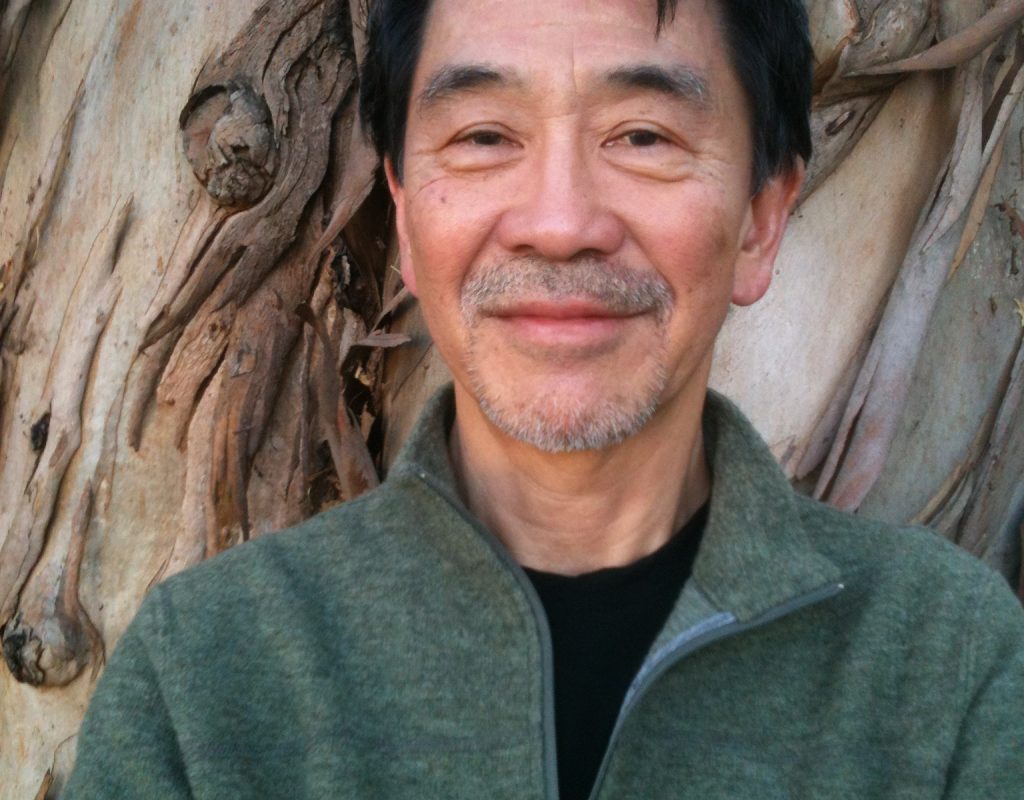

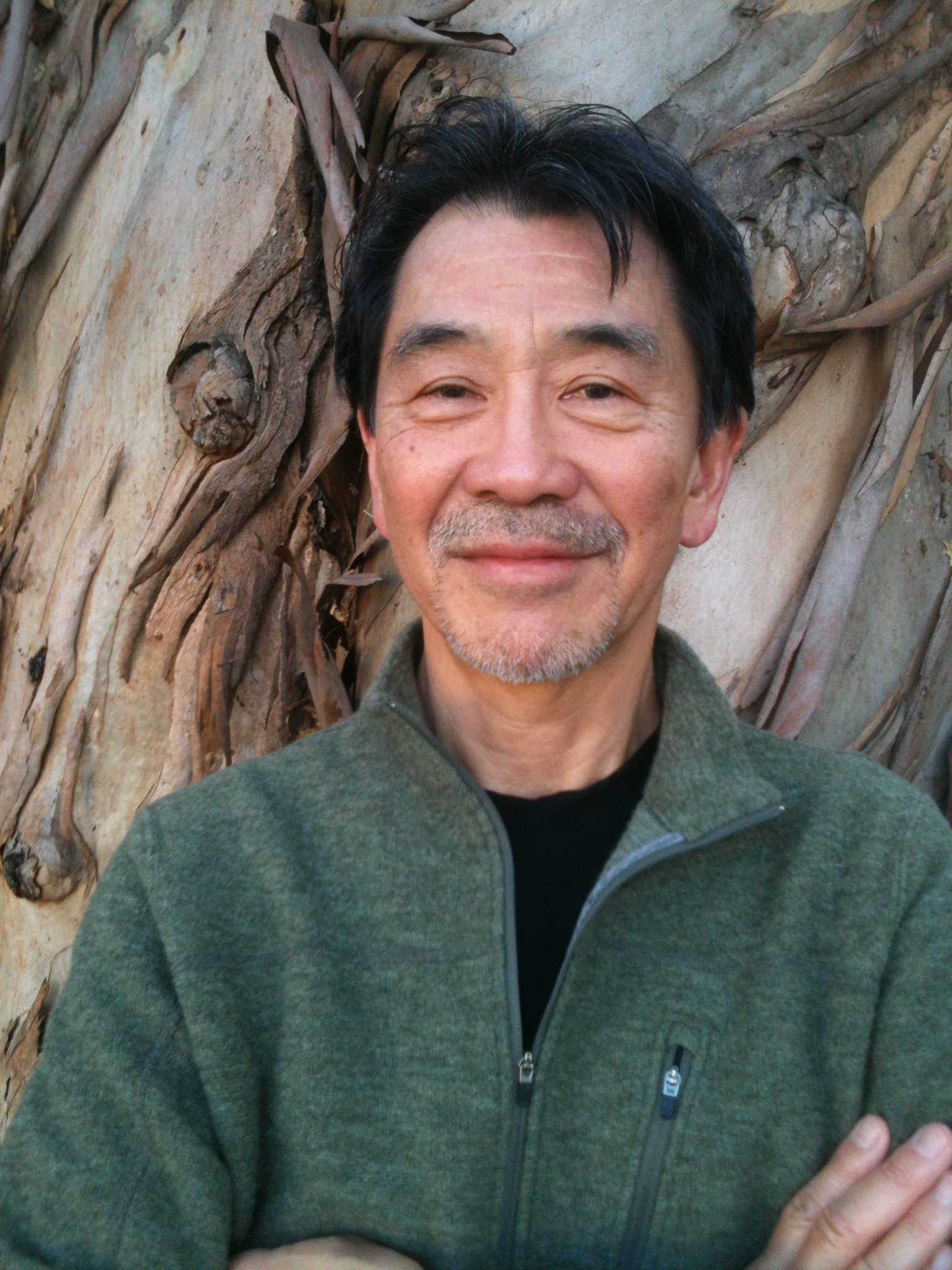

Oscar-winning editor, Richard Chew, ACE, has cut so many iconic films that I’ve been “hunting” him for a while, trying to get an interview. Having edited The Conversation (BAFTA nominated), One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (Oscar and Eddie nominated), the original Star Wars (now called A New Hope, for which he won an Oscar for Best Editing), My Favorite Year, Risky Business, Shanghai Noon (Eddie nominated), I Am Sam, and Bobby – among many more – he was a treasure trove of wisdom that I wanted to reveal to the Art of the Cut readers.

