Lee Smith, ACE, most recently cut the Bond flick, “Spectre” but has also cut “Master and Commander,” “Batman Begins,” “The Dark Knight,” and “Interstellar” and many others. He also has two Oscar nomination for Best Editing.

HULLFISH: There are a number of fight scenes in “Spectre.” What are some of your words of wisdom for approaching a fight scene?

spectre-Spectre_EPK_DOM_Clip_PalazzoExit_h264_hd from Steve Hullfish on Vimeo.

SMITH: Fight scenes kind of live and die on the quality of the fight coordinators and the ability of the actors to perform most of the fights themselves. If the stuntman or stuntwoman is heavily featured it can be a little bit tricky in terms of angle choice as the stunt performer has to be hidden from the audience, CGI has been used of late for head replacement, which is very useful but the physical movement of stunt person versus actor is quite often the giveaway making it difficult for the editor to hold onto a shot for any length of time. You have to follow who you’re with and make it as clear to the audience as possible at every given moment what’s going on. Some fight sequences end up getting cut to the point where you have no understanding of who’s fighting who or they might be lit in such a way that it’s difficult to figure out who’s fighting who and you have to slow the cut down just a little bit to make sure you’re with the main character. The fight has to have a narrative reason to be there rather than just people fighting. If there’s a cause and effect, you can follow it. If it’s just random explosions and people flying through the air and getting shot at, it gets boring very quickly. Indeed, fight sequences get boring very quickly if they’re not moving the story along. Just the visual excitement of it in some films is very tiring when the fight sequences just seem to go on too long.

HULLFISH: Do you find in those fight sequences if you have some kind of musical pacing: fast sections and pauses and changes in dynamics?

SMITH: Can be. You go into high speed photography (slow motion ) just to clarify a story point. Can be fun and very stylish. Or you can go for the visceral, realistic fight. You have to have the stakes sorted out. You have to have some reason for that action sequence to take place. Who’s stopping who and why are they stopping them and stay within some realms of plausible logic.

HULLFISH: I’m thinking about the sequence on the train between Bond and the giant guy. You mentioned the difficulties of editing when stunt people are involved. Bond flies through some walls and stuff like that, so I’m assuming a stunt person did at least some of that work.

spectre-Spectre_EPK_DOM_Clip_TrainFight_h264_hd from Steve Hullfish on Vimeo.

SMITH: That’s an interesting sequence. A lot of that, Daniel did himself and so did his nemesis, Mr. Hinx. That was a very physical sequence and Daniel actually got hurt and so did Hinx. They’re big, fit, tough guys and they weren’t pulling a lot of what they were doing. They are play fighting, but I stood next to both of them on occasion and you would not want to get hit by either one of them. The stunt guys were really only peppered throughout that scene in a very small fashion. The coverage was very weighted to the actors and that’s one of the reasons I think that sequence is so enjoyable to watch, because the percentage of stunt work is very small. You’re right that when you Bond got thrown through a wall backwards that the odds are it’s a stunt person and it was. But a lot of the time it was the actors who were ducking or taking punches. It was the real characters. It was all about how it was shot, where you cut, sometimes with the right angle you really can make it look like a punch connects. And in fact, in some instances, the punches DID connect. (laughs)

SMITH: That was all four single-camera set-ups that were all joined in the editing room and with the aid of digital technology, made seamless. Indeed it was just one camera. There were no choices in angles; just takes of the same camera set ups. That was how it had to be. We picked up the interior of the hotel in an edit, then Bond rides up in the lift and we pick up going in to the room in an edit, then after the Estrella’s dialogue on the bed we pick up an edit when the camera swings around and another edit as he steps out of the room onto the window ledge and along the rooftops. But for most people in the audience, it looks like a single shot. And indeed, a lot of my colleagues thought it was one take.

SMITH: Well, if you’ve got an editorial mind, and you clearly do, you can say, “I find it difficult to believe that you could have done that.” Sam Mendes wanted that sequence to work like that and it was very carefully orchestrated and very difficult to pull off. There were anomalies within those takes that had to be dealt with. We did little speed ramps to get things to go a bit quicker. There are probably 100 things that have been applied to that sequence aside from the edit points.

