Oscar nominated editor Joe Walker, ACE, recently cut the movie Widows for director Steve McQueen. It’s their fourth feature project together starting with Hunger (2008), Shame (2011), 12 Years a Slave (2013) and even a short film called Ashes (2014) preceding it.

Walker has also edited Blackhat (2015) for director Michael Mann and edited a string of collaborations with Denis Villeneuve: Sicario (2015), Arrival (2016) and Bladerunner 2049 (2017).

(Please note that some of the movies above have links to our previous four interviews. If you enjoy this interview, definitely go back and check out more great wisdom from Joe in his previous interviews. Please also note that the video clips in this article have been revised by the marketing department and do not quite represent Joe’s actual work.)

(This interview was transcribed with SpeedScriber. Thanks to Martin Baker at Digital Heaven)

HULLFISH: You’ve been a busy man with several other directors, but are finally getting back together with Steve McQueen for this one.

WALKER: Steve first mentioned Widows when we were cutting 12 Years a Slave, so I’ve known about it a long time. But when it got a green light, I was in the middle of Blade Runner 2049 and couldn’t join him. Some months later I got a call inviting me to join Steve for Director’s cut. So we wrapped Blade Runner on a Friday and headed straight out to Steve’s hometown of Amsterdam on a Monday.

It appealed to me to shuffle things up and work on a project with a slimmer VFX count and a pared down Editorial team – to jump from an imagined future to an all too real present.

Chris Tellefsen and Joan Sobel looked after the baby before I arrived and contributed a lot, so they have Additional Editor credits too.

HULLFISH: I’ve interviewed both of them. That’s a talented crew with the three of you!

Tell me a little bit about intercutting the stories at the beginning of the movie. We’re meeting the principals and establishing the storyline, and to do that you intercut between this opening heist gone wrong and the lives of the people that the heist leaves in its wake.

It’s a short, confrontational opening taking only a few minutes to lay everything out, but it also manages to point to the tensions in those relationships. For example, with Liam Neeson and Viola Davis in bed – as he lurches towards her in a kind of aggressive play, it sharp cuts to screeching brakes and the back of the van. The cuts try to draw out what lurks beneath in those relationships.

HULLFISH: That’s a great description of that. As far as editing that, as it was scripted, were you aligning your edits to the script, or were you more interested in finding those moments where you could show some aggression in one scene leading to an aggressive moment another scene?

WALKER: Well, first, some background on the script: it’s Gillian Flynn and Steve McQueen’s work but Widows started life as a British TV series written by Lynda La Plante. It was must-see viewing back in the 80s. When Steve first mentioned it, I remember saying “Widows?” because the first thing that came to mind was the big hair and shoulder pads. It was unfair of me because there’s so much to admire in the original piece. Lynda La Plante created more iconic female roles than anybody at the time: the character of Jane Tennison, played by Helen Mirren in Prime Suspect, is hers. What Gillian and Steve have done with the story is a miracle. Transplanting it to contemporary Chicago was inspired.

As far as the opening sequence goes, yes, it was scripted that way. Obviously, there’s many refinements and changes of order and little re-writes, things that are just commonplace in the cutting room. Steve wanted it to start like a hare out of the gate: to set a cracking pace with little in the way of shoe-leather.

HULLFISH: You rarely saw anybody walking anywhere or driving anywhere. There were very few people walking through doors.

How long was post-production?

WALKER: We started in Amsterdam in August 2017, then worked in London from January to July 2018. So eleven months spent constantly refining and tweaking and shedding every stray hair that we could.

Once we had something close, the film was tested with invited audiences — initially to friends and family, then more formal NRG-type screenings. The story really benefitted from that. To make a rollercoaster ride, you have to thoroughly stress-test it. A tiny example is a joke where Alice is told to go and buy guns. An earlier cut had a longer line from Veronica and the timing was different. At the screening, the only people laughing were me and Steve, it didn’t get the reaction we wanted. So we piled back into the cutting room and edited it more brutally. We shortened Veronica’s line and then a piece of music slams in to reinforce: yes, that was a joke. The next time we screened there was a big laugh. I suppose there are a thousand of those moments you finesse, once you know how an audience reacts.

