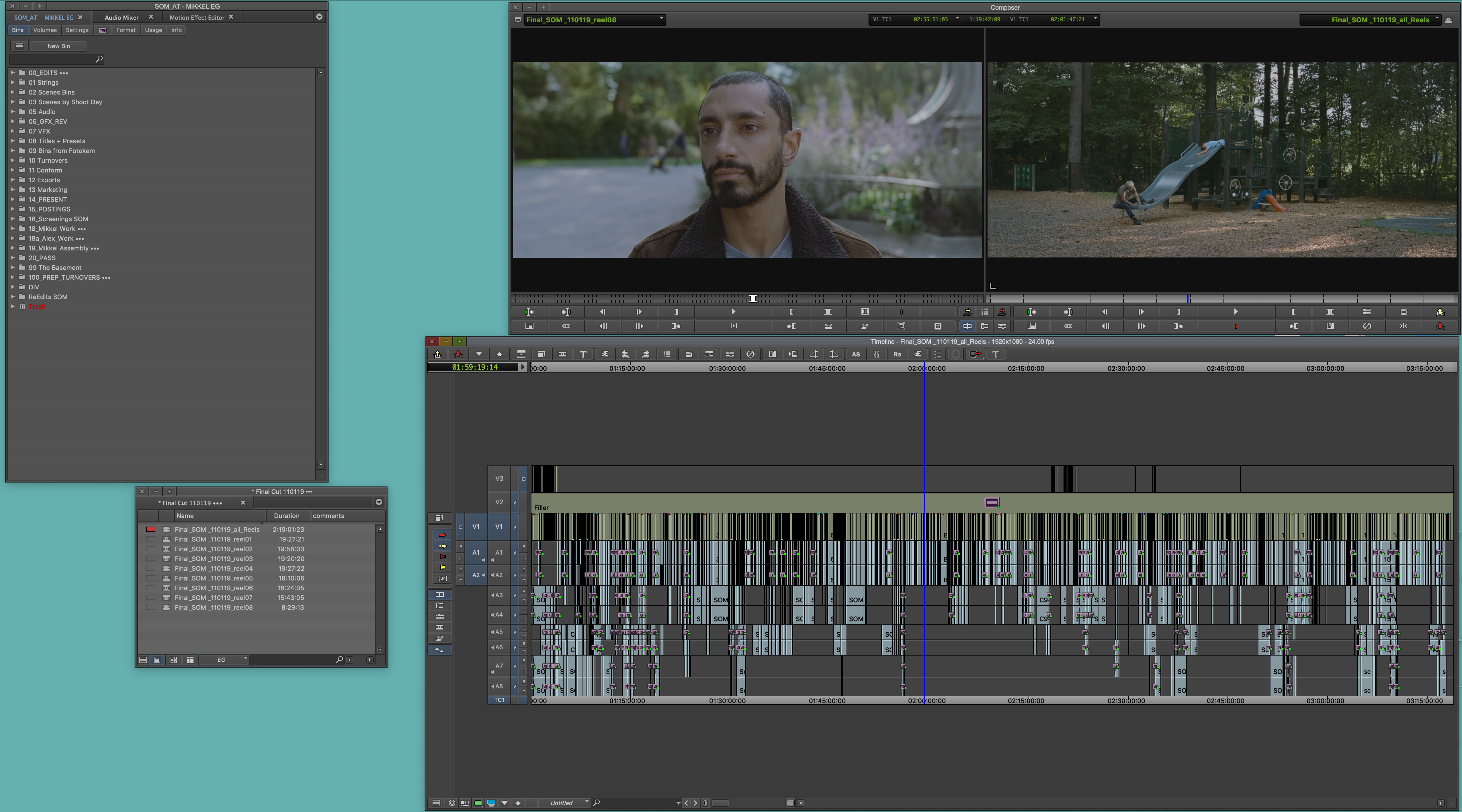

Today’s interview is with Mikkel E.G. Nielsen. We talked via Zoom with him at his home in Copenhagen, Denmark, and me in Chicago. We talked about his editing on the film Sound of Metal for director, Darius Marder.

Mikkel’s accomplishments include multiple Danish Film awards for editing and back to back wins in 2004 and 2005

His filmography includes Beasts of No Nation, a Royal Affair, King’s Game, and Madame Bovary.

Mikkel regularly jets back and forth between Copenhagen and either New York or LA to cut spots for Rock Paper Scissors.

This interview is available as a podcast.

(This interview was transcribed with SpeedScriber. Thanks to Martin Baker at Digital Heaven)

HULLFISH

It’s a pleasure to meet you. Tell me a little bit about working for Rock Paper Scissors and how your career has gone did you start in spots and move into features or the other way around?

