Art of the Cut is brought to you by our friends at Frame.io.Video collaboration for the 21st century Read all of the AOTC interviews or learn more about Frame.io |

Each of my three previous interviews with Eddie Hamilton, ACE have been epic master classes in editing from a guy who loves talking about his craft and sharing with his colleagues in the industry. We talked to Eddie about the last Mission: Impossible movie, and also for the first Kingsman movie and the follow-up: Kingsman: The Golden Circle.

In addition to these movies, Eddie’s also cut Kick-Ass, Kick-Ass 2 and X-Men: First Class, working side-by-side with some of the best editors in the business. In this edition of Art of the Cut, we talk about Mission: Impossible – Fallout. Be careful! You may be tempted to use your yellow highlighter on many of the pearls of wisdom within, but remember: you’re reading it on your computer…or some other screen-based device. There’s a lot to digest here and this is a really media-rich article, so you may want to bookmark this and come back several times.

(This interview was transcribed with SpeedScriber. Thanks to Martin Baker at Digital Heaven)

HULLFISH: Tell me a little bit about the schedule on this one.

HAMILTON: The crew started filming at the start of April 2017 while I was still finishing Kingsman: The Golden Circle. So for the first eight weeks, when they were filming in Paris, I was doing days on Golden Circle and evenings and weekends on Mission: Impossible. We were sound mixing and color correcting and doing VFX reviews on Golden Circle.

Full credit to my editorial team who followed me onto Mission, I couldn’t have survived without their daily hard work and good humour. Drumroll for First Assistants Riccardo Bacigalupo and Tom Coope, Second Assistants Christopher Frith and Ryan Axe, Lead VFX Editor Ben Mills, VFX Editor Robbie Gibbon and new recruit Hannah Leckey who joined as Editorial Trainee. Plus our fearless Music Editor Cécile Tournesec, Chris Hunter and Michael Cheung who joined later in post as 3D Editors, and Nicola Ford our 3D / Post Co-ordinator (see team photo below). And most importantly our wonderful Post Supervisor Susan Novick.

In late May the production moved to the South Island of New Zealand, to Queenstown. Myself and Christopher Frith travelled with the crew, set up a cutting room in a rented house and I switched around so I was daytime on Mission: Impossible and evenings on Kingsman (doing remote VFX reviews). The rest of the team stayed in London and we shuttled MXF media and bins back and forth using Aspera.

We were in Queenstown for around six weeks where the crew were filming predominately the third act of the movie: New Zealand doubling for Kashmir on the India Pakistan border, where they would allow Tom to fly a helicopter and do some incredibly dangerous stunts on camera. It was very nerve-racking watching the footage come in on a daily basis.

The two IMAX sequences in the film, one of which is a skydive sequence and the other being the helicopter sequence, were shot on Panavision DXL cameras at 8K, mainly because they are lighter than film cameras and can record for 40 minutes (much longer than a film roll). The rest of the movie was shot on 35mm anamorphic film. However the film was shipped daily from New Zealand to London for processing so I had a bit of a delay seeing that scanned film MXF media down in New Zealand. In the meantime I would do all of my selects and assemblies using the videotap Quicktimes transcoded into Avid Media Composer. Then my team would overcut those timelines with the scanned film dailies when they arrived.

We were in New Zealand for about eight weeks then we returned to London at the start of July. We filmed for about six weeks in London then, on a Sunday in the middle of August, Tom broke his ankle doing a huge leap from one building to another near St. Paul’s Cathedral. Incredibly he pulled himself up and ran out of the shot on his broken ankle (which you see in the movie). But of course filming had to stop while he healed.

So the crew started a three month hiatus, and in that time Chris McQuarrie and I focused on fine-cutting all the sequences that had been filmed up to that point. Chris has this expression: “disaster is an opportunity to excel.” He always looks for the silver lining of any cloud and stays positive. We used the time to take a long hard look at the film and ask ourselves difficult questions about what the strengths of the film were and what could be improved. We revised all the remaining scenes to be filmed and figured out what the very best connective tissue would be. The biggest chunk was the second half of the second act with some quite complex dialogue and suspense scenes, a gun battle and then a big foot chase that we’d only just started filming when Tom broke his ankle. Cameras started rolling again in mid-November with the climactic clifftop battle filmed on Norway’s Pulpit Rock, then back to London where we finished filming around the end of February.