HULLFISH: What’s your approach to cutting a basic scene?

HULLFISH: I did the same on my last feature.

HULLFISH: What was the principle photography schedule?

SMITH: Six months. Starting in December going thru to June. Daniel got hurt in the train fight sequence, so we got delayed a bit while he recovered. Like a lot of films, you are thrown a couple of curve balls during the shoot. We were a bit weather-dependent and that eventually took its toll. I’d say there was another two weeks after principle photography was supposed to end with multiple units shooting the whole time.

SMITH: London. The whole show was based out of the UK.

HULLFISH: Pinewood?

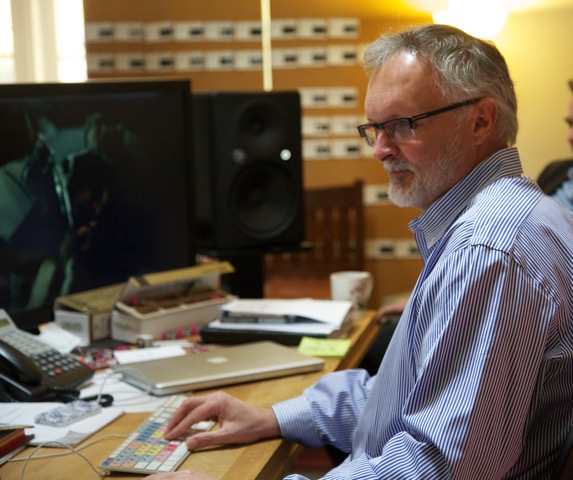

SMITH: Yeah. Pinewood, then we moved to SOHO for post. (John Lee, first assistant editor on the left, and Jeremy Richardson, assistant editor on the right.)

HULLFISH: I want to get back to your editing approach. It’s awesome that you consider it so easy and basic, but I want to dive a bit deeper. Do you use a selects reel, for instance or do you cut directly from the dailies?

spectre-Spectre_Clip_Hotel_Stereo_h264_hd from Steve Hullfish on Vimeo.

SMITH: Normally, for a straightforward scene I would just cut it straight from dailies. If it’s a complex action sequence, for example the helicopter doing all of the barrel-rolls, that sequence was shot over five days of principle photography and probably ten days of second unit – so maybe 100,000 feet just for that one scene. I would sit in a theater and pull selects while I was watching it. I’d be talking to my assistant, John Lee, and I’d be saying, “That’s a good take.” “That angle’s good.” “That camera’s good.” Then I’d pull a selects reel of all of the best moments. Just try and do a fast pass of just bolting it together because the only way you can actually see your way through these big, big sequences, it’s a good idea not to let them overwhelm you. Just do a slam cut where everything happens as it should happen in about the right time and don’t worry too much about jazzing it up. Just make it make sense and then go back, but you’ve at least got the structure, so you’ve built the house before you come in and do the fine sanding.

SMITH: Yeah. I think so. I remember very specifically on “The Dark Knight ” the scene where Batman interrogates the Joker and there were very specific moments in the body of that scene – and that had a lot of coverage and it was a big scene – but there were moments that were very striking and it’s a thing where it just prints into your brain in dailies and then you remember it as you’re editing and you think, “That wide shot where he gets launched across the table was incredibly shocking. So that’s what I want to use. I don’t want to overcut it. I want to stay in there.” And moments of performance that stick in your mind. I try to not overthink it. I’ve worked with editors over the years, not recently, but in the early days where they’d get stuck by continuously second-guessing and overthinking what they were doing and endlessly analyzing. I think a free-form edit often turns out better rather than sitting there worrying about every little thing that you can possibly worry about and finding that you obsess on one moment. I keep thinking of the film as an entire piece, not one section. You’ve got to run the movie as many times as you can fit in your schedule and we would normally run the movie at least once a week while we were in post, projected, because you can just get bogged down in a sequence and you realize that you’re applying too much time to something that’s unimportant and not enough time to something that’s very important.

HULLFISH: Meaning the overall structure of the film and seeing the scenes within the context of that structure?

PLEASE CLICK “NEXT” TO CONTINUE READING

HULLFISH: I was talking to Billy Fox about people who use selects reels a lot and he said, “Ah…you’re overthinking your choices. I don’t have to look at five takes of a guy saying a line back to back. I know what the right line is.”