NIELSEN

No, I started editing news on TV.

HULLFISH

Me too.

NIELSEN

I was the sound guy in the field and then I would edit it. Denmark is such a small country so you kind of have to go to film school in order to get to edit a feature film.

The way to get into editing was that in high school my class was in this film by a Danish director and I had some lines with all my friends and I really looked forward to seeing the film. Then when we sat in that cinema all my friends were there, but I was absolutely nowhere. So that was the reveal of the edit.

OK. Someone picks and chooses. And then I went to film school in Copenhagen which was in 97 and from then on I started on my first feature like the day after I finished film school.

HULLFISH

Wow.

NIELSEN

So I was lucky. I was just lucky to be asked.

You do a graduation film so you work closely for four years at the Danish film school, only editing for four years — six students in the editing program. There are DPs and producers and directors and those people work closely and in small groups and you do one midterm film. You do a lot of short films that can only be shown internally, but then you do one graduation film that you can show out to the world.

So you get an edit room and you get a lot of other students that edit the same scenes or with the same material. You see with six different eyes and a teacher or a director coming in. That was super interesting.

From then on I went on doing feature films. But the thing is in such a small country, you have the possibility of working in all fields — music videos, documentaries, commercials, feature films, TV shows. So it’s fun to try all different things. But I wanted to do feature films at that time so I was lucky enough to be able to work with a lot of different Danish directors and Swedish directors.

Then I think in 2012 I was approached by Rock Paper Scissors to work on commercials as well from the US and I’ve been there ever since.

HULLFISH

And you commute back and forth to do that?

NIELSEN

Yeah I lived in New York in 12 and I have a place in New York, but my wife and kids went back because she’s a mediator so she had to go back and work, and then we found out that it actually worked out pretty well to commute back and forth and it’s almost like two weeks a month in New York or L.A. It depends on the job. So we have offices in L.A. and New York.

HULLFISH

Let’s talk about Sound of Metal. How did that project come about for you?

NIELSEN

I was approached about three weeks before they finished shooting. Darius had been looking for an editor for a very long time. The company producing the film, Caviar, and they mostly work in Europe. The founder and the producer who produced this movie are French or Belgian, so I think they somehow probably put me on the list of potential people who could do this.

I think Darius talked to a lot of different editors and I had a call with him. We discussed how he likes to work — because he used to be an editor himself. He came from documentaries.

This film is based on the documentary by Derek Cianfrance that Darius was editing, which was about this band Jucifer, where one of them loses his hearing and then they couldn’t finish it. I don’t know I’ve never seen it. I just know that somehow Darius took over this baby many, many years ago trying to develop this film. Got obsessed with the whole idea that you have to go into the head of the character and see and hear from this character’s perspective.

Then we just had this conversation how he thought it should be and I told him how I wanted it to be because it was a very personal project for him. He spent so many years trying to raise this and it was very dear to him. You could feel that immediately.

I also saw rushes, so I could feel that there’s something really interesting in the material — at least from my perspective. I also told him how I would like to work If we go on this journey together and apparently it worked.

He told me I was the first one who told him how I wanted to do it and that’s what he was looking for. So I asked him to just give me all the material and not talk too much about it. And then I would start from scratch doing an assembly of my own and show him a first assembly.

HULLFISH

So it sounds like the film had already been shot when you came on or part of it had already been shot.

NIELSEN

They were in Europe shooting the last part of the film. They shot it chronologically, so I think they had a couple of weeks of shooting left.

HULLFISH

Talk to me a little bit about sound design. Obviously, the sound design was so important to the film. How important was it for you to have some sense of the sound design while you were doing the picture cut?