It’s one of those films where you really have to be in step with the audience or just ahead of them. You have to predict exactly what information the viewer will have got, what they are expecting next and just stay ahead of them so that you can deliver big surprises and reverses of fortune, all the things that make it a very gripping film to watch.

HULLFISH: It was definitely one of those films that how and when information is parceled out was critical. Can you describe any of those discussions?

WALKER: The order in which we discover things did change so that the audience didn’t know things too far ahead of the characters. There was also the benefit of a small amount of new material shot while we were in post, to shore up some ideas. For example, a little beat where a child picks up a weird toy. It’s something that goes past so quickly and you may not see where it’s leading but it clicks into place down the line. One of the most delightful things I’ve heard is people seeing the film a second time. They see it differently.

HULLFISH: It’s similar to Arrival — which you cut — because when I go back and watch that again, I pick up on all kinds of clues and little things that you didn’t realize had significance the first time.

WALKER: Exactly.

HULLFISH: Is it difficult to construct a film like that?

WALKER: This movie has 81 speaking characters, 75 locations, originally it had 146 scenes. That tends to turn the Sudoku puzzle from ‘medium’ to ‘evil.’

Talking of Arrival – a lot of my career can be attributed to a very simple editing trick which is: if you have a shot of somebody looking very thoughtful and then you cut to something, then you’re suggesting it’s what they’re thinking about! That was a big part of Arrival as you know but also in Widows, there was amazing material from Viola that gave me a chance to be quite free with those moments where we deep dive into her character and discover what took her to where she is.

HULLFISH: There was a moment near the beginning of the film with Viola reflected in a mirror as she prepares herself for a funeral… very powerful…. cool fringing of the image because of the mirror… I suppose with a performance like that, you just stay out of the way.

WALKER: Yes, Viola lets out a howl of grief and then there’s a moment where she tries to collect herself. One of the themes of the piece, I suppose, is public and private faces. Reflection shots are something of a feature of this film – one I love is in a café, where you see mirror images of two of the widows on a pillar. It reminds me of a much-loved feature of 70s heist movies: the split-screen.

Viola’s character, Veronica, is the main spine of the story. The placing of the mirror sequence you mention and how long it’s held was a way of anchoring the story with Veronica while so many other characters are being established.

The joy of it for me is that once we get everything up and running, we’re allowed to head off on some magical left turns. For example, Reverend Wheeler. You don’t know how he’s going to fit into the story or even where he is at first. That first shot of him was a one-take wonder, by the way. That was Jon Michael Hill’s first shot of the day and his only close-up take. That guy was just on fire. There’s a hold on him at the beginning, quite a decent chunk of time just looking at him — somebody that we’ve not met and we have no idea what his connection is to any of our characters. It’s something that reminds me of a scene in 12 Years a Slave where we held for a while on a lady’s face. There’s suspense, not knowing where we’re going. Then she starts singing. That was the River Jordan spiritual, sung at a funeral service on the plantation.

HULLFISH: That’s a huge task to just keep everybody alive.

WALKER: It’s like herding cats, trying to get all of these storylines together. But everyone has their moment. One example of that: the character played by Lukas Haas, a businessman who uses ‘sugar daddy’ websites for dating. You’re inclined not to like him and yet there was this rather beautiful moment where he says something very charming and reassuring. I remember we got excited about holding on that just a beat or two longer than expected. It gives time to wonder what we think of him, and perhaps allow ourselves to be a little charmed by him. We wanted every character to have their space and the actors were all firing at a really high level, so there was a huge abundance of those moments. It was just having to pick the right ones to highlight.