HULLFISH: Let’s talk about performance for a bit. What catches your eye? Like that Joker scene. How much are you molding the performance and how much are you being a steward of the actors?

SMITH: I think it’s something that simply falls down to taste. You can’t second guess it. I always cut what I like. I don’t think about what anybody else likes. I had to do what I like. Because as soon as you think about “Well, what would the other person like?” you’re dead. Because now you’re no longer using your own in-built sense of rhythm and pacing and taste and when I was editing in the early days, I quite often would make that mistake and I’d be thinking, “Well, what’s the director going to like?” As an editor you’re obviously making the movie with the director and you’re pleasing the director. That’s critically important, especially with a good director. I have had the good fortune of working with some of the great directors and the simple nature of making the right decisions please them. But you don’t ever reverse engineer your thoughts. It’s the same thing with saying, “What would the audience like?” It’s a very dangerous game because if we all knew what the audience would like, it would be simple and every film would be a hit. You’ve got to try not to tailor your thoughts to anybody else’s thought pattern. Not the studio, not the director, not the producer… you’ve just got to be faithful and you’ll succeed or fail simply based upon that.

SMITH: On occasion, but if you’re working on a top level film with top level actors and a top level director, it’s rare. If you’re working with a lesser director then that can happen. Or if you’re working with a great director who has a very organic outlook and they’re not prepared to stick with something just because of what they’ve done before and they’re trying to push the envelope. It’s a fascinating thing and if there is something incorrect, it just jumps out at me, even before I play back for the director at the end of the shoot. I would have solved that problem or made the director aware of my concerns.

HULLFISH: Talk to me about how important sound design is in selling your cuts and making you feel like you’re delivering something that is going to get approved.

HULLFISH: I interviewed Mike Hill and Dan Handley about “Into the Sea” and they were talking about scenes with wave machines and wind machines and there’s no way to get useable sound. And they said that was very difficult to cut because of that. You can’t hear any dialogue at all.

SMITH: We had that on “Master and Commander” where we were shooting in the tank at Rosarito (Mexico). (http://www.bajafilmstudios.com/) where we shot all of the storm sequences. I the studio to build a small ADR studio while we were on location because in that instance there’s no way to use what was recorded, but we always pushed that it didn’t matter what the problem was, “Roll sound. It’s vital.” Because even if it’s the tiniest squeak of a noise, it gives us some direction and sync. I know we’re going to have to ADR, but pretend we’re not using ADR, and they did. At the same time, we’d steal the actors straight after that day and wheel them into our little ADR booth and get them to re record their dialogue because some of the original recordings were completely inaudible and the actors were kind of ad-libbing.

SMITH: Yes. I was so sound literate that I just couldn’t bear it. I was fixing the sound, cutting picture all at once and it just wasn’t working. Then as soon as I turned the sound off… it’s funny, your brain has to process a whole lot of information, and if you turn off the sound, there’s a whole lot of stuff you’re no longer thinking about. You can just build a very complicated sequence a lot quicker.

HULLFISH: Tell me about your sense of music. Several people have mentioned that they start listening to potential temp music as soon as they know they’re going to work on a picture.

SMITH: It’s really quite extraordinarily difficult (laughs) These guys are at the top of their game. I’ve worked with other great composers and some really young composers and all they’re missing is experience. Their talent is fantastic, but you’ve got to put the years on. This is an industry of experience and I think people get very excited about using someone who has never composed a feature film before and I say, “What have they done before?” Not to say that doesn’t work on occasion but experience buys you a guarantee .