NIELSEN

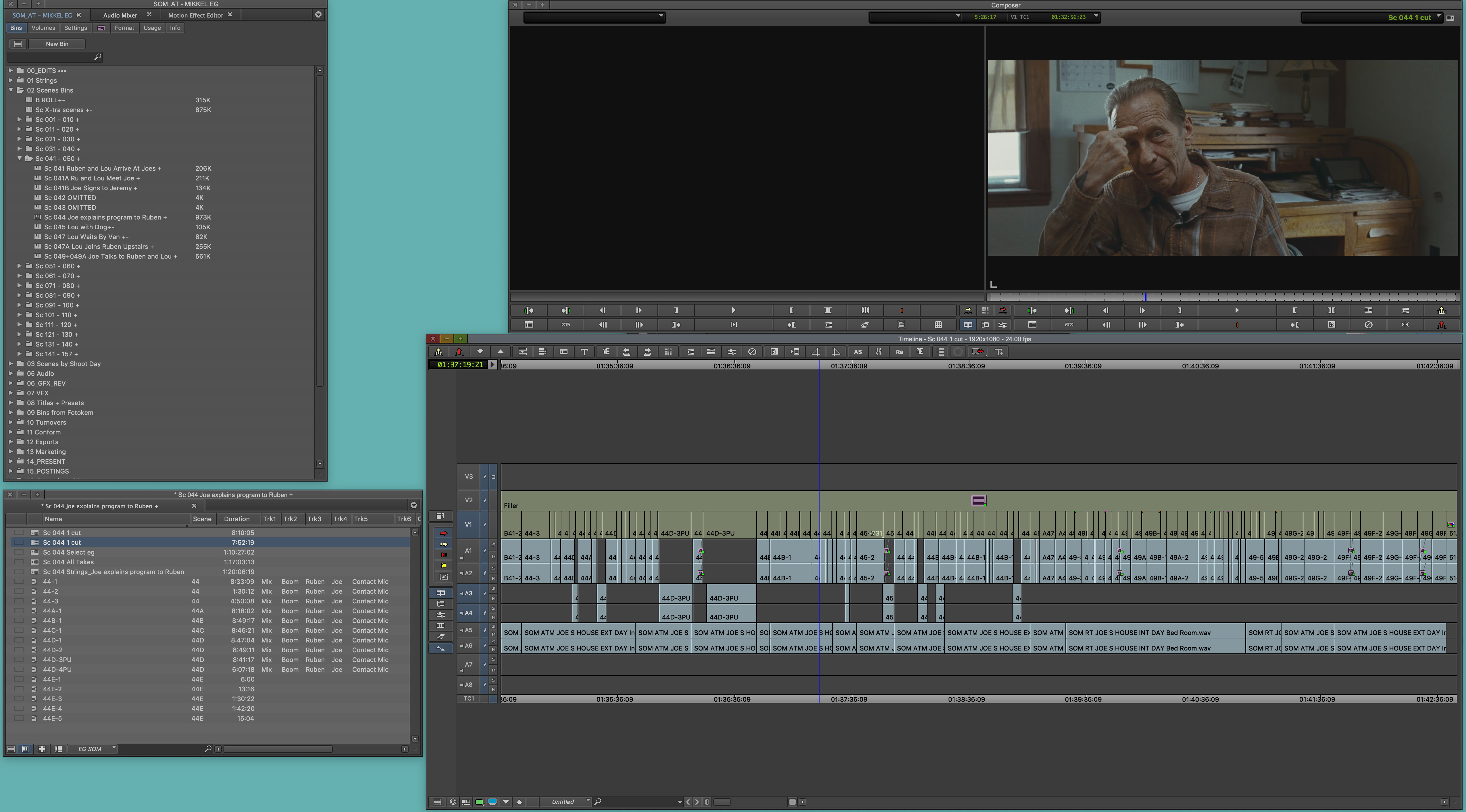

Nicolas Becker was the sound designer. He had worked closely with Darius about what it should sound like or at least how it could potentially sound or what it sounds like from an internal sound.

But I was more interested in it from a story perspective. When do you go in and out? When does it become too tiring? How long can you stay in that world? I got a lot of atmospheres from Nicolas. I tried to limit myself to only work with eight audio tracks so the dialog in mono, and then you would have the atmosphere stereo to broaden it out, and then I would play around with filters and drones to create the tinnitus sound to just have the sense and feeling of when to go in or out of Ruben’s head.

Also, together with Nicolas, we would send Darius scenes and he would look at them. It’s a very interesting collaboration because Darius was super open from the moment that he sent that material and saw everything even though he’d been working on the script for so long, he said, “Let’s just play around with the material. This is fun. This is a dream project for me. So let’s go all the way.” Which is super interesting as an editor just to be able to approach the material like, “What if we do it like this, this, and this? And what would happen if we try this?” At least to know we’ve tried it and this is right or wrong for the project.

And then, to your point about sound design, from the moment Ruben gets his cochlear implants, Nicholas had given me a program called IRCAN which is some sort of equalizer program that you run everything through. So I would export the whole ending and run it through this program and that would filter it so it sounded like this digital noise.

I would watch everything with that and then I could go in and out and see when do we want to be inside of his head and when do we want to be outside? How long can you actually stay in that insane digital sound?

HULLFISH

And there are other places before you get to that point in the movie where you’re also trying to decide: are you in his head or not in his head?

So much of it’s from his perspective, correct?

I’d really be interested in hearing more about that initial interview when you told the director about what YOU wanted the movie to be like. Because that sounds like a very dangerous thing to do with a project that the director is so passionate about.

NIELSEN

I didn’t say anything to him to that point. He mentioned all these things that he wanted to achieve. To be honest, I felt that if we could achieve like 60 or 70 percent of his vision, it would be amazing. But I doubted it because it’s a lot to ask for. Also as a first-time director, he was challenging the story to the extreme — which I like.