Throughout his illustrious career, he’s been interviewed numerous times, and when I finally reached him, he didn’t feel there was much more he could add to the discussion. I persisted. Finally, (very nicely) he asked me to put my money where my mouth was and do some homework. He gave me the titles of six movies he’d be willing to discuss. If I would watch them all and send a list of questions, he’d consider an interview if the questions interested him. I did my homework. It took a while to watch all of the films critically. I sent my questions, and Richard agreed to an interview, with the lovely compliment: “You, sir, are doing a very thorough job in viewing the films I suggested for discussion. You have an editor’s eye and awareness.” With that, we began an in-depth discussion of his filmography that lasted more than two hours. Buckle up.

(This interview was transcribed with SpeedScriber. Thanks to Martin Baker at Digital Heaven)

HULLFISH: I was watching My Favorite Year and you did so much of that comedy using two-shots and wide shots, which I think is great for comedies. Is that something you agree with?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fTjNQ2Jkiio

CHEW: Well in that case, for sure because of the confidence of the direction and of the actors. I don’t normally do that because, as you know, a lot of editing is to compensate for the lack of timing and a lack of performance. I am not a fan of making cuts for the sake of making cuts. In the case of My Favorite Year, Richard Benjamin, even though he was a first time director, had been a stage actor as well as a film actor and he’s worked with people that had the timing down and this was in the days, almost 40 years ago, where there was a rehearsal period. They had the timing down, the reactions down. So you didn’t want to interrupt what they were doing.

HULLFISH: There were also a bunch of great edits that I call “answer cuts.” The idea of a transition between scenes where the end of one scene calls for something that’s the beginning of the next scene.

CHEW: I think that’s a really good term. I hadn’t heard that term before, but I understood immediately. And it’s exactly the kind of thing that you want as a transition. Some of them were written into the script and some of them came about in the cutting room.

During the early part of my career I would learn things that later on I could apply, and transitions was one thing that was always really important to me as I learned how to use those because much of how things are written in those days – scenes with beginnings, middles and ends – and sometimes playing a scene all the way until the end would kill the momentum of the story moving forward. So when you get out of it earlier and get into the next scene, you have that momentum. So I think answer cuts are one way to do it.

HULLFISH: That’s awesome. One of the things I’ve been talking to people about — and I know it has a negative connotation — is shoe leather. Sometimes having someone going from one place to another and having somebody walk or drive there is literally shoe leather to be deleted. But other times it’s very critical for the audience to get into a new place or to have a breather or something. And in My Favorite Year, there’s a scene where Swann and Benji go to Brooklyn to see his parents. And we actually watch them drive there. What was the purpose of that and why did you decide not to just cut to them knocking on the front door and the uncle opens the door?

CHEW: Several reasons. First, it’s a period picture and you want to be able – wherever you can – to reinforce that notion of its period-ness. It was important there, since the majority of the picture is interiors, that whenever you have a chance to use an exterior you should. I agree with you — shoe leather in many cases interrupts the momentum of the story. But in this case, we wanted to establish period, and the difference in the neighborhoods because we’re mostly in Manhattan where everything is glitzy and we wanted to show them in a period car, driving into a residential neighborhood in Brooklyn. Also, it was a set up for later –when they came out to be greeted by neighbors — so we needed to show early on that it was nighttime and everybody was inside their homes, which contrasted with the end of the scene when our guys were bombarded by fans. In this case, the location did matter.

CHEW: Several reasons. First, it’s a period picture and you want to be able – wherever you can – to reinforce that notion of its period-ness. It was important there, since the majority of the picture is interiors, that whenever you have a chance to use an exterior you should. I agree with you — shoe leather in many cases interrupts the momentum of the story. But in this case, we wanted to establish period, and the difference in the neighborhoods because we’re mostly in Manhattan where everything is glitzy and we wanted to show them in a period car, driving into a residential neighborhood in Brooklyn. Also, it was a set up for later –when they came out to be greeted by neighbors — so we needed to show early on that it was nighttime and everybody was inside their homes, which contrasted with the end of the scene when our guys were bombarded by fans. In this case, the location did matter.

HULLFISH: I want to ask you one more question about My Favorite Year: one of the most emotional scenes in the movie is not played in big close-ups like you might expect. It’s a scene where Benji is confronting Swann about his failures and how scared he is of doing this live TV show.

CHEW: When you work with an actor like Peter O’Toole, even though he may not have dialogue, he gives such interesting performance in reactions.

The story is not just about him but his relationship with Benji and because of the fact that they are major characters that have to confront each other and be honest with each other. We felt that it would have cheapened it by using close-ups because that would have been too obvious to do. So we wanted to give it air and let it breathe on its own and let the actors have their own timing. So that’s why we chose to play a lot of that – like you noticed – in the wider two shots because it is about the relationship between those two.

HULLFISH: Let’s talk about a very funny cut in the movie. A joke that you made as the editor — or maybe it was scripted — I don’t know. Anyway, there’s a scene where Peter O’Toole accidentally goes into the ladies room and a woman says, “You can’t come in here! This is for ladies!” and Peter O’Toole looks down at his privates and says, “So’s this. But every once in a while I have to run some water through it.” Then, with perfect timing — as if the answer to a punchline, you cut to a close-up of a hot dog as it’s being slathered with mustard.