You don’t want to do that tedious thing about going ’round the houses, or spinning plates. The best performers of the classic ‘Chinese plate trick’ are the ones who control everything so that the audience’s eye is drawn to the plate dangerously succumbing to gravity. At the expert moment, they come back to it and give it a spin, only for a new plate to become perilously close to dropping. There’s a showmanship to making that an engaging narrative. In film terms, the bad version would be: this happens while that happens and meanwhile this is happening. Well, if you have seen too many “meanwhiles” you lose drive —all of our character arcs have to have time for their own trajectories while you’re maintaining a whole story momentum. Alice has a huge character arc. She goes from ditzy and submissive to developing a taste and a talent for crime, and through that, her independence. You can’t shortchange any of those steps.

HULLFISH: Let’s talk about your experience in working with Steve McQueen. This is a long-term relationship at this point. How do the two of you relate and communicate in the cutting room?

WALKER: We’ve made four films together over a span of eleven years. With Steve, I feel like a pack of hounds investigating where the prey is. He has the patience and determination to seek the best cut that we can make from this material, so we keep digging down into the telling details. It’s a hard thing to describe the dynamics of that conversation. Over four films, it’s just what we do.

The great thing about my collaboration with these directors, Steve and Denis (Villeneuve), is that we’re very like-minded in what we identify as problems to solve. How to solve them is the easy bit. When I say “a problem,” it isn’t necessarily that something’s bad. It’s just: “What do we need to tell this story the most interesting way.” So much invention comes out of that.

An example: there was a car scene between Belle — Cynthia Erivo’s character — and Veronica. As filmed it was a very heartfelt conversation between the two. But we had a hunch that it took some steam away from a key dialogue scene about to happen. We ended up transforming it into a scene without dialogue. It works because they’re two people who’ve just been through heavy trauma. How to do this is relatively easy, just some simple Avid picture-in-pictures. The challenging thing is knowing what the problem is.

HULLFISH: So a problem is not really a problem. It’s just an opportunity to do something better.

WALKER: That’s a great way to put it. Finding those opportunities, you have to go into them fearlessly. To discard something world class is tough, but you may have to do that to benefit the overall pace.

HULLFISH: That also sets up another dialogue scene later on: making that dialogue more important.

WALKER: Exactly and that’s what I meant by pace. I always think of this: Think slow, Act fast. This was the name of a piece of music by Michael Nyman years ago. The notes are very busy but underneath it, the structure is tectonic-plate slow. You’re trying to get all the surface detail to serve a deeper underlying pace in the film – you have to be conscious of that underlying tempo when you’re editing. If you have two dialogue scenes back to back, one might suffer at the hands of the other. Everything depends on where you are in the story. There are times when it’s good to talk and times when it really isn’t. That was one where not talking felt a very human thing to do. Something I’m really driven by is the dance between the actor’s eyes — the intensity of eye contact. That car scene has the most tremendous looks between the characters. That was where the gold was.

HULLFISH: And to get that dialogue-free version to happen, you said you needed to use a split-screen — obviously invisible — to get it to work?

WALKER: Yeah. I used to call them “lefty rightys.” When I started with Steve, years ago, we made only one or two VFX shots, just very deliberate effects. In Hunger, for example, the beating of the inmates on one side of the screen in a different speed from the Riot Officer on the right who’s just dealt it out. We’ve gone from that to a much bigger number of VFX shots that are all part of the new editing toolbox. They might be combining the left-hand side of one take and the right-hand side of another, or many elements stacked on top of each other. It might be an invisible edit or a speed adjustment, or removing a blink. This film’s no exception. You want to fully control things and now, relatively cheaply, you can control things, which opens the door to new solutions. I’m working with a brilliant VFX editor Javier Marcheselli. He can quickly create a temp shot on Nuke to prove an idea is going to work. Then you’ve got a convincing image you can put in front of an audience before you commit to it financially and the VFX vendor takes it over.