I find that attractive. I’m willing to go all the way in that sense, with him. For example, he wanted it to be closed-captioned. He wanted it to be an experience where a deaf person — for the first time — would be able see this film, and we, as hearing people, would be excluded and see it as deaf people would normally see a normal film.

So, he wanted it to be closed-caption. That was from the start. And we had to work with that. And then he wanted it to go into this internal sound. He didn’t want us to subtitle all the sign language. This was a dialog between Darius and me, of course, but we felt that if you go on a journey with your main character, you can never know more than your main character.

We have to know as little as he knows. And if we enter a deaf community we have to see the world just the way he sees it. So we are just completely not sure what’s going on up to the midpoint of the film. That’s at the one-hour mark, where Ruben is on a slide with a boy and suddenly you awaken the senses in Ruben again….

HULLFISH

And then there’s a little montage after that.

NIELSEN

Right. That montage feels like something changes with Ruben in that scene.

HULLFISH

There’s the noise of the wind.

NIELSEN

Yeah. Time is passing and the next time you see him, everything is subtitled and he speaks sign-language. You have already seen him try and open up to this community, and from then on, he is ahead of you all the way.

He suddenly has a project. He has this whole thing about starting to sell things from his Airstream, and you wonder what’s going on. What is this guy doing? Then you realize that he’s still on this journey to get his cochlear implants. So that’s the midpoint.

We felt that that’s how it has to be. It has to be earned — that moment.

HULLFISH

It has to be earned. Exactly.

NIELSEN

It has to be earned and it has to feel real that you stay with Ruben in that community. Because we played a lot with the montages and every time it felt like it doesn’t feel right. Something’s wrong.

We can’t suddenly go into a normal montage where you would put music or drumming.

There’s a piano scene where we see the kids hanging on. We played for a very long time with that scene to open up after the slide. That piano would open up into a long montage and it felt really nice in the moment watching a montage, but every time it just felt “it’s not real.”.

HULLFISH

I was struck by the moments that you chose to go “in and out of his head.” I’m just gonna preface this by saying that I’m not criticizing it in any way I’m interested in having a dialogue with you, of course. I loved the movie and I thought the editing was sensational.

NIELSEN

Thank you.

HULLFISH

One of the places that I thought was really interesting where you chose to NOT be in his head is a scene where he’s brushing his teeth. The audience hears it in a normal manner. But that could be completely internal to him — this moment where he’s not speaking, he’s not doing anything.

Or there’s another moment where his girlfriend gets in a cab and after she leaves again we’re not in his head in a place where we’re completely with him, you’re actually hearing normal sounds, so I’m really interested in hearing how you made those decisions of when to be in and out of his head.

NIELSEN

First of all, it’s very important how to get into his head. It’s all about awaking the senses. And it’s a very “under-told” story. Normally you would definitely start by telling the issues. A lot of things you have to figure out yourself with this film. And it wasn’t until the moment when we figured out that first act — those first ten minutes — those were difficult, because it had to, first of all, be about this couple that is equal on stage but also has a love relationship. So you have to understand the relationship between them.

But it was very late in the process that the concert became the start because that concert — that first image of him sitting there and then sitting in the end? It made a whole. And it made sense because we wanted to create a world where you awaken your senses. You don’t know what’s going on.

For some people, the kind of music that we start the movie with is horrifying or way too aggressive. It kind of gets you on the edge of your seat. Then you go into this very silent opening of an Airstream — him sleeping, then he makes a smoothie, which is a loud noise and then you see him using compressed air to clean his mixer, then he puts on a record.

So you just awaken the senses by hearing those loud noises and quiet noises, but also visually with your eyes. You have to look at the details in these things. And then when we got to that point where he says, “Soundcheck,” that’s the last word before he loses his hearing.

Then you go into this world of him losing. You feel that you’re going with him. There’s a small tinnitus sound and this drone which we worked a lot with. Obviously, the sound people have done amazing work afterward, but it’s still the same feeling. It could just be muted anyhow. Then you would still feel that something’s happening and you react the same way with your character.

Then it’s about how long can you stay in that world, and when do you want to go in or out of that world with your character, because there are also some things that we need to understand. We need to understand how big of a loss this is. By showing the scene in the pharmacy extremely muffled then there are maybe two or three places where we jump out and you just hear the words as normal sound and you see that desperation from your main character, Ruben, and it’s like a horror movie. If I experienced that myself it would be completely terrifying.

Then, of course, you play around with that internal-external sound and you make him also making stupid decisions like with the audiologist saying “you have to be cautious” then you cut to him at the drum kit, then you know what kind of person he is.