CHEW: That is a good example of something that I came up with in the editing room. This was my first studio feature on my own and I found a really great working relationship with a first-time director like Richard Benjamin, but also with the writer Norman Steinberg. Norman wrote very punchy dialogue with a period style of humor and he did design many of the transitions but that one — when I assembled the scene for the first time —it was really flat. It cut to a generic wide shot of the hot dog stand and it occurred to me to suggest the hot dog cut. They were still shooting at the time, so it was easy for them to pick it up. They all loved the end result. I didn’t even realize how much they loved it until I saw the My Favorite Year DVD with the director’s commentary. Richard Benjamin talked about that joke specifically.

CHEW: That is a good example of something that I came up with in the editing room. This was my first studio feature on my own and I found a really great working relationship with a first-time director like Richard Benjamin, but also with the writer Norman Steinberg. Norman wrote very punchy dialogue with a period style of humor and he did design many of the transitions but that one — when I assembled the scene for the first time —it was really flat. It cut to a generic wide shot of the hot dog stand and it occurred to me to suggest the hot dog cut. They were still shooting at the time, so it was easy for them to pick it up. They all loved the end result. I didn’t even realize how much they loved it until I saw the My Favorite Year DVD with the director’s commentary. Richard Benjamin talked about that joke specifically.

HULLFISH: And that specific close-up of the hot dog had not been shot and you requested it from the editing room?

CHEW: Yeah.

HULLFISH: That’s awesome. Let’s talk a little bit about I Am Sam. The beginning of that movie starts with a series of very tight close-ups. You’re in close-ups for a while. Do you remember if there was other coverage and why you chose to start with those close-ups?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z_AguDqCBvo

CHEW: Yeah. The opening wouldn’t have had as much of an impact if we used the looser shots that were certainly shot. But the notion behind this was several-fold. One was to establish a cutting style that if we start with that and we wanted to use it later, it wouldn’t be surprising. It would be within the grammar that we established for the picture. And two, we wanted to reveal the character through his hands rather than his halting speech or how he moves his head and his eyes — Sean Penn specifically worked on his hands and how his fingers would handle things. In every scene, he was very controlled in terms of how he portrayed the character. And he came up with how he would do that by how he would arrange the sugar packets because that would be a revelation pf one aspect of his character — that he is trying to work for perfection in one area while realizing his imperfections in other areas. In this case, it was within the realm of his world to be able to control that. So we wanted to show on a microscopic scale what his mindset was.

HULLFISH: I liked it because I felt like it gave you an insight into the character without the prejudice seeing him as a mentally retarded or autistic person.

CHEW: Right. We wanted to hold that back.

HULLFISH: As you said, those opening close ups are part of the grammar of the film and you also continue that with jump cuts that you start using early and use throughout the film. There’s a series of jump cuts as Sam leaves the Starbucks at the beginning of the movie.

CHEW: He’s walking to the hospital because the mother of his child was about to give birth. The jump cuts were talked about during pre-production.

When I was interviewed for the job, Jessie Nelson, the co-writer, and director said that in her previous film, she was criticized for being too sentimental. In this case, she purposefully hired Elliott Davis as DP to shoot in this hand-held, erratic fashion because she wanted to have a visual style that would slice against the sentimentality that the picture could be accused of having. Here she wanted to be much more spontaneous, by having the camera operator, in this case, the DP, respond to the moment. And knowing how Sean Penn could be — unpredictable from take to take — this was an approach that she, as the director, consciously made. So we wanted to establish this feeling early on since this is what we’re going to do later. That’s why we loaded it up at the beginning, and when would you introduce that style if you don’t introduce it at the top?

When I was interviewed for the job, Jessie Nelson, the co-writer, and director said that in her previous film, she was criticized for being too sentimental. In this case, she purposefully hired Elliott Davis as DP to shoot in this hand-held, erratic fashion because she wanted to have a visual style that would slice against the sentimentality that the picture could be accused of having. Here she wanted to be much more spontaneous, by having the camera operator, in this case, the DP, respond to the moment. And knowing how Sean Penn could be — unpredictable from take to take — this was an approach that she, as the director, consciously made. So we wanted to establish this feeling early on since this is what we’re going to do later. That’s why we loaded it up at the beginning, and when would you introduce that style if you don’t introduce it at the top?

HULLFISH: Tell me about that unpredictability of Sean Penn. As an editor, is that something that is useful, or is that a curse?

CHEW: Well, it’s a blessing and a curse. It’s a blessing because it worked well with Dakota Fanning who was in her debut film at the age of six. So Sean, being a director himself, knew that he wanted to work with this young actor in a way that didn’t seem stilted. Also, he realized that he was going to be working with some mentally challenged actors, and that had its own unpredictability. When I started looking at the takes, I thought, “This is pretty cool that each take is unique because different things would happen.” Some of the non-actors would step on his lines or there would be action that would happen spontaneously, and that was great because I’m always looking for his response, so the blessing is that I got to cut a Sean Penn film because I think he’s one of the brilliant people on the screen these days.

The curse, of course, is the lack of continuity. I came out of documentaries in the 60s and early 70s and we were always striving to create the illusion of continuity because the stuff that I shot was in the cinema verite style — unstaged real life happening —and we wanted it to not appear jumpy by creating the illusion of continuity. Here, in this case, I’m working against that. I’m cutting together stuff from different takes but connecting them through their having the same emotional value. So the curse of it was not being able to match anything, which means once I decide which take to use, then I’m committed to that because, in another take, he might be in a completely different part of the room, facing a different character. So you had to worry what trouble that choice is going to lead to down the road.

Sean’s actions led Michelle Pfeiffer to break out of her accustomed way of working because she had to listen and respond to Sean. So what Sean did was like dominos. Once he fell a certain way everybody else had to follow.

Sean’s actions led Michelle Pfeiffer to break out of her accustomed way of working because she had to listen and respond to Sean. So what Sean did was like dominos. Once he fell a certain way everybody else had to follow.

HULLFISH: There’s a couple of beautiful montages including the one that leads up to Dakota asking about whether her mom’s going to come back and why her dad is different. Were all the montages shot or scripted to be montages, or were they built from deleted or shortened scenes?

CHEW: They were kind of a blend. In some cases, there were whole scenes that we condensed into montage and in some cases, they were meant to be montages, like Dakota getting older on the swing. That was designed so that each time we see her she would be a year or two older. But I love that solution of cutting down or condensing by montaging it. It’s a way that — you know they used to say if you can’t solve it, dissolve it? – So in this case, if it’s too long, just montage it. It’s also kind of a counter choice of the jump cuts because the montage softened it up, just as the jump cuts gave it an edge.

HULLFISH: There are some interesting choices in the early Dakota scenes of where to play a scene dry and where to add music.

CHEW: Once we realized that by and large we were committed to Beatles music, even though it wasn’t clear where we’d used those songs, the authenticity of Dakota’s performance, especially in those coffee shop scenes, demanded that they be played straight, without the need for support from a music cue.

In the early scenes, we felt that we wanted to have the truthfulness of Dakota as the daughter and Sean as the father reacting to each other. And Sean — it was just so beautiful to watch his dailies, because he’s an established actor and he’s performing with this six-year-old girl who has never been in a movie before, and he was just so in the moment. So we didn’t want to rob the pureness of what they were doing. The second coffee shop scene where they go Bob’s Big Boy instead of IHOP, — that waitress was a day player. How she reacted to Sean’s takes — it took her aback. She didn’t know what was coming next. Nor did the extras reacting to Sean getting louder and louder and out of control. In the editing room, those moments were just gold.

In the early scenes, we felt that we wanted to have the truthfulness of Dakota as the daughter and Sean as the father reacting to each other. And Sean — it was just so beautiful to watch his dailies, because he’s an established actor and he’s performing with this six-year-old girl who has never been in a movie before, and he was just so in the moment. So we didn’t want to rob the pureness of what they were doing. The second coffee shop scene where they go Bob’s Big Boy instead of IHOP, — that waitress was a day player. How she reacted to Sean’s takes — it took her aback. She didn’t know what was coming next. Nor did the extras reacting to Sean getting louder and louder and out of control. In the editing room, those moments were just gold.

HULLFISH: Another movie you used jump cuts in that I loved was Shanghai Noon. There’s a scene where they’re smoking the peace pipe.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qnvpoxOX-2Q

CHEW: The scene only had one punch line and we wanted to get to it sooner. Jackie gave us so much silliness before the punch line that we condensed the scene to just a couple of beats. And we didn’t have useful coverage of his fellow actors to help further the scene.

HULLFISH: Talk to me about your use of fight sound effects. Obviously, in a movie with Jackie Chan, you’re going to have some fight scenes. I always felt like sound effects have such a big impact on the way the rhythm of a scene feels. Do you feel when you’re editing those together that you need to add the sound effect so you have the sense of that rhythm or are you cutting purely visually?

CHEW: In that case, I was cutting purely visually because Jackie has such a specific rhythm for each of his stunts. So I’m talking about the bar scene – the big tableau where he has a fight with like, everybody in the room. It was intriguing for me because other than Star Wars I’ve never cut another action picture. So this one, I wanted the assignment because I was intrigued by the physical comedy of Jackie Chan who reminded me of the things that I used to love of Buster Keaton, but in his case, he would apply it to martial arts. And I thought, “I’ve got to get in on some of this!” He’s very specific with his fight team. He has a whole choreography team that works with him. So that bar room scene, once he walked through the set with his team, they would discuss which locations, which parts of the set they would use, which props they would use, how they would line up the stunt guys. When they shot those, he was very specific. The director gave Jackie control over all of the fight scenes, whether they were in the woods, the river, the barroom, wherever. Also, Jackie got to choose the takes that he thought were good and he was really economical.

Even though he might do nine or ten takes, he would only print like 3. We were shooting on film on that movie and he was very disciplined about that. He narrowed the choices down, so in the editing room we didn’t — as most people do these days — have to go through 10 or 12 takes. We would just have three. After a fight scene was shot, he would send his stunt captain into the cutting room who would look at the three and say, “Oh, Jackie would like this one.” This guy has been working with Jackie long enough to know, so it was really easy for me then because the choices were made really by Jackie. I then had the freedom of how to stitch it together.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=btTcpXDT99s

HULLFISH: I’m interested in your choices of shot sizes to allow the audience to see and understand the geography of the fight instead of playing things so much on close-ups.

CHEW: Part of action-fight scenes like that is that you have to see the feet as well as his whole body movement. Also, we had the luxury of having several set-up scenes staged to establish that set. In these earlier scenes you are made aware of where everybody was, so when Jackie’s character moves around the room during the fight, you had already seen these locations. In order to convey what he was doing, we would stay away from close-ups. I know the tendency in modern films is to see reaction close-ups constantly. But in Jackie’s case, it’s the style to show the choreography.

HULLFISH: There’s an intercutting of a montage of Owen teaching stuff to Jackie intercut with a discussion between Owen and Jackie’s new bride. Then there’s also intercutting between the Carson City fight of Owen with the gun duel, then Jackie doing the fight with the horseshoe on a rope.

CHEW: With the intercutting between what we call the Cowboy School or Cowboy Camp and Owen talking with Jackie’s bride, that is all made in the cutting room. You might write stuff for Owen, but he’s such an instinctive actor that he inhabits the character. He does the IDEA and the INTENT of the dialogue but what makes him such a charming character is that he finds his own expression of it. He starts riffing. So that scene on the log, he starts riffing and the camera was left running to record it all. In Cowboy Camp, Owen and Jackie were just basically trying to crack each other up. Our job was to find the moments that we thought were the funniest by rearranging them and cutting them in pairs or triplets and intercut them with the scene of Roy flirting with Jackie’s bride. It was an editing room exercise.

Oh, the horseshoe fight intercut with the duel. That was written to be intercut, but in such a way that it was very general. Since Roy’s voiceover was off-screen, it was easier to manipulate. More difficult was to split up how Jackie dispatched each bad guy, then intercutting those moments with the duel, where Roy was trying to avoid drawing his gun. So again it was an editing exercise.

Oh, the horseshoe fight intercut with the duel. That was written to be intercut, but in such a way that it was very general. Since Roy’s voiceover was off-screen, it was easier to manipulate. More difficult was to split up how Jackie dispatched each bad guy, then intercutting those moments with the duel, where Roy was trying to avoid drawing his gun. So again it was an editing exercise.

I want to jump back to the scene in the jail cell: when they forged a bond. The big thing in this movie and some others I’ve worked on is: When in the movie – in the course of the running time of a movie – do you bring together the main characters? Because in some films your main characters don’t meet until maybe a half hour in, 40 minutes in, 50 minutes in. Perhaps you’ve introduced them each singly at the top of the picture. Well in this case – in Shanghai Noon – these two characters kind of meet, but in adverse circumstances on the train in the first 15 minutes of the film and then they are separated. If you’ve done your job as a storyteller to establish a likeability in each of these characters so that you as an audience feel invested in Roy the cowboy and in Jackie, this Chinese warrior — if you feel invested in them and they are separated, then the task is “OK. When do you bring these guys back together again? Because I want to see what they’re going to do when they come back together.” So that was a challenge for us.

A good example in an early cut of the film is after that scene on the train when the bad guy releases the logs and the logs roll off that one train car separating Roy from Jackie, and you see the locomotive carrying Jackie away. Well, there was originally a whole sequence of Jackie realizing he’s on a runaway locomotive— I understand it cost a million dollars to create — as the locomotive heads toward the edge of a cliff, we build up the suspense of “Can Jackie stop the locomotive?” It was a four to five-minute sequence. And it was exciting. But ultimately it didn’t add anything to the story moving forward because all we saw was Jackie in his own dilemma. Same thing with Owen’s character. There was a whole scene of how the other guys in his gang turn against him and bury him in the desert up to his neck and it was hilarious. But we had to cut out that pair of scenes so that we could accelerate when those guys would come together again.

A good example in an early cut of the film is after that scene on the train when the bad guy releases the logs and the logs roll off that one train car separating Roy from Jackie, and you see the locomotive carrying Jackie away. Well, there was originally a whole sequence of Jackie realizing he’s on a runaway locomotive— I understand it cost a million dollars to create — as the locomotive heads toward the edge of a cliff, we build up the suspense of “Can Jackie stop the locomotive?” It was a four to five-minute sequence. And it was exciting. But ultimately it didn’t add anything to the story moving forward because all we saw was Jackie in his own dilemma. Same thing with Owen’s character. There was a whole scene of how the other guys in his gang turn against him and bury him in the desert up to his neck and it was hilarious. But we had to cut out that pair of scenes so that we could accelerate when those guys would come together again.

Of course, they come together again in the bar fight and end up in jail. Then the task was how to have them open up and learn to trust each other. Jackie did this wonderful thing where he didn’t really understand some of Owen’s improvisations. He was a little puzzled. So he became really stoic because he didn’t know how to react to Owen’s riffing and Jackie would miss some of his lines and it was a mess to edit. And what I wanted to preserve was Jackie Chan’s resistance to warming up to Owen. So I played as long as I could with Chan not giving in to Owen and then at the same time I was trying to find all those moments of Owen where he’s trying to get Jackie to break-down, because he realizes this was kind of a game between them. He is trying to win over Jackie so that was really wonderful for me to try to stretch that time, because early on they met under different circumstances and now they need each other. So how do I bring them together here by their interaction? That was another scene that I had a lot of fun cutting because those guys were so funny.

HULLFISH: And it was probably heavily improvised. That sounds like it’s kind of Owen’s style.

CHEW: Right. Exactly. That was what this pairing was about and it worked for those characters. Here’s a guy with noble intentions that doesn’t understand English very well and then the other guy is a charming con man saying whatever to get what he wants. It was really a great pairing.

CHEW: Right. Exactly. That was what this pairing was about and it worked for those characters. Here’s a guy with noble intentions that doesn’t understand English very well and then the other guy is a charming con man saying whatever to get what he wants. It was really a great pairing.

HULLFISH: I’ve had that issue myself of “How do we get the two characters becoming playful with each other?” You do the editor’s cut and you see that it takes 45 minutes for the main characters to meet and you think, “It’s really got to happen in like 20.” How long do you wait before you finally get them to meet? And it’s not the same as in the script.

CHEW: That’s typically what editors have to figure out because in the script the writers need to flesh out everything which is the job of the script because, with the screenplay, you’re trying to attract actors to do the film – so you want to give them as much red meat as possible. But then when you get into the cutting room, you realize some scenes are character shoe-leather. You don’t need extra stuff because you want to bring A and B together.

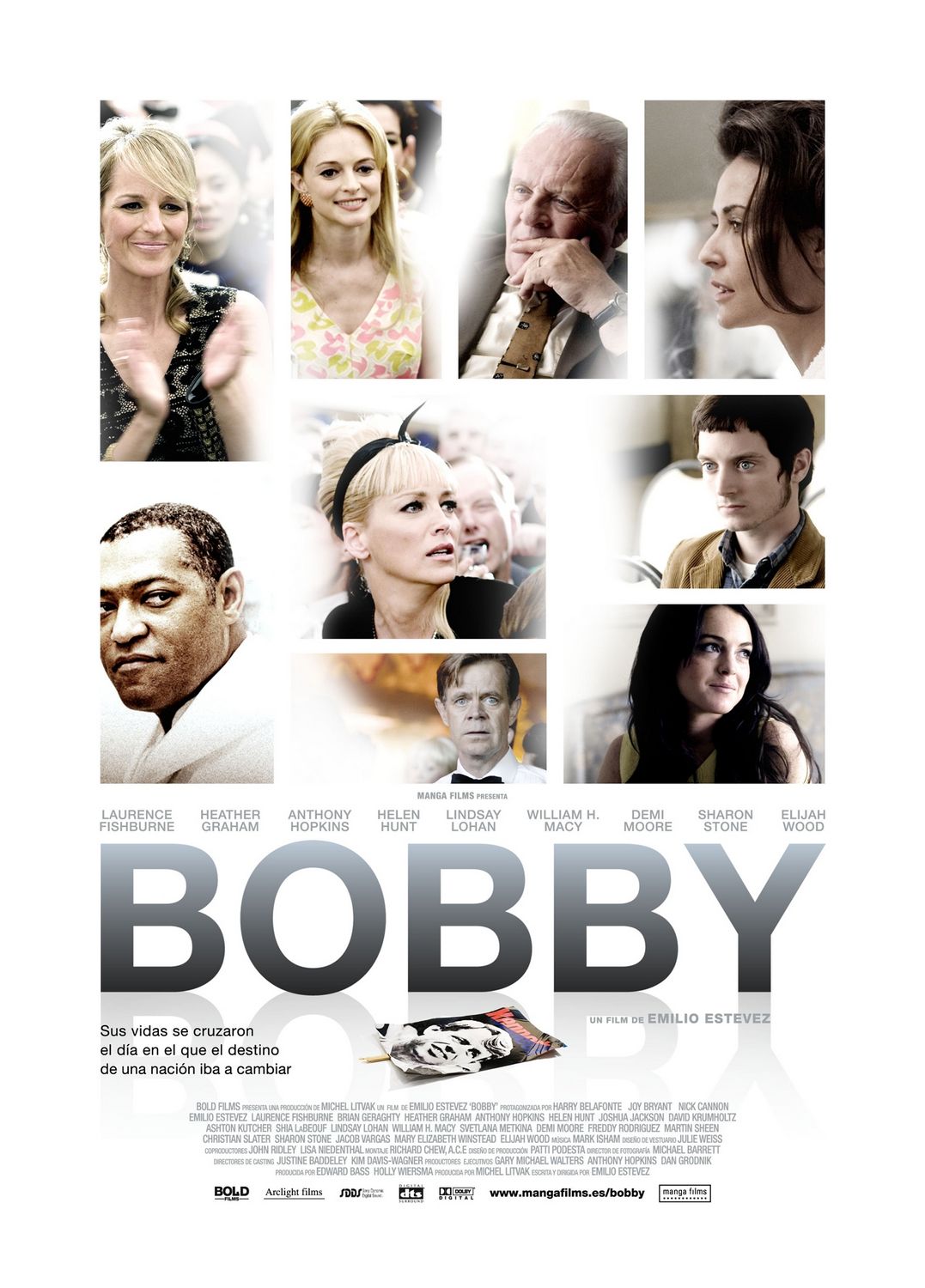

HULLFISH: Let’s talk about Bobby for a little bit. You said you started as a documentary guy and one of the interesting things I thought was your use of a documentary section where Bobby goes to a coal mine. Most of the film – for those who haven’t seen it – is scripted dramatic stuff with actors — with a huge cast of great actors — but occasionally you’re cutting to actual footage of Bobby Kennedy. So what I noticed about that was — even though it was news footage — you made it very cinematic.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=dakDA3bY_6E

CHEW: The backstory involves Harvey Weinstein coming in to take control of the picture. That in itself makes an interesting story and I’m going to take you there then we’ll come back around to your question. Emilio Estevez, even though he’s an actor, he’s really a writer at heart.

HULLFISH: And he also directed this film.

CHEW: He was writing scripts in his 20s, even before he became known as an actor. The first film that was made out of one of the screenplays was at about the same time that he was acting in Repo Man and Breakfast Club. So he was writing screenplays back in his 20s that got produced. Anyway, in this case of Bobby, he wanted to do a film about the assassination of Senator Robert Kennedy, in the style of Grand Hotel from 1932, but he did not want to make the picture solely about Kennedy. He wanted to make a movie about all these other characters who were going about their lives like we all do, then they become entwined by this horrific act.

In the script, Bobby is introduced in the third act, first appearing when he comes into the Ambassador Hotel and Anthony Hopkins’s character greets him. That’s how the movie was shot. So the times when you see a television set in various hotel rooms – what was on the TV sets was stuff that was going on that day that did not anticipate Bobby Kennedy. It was just exercise videos, kids cartoons, cooking shows or something like that. So those were in our early cut of the picture. We didn’t have enough money to really finish the rest of post because we had music to license and a lot of documentary footage to purchase. The picture needed an influx of cash.

Harvey Weinstein saw the picture. Loved it. And he, being a Democratic supporter and a friend of the Kennedy family that goes way back, he said that he would distribute the picture and he would pump a lot of money into it to help us finish it. But it came with a proviso: finish it the way he liked. So he both helped the picture and he hurt the picture.

In seeing it the other day in preparation for this interview, I realized that some good things would not have occurred if it weren’t for his ideas and some things became worse – so it was a strange reminder that he was a blessing and a curse. One of the main things that was positive of what he contributed was — this was in 2006 — He said most of the people who will see this film were born after Kennedy was assassinated. They have no idea who Bobby Kennedy is, so we had to establish up front what the times were like and who this character was that we’re going to be mentioning later. He wanted an attention-grabbing prologue to the film.

In seeing it the other day in preparation for this interview, I realized that some good things would not have occurred if it weren’t for his ideas and some things became worse – so it was a strange reminder that he was a blessing and a curse. One of the main things that was positive of what he contributed was — this was in 2006 — He said most of the people who will see this film were born after Kennedy was assassinated. They have no idea who Bobby Kennedy is, so we had to establish up front what the times were like and who this character was that we’re going to be mentioning later. He wanted an attention-grabbing prologue to the film.

He hired a guy to do this trailer-like opening, but I wanted to do my own so Emilio and I worked to put together that three or four minute montage to establish the times and Bobby, so that by the time he’s mentioned by one of our characters in the film, we would know who he is.

Additionally, Harvey insisted that we replace all of the programs that were on TV with news clips about Bobby Kennedy or his campaign ads so that his presence persisted through the picture until he appeared in person. So then we had to find more archival footage of him and do the visual effects of putting him into the TV screens, so by the time we get to the sequence you originally asked about in Appalachia, seeing how poor the people are, that was, I think, the first time he was really full screen. We gave him like a minute and a half. I made some cuts in that original news footage and did some of that voice over in the style of a news film where he’s actually being interviewed and then we cut away to some later footage of him going into the schoolhouse or homes of people using his voice over and coming back to him finishing the interview. So it was a little more movie-like I suppose. But we had to find a place for it because we didn’t have a slot for that originally. Eventually, we inserted it after the scene where Nick Cannon – the black campaign worker – was lamenting how they’ve lost Dr. Martin Luther King and now Bobby’s the only hope. Somehow we always found a way to address Harvey’s notes.

The other area which he insisted on which I’m not sure helped the picture was to cram in as much pop music from 1968 – as if this would make more convincing that these characters are in that time. To do this, the music supervisors worked tirelessly submitting songs. First Emilio would like it then it had to be played for Harvey’s approval then we would put it in and find out that it was too expensive and we had to take it out. So there was a whole dance around what music to use. I’m not sure it really helped because the background track got to be so busy.

HULLFISH: I didn’t know that backstory so one of my questions was going to be about how you paced the Bobby stuff so that it kept him alive throughout the movie.

CHEW: So you’re saying that you found it useful.

HULLFISH: Honestly, for me, I did find it was useful because I was expecting a movie called Bobby to be about Bobby. I think that without it, I would be getting antsy as an audience member that I came to see a movie called Bobby and where is he?

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=I95Ln53TM1g

CHEW: Harvey’s input really changed the tenor of the picture in so many ways including the closing credits. The song is sung by Aretha Franklin and Mary J Blige. Originally, Emilio and I had cut the closing credits over the funeral train that carried Bobby Kennedy from New York through Washington D.C. to the Arlington Cemetery. What was moving about that was all the people that gathered at the train stations and along the train route, waving or paying tribute to Robert Kennedy. Harvey made us replace it with a montage of photos of the Kennedy family including John and all the brothers and so on, so it became like a tribute to the Kennedy family. It was crazy for us because it wasn’t something that we agreed with but it did provide the funding for us to finish the picture.

HULLFISH: Your version certainly sounds better to me. It sounds similar to Clint Eastwood’s American Sniper. After Chris Kyle gets killed, the end of the movie is his funeral procession. That’s how the movie ends. It’s real footage. It’s not recreation. I can see from that movie how powerful it could be. Bobby came out years before American Sniper.

There’s a great match cut between the fictional ambulance being loaded with Bobby’s body and a real ambulance from news footage of it being loaded.

CHEW: Because of time pressures I had to cut together that whole sequence with just the staged production footage and then, as archival footage came in piece by piece by our researcher Deborah Ricketts, I had to find places to insert them. So the archival shot of that came in at a different time – long after I had put together that sequence. So it was kind of an odd way of working.

HULLFISH: The sound and editing and pacing as Bobby starts to head toward the kitchen — where people old enough to remember know he was going to be shot — as soon as you see that he’s going to a hotel kitchen you know what’s going to happen.

CHEW: That was the first time I had to put together something like that where everybody knows something’s going to happen. It’s almost like a horror picture – like Jason’s going to come out of the closet -but WHEN is he going to come out of the closet? So you try to throw in some curve balls. That’s why we used that point-of-view of looking at all the people in the kitchen. So you’re wondering when Sirhan Sirhan is going to come out — When he’s going to pop out. Between Emilio and me there was a constant discussion of, “OK. Do we do it here? Delay it a little longer? Do we do it later?” It’s kind of a balance between misdirection and then finally revealing it. Because I know the picture so well, I feel like we made it too long. But constantly cutting to the hands and to the welcoming expressions of the kitchen staff and the campaign workers that are in there and the anxiety of some of the other characters who had gotten separated from each other by the crowd. It was a balancing act.

CHEW: That was the first time I had to put together something like that where everybody knows something’s going to happen. It’s almost like a horror picture – like Jason’s going to come out of the closet -but WHEN is he going to come out of the closet? So you try to throw in some curve balls. That’s why we used that point-of-view of looking at all the people in the kitchen. So you’re wondering when Sirhan Sirhan is going to come out — When he’s going to pop out. Between Emilio and me there was a constant discussion of, “OK. Do we do it here? Delay it a little longer? Do we do it later?” It’s kind of a balance between misdirection and then finally revealing it. Because I know the picture so well, I feel like we made it too long. But constantly cutting to the hands and to the welcoming expressions of the kitchen staff and the campaign workers that are in there and the anxiety of some of the other characters who had gotten separated from each other by the crowd. It was a balancing act.

Now originally we had a temp score in there by Hans Zimmer from The Thin Red Line. And it was that same kind of a long sustained low note of dread — a drone. In The Thin Red Line, the cue was used before the soldiers went into battle and that was kind of our underlying temp track, which really worked well. So, when Mark Isham came in and did his version, he created the same kind of tension that I think helped a lot.

HULLFISH: Speaking of music, there’s a great use of the song “The Sound of Silence” — you know “Hello darkness, my old friend, I’ve come to talk with you again” and you pull all of the production sound out. It’s really important the exact moment you decide to spot that cue, right?

CHEW: That was such a major moment because when I was first putting together the scene and Emilio was still shooting, I looked at the actual archival footage of Bobby’s speech and it was not a memorable speech. As is typical of these campaign victory speeches, he thanks everybody. Basically, that was the crux of his speech. He acknowledges all his campaign workers in California by name and then at the very end he says something like ‘Let’s go on and win  Chicago,’ referring to the Democratic presidential nominating convention. So that was the only thing of substance that he said that we could use. So I told Emilio, “I might cut the speech.” And he said, “Well what are you going to do?” I said, “I’ll play it for you when you get here.” I don’t remember what I used originally, but I intercut his appearance at the podium with some of the footage from Vietnam because I wanted to use visual images that were implied by the substance of his words. So instead of hearing him talk about bringing soldiers home or the carnage of the war in Vietnam or the civil unrest over it and civil rights, I would just use images of those events intercut with him at the podium and the images would suggest to the audience the content of what he was talking about. I forgot what music I was using over that, but when Emilio finally saw what I was putting together he came up with the idea of using The Sound of Silence. And the first time I looked at that song with the images it brought tears to my eyes. Later we fiddled around with how early or late the cue started.

Chicago,’ referring to the Democratic presidential nominating convention. So that was the only thing of substance that he said that we could use. So I told Emilio, “I might cut the speech.” And he said, “Well what are you going to do?” I said, “I’ll play it for you when you get here.” I don’t remember what I used originally, but I intercut his appearance at the podium with some of the footage from Vietnam because I wanted to use visual images that were implied by the substance of his words. So instead of hearing him talk about bringing soldiers home or the carnage of the war in Vietnam or the civil unrest over it and civil rights, I would just use images of those events intercut with him at the podium and the images would suggest to the audience the content of what he was talking about. I forgot what music I was using over that, but when Emilio finally saw what I was putting together he came up with the idea of using The Sound of Silence. And the first time I looked at that song with the images it brought tears to my eyes. Later we fiddled around with how early or late the cue started.

HULLFISH: What a great story. I love that! That was a fantastic moment. Obviously completely created in editing.