SMITH: I think even with that moment with the Joker I wasn’t consciously saying “I had to get there.” It was more just in the back of my mind. There are moments that I like and in that initial assembly I find that the hard part of editing that I like to push through is the construction and the mechanics of the scene and you know when you have it kind of right. As for the entry, I don’t worry so much in the initial assembly of the scene because I don’t know what’s coming before or after since I’m editing as they’re shooting, don’t obsess about that because who knows when you want to go in to a super close up or whether you want to go wide on that first cut. That will come later when you have all the connecting parts. I believe in geography. I like to see the environment because then eye-lines all make sense. I do see films, where, for some reason, the editor has cut tight into a scene and then clearly had forgotten that they’d run 60 seconds of dialogue and the audience doesn’t know who’s looking at whom. Then they might cut out wide just because they fancied ending on a wide shot. But the whole problem for me is that it’s confusing because if there’re four people talking and they’re in a room and you’ve never set up that geography. I don’t want to say that there are any hard rules. There are times when that confusion might work to your advantage. Maybe that’s what you’re looking for, but I still like to get an understanding of the environment when I go in and then once I’m in I don’t particularly like going back out again. I always say to the guys I work with, “You’ve got to have a reason to cut. Don’t just cut.” Anyone can do that. You sit there and you’re bored, so you cut. You’re bored, so you cut. It’s terrible. It’s not a good reason. You cut for dramatic reasons. You cut to shift emphasis. You cut for a reaction that’s stronger than a line. That’s how you cut in my opinion.

SMITH: But that illustrates the point. You were cutting for a reason. And I just did a scene on a film where I’m I cut back to the wide shot in the middle of the scene too, to show the danger of the environment. As you just said, you cut to the wide to show two characters who’ve come to a pause in their dialog and rather than cut to two singles, you cut wide. There’s reason. But that’s the thing. There has to be a reason.

HULLFISH: Do you find in the grammar or the syntax of editing that you are trying to build to a close-up on a specific moment? Someone showed me a cut to a big close-up instantly and for what I thought was a rather mundane moment.

HULLFISH: With that many coverage options, I spoke to someone else that said they try to never go back to the same shot, or never repeat themselves. Do you feel that necessity? I feel like, if I’ve got a great close-up, I can cut to that as many times as I need to.

PLEASE CLICK “NEXT” BELOW TO CONTINUE READING

SMITH: Yeah, yeah. It doesn’t matter if that ruins the rhythm of your cut or ruins the fact that you can’t get where you want to go. Take the hit and stay with the reason that you’re looking at them. Maybe you’ve got a third character listening to a scene and you realize that you’ve gone to all this trouble to put this shot of that person listening, but not one moment in the scene do they require that shot. There’s nothing about that shot that’s moving the story forward and they’re not important enough to cut to. I’ve seen these cuts where the editor feels like they want to be inclusive and they want to join everyone into the fray, but you realize that they’ve put a very important piece of dialogue over a secondary character and it’s like, “Why?” If they’re not doing anything, don’t cut to them.

SMITH: Once you see that first run you quickly see where it lags and where it slows down. The other thing you might realize is that where something seemed very clear in the script, on film it’s no longer clear, the scene has come too far away from the event. It’s cause and effect. You’ve set something up, but you’ve waited 20 minutes to show it and in that 20 minutes or 10 minutes or 8 minutes or 4 minutes, you’ve kind of forgotten what it was that you were shown. You feel that. Then you’ve got the process of figuring out if maybe there’s a scene that’s a “floater.” Can we drag that scene out and put it somewhere else so we can get the cause closer to the effect? That is a lot of what you do is structurally move things around, whereas in script form it just wasn’t that noticeable, but in the flow of the film you realize that you’ve talked about a character or you’ve talked about an event, but you’ve waited too long and by the time you get into that scene you’re confused. Yet, it’s exactly as it should be, just too far apart or there’s too much complexity between the two thoughts. Then you go through the process of re-engineering and some films I’ve re-engineered massively, like the whole third act becomes the second act. Or the whole last part of the third act becomes the beginning. Films that you look at that are confusing and don’t work, you have to employ some fairly large thinking. It’s no time for little ideas. You’ve got to start thinking big and try big. Try something that was never in the script.

HULLFISH: Lee, can you walk us through your thoughts on cutting this sequence?

spectre-Spectre_EPK_DOM_Clip_PalazzoExit_h264_hd from Steve Hullfish on Vimeo.

HULLFISH: Thank you so much for sharing your thoughts on the art and craft of editing with us. It was a fascinating look into your process.

SMITH:

Thanks is was a pleasure talking with you!

If you are interested in reading the other two dozen interviews in this series, use THIS LINK. For updates on future interviews and my take on the world of post-production, follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish