archival audio from the real historical figures – CP Ellis and Ann Atwater – that was really engaging. Hearing their voices gave you a real sense of time and place but also a flavor of the larger-than-life characters you were about to see.

For me, another advantage of time off was that I got a chance to work on some other projects – most notably as an additional editor on First Man, with Tom Cross and Damien Chazelle. That film that had so much footage and our work on it involved a lot of reconfiguring, shortening and modification. There was a kind of rigor with which we played with the footage and made scenes do things that maybe they weren’t originally intended to do but NEEDED to do because of the restructuring. We often had to think “out of the box” to solve problems and it gave me a strong sense that almost anything is possible.

For example, when we went back into Best of Enemies, we actually even ended up moving a very critical emotional scene – where Ann is mourning something alone in her kitchen – from the middle of the movie to the end of the movie and having to do some visual effects with costume changes and things like that in order to make it work. But it just did wonders for that kind of balancing act that is needed in a two-handed story like our movie.

HULLFISH: To help any readers out about what you mean by two-handed story, this is really two main characters opposed to each other. You’re telling the story from two sides.

YOON: Yes. So the story is based upon an actual event in 1971 Durham, North Carolina. The series of events began with a fire at East End Elementary, which was a predominantly black school in Durham and most of the classrooms were rendered unusable. The city council didn’t come up with a solution fast enough to accommodate rebuilding that school, so the NAACP filed suit. And rather than rule on the suit the judge requested that a nearby academic who had done a series of community meetings called “charrettes” conduct a charrette in Durham on this issue. That academic, Bill Riddick, chose a very unlikely pair of co-chairs.