The first moment you see him he has a big tattoo “Please kill me” on his chest. There were a lot of extra scenes where we discussed: What kind of band are they? How successful are they? How much do we have to go into the fact that he can’t hear? Does Lou (his girlfriend) know that he can’t hear?

Little by little you peel these things off and you find your character by saying, “We have to stay with him.” It’s all about if we stay with the Ruben and if we feel Ruben all the time, I at least felt, “We’re home safe” in the sense that we have developed the language where I, as an audience, follow this guy through a strange experience that maybe I can’t hear or see or anything, but at least I know that it’s taking me through this journey somehow. That was at least the plan.

HULLFISH

I definitely felt that.

You mentioned that you didn’t want to explain things like when he first goes to this house where he’s learning sign language they’re doing sign language and they don’t explain what they’re saying because Ruben doesn’t understand it, right? So the audience is right there with him. You’re frustrated because you don’t know what’s going on and you’re frustrated for him. Yeah, I thought it was lovely.

NIELSEN

Darius and I had a screening in Toronto and that was the first time with a huge audience and there were so many deaf people watching the film and it was amazing for us because suddenly they started laughing and the rest of us thought, “What’s going on?”

HULLFISH

There’s a big deaf school just south of Toronto in Rochester.

NIELSEN

It was super interesting.

HULLFISH

I’m really intrigued by what you were saying about kind of peeling the scenes back. Can you describe how the film started originally and then got to the point where you’re starting with him sitting at that drum set? How did the film start when you did your editors cut?

NIELSEN

The way I work is that I screen footage for the first two or three weeks — just screen footage and select and mark it and put it after each other. Then after a couple of weeks, I kind of find the material’s rhythm and the character’s rhythm. You understand how the DP breathes with the director. Every film has its own rhythm.

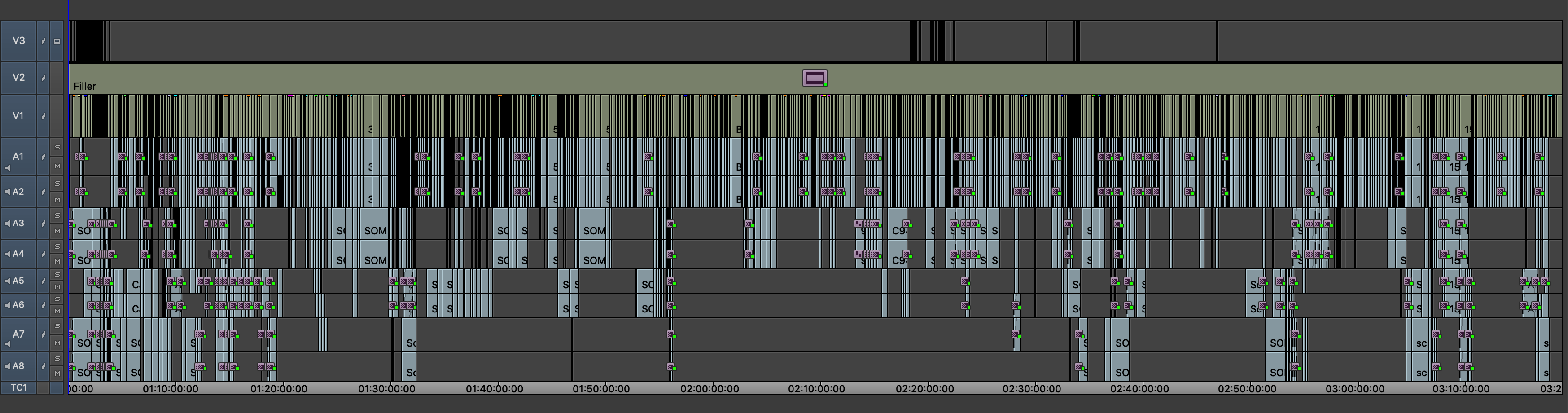

Then it’s easy suddenly to do a first pass. My first pass was maybe three hours and 45 minutes. And I probably put that together in two weeks from selecting all the scenes and then I showed it to Darius.

The opening scene was actually after the concert — the Airstream. Ruben wakes up in the Airstream. Then there would be a lot of technical stuff. Ruben would wake up Lou and she would talk about music. It was to help you find the relationship. But it was difficult to understand: Are they equal? What level are they are? We had a scene with a leaf blower out in the front that would somehow irritate him and he went out aggressively and shouted at the guy with the leaf blower, which reads right and it looks right and sounds right, but it’s about awakening the senses.

The moment we moved that concert up to the beginning of the film, you immediately know afterward — when you see the two of them — they’re equal. She was the singer. He was the drummer. They’re the band. They’re a unit.