I was racing to keep up to camera with my edits. We finished filming on a Sunday night at midnight and then the following Thursday night we had our first friends and family screening. We set ourselves that deadline to keep the pressure on.

HULLFISH: That is crazier than the last Mission: Impossible movie. I think I remember you saying that that was 10 days after shooting before a first screening!

HULLFISH: That is crazier than the last Mission: Impossible movie. I think I remember you saying that that was 10 days after shooting before a first screening!

HAMILTON: It is pretty crazy, although we had those three months to carve out the edit. So we were a bit ahead of ourselves. The other thing to mention is that Chris only likes to use score written by the composer (on this movie we used a fantastic British composer called Lorne Balfe). Chris prefers not using temp score, so we only had about two thirds of the score for that friends and family screening, the rest of the movie played bare (which was most of the third act).

That screening was quite long. It was around 2 hours 50 mins without credits. And that was the first time that Chris and I had watched it from beginning to end without stopping, because we were editing until 6:30pm that night and the screening started at 7:30pm. It was one of those days where I was turning over reels of the movie to my team hourly from midday and they were making mixdowns and copying the media to a drive, and then I turned over the last reel at 6:30pm and we mixed it down and then rushed it to the theater, did a quick tech check and then we pressed play at 7:30pm. Chris and I watched it through with his family and loads of friends. It was a full screening, around 70 people at the Soho Hotel in London. It was a very positive reaction, which was great. But we also got some very clear steers on what we needed to refine. After that we had full recruited test screenings in the USA every two weeks, again a deadline we set ourselves.

Chris McQuarrie is a strong believer in the testing process. He really enjoys the brutality. He likes “having the water thrown in his face”, as he says. It’s always a healthy thing. It puts you out of your comfort zone and makes you reassess the film and then improve it. Tom Cruise is always at the screenings and after we all spend a short time discussing what we need to do, then we roll up our sleeves and get to work. We edit for five or six days, then we’re ramping up for the next screening by fixing the sound and music and updating as many VFX shots as possible, and that was the constant process of revision and improving the film step-by-step.

About seven weeks after the main shoot wrapped we filmed three days of pickups and I dropped those in just before we had our third preview. However we were still getting feedback from the audience about improving the pace. So we tweaked the edit further, Chris and Lorne revised some of the score, then about 10 days after that we had our fourth preview. Thankfully we got the highest score of any Mission so far. Everyone was very happy and the final running time of the movie was around 2:20 without credits.

About seven weeks after the main shoot wrapped we filmed three days of pickups and I dropped those in just before we had our third preview. However we were still getting feedback from the audience about improving the pace. So we tweaked the edit further, Chris and Lorne revised some of the score, then about 10 days after that we had our fourth preview. Thankfully we got the highest score of any Mission so far. Everyone was very happy and the final running time of the movie was around 2:20 without credits.

It’s certainly the longest Mission but it’s also the most ambitious. It has the grandest scale. It’s got an epic sweep to it, and all the reactions from people who’ve seen it now are that they’re leaning forward and engaged from the very beginning to the end. All the little chunks of plot that we need everyone to understand are landing with the audience. Fingers crossed we’ve got a really great movie.

As I speak to you, the premiere is in Paris next Thursday on July 12th 2018. We’re due to see the last visual effects shot on the 3rd, then color correct it on the 4th, and hopefully watch the DCP on the 6th. There are press screenings on the 9th in France. It’s all very down to the wire. But… “it’s not Mission: Difficult”, as Anthony Hopkins says in M:I-2.

Everyone understands the intensity of what Mission: Impossible demands. All my crew are very professional. Everyone gets on with it. A special shout-out to our wonderful music editor Cécile Tournesac, who started with us halfway through filming, worked very closely with the composer all the way through the director’s cut process, then on the scoring stage and finally on the mixing stage. She was absolutely instrumental in helping the score evolve from complete silence to the finished version and worked incredibly hard. I’m very proud of the film and I’m excited for the world to see it.

HULLFISH: It’s interesting that Cruise broke his ankle, because that happened with Harrison Ford on one of the Star Wars movies and it allowed them to re-write stuff and re-think stuff during the period where he was healing. They were really able to improve the film in huge ways because of what was basically a disaster.

HULLFISH: It’s interesting that Cruise broke his ankle, because that happened with Harrison Ford on one of the Star Wars movies and it allowed them to re-write stuff and re-think stuff during the period where he was healing. They were really able to improve the film in huge ways because of what was basically a disaster.