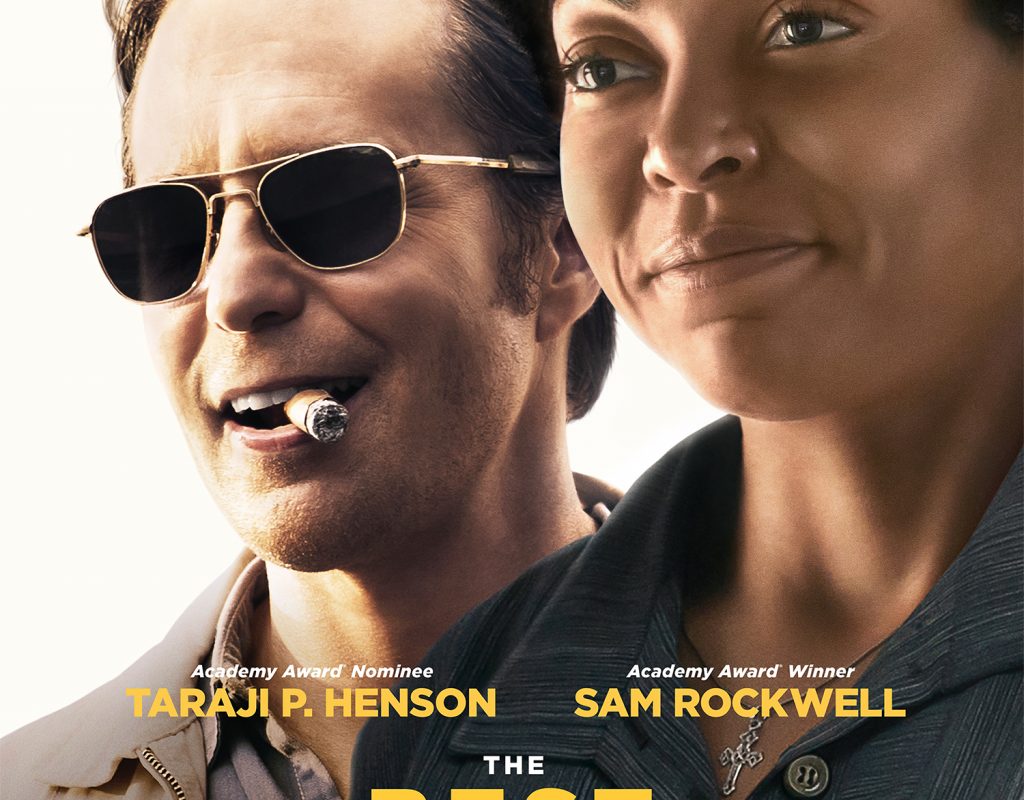

On the African-American side it was a very well-known local activist, Ann Atwater (she’s played by Taraji P. Henson in the movie), and then on the white side was the head of the KKK in Durham named CP Ellis, played by Sam Rockwell. And so the movie is the story of who these characters are at the beginning of that process and how they not only help the town, but they actually become lifelong friends. So it’s an almost unbelievable story seen through the lens of present-day tensions.

HULLFISH: You mentioned that you worked with Billy Goldenberg. He said that these kinds of projects — Detroit, 22 July — movies, like Best of Enemies — are the kinds of projects he wants to do and specifically seeks out. Do you have that feeling too? Or maybe you’re not quite at the level of Billy where you can just decide you’re only going to certain projects.

YOON: That’s the benefit of having mentors like Billy is that they give you a sense of what’s possible and where you want to aim for in your career. I’ve been really blessed in that the network of filmmakers I have had the chance to work with, give me access to some of those kinds of opportunities.

I love films that you can have conversations about how the story relates to the society we live in. You and I and every editor know how hard you need to work to make something good — to make something impactful — and not just something that’s watchable. Having that kind of motivation is part of what makes working on these kinds of projects so exciting.

HULLFISH: With The Post and with Detroit and with 22 July or Best of Enemies, it’s interesting to me that these movies are like parables. We can’t seem to about the issues that are at hand without saying, “OK, let’s talk about gun violence by going to Norway. Let’s start by race relations by going back to 1971. Let’s talk about the importance of the press by looking at Vietnam.”

HULLFISH: With The Post and with Detroit and with 22 July or Best of Enemies, it’s interesting to me that these movies are like parables. We can’t seem to about the issues that are at hand without saying, “OK, let’s talk about gun violence by going to Norway. Let’s start by race relations by going back to 1971. Let’s talk about the importance of the press by looking at Vietnam.”

YOON: I think that that’s part of what motivates the filmmakers as well, is that through time or through geography or maybe even through genre, there’s a way in which that slight layer of abstraction gives us the distance to think about our present in a different way.

And I think that that’s very much the intent of filmmakers like Kathryn Bigelow with Detroit.

For Best of Enemies, Robin made sure we recruited diverse audiences for the previews so we could gauge how they would react to the story and how we were telling it. It was heartening to see how they reacted so positively to a subject and relationship on which there seems so little possibility of dialogue.

HULLFISH: These are two characters that start very wide apart from each other and then they become close. There is a danger that either happens too fast or it takes too long. I would guess that it was important to regulate that. Was that something that happened just because of the script, or that you and the director had to consciously manage in post?

YOON: Calibrating the steps by which CP and Ann encounter each other, interact with each other, and ultimately change one another was something that we went back and forth quite a bit in our discussions. Part of it was that he knew so much of the biography of the real-life people and knew how much enmity there was in their previous interactions.

There is a scene at the beginning of the charette in which Ann addresses CP by name when she’s trying to make a point. Robin had a lot of problems with that because it conveyed a kind of familiarity and collegiality that he knew that they did not have at that time. Those are the kind of concerns we had.

This was especially important for Sam’s character, CP, because he’s the one that changes the most — both at home and interacting with members of the Klan and members of the power structure that exists in the town. We needed to lay down the seeds of what investment he had in his world-view and why he was invested in that way. Then show, beat by beat through the film, how the events and interactions with others start to break down the assumptions that he has about his opponents. I think it’s a testament to the brilliant job that Robin did in distilling the events chronicled in the book into a screenplay and movie that shows that process in a credible way.

HULLFISH: That’s super interesting. You have this character that you must have thought was abhorrent. I try to avoid conflict. I don’t know about you. But you are steeped in conflict from the moment you walk into the cutting room every day. Talk about the tension that you have to deal with psychologically just editing the scenes together.

YOON: When you’re portraying the head of the KKK, I think the challenge was how do we avoid being so sympathetic that it seems that we are condoning his beliefs but not take that so far that the character becomes alienated from the audience. And then the possibility of redemption doesn’t exist. One of the things that was a coup was casting someone like Sam Rockwell — who has shown, in Three Billboards, that it’s possible to show a character that’s convincing in terms of his abhorrent stances yet still is very human.

And also to show who Ann Atwater was, and how she got from a place where she couldn’t stomach being in the room with CP to a place where she shows an incredible amount of grace in helping CP’s family in a very substantial way

Balancing those two things: that’s where the tension was. How do we make sure that we are not being too sympathetic to CP’s character and balancing that with what we need to know about Ann’s character?

There’s a scene early on in which the Klan members shoot up a house with shotguns as a kind of warning for the owner. That was one of the most difficult scenes to cut because it was done as a kind of musical montage. And the music is supposed to serve this sort of ironic role, but we had to make sure that it was done in a way where you understood what was happening but that you weren’t enjoying it too much because after all, it is still the Klan shooting up somebody’s house! That was one of those watershed moments where we were trying to achieve that balance of how do we show subjectively that this is something that these guys are enjoying. But objectively not something that we should enjoy along with them. We iterated on it – especially in the song choice – quite a bit and did a lot of friends and family screenings to check whether we’d gotten this balance right.

HULLFISH: Did you edit in Georgia? How were you getting dailies

YOON: We were always in L.A. The cutting room was at EPS in Studio City. Even when we went back in for the re-cut recut we went to the same place.

HULLFISH: How was material getting to you? Aspera or something?

YOON: We were using Aspera to send us the onset dailies so we would have everything ready to go the next day. My assistant editor Emily Chiu would prep dailies and we’d usually be a half a day behind so while I waited, I would just be finishing up the previous day’s dailies.

HULLFISH: Did the actors give you different performance temperatures and how were you exploiting that in calibrating the tone of the film and where people were in their hatred or disgust or acceptance of each other?

YOON: The performance that we needed to do the most careful calibration on was actually Taraji as Ann Atwater. And I think part of it was Ann Atwater is this character who in real life was was very much larger than life. She was funny and big and would do outlandish things. Like in a meeting with one of the city council people — this is in the late 60s, early 70s — she actually reached across the desk, grabbed the phone that was in his hand and hit him in the head with it! So this is actually in one of our scenes and a lot of our friends and family audience couldn’t believe that a black woman would do that in Durham, North Carolina at the time but Ann had actually done it!

So, how do we stay true to the biographical truth of how big she was, but at the same time be careful about not making that bigness seem cartoonish, so that it distances you from somebody whose emotional life and who — as a character — we really needed the audience to invest in? And so we did a number of passes and screenings to try to keep some of the energy and the humor of who Ann was and yet be really careful about every look and movement that Taraji gave us to strike that balance.

HULLFISH: I think when I talked to you and Billy about Detroit you both talked about the responsibility of dealing with someone’s true life story. Is that something that you felt again with this one?

YOON: Absolutely. I researched the story by reading Osha Gray Davidson’s book and Robin would tell me stories in the cutting room about who these people were. I really started to see their fullness as human beings, and to understand both of them, because they both came up through such difficult personal circumstances in their childhood and into adulthood.

Yet, knowing that it’s a two-handed story and you have limited time, there were compromises that we needed to make in terms of how deeply do we go into Ann’s biography? How much of Ann’s faith practice can we show? Because in many ways it’s her faith that allows her the possibility of showing grace to her enemy in the way that she did. How much of CP’s economic circumstances can we show? Because so much of his defensiveness and his need to protect what he has is based upon the economic circumstances in which he grew up and found himself in?

There was so much more to tell about these larger than life characters, but obviously, we have to limit it to the essential elements that will help an audience get from point A to Point B for the sake of this particular telling of their story.

HULLFISH: Do you remember how long that first cut was?

YOON: Our first cut was about two hours and 40 minutes. And I think we ultimately got it down to just over two.

HULLFISH: What were the hard scenes that you really either had to fight to keep in the movie or one of the two of you wanted to keep but it didn’t get kept?