The way he wakes her up and makes her a smoothie. He wakes her up very pleasantly — very nice. Then they start dancing. Then they go on tour in a montage until you get to a concert and then suddenly he loses his hearing which was very appealing because it was doing all the right things up to that point where you suddenly know Ruben.

It’s not so much about the things you are seeing, it’s about who are they as people. And you also like Lou a lot.

HULLFISH

They’re definitely both likable. Correct me if I’m wrong — before he loses his hearing in the concert there are moments where he panics because SOMETHING happens to his hearing — He’s trying to clear his ears or he feels like he’s underwater?

NIELSEN

You go on tour with them in the Airstream and you have fun, short dialogue and then they are putting up the merchandise with another band and they talk about T-shirts and records and stuff like that, and then he says “Soundcheck” and that’s where he loses his hearing. It’s a different language but it works.

It’s not the normal shot that you would use as an internal sound with Ruben, but it works in the sense that you understand that he’s still trying to do his concert but everything is strange for him and then he wakes up in the Airstream and everything’s muffled — standing in the shower you can’t hear the drops and he’s also in front of the mirror.

Then he goes to the pharmacy and then to the doctor. It’s natural — like what would you do? It’s a problem we solve — or at least we try and solve it and then we go to a concert. He’s a fixer. He’s trying to fix it.

HULLFISH

There are lots of little moments at the deaf school that felt very documentary. How much other stuff — other moments — were there to select from?

You said your first assembly was three hours plus what was your guiding principle in choosing what to keep and what to eliminate?

NIELSEN

There was a lot of really really nice material at the deaf school, but somehow it felt like we had to stay with Ruben’s journey all the way. It makes sense to introduce characters but it shouldn’t be that the teacher and he fall in love. It would be a different story. Even though there are small hints — a lot of people would think, “Hey, here’s the new girl” and they’re super nice together, but it’s not that kind of film.

It’s very important that Rubin is a likable character. He enters a world and they open up and they invite him in. So it was all about the journey for this guy. And less is more sometimes.

When we found out the way Joe works — the guy who runs the deaf house, and those dialog scenes between the two of them. It was so refreshing. Or where they would all sit around and you see that they’re all addicts. Or how there’s a board with assignments for everyone and having fun — even though it’s really slow, in a sense — but it’s also trying to move forward.

It’s always going on the emotion, hopefully, at least that’s what we tried with Darius. Then we had these small tricks to go in and out of his world which can sometimes be very emotional.

Like when he invites that kid out to the playground during the school presentation — because why, if you can’t hear anything, could you just sit still. So he knows and he invites this kid out and then suddenly he finds that world again — drumming — the vibration. It opens up a world for him. And from then on he’s a part of that whole community.

HULLFISH

One of the shots that I loved was when he’s told to go into this room to write his feelings. He opens up this door to what is just a very simple small room with a table and a chair and the look on his face is as if it’s a horror film and there’s a ghost or a monster in there. Spectacular.

NIELSEN

Yeah because Ruben’s problem is he can’t sit still. And he sees that from the opening shot in the movie. I like that scene.

I gave it that scene to the students at the film school. It’s interesting to see how different eyes look at the same material. It’s also about who you are as a person. How you put these things together? It’s very rewarding to see other people do the same and talk about it.

HULLFISH

I’ve done a film class once where we got 20 or 30 experienced editors and we all cut the exact same scene and to see multiple people cut the same scene is really revealing and interesting.

NIELSEN

It’s so interesting why something works in one version and it doesn’t work or someone starts on the right image and suddenly it’s a completely different scene or status in a dialogue scene — if you just take out one word or you move one word up from the front to the end and suddenly everything completely changes and you see the characters with completely different eyes. It’s really interesting what it can do.

I would call it a fun challenge because Darius shot dialogue scenes where one is deaf and doesn’t understand sign language and the other one — that early scene where Joe is trying to talk to Ruben using a computer that transcribes spoken words and displays them in real-time on the screen. You have three characters in that scene — Joe, Ruben and you have the monitor. And to understand that every time Ruben looks to the left he is reading. And it has to feel right.

You would normally cut to that character — the monitor — but it would take ages if he had to read all these lines every time someone said it. The next challenge was: do we actually have to stay out in wider shots? Can we go into close-ups? Because do we need to see the screen all the time. So how does that work? So it’s super interesting to edit these scenes. It was a fun, fun, fun, challenge.

When do they do what, and how does it change? Like suddenly we introduce addiction 50 minutes into the film maybe you felt it but you’ve never talked about it. So it suddenly becomes about something completely different.

I thought it was about losing your hearing but no now it’s about addiction.

HULLFISH

Because the film is so deeply in Ruben’s perspective, the times that you choose to come out of his perspective are important. And one of the places I thought of was in an early diner scene with Lou and Ruben.

You’ve been pretty much in his head — how frustrated he is that he can’t hear — but then there’s a moment where you cut to her looking at him very concerned.

NIELSEN

It’s all about how you feel it when you watch it. Does it work? If it works, it works, right? And if it doesn’t work we have to fix it somehow. But it’s also about — we have to remember — me and you and everyone else, as an audience — that even though he’s talking, talking, talking, he is still not listening.

At Joe’s house, they are in the Airstream at night and Ruben wants to go back on tour and he’s saying he’ll fix it, then he’s hugging and giving her a kiss. And you cut to the side shot and you suddenly reveal that drone or that anxiety which is within him. And you remember: this is what’s going on with Ruben — we cut directly to him trashing the Airstream and she wakes up she can’t understand what’s going on with him. He’s losing it.

Then suddenly she’s leaving and there are so many small things that you’re not really told what’s going on, but emotionally it feels earned and right because Ruben has absolutely no idea who’s calling and why she’s leaving suddenly there’s a taxi and she’s just gone and you stay on a wide shot for a very long time and you hear a distant train.

HULLFISH

You’re switching back and forth between cutting feature films and cutting spots. Is it a different muscle? Are you exercising different skills or do you feel like you’re always exercising the same skill?

NIELSEN

It’s the same skill but I would say that it’s probably the opposite of directors because sometimes I go to commercials or music videos and stuff like that to stay sane.

You could call it method editing somehow because it’s all about you go so deep into the world of your main character with him. And personally, I could go on a silent retreat just to try and feel how does it feel to not listen for a long time.

To really understand, I connected with this character because I am a drummer myself. I’ve been drumming all my life. I’ve always had a drum kit in my edit room. I could completely understand losing a sense. That would be terrible. I would absolutely hate losing my sense of hearing.

And then you ask yourself, What would you rather lose? The eyes or the ears? I don’t want to lose any of them but probably I would lose the eyes. At least then I would still have music and sounds and dialogue. It would be easier to navigate, probably, with only your hearing.

HULLFISH

Did you mention to the director that you were a drummer when you had your interview?

NIELSEN

Yeah. I told him I connected with the material. He said, “That’s amazing. That’s good.” I also grew up in a commune home and my father is a musician and he’s been a musician for 50 years, and he’s also losing his hearing.

HULLFISH

My dad is a musician who’s losing his hearing.

NIELSEN

For me, it wasn’t about the addiction, but then my addiction would then be that I work way too much. I like to work.

You asked about cutting spots and feature films. I think that it’s very important that we challenge ourselves all the time and doing spots and meeting new directors.

It’s a long time to sit in an edit room for six-nine months, right? I absolutely love it. But it’s also the journey with that with those people you are in the room with. It’s super interesting to get to meet and to understand what a director dreams about and wants to do, right?

They put their little baby in your hands and then you try to mold it and then suddenly you have to protect it from them because they get tired.

I just find it interesting to go back and forth and do projects sometimes of three weeks, four weeks for a spot, and also you get to try and work with multiple DPs v and amazing directors as well. So for me, it’s super challenging.

HULLFISH

Is it different to cut when a film’s been primarily shot? Usually, you’re getting the material where you have to work with it out of context. Scene 42 is the first scene your cutting maybe, then scene 12, On this movie, you could have cut in order, correct?

NIELSEN

I did. I would screen footage and do the selects, but then sometimes it gets a little boring to stay in that world and then you go to something else because screening and screening and screening and getting into that material is sometimes tiring.

And I don’t really see it. It’s mechanical. You put together a scene. But a dialogue scene is a dialogue scene. You try to put it together as fast as possible, from my perspective, and then find the characters and find the story.

For me, it’s interesting to put everything together fast and see what is it we have. And from then on you start playing with other things. I can easily start already taking out things that I don’t like or think that could work potentially in a better way, but I think it would be wrong to do that or at least I would probably do it on the side and have it as a backup because sometimes something interesting happens when you put together a first assembly just out of your instincts.

And sometimes I put things together wrong compared to what the vision was from the director, but wrong doesn’t mean that it’s not right in the sense that it might be the way it ends up.

You’ve talked to so many different editors and you know that sometimes when you polish everything and it gets smooth and nice and you’re almost done with the final cut, then you go back and you see the first assembly and you see some amazing moment.

You’ve talked to so many different editors and you know that sometimes when you polish everything and it gets smooth and nice and you’re almost done with the final cut, then you go back and you see the first assembly and you see some amazing moment.

“What if we just put this in here?” Or sometimes the first assembly of a scene makes it to the final movie because that moment when the material meets your eyes and something magical sometimes can happen.