HAMILTON: Very similar. I think every crew should stop work for a month two thirds of the way through the filming schedule, look at what they’ve got, revise plans and carry on filming afterwards! Of course that never happens. You have to look at it as an opportunity to dramatically increase the quality of the storytelling. Time is a luxury that you very rarely have when you’re making a film. You’re usually clinging on for dear life during the white-knuckle roller coaster of filming then post-production. When you have a release date, you simply have to buckle-in, put your head down, do the work and make sure that you stay fresh, positive, and excited about the process, even when you’re in the eye of the storm. Stay calm. Tackle everything one-step at a time. But be aware of the deadlines. Your job is making sure that when you have a screening, the whole film is ready to press play on time.

HULLFISH: One of the things that we talked about a little in the last interview but you also just mentioned at the top of this interview is the workflow testing process.

HAMILTON: I’m a strong believer in figuring out your entire post workflow in plenty of time before cameras roll. On this film I wanted to try working at Ultra High Definition (2160p) on the Avid timeline. There’s a great Avid codec called DNxHR LB which is only 144 Megabits per second. That’s only 20% more than the 1080p codec DNxHD115, but you get four times the resolution, and very quickly you get spoiled looking at those pristine images (remember when we transitioned from SD to HD all those years back?). I have a 2160p 65” Panasonic OLED TV connected by HDMI to an Avid DNxIQ box attached to a MacPro. The DNxIQ behaved flawlessly. It’s very quiet and just sits behind my desk.

So I talked to our brilliant post production supervisor Susan Novick and asked if we could scan all of our film negative at 4K at Pinewood Post and then archive all of our DPX files onto a gigantic server (and LTO tapes). These 4K master files could then be converted to whatever file format we want for Editorial, VFX or the DI, which would streamline the whole post workflow. Susan agreed and worked it all out.

The daily workflow went as follows… film developed overnight at CineLab London, then delivered to Pinewood Post early in the morning. Scanning would commence immediately. And as each lab roll finished scanning, the resulting DPX files would quickly be transcoded to DNxHD36 1080p MXF files with a single LUT applied. (The digital IMAX files would simply be archived and transcoded as no scanning was necessary).

These files would be sound on a Media Composer at Pinewood, then those bins along with the picture and sound MXF files would be uploaded to us at via Aspera (for this early morning process we used DNxHD36 to keep the upload/download time short). This meant my team could start preparing scene bins and I could start viewing dailies (albeit only in 1080p) around 8am.

Then during the morning back at Pinewood our dailies colourist would do a full colour pass on every shot, and new DNxHR LB 2160p MXF files would be created with that colour applied. Those files would then be shuttled to us on a drive. We would archive the single LUT DNxHD 36 media, copy the new DNxHR LB media onto our Nexis, then relink our master clips to the new colour corrected 2160p media. So around lunchtime I would shut all my bins with the old single LUT HD subclips, give my team a few mins to relink, and then reopen all my bins with the sparkling new properly graded UHD subclips. It worked perfectly.

Pinewood would also send us the CDL (color decision list) metadata for each clip, which then existed in our Media Composer project and in the Filemaker database which the VFX team used.

Fluent Image is the company that managed the data and color pipeline on our film, they processed any EDLs from editorial, transcoded the DPX files from their huge server, then uploaded the new files (usually EXRs) directly to VFX or the DI.

The sound workflow was pretty standard. For each take there were multiple BWAV tracks with a channel 1 mix track. I like to work with all the tracks in the timeline, I know some people like channel 1 subbed out, but I get my assistants to solo channel 1 so when I press play, I’m only listening to the mix track, but all the other tracks are there in the subclip. When I assemble the scene I lay down all the production audio tracks and then later on I go back and audition the isos separately and cherry-pick the best ones so I have (what I think) is the best sounding scene. As good as the production mix track may be, there’s no substitute for crafting your own dialogue track. On this movie my Avid timeline had six mono tracks for dialogue, four monos and six stereos for effects, and three stereos for music.

James Mather (our sound supervisor) and his sound team were on Rogue Nation and they were back for Fallout. Whenever I would assemble a sequence that needed detailed sound help, we would send James the sequence and within a day or two his team would send back stems of guns or tires or engines or ricochets or whatnot, my assistants would lay those stems back into my timeline, then I would do a 5.1 sound mix. As I refined the edit of the sequence these stems would be cut and pasted and trimmed, and Chris McQ would get used to hearing the sounds that the sound designers had chosen and would start feeding back notes straight away. He’s very specific with the soundscape. It also meant that every screening had a great sounding mix.