YOON: One of the scenes that got cut fairly late in our process is the chairperson’s office – the first time that Ann and CP find themselves alone in a room alone together. That was on day one of the charrette, where CP walks into the charrette chair’s office and sees these two desks facing each other and he immediately proceeds to turn his desk around so he doesn’t have to look at Ann. Ann Atwater walks in and says, “That’s okay CP, I’m used to white men turning their backs on me.” That kicks off a series of escalating interactions where they’re kind of annoying and taunting each other — all silently. So CP lights a cigar. Ann opens a bag of potato chips and crunches them loudly. It was just this escalating tension. That was a comic scene, but also to show where the characters begin in terms of their ability to stand each other.

The first cut was several minutes long in which we showed all of those actions and tried to sort of squeeze out as much of the humor as possible. But there was something about where it lived in the flow of the story that kept bumping for us. We kept going back to it and trimming it and trimming it shorter and shorter because I think we felt this sense of urgency to begin the charette.

Ultimately, we found that we couldn’t wait for this scene to play out, no matter how meaningful it was for the characters. So we ultimately ended up cutting it down to the bone where CP just walks in and sees the desks together and grimaces. It was just enough of a beat to log where they are in the flow of the overall relationship and story without slowing down the story.

HULLFISH: So, Detroit was shot kind of documentary style and this had much more normal or formal coverage. Does that change your assessment of dailies when you look at something that’s very documentary style compared to something that’s shot with more typical coverage?

YOON: Yes. I think in particular because (cinematographer) David Lanzenberg and Robin had designed some beautiful moving masters for the film as well as incorporating some special moves and crane shots into their coverage, so it was very clear — at least on an initial pass — what I needed to build around.

Obviously, once you have everything assembled, it becomes about balancing those things with time and pace and trying to stay ahead of the audience.

It was interesting how much more exacting Robin and I became with some of those special camera moves six months later. We thought we were already being un-precious about those shots but with the distance from the original production, we could be even more so. That was another way that we got to a leaner, more muscular film.

HULLFISH: There have been a couple of movies I’ve talked to editors about where there was a hiatus — two of them because an actor broke an ankle during shooting — and that made huge changes to the movies because they had all those months. It makes you think that every movie should just take a year off.

YOON: It did feel like a gift — the gift of distance and perspective. One of the things that you’re always trying to do as an editor is to be an advocate for the audience and to have those fresh eyes and do that mental calculus of: What does this look like if I’m seeing it for the first time? What do I understand about the character and about the place in the plot? As you get towards the end of the editorial process the more impossible that is because you know everything that is missing, you know what gradations of performance and tone that you’ve left behind. You know what beats that there are and so you’re doing the best that you can to try and construct that objectivity intellectually, but you become less and less effective in doing that.

Having six months in the middle of this post gave us those fresh eyes again. There’s so much that you forget in that six month period. It would be interesting to see if you have that same experience in watching something years later. That’s something that I’m going to look for now as I rewatch my own movies months if not years later to see if new solutions to problems become obvious.

Having six months in the middle of this post gave us those fresh eyes again. There’s so much that you forget in that six month period. It would be interesting to see if you have that same experience in watching something years later. That’s something that I’m going to look for now as I rewatch my own movies months if not years later to see if new solutions to problems become obvious.

HULLFISH: I love the fact that you felt like you learned so much in the interim because you worked on First Man and learned the solutions that were used in that film. Thank you so much for this great interview. I really appreciate this.

YOON: My pleasure. Always great to talk with you.

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish

The first 50 interviews in the series provided the material for the book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV Editors.” This is a unique book that breaks down interviews with many of the world’s best editors and organizes it into a virtual roundtable discussion centering on the topics editors care about. It is a powerful tool for experienced and aspiring editors alike. Cinemontage and CinemaEditor magazine both gave it rave reviews. No other book provides the breadth of opinion and experience. Combined, the editors featured in the book have edited for over 1,000 years on many of the most iconic, critically acclaimed and biggest box office hits in the history of cinema.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now