HULLFISH

What happens when you cut a scene and realize it’s not right and that you have to start over?

NIELSEN

There’s no right or wrong in the editing room. Any stupid idea is allowed — at least it should be allowed and it should be a safe area. It should be a safe area for the director, for me, for the producer, for the actor, for anyone to say what if we did it like this and they would say, “It’s terrible. Look, it’s completely wrong.”

Yes, but at least then we know that this path doesn’t work.

With this film, for example, it was just this feeling that we are connecting with our characters.

Like that early scene where he’s waking her up with the drumstick on her arm and you see small things like she has cut her arm and that connects to something done in the last act where she suddenly started to scratch it again and you feel this is part of Ruben and Lou.

HULLFISH

I love starting on him drumming because it’s your sole way of knowing who he is. And then when he loses his hearing you know that you’re losing the thing that defines him. And if you started out with him “as a person.” By starting out on him at that drum kit, you’re stating, “His life is sitting at this drum set and if he can’t hear…”.

NIELSEN

Also, it’s an interesting scene to start with because the DP and Darius wanted to shoot the scene without cutaways. The actors knew how to play and sing. There are no cutaways, there’s no actual drummer sitting in. He had to learn to play drums to play that scene, otherwise, he’s not Ruben.

He had to learn sign language to play that role. That’s what Darius was asking for from his actor. Therefore as an editor, you feel like you would go a ton of extra miles for him because he’s already asked so many people to do this.

He’s already spent almost ten years of his own life to try and do this film, so why wouldn’t I go that extra mile to try and turn those small stones and see what if?

What would happen if we did this and this and this?

Also, we had the possibility to re-edit the film after they did the final mix because they did sound for so long. And it opened our eyes to be a little more precise, especially at the deaf community — that part.

For a very long time, we had montages from being on that playground slide to when he knows sign language.

Then, at a point after action after the Toronto screening, we had the possibility of taking out maybe 10-15 minutes of the film.

HULLFISH

Did you?

NIELSEN

Yeah. I mean that’s a gift. Who gets to re-edit things and see them with fresh eyes and you’ve seen how some people react to something. It’s just about being as precise as possible in what you’re trying to achieve or tell.

And it would also be, to be honest to the material and to the characters and to the story and Darius. That way it’s been a fantastic project to work on.

An interesting thing is that there are only two pieces of music in the film.

HULLFISH

And why do you think that is? What was the decision making behind that?

NIELSEN

There’s the concert up in the start and then there’s a piano piece in the end but then there’s also a piano piece in the middle, but those are earned pieces because they’re in in the scenes.

We work with emotions. It’s not music in the sense of a score. It’s small in the sense of a personal journey. And that was a key to finding the film cause we were struggling a lot from that diner scene when they’re going to Joe’s place for the first time. Should that be a music piece? They’re moving from one state to another state. It’s day and night and you had a montage of things, but it’s the first time you have a montage of inner emotions. How he’s hearing the sounds of the RV driving — the atmosphere outside. So you traveled with him through that whole emotional journey up to that point and that’s how we kind of envisioned or wanted to play with music as an emotional journey or emotional piece. It’s the same as the small piece that you don’t really recognize would do or a drone or something that opens up or goes down.

It’s not like specific score music but it’s more like emotions.

HULLFISH

I was going to ask you about that montage of traveling to the deaf community. What was the value of the “shoe leather?” What was the value of the travel time especially with no real music underneath there?

NIELSEN

First of all, you don’t really know where they’re going, so you needed to take those words in and move yourself because you’re trying to figure out what is it about. So for us to go there — and she already told us it’s gonna take us a couple of days — if you just cut to the scene where the sign says, “deaf children playing” It wouldn’t be earned. You wouldn’t have that feeling that this is Ruben’s journey,

So therefore it has to be Ruben’s journey. He doesn’t know what he’s getting into. He doesn’t know what’s happening. He doesn’t know what he’s going into, but he finds out. Right? With us.

We don’t know what we’re going into. We don’t know who the guy is? What it’s all about? It’s an internal montage to move him from one place to the other.

HULLFISH

HULLFISH

Thank you very much for talking to us about this. It’s a really beautiful film. Very emotional. Thank you for cutting it.

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish or on imdb.

The first 50 interviews in the series provided the material for the book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV Editors.” This is a unique book that breaks down interviews with many of the world’s best editors and organizes it into a virtual roundtable discussion centering on the topics editors care about. It is a powerful tool for experienced and aspiring editors alike. Cinemontage and CinemaEditor magazine both gave it rave reviews. No other book provides the breadth of opinion and experience. Combined, the editors featured in the book have edited for over 1,000 years on many of the most iconic, critically acclaimed, and biggest box office hits in the history of cinema.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now