One tip for working with stereo music in a 5.1 environment… I highly recommend getting hold of a Waves plugin called UM226 which is a RTAS (Real Time AudioSuite) plugin which you assign to the stereo music tracks on your timeline. When you press play, UM226 upmixes the stereo to 5.1 in real time and does a fantastic job (see screenshot).

In Fallout, there’s a car chase similar to Rogue Nation where we don’t use score. We use the sounds of the engine of the car and motorbike as the score for the scene and it’s terrifically effective and great fun to push the limits of the sound mix. Ultimately it was so effective that it ended up being too punishing on our ears, so we up pulled it back a bit. It was one of those sequences where we didn’t go up to 11 all the time. We learned that going up to 9 was enough, and sometimes 8 was plenty.

In Fallout, there’s a car chase similar to Rogue Nation where we don’t use score. We use the sounds of the engine of the car and motorbike as the score for the scene and it’s terrifically effective and great fun to push the limits of the sound mix. Ultimately it was so effective that it ended up being too punishing on our ears, so we up pulled it back a bit. It was one of those sequences where we didn’t go up to 11 all the time. We learned that going up to 9 was enough, and sometimes 8 was plenty.

We used a DI facility called Molinare with an wonderful colorist called Asa Shoul who Rob Hardy (our DP) has used many times. Molinare have a terrific team, I cannot recommend them highly enough. They’ve been very thorough, efficient and helpful at every stage of the process and the Digital Intermediate on this film has been one of the most pleasurable I’ve experienced, especially considering the deadline pressure to meet the release date.

HULLFISH: I believe the interview I did with the editors of The Crown, they discussed doing the off-line at Molinare.

You’ve done the two Mission movies with Chris and the two Kingsman movies with Matt Vaughn. What does that do for you to work with a director multiple times, to have that relationship built?

HAMILTON: That’s a good question. There’s a book called “Creativity Inc” about the creative ethos of Pixar. It is a brilliant book. I love it. Everyone should read it. One of the things they champion at Pixar is being able to fail creatively in safety.

To be honest the key to almost anything in life is failing then improving as a result of that. Nobody can pick up a musical instrument and play it straight away. You have to fail a lot before you get good at it. And, something we all know as editors, this film has never been made before and will never be made again, so you’re going to fail a lot before you get it right.

When you have a relationship with a director they feel safe failing with you and you feel safe failing with them. I don’t get to see Chris much during production, he’s so busy with the details of filming from the moment he wakes until the moment he sleeps, so I would throw sequences together in any way that I felt was appropriate given everything that I’d seen. I knew that Chris would want to change a lot of it, but he allows me to fail in safety. When we do sit down to fine cut, it only takes an hour or two to play and re-work the scene into a better shape, closer to what he imagined.

HULLFISH: Chris also was the screenwriter. You’re a huge fan of story. Does it help or hurt that the director also wrote the film?

HAMILTON: Oh, it definitely helps. He understands the evolution of the story. He understands the evolution of each character. He has seen the characters evolve during the filming.

HULLFISH: I would think the danger would be that he’s a little precious with his words.

HAMILTON: He’s far from precious. He is the least precious writer you’ll meet. Chris understands he’s making mass entertainment. And ultimately the audience is right. When you show the film to an audience and you hear how they respond and you listen to their notes and feedback, he’s not the guy who says, “Well I’m the director and this is how I want it to be.” He’s the guy who says, “The audience doesn’t like this, the audience is confused by this, the audience finds this slow. We have to do something about it. What do we do?” And we try various ways to fix the issues. He throws out anything in order to deliver a film plays well to the audience.

HULLFISH: I loved your expression that you said early on about Chris: that he loves having water thrown in his face. Not many people feel that way.

HAMILTON: We had a few moments in this process where we were surprised at how the audience reacted. But then you think, “You know, they’re right, and we’ve got to look at this again and try something else.” Sometimes it’s recutting a scene. Sometimes it’s reordering scenes. Sometimes it’s removing a scene. Sometimes it’s refining the score. Even small changes to the score quite dramatically change how the audience perceives the film. The very first cue in the movie is crucially important in setting the tone. That changed right until the end of the sound mix.