HULLFISH: There’s a very interesting scene in Widows that is a oner — or at least looks like a oner. It’s a shot of Colin Farrell getting into a town-car and leaving a poor neighborhood and driving to his wealthy neighborhood. The entire scene is played with the camera on the hood of the car pointing to the side of the street as the poor neighborhood passes by and continues unbroken as a conversation happens in the car that you don’t see and the camera pans across to the other side as we arrive in the wealthy neighborhood — all in the course of about a minute or two — from poverty to privilege. Was there any coverage of the conversation in the car?

WALKER: Steve and Sean Bobbitt’s ballsy decision was to shoot the scene only that way. I had some flexibility with what we hear from Colin Farrell’s character, and we gave his assistant Siobhan (Molly Kunz) a more substantial thing to say about how you become mayor in this town. I cherished that shot so much, it’s a signature move. And a very bold way of expressing the idea of public and private faces. The meaning of the sound and image diverge. In audio terms, we’re inside the car hearing the intimate thoughts of Colin Farrell’s character as he drives away from a rundown neighborhood. He’s delivered a speech of support to the community there, but as he steps into the car it’s obvious that he doesn’t give a damn for them. The shot shows how close, geographically at least, are the rich and poor.

HULLFISH: True, because if you edit, you’d lose the sense of how close they are to each other. As a Chicagoan, I definitely felt — to use a cliche — that Chicago itself was a character in the movie. So it’s a great use of a oner — or at least something that looks like a oner.

WALKER: There was a podcast which was about a oner in a film I’d cut. It gave me tremendous pride that they spotted six invisible edits that I didn’t actually make but missed a massive one straight afterward. Editing is creating the illusion of reality. Every trick is there to enhance and service the efficiency of the story and the effectiveness of its communication. To me, there’s no shame involved in this. It’s not documentary. Our duty is only to make it resonate.

HULLFISH: You mentioned giving the assistant stronger dialogue. That was ADR?

WALKER: I liked that you really got to hear her speak her mind in that scene. In the rest of the film, she barely says much. It was part of giving everybody their moment, everybody having depth.

HULLFISH: I’m going to talk to Hans Zimmer. What kind of conversations and interactions did you two have on the music and temp for this film?

WALKER: I’ve known Hans a long time. He’s cinema’s “parfit gentil Knight.” As usual, me and Steve avoid score as much as possible in the cutting copy, but we did use a couple of temp tracks when it came to test screenings. We knew there was going to be quite a lot of source music in this one, music in the hairdressers or in the bars. It left Hans to supply what our cuts alone couldn’t deliver.

He wrote a kind of ‘breathing’ music for Veronica, so full of yearning and sadness. What amazes me was how he managed to do that in a major key. I think it brings a certain longing for better times, which felt very correct for Veronica. I noticed his use of major keys in Blade Runner 2049, too. Five minutes after Denis and I showed Hans our cut of Blade Runner, he figured out a melody which had all the longing we desperately needed for K’s character. It’s a feeling similar to the Mahler piece used in ‘Death in Venice’ – a long phrase always edging toward resolution but never quite gets there. For it to be in a major key is just totally unusual.

The other type of music Hans gave us was more rhythmic material to support casing the joint and the heist itself. Action music can often be delivered by a huge orchestra, dozens of percussionists and a wall of brass. But sometimes a quartet is bigger in terms of its intensity. I think of some of Max Richter’s pieces like that: five players that give you all of the depth and warmth that you need. So the idea with the heist music was to create a small band: Double bass, drums, and a prepared piano. A bit like the women who have to work together, out of type. There are cross rhythms playing against each other, they’re syncopated rhythms but they’re united in pulse. So it has that quality of things starting to click together. Hans went and recorded all manner of noises, bashing the double bass with sticks and plucking the deep strings of a piano. His hands were black and blue at the end of that session. He got physical.

The music has such a big part to play in the editing because there is a moment which I can’t spoil but it’s a big one near the end of the film and certainly, when I saw it in Toronto there were many clapping at that point. One big reason for that is the placing of the music at the perfect spot. Which exact frame that music enters, or whether it’s 3 or 4 db louder or quieter makes a massive difference to the success of that cut.

HULLFISH: Hans is very skilled in deciding when and where and what to put in as music. Do you still feel like you — as the editor — that’s your job to decide?

WALKER: We were living with temp tracks for a fair while and they definitely indicated where we needed score and what pace of music would work. But we wanted Hans to have complete freedom in what he does. One of the great things about Hans is how he talks to filmmakers about music. A composer’s and a director’s language is often different. Many great directors are not concerned with Italian words like Adagio or Largo. With Hans, one of his great skills is being able to talk to filmmakers about story and character and understanding what’s needed. First and foremost he’s a film-maker. Hans is always very kind about my editing. He points to its musicality and how we play with sound and sound effects and silence and the melody of the actors’ voices. I love the collaboration with Hans.

HULLFISH: When you’re temping, do you wait until you’ve got a longer sequence, or even a whole reel assembled before you start thinking about temp?

WALKER: Temp was relatively late. In Amsterdam, during the 10 weeks of fine-cutting, we mostly worked on the source music tracks – which song to play in the bowling alley, for example. That’s partly from necessity because those tracks have to be cleared and that can be a protracted legal issue. We kept away from putting score into the film for a long time until we had the structure of the film really fleshed out. That’s the same for Denis (Villeneuve, director of Bladerunner 2049). We spend as much time working without music as possible, just to give the cut the hardest possible investigation in the coldest possible light. On Sicario, there were times when we cut with the speakers off. In the music industry, mixers often review on a cheap £20 ‘Pifco’ speaker. They do that to check, “Does it work, even on this?” Cutting without music is a bit like that. It’s dry, but knowing how important music WILL be, you make sure you build it into the fabric of the film, giving it the necessary space.

HULLFISH: How much finessing are you doing smoothing audio transitions adding room tone, temp sound effects, gunshots?

WALKER: Particularly with dialogue, I’m doing a huge amount. I’m listening to every single take and listening to every version of a line. Cheating dialogue in order to just make it 5 percent more “this” or 10 percent more “that.” We had a brilliant sound team: James Harrison, Gilly Lake, and Paul Cotterell. It was great to see Paul again, he was our mixer on Shame. He was so over and beyond what the budget could afford on Shame that we were very happy to have him back. I’ll give you an example: in Shame, Brandon’s LP collection was something of a feature. We’d chosen Glenn Gould playing Bach, kind of architecturally controlled emotion. I remember Paul going on eBay and buying up everything on vinyl because it just sounded warmer and more authentic than the CD audio we’d temped with. Sorry, I drifted away your original question, I think.

HULLFISH: How much sound work do YOU do during picture editing to make your picture cut works before the rest of the team dives in?

WALKER: There are thousands of audio edits. Like 20 times more audio edits than picture edits. It’s a really thorough investigation of the material in every conceivable way. There is no stone unturned and that applies to both video and sound.

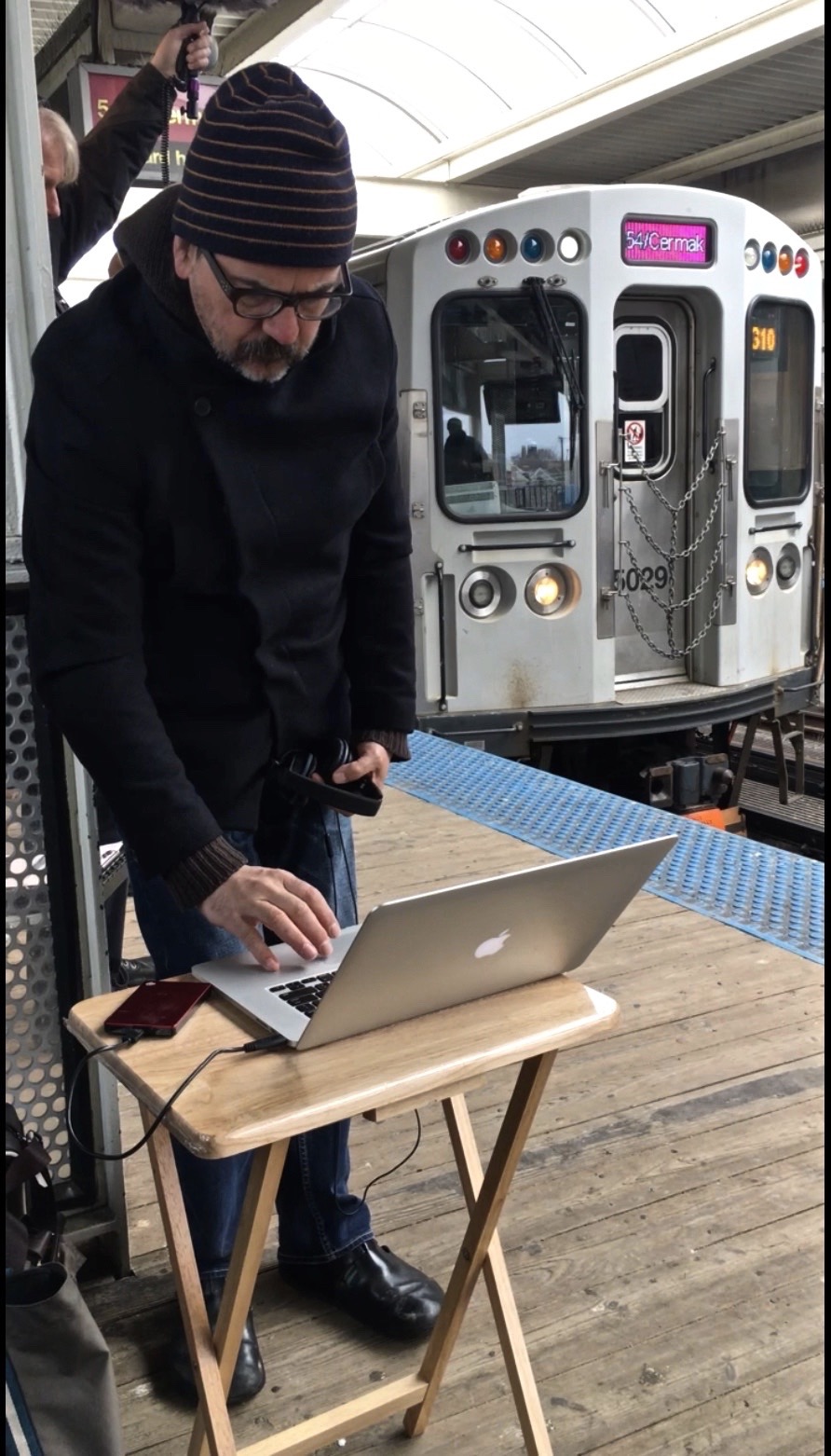

ADR is a big job on a film with 81 speaking parts, but Paul was always trying to improve takes that had been wrecked by airplanes overhead, or passing L trains. We had really good location sound to start with: a local Chicago guy, Scott D. Smith.

He was a really good sound recordist, I have to say. iZotope RX has had a huge impact on movie sound. Kind of Photoshop for audio, isn’t it? I think it’s revolutionized what we do. The thing I’m most conscious of when I’m showing somebody a cut is hearing sound bump in and out. It really kills the illusion for me. So I spend a stupid amount of time making keyframes and fading sound up and down. I’ll add reverbs and EQs, little speed adjustments. Sometimes pitch-shifting just to help emphasize a particular syllable. I’m loving the new nested audio suite on Avid.

Here’s a section from the first assembly timeline. There are some picture cuts but actually, it’s designed to look like one shot. I’m working on the dialogue across 6 mono tracks (which can either be the sound recordist’s mixdown track or original tracks which I’ve pulled in for an individual character’s clean radio mic). There’s space on the timeline for me to sketch in sound effects (4 stereo pairs) and music.

Here’s an overview of the final cut, it’s labeled ‘21st fine cut’.

By this stage of the process, 21st fine cut, I’m working with the original 6 tracks of dialogue from the assembly but 90% of them are mixed to -∞ on the audio mixer tool (i.e. silent). Tracks 7 and 8 are the mono dialogue stems from a viewing mix. So I’m playing the premixes until I come to a scene I have to recut. That’s when I’ll lift out the premix for the section, return the original dialogue tracks to their normal volume, and make a patch edit.

The Sound FX are laid on tracks 9 to 14 and have been split by the dubbing team into two pairs of spot FX and one pair of backgrounds. Tracks 15 and 16 are for new sound effects not in the premix. Tracks 17 and 18 are for the music premix, with 19 and 20 as an ‘overflow’ pair.

I’m changing my approach, though. I’m planning to use the ‘mute clips’ command on the timeline so that it’s more obvious to everyone where I’ve patched the original dialogue tracks.

Incorporating premix stems is a lovely part of the process that just didn’t exist for me when we were doing Hunger. There was no viewing mix.

HULLFISH: Because you were doing the early screening mixes yourself within the Avid?

WALKER: Yes. And on Hunger, they couldn’t pay for me to stay on through the mix, so I just went to the dub house on my own dime. Hunger was a one million euro film. And they spent most of that money on the set. It certainly didn’t go to the actors or the editor. I didn’t have a sound team working during the edit so I had to find all my own sounds to get me through viewings. It was a good research project though. I watched every documentary I could about H Block. I traveled to the prison site to work out what trees and birds were nearby and whether those roads were there at that time in the early 80s. I remember reading a book about how prisoners were taunted by the guards, or how the Hunger strikers were teaching each other Gaelic at night across the hallways, which gave me some ideas about the sound world there.

HULLFISH: I want to ask for a bit of advice. On certain scenes that I cut, I find it very hard to re-cut or re-imagine them. Other scenes I find it easy to do a different version. Do you have a trick to reworking a scene or do you feel like maybe that’s just because you’ve got that scene where it wants to be and it wants to be that way?

WALKER: I think it’s all about knowing what the problem is. It sponsors a huge amount of creativity when I know what the problem is. If I’ve worked out what’s missing or what’s jarring about a scene as we have it cut —you think about what it could be like, then it opens the doors to hundreds of ways of fixing it, whether it’s changing the order of dialogue or removing some dialogue or rewriting some of the dialogue while you’re on the back of their heads or adding music… the tools which are available to us: they’re myriad. It’s a whole lot easier if you know what the problem is. You have to imagine what the scene could be, instead of what it is.

I think you and I, and all editors to a degree, our comfort zone is straining on the leash. We know where the bones are. We have an instinct from seeing thousands of films. So we’re just pulling on the leash, sniffing treasure.

HULLFISH: That’s kind of what you were talking about with you and Steve “being a pack of hounds.” Both of you were sensing it and smelling it and going towards it together.

WALKER

Yeah. Absolutely it’s a collaboration like that.

HULLFISH

Joe, as always, it was a great pleasure to discuss editing with you. Thank you so much for your time and all of this great editing wisdom.

WALKER

My pleasure. And thank you for all the knowledge you spread – these are an amazing series of articles you’ve toiled on, props to you.

The first 50 interviews in the series provided the material for the book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV Editors.” This is a unique book that breaks down interviews with many of the world’s best editors and organizes it into a virtual roundtable discussion centering on the topics editors care about. It is a powerful tool for experienced and aspiring editors alike. Cinemontage and CinemaEditor magazine both gave it rave reviews. No other book provides the breadth of opinion and experience. Combined, the editors featured in the book have edited for over 1,000 years on many of the most iconic, critically acclaimed and biggest box office hits in the history of cinema.