HULLFISH: With some of the action sequences how do you approach the less structured or scripted elements, or are they structured?

HAMILTON: They’re not that structured. For example, the foot chase in the movie was filmed out of sequence, and we found the rhythms of it later. Ethan running is intercut with Benji looking at an iPad and giving Ethan directions in order to catch his target. All that stuff was filmed with Simon in half an hour, about a month after Ethan’s running coverage was in the can, once we had a sketch of the foot chase and we understood all the little pieces that Benji would need to say to Ethan to make certain jokes work.

When you’re working on an action sequence like the foot chase, I watch through the dailies, select all the best footage and start by putting that down on the timeline. Then you whittle it right down to the very best tightest sequence you can create. Audiences are super sensitive to repetition; you have to keep everything fresh, otherwise the quality needle in their head starts dipping into the red. You’re constantly trying to keep that internal needle nudging up into the green and to minimize the red, because cumulatively a few dips into the red can add up. You refine the action sequences constantly by paying close attention to the audience reaction during screenings until you’re confident everything is working well.

Another example is the helicopter action in the third act. This is a very, very ambitious sequence where Ethan has to stop a villain escaping with a detonator. There was around seventy hours of dailies generated by all the IMAX cameras, which over many months of editing I eventually reduced to just under seven and a half minutes in the final movie. But be assured that I carefully watched every minute of dailies and picked the very best moments. Then I sketched out the scenes for McQ to react to. It was clear the sequence was going to be something special, but it took us weeks and weeks of refinement before we found the correct rhythms and pace and intercut points to make it work well in the movie.

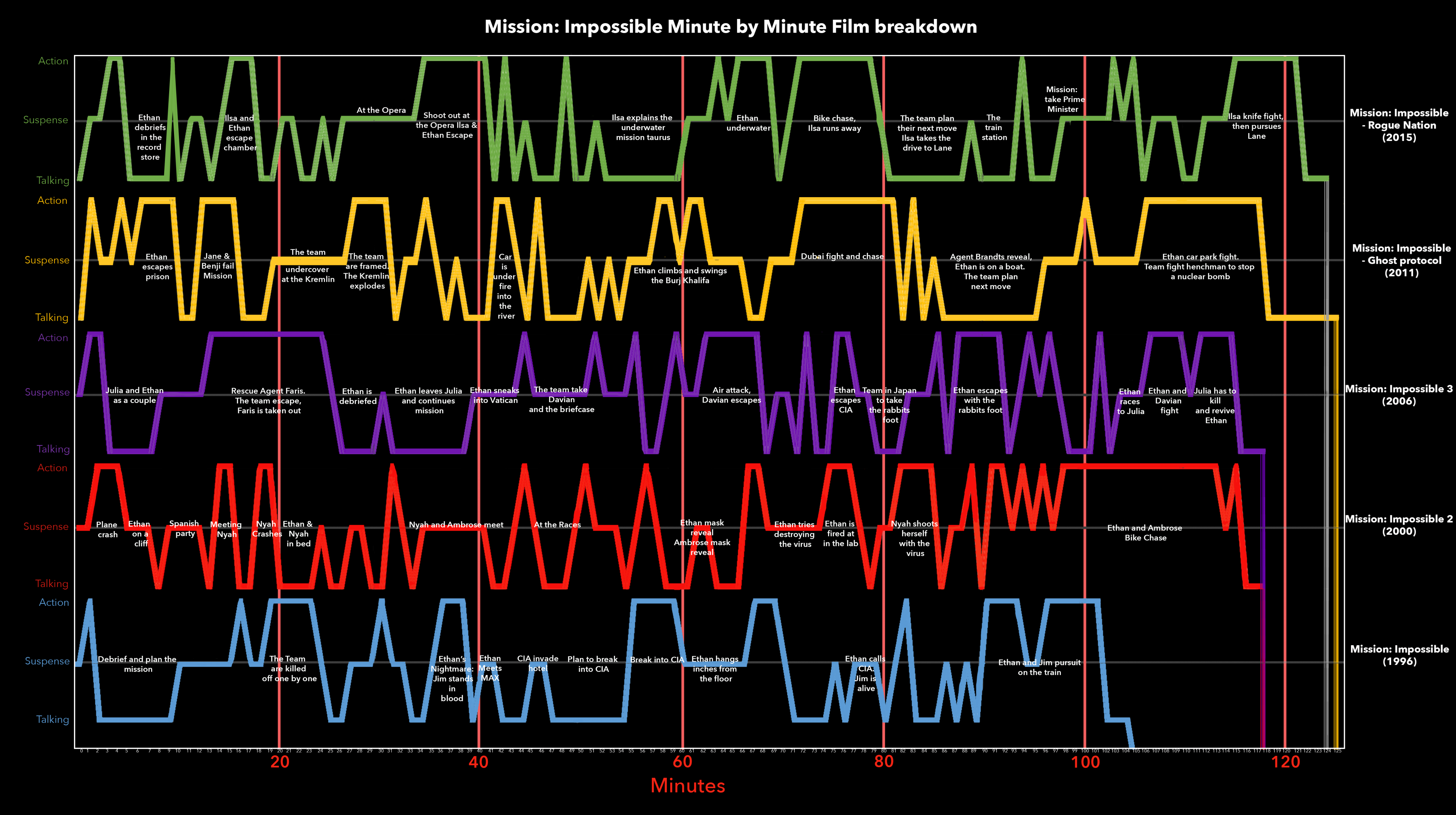

Here’s a thought about Mission: Impossible. These movies tend to play in sequences of set-up, suspense, then action. The characters talk about what’s supposed to happen, setting up the “rules” of the upcoming sequence. Then you watch that scene play out as suspense, usually with minimal dialogue. Then things don’t quite go to plan, and that culminates in a large action set-piece. Set-up, suspense, action.

On this Mission I asked my assistant Hannah to prepare a minute-by-minute graph of the five other Mission films representing the set-up, suspense and action. It was interesting to compare the movies to each other. I’ll send the PDF to you.

HULLFISH: One of the other things you mentioned in our previous interview that I thought was really interesting was that in those suspense sections you try not having music. Music is sometimes such a giveaway that if you don’t have the music it doesn’t allow the people to rely on the music to tell them what’s about to happen.

HULLFISH: One of the other things you mentioned in our previous interview that I thought was really interesting was that in those suspense sections you try not having music. Music is sometimes such a giveaway that if you don’t have the music it doesn’t allow the people to rely on the music to tell them what’s about to happen.

HAMILTON: Yeah, that’s absolutely true. On this film, we have quite a lot of music. Lorne Balfe was hired very early. Immediately he wrote about 12 suites of music, not to picture, just based just on Chris’s pitch of the story. Each piece was maybe four or five minutes long. So he wrote well over an hour of music. There was one particular cue which was brilliant. We tracked it on the movie straight away and it ended up staying on that sequence. It’s the scene where Lane’s prison truck is being driven through the streets of Paris in a police convoy. That scene was filmed early in the schedule, it didn’t have many VFX shots, and I was able to edit Lorne’s cue to picture so the sequence really rocked.

Lorne was onboard such a long time that we were able to explore the soundscape of the movie thoroughly. It wasn’t a situation where we had a composer for six weeks right at the end of the schedule and everything is a rush. The music evolved, we did a really detailed musical exploration. We could dial in the pieces of the suites that we liked to the picture very successfully and quickly. The music editor, Cécile, had an encyclopedic knowledge of every piece of music Lorne had written. She could cherry-pick little bits from each cue and track different scenes, then Lorne would take those ideas, rewrite and improve them. So it was a really pleasurable, organic exploration of the music for the film, which I think has resulted in an outstandingly good score. It’s very modern. It’s very percussion based. But it also has beautiful orchestral elements. If you’re into film music, you’re going to love the way Lorne’s respected Lalo Schifrin’s original Mission theme and his Plot theme.

HULLFISH: Talk to me a little bit about making the specific decision about the exact moment a cue gets dropped into a scene.

HAMILTON: Chris is very specific with music, how each cue is an integral part of informing the audience about the story. He uses every single tool in the filmmaker’s arsenal: shot composition, lighting, editing, sound design, music and color correction. Everything is designed to direct your eye toward what he wants you to see at every moment through the film. And music is a very integral part of that emotional journey. You may notice how each music cue weaves very specifically in order to underscore certain bits of the story. This may be quite subtle but it is very specific and nothing is by accident. For example, there is a close-up of a phone screen in the second act that tells you something important about a character. You will hear how the music is allowed to swell and really underscore that moment.

Another example. There’s a suspense sequence in a nightclub bathroom and we only hear the very deep bass thump of the music from outside. It varies in volume and tempo, but you can’t hear any specific score, which we found very cinematic and effective. There are also a few places where we don’t use music, but overall we embraced music as a way of holding the audience’s hand and guiding them through the rhythm of the story. The process of listening to audience feedback after screenings informed us that’s what the movie needed in this case.

HULLFISH: I know you’re very thorough about watching dailies but as we know, on certain days, you’re receiving more dailies than you can possibly look at in a day and still accomplish anything. Talk to me a little bit about how you approach a scene during dailies where you can’t possibly pick the perfect take for every moment.

HAMILTON: Chris McQuarrie only wanted one unit on this film; there was no second unit, which was enormously helpful. It allowed me to have a chance of getting through all the footage each day. Also, one of the benefits we had is that whenever the production moved to a different country, there was always a week or two of prep before they roll cameras. So that meant that when they got to New Zealand I had some clear days to finish assembling footage from Paris. When we got to London I had some time to finish assembling everything from New Zealand, apart from the helicopter chase which took months.

There was one scene in London with seven pages of dialogue. Multiple eyelines and multiple characters. Wides and mediums and overs and tights and specials. It took me two days to study that footage. And then another two days to roughly assemble the scene. But I knew I had to be thorough, because it’s a very complex scene with loads of different character beats and I can’t short change it. It’s got to be right. So other dailies were put on the back-burner until I’d finished this scene.

The secret for me is that I get my assistants to prepare line strings, which your readers may be familiar with, which enable me to review all shot sizes of a particular line of dialogue very quickly, and later swap out takes efficiently with the director if they want to try something different.

During filming in London, I was lucky enough to be picked up by a car every morning at 6:20am and I would watch dailies for an hour on my laptop. I used an encrypted 512GB SD card that would hold several days of DNxHR LB MXF files (see photo). That bad boy worked flawlessly, even when watching multiple camera streams. When I arrived at the studio I would copy a bin over with my laptop work. At the end of the day the same thing would happen. I’d get in the car and continue working on my laptop for an hour before I got home.

During filming in London, I was lucky enough to be picked up by a car every morning at 6:20am and I would watch dailies for an hour on my laptop. I used an encrypted 512GB SD card that would hold several days of DNxHR LB MXF files (see photo). That bad boy worked flawlessly, even when watching multiple camera streams. When I arrived at the studio I would copy a bin over with my laptop work. At the end of the day the same thing would happen. I’d get in the car and continue working on my laptop for an hour before I got home.

HULLFISH: That’s definitely worth it to the production.

HAMILTON: For sure. Absolutely.

HULLFISH: You are a student of story as you mentioned before and turned me on to a great book called “Into the Woods.”

HAMILTON: It’s amazing!

HULLFISH: I love that book. Any other recent finds in your study of story that you’d be willing to share?

HAMILTON: I best one is “Creativity Inc,” the Pixar book I mentioned earlier (see photo). In the last year I’ve been buying everyone that book and leaving copies in my cutting room. It would benefit any creative person, or anyone in a position of power who works with creative people and is keen to enable them to be more creative, to read that terrific book. Allowing people to fail safely is, I think, the biggest takeaway from that in terms of evolution of story.

HAMILTON: I best one is “Creativity Inc,” the Pixar book I mentioned earlier (see photo). In the last year I’ve been buying everyone that book and leaving copies in my cutting room. It would benefit any creative person, or anyone in a position of power who works with creative people and is keen to enable them to be more creative, to read that terrific book. Allowing people to fail safely is, I think, the biggest takeaway from that in terms of evolution of story.

HULLFISH: Let’s talk about how you deal with previz. I assume on a movie like this, that it was heavily previzzed.

HAMILTON: Certain sections of the action were previzzed. The HALO jump, for example, because that sequence is a single shot deal, “Birdman” style with a couple of hidden stitches. A very ambitious, technically complex shot which will never be filmed again. You see Tom Cruise jumping out of a plane at twenty five thousand feet into a lightning storm, and there’s unlikely to be another movie star who will attempt something so extraordinary. Parts of the motorcycle chase and the heli crash were also previzzed. But not a huge amount of the movie.

HULLFISH: I’ve talked to your assistant editors and they love working for you. Tell me about mentoring them and what you may see as your role in advancing their creative and editorial abilities.

HAMILTON: I ask for their notes constantly. I encourage them to cut their own versions of scenes, but the relentless schedules means often they don’t have time. They’re always welcome to dip in to my workshop bins or watch the cutting copy any time and give me notes, when they do those notes are excellent. It looks like my next film will be in Los Angeles and sadly I won’t be able to take any of my team. So I’m helping them find jobs if I can.

HULLFISH: You’ve had a chance to work with some fantastic editors. You’ve talked about your time with Pietro Scalia and you also worked with Lee Smit. What are some of the things that stick out in your mind that you picked up or learned or stole from them?

HAMILTON: Pietro taught me: don’t edit what you think they want to see, edit what is right for the scene. One of my worst habits was trying to imagine what the director wanted to see and then engineering the scene towards that using all the available coverage, whereas what you should do is cut what you feel is the best version of the scene, and if certain coverage doesn’t work, don’t use it.

and Tom Cruise (right) on the set of MISSION: IMPOSSIBLE – FALLOUT, from Paramount Pictures and Skydance.

I was also in the terrible habit of making too many cuts, and Pietro would often simplify the scene and it would improve enormously. Today I have a greater appreciation for what he was teaching me. I hope that my editorial aesthetic has changed and that I understand the power of a cut more, and why you should make the cut.

One of Lee’s top priorities is always staying up to camera. He felt unprofessional if he fell behind. Lee is incredibly fast, and I hope that eventually I’ll learn to work as fast as he does. Also, Lee is confident about his opinion, he would speak up and be honest about the strengths and weaknesses of the film, and how to improve it. I think that my own internal barometer and instincts about what a film needs to improve is a lot stronger than it used to be.

Pietro and Lee (and also Martin Walsh, who I worked with on Eddie the Eagle) have an enormous sense of calm and professional presence that comes from years of experience and confidence in their ability. People can sense that immediately.

HULLFISH: Eddie, I’m not sure if these scenes that I got from the studio are exactly as you cut them, but could you comment on any of these scenes? What were the challenges? What led you to structure them like you did or make these editorial choices.

This is the start of the single-shot HALO jump sequence, there are no edits here. Although the logistics involved in filming this were jawdropping, you can see a behind-the-scenes video online. We filmed this in Abu Dhabi and I was in a trailer on the military base editing with McQ during the day while the skydive team rehearsed, then in the evening they would film for three minutes when the sun was exactly the right height in the sky.

This is a cutdown version of the bathroom fight which doesn’t reflect exactly how the scene plays in the movie. But you can see how we chose to let the action play as long as possible without cutting so you can watch and feel the punches land, plus use wider shots so the geography is clear.

This is a cutdown version of the scene where we meet Angela Bassett’s character. We chose certain lines to play on certain characters for specific reasons. This scene is also the start of the antagonism between Hunt and Walker so it was crucial the audience felt that.

This is a cutdown version of the scene where Ethan is ambushed by hitmen in the jazz bar. We try to keep the geography as clear as possible during the action, while keeping the energy up in every shot. Notice we use the same action of the final goon swiping his knife at Ethan from three different angles in order to accentuate the feeling that Ethan is on the back foot, before the Widow helps him out by stabbing that goon in the chest.

This is a cutdown of the epic motorcycle chase in Paris. They filmed that Arc De Triomphe section in 90 minutes starting at 6.30am one Sunday morning in April 2017. Notice how we hold on the wide shot showing the Arc for several beats so we can enjoy the dramatic sight of Tom riding that bike for real against traffic, but use shorter more energetic shots before and after to remind you of the chaos and danger.

HULLFISH: Eddie, it’s always a pleasure talking to you. You are always so passionate about pushing your abilities on the exciting projects you work on. Thanks for talking with me.

HAMILTON: Thanks for inviting me to talk to you Steve. I hope your readers enjoy the movie.

For a few more exclusive questions and answers from this interview, check out the Frame.io Insider

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish

The first 50 interviews in the series provided the material for the book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV Editors.” This is a unique book that breaks down interviews with many of the world’s best editors and organizes it into a virtual roundtable discussion centering on the topics editors care about. It is a powerful tool for experienced and aspiring editors alike. Cinemontage and CinemaEditor magazine both gave it rave reviews. No other book provides the breadth of opinion and experience. Combined, the editors featured in the book have edited for over 1,000 years on many of the most iconic, critically acclaimed and biggest box office hits in the history of cinema.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now