CHEW: Yeah, that’s a good example when the collaboration between a director and editor works.

HULLFISH: Yeah, the fact that that wasn’t your original music choice is really interesting. Emilio was the writer and the director and that presents its own challenges because sometimes you hear about writers being very precious with their work and other times when writers realize that the editing process is part of the writing process.

CHEW: Yeah I think that’s the case for sure. Emilio appreciated my contributions as an editor because he realized that I understood what he was striving for and that I could accomplish with imagery what he was trying to accomplish with words. So, in that case, it was a really fruitful relationship. That’s why we’ve continued to work on several other projects since then because I think he realizes I can illustrate through imagery and juxtaposition of imagery, the intent.

HULLFISH: Let’s talk about Risky Business. There are a lot of POV shots in Risky Business.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3JXcqzJjHf0

CHEW: That’s part of writer-director Paul Brickman’s humor. Early on, particularly when Joel’s friend Miles says, “Every once in a while, Joel, you have to say ‘what the f*ck.’” Originally we just stayed on him as he walks into the kitchen and his mom and dad are talking to him about his SAT scores but gradually we shift to his point of view only. I thought that was really kind of clever. That’s the way Brickman shot it. I didn’t have any other coverage so that was really bold for a first time director– not shooting coverage and with only one approach. First, it was Joel’s point of view of his parents at home, then when they go to the airport in the car. And then when they are driving to the airport. And then finally we reveal Joel in the airport waving goodbye. So that was designed. A lot of those angles were shot as written — like him pouring himself a scotch and putting a Coke into it afterward. And for the sake of film lore, the scene where he slides in in his socks, the screenplay scripted him dancing to that specific song.

HULLFISH: There’s probably a half-dozen or more POVs.

CHEW: That was part of his signature style for sure. That was a great experience because of how open he was to the ideas that I brought in to help the picture in certain areas. And I guess that’s the case with any good collaboration between an editor and director.

The train sequence is probably one of the best examples that I can tell about creative collaboration. Originally, in the script that sequence was described in just a few sentences. Very simply as something like “Joel and Lana enter the turnstile. They board the train. They make love in the car into the night.” Something like that – which is general language suggesting the circumstances without detail. On location, number one, Paul shot a version of it that was not complete. Number two, the footage did not have the eroticism that he felt it should have. It was a series of studied, artful compositions. However, there was some second unit footage that he had shot of trains in different sizes that he intended for establishing shots.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TDlTGhe3YoE

So while he was shooting in Chicago and I was editing in LA, it occurred to me that what he was intending was to have a sexual climax but we didn’t have that. Besides, you can’t really show that in the 80s. I thought maybe we could do that by inference, so I put together a sequence with the second unit coverage of train pass-bys. I constructed it exactly the way that we now see it in the final picture, intending it to be like the sexual climax. I showed it to Paul and he really liked the idea. Then he set about to write a sequence that could precede it, to lead up to the visual climax. Months later he was able to shoot the front end of the scene where Joel and Lana would enter the train, but he added obstacles once they got on the train. So even though they were horny, they had to wait and get all these people off the train first. With that new footage, we built more tension into that scene and end with that homeless guy that wouldn’t leave. That’s vintage Paul Brickman: to find a silent gag like that so he could delay the payoff.

This was still back in the days of film and we didn’t have the luxury of using digital enhancement. When we started putting together this sexual part of it, I thought that the way we viewed the characters could be much more mesmerizing if we step-printed it to create an illusion of time slowing down. In those days when you come up with optical effects it took a day or two to do because you have to make a dupe of the original workprint and send it to an optical house where they have to shoot it a certain way and after they develop it at the lab, they send it back to you as a black and white print, not even in color. And then you would cut it in and maybe the frame rate doesn’t quite work, so you make some adjustments and send it out again to the optical house. Then they repeat their work cycle.

Luckily I had an assistant who figured out mathematically which frames to be printed how many times, with the idea in mind that if we changed gradually the motion, the action would eventually become more sensual.

We got enamored with this one two-shot side angle of Lana and Joel where they were in the throes of sex. It didn’t work if we cut away from that angle, so Paul wanted to join several different sections of that same angle together. That would have made a series of jump cuts, and we did not want jump cuts, which we thought was an abrupt and hard-edged transition for an erotic moment. So I came up with this idea: since we established earlier how the lights go out on the elevated train when it changes tracks, let’s use the idea of the lights dimming momentarily and coming back on. So I thought we could connect these shots of the same angle without apparent jump cuts by just using a short fade to black. In this fashion, we could use all these different takes without a jump cut.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-POVHvk01XI

For music in the first part of the sequence, Paul had specified in the script playing the Phil Collins song, “In the Air Tonight”. We did use that, but we wanted to find a more erotic musical cue for the second part of the scene. Now it happened that one of my assistants was playing a track of Tangerine Dream out of his boom box down the hall. When we heard its mesmerizing looped percussion, we thought it would add to the eroticism of the scene and laid it against the picture. Boom. It became clear that’s exactly what we needed.

HULLFISH: Maybe you could provide some wisdom on cutting dialogue and when to be on the speaker and when to be on reactions.

CHEW: In deciding what to do, you may want to consider whether you’re furthering the narrative, or helping a performance, or changing the rhythm. In Cuckoo’s Nest, we were furthering narrative by cutting to reactions. In other instances, you may cut away from the speaker to substitute other dialogue or delete lines. And for style’s sake, you don’t want the dialogue to always dictate the cut. I like to use pre-laps sometimes to lead you into the next cut or hasten the pacing. Also sometimes I use a post-lap in order to see the reaction of the listener before she speaks.

HULLFISH: I think there are great examples of reaction shots in I Am Sam. The moments you chose to show reactions seemed so organic and natural. People need to realize that the reaction shots are very intentional choices of when to cut to them and exactly what that reaction is.

CHEW: Right. Exactly. You have to dig relentlessly through the material to realize, “Michelle (Pfeiffer) did this here, but this may be more interesting to place it over here.” Of course, you don’t want to rob the performer of what they’re doing either because obviously, they work really quite hard to plan their reaction over a particular part of the scene. And you don’t want to take away from what they’re doing, so you have to do this very judiciously out of respect for the performer. So yes, sometimes you do take a reaction that happens in one spot and use it elsewhere in the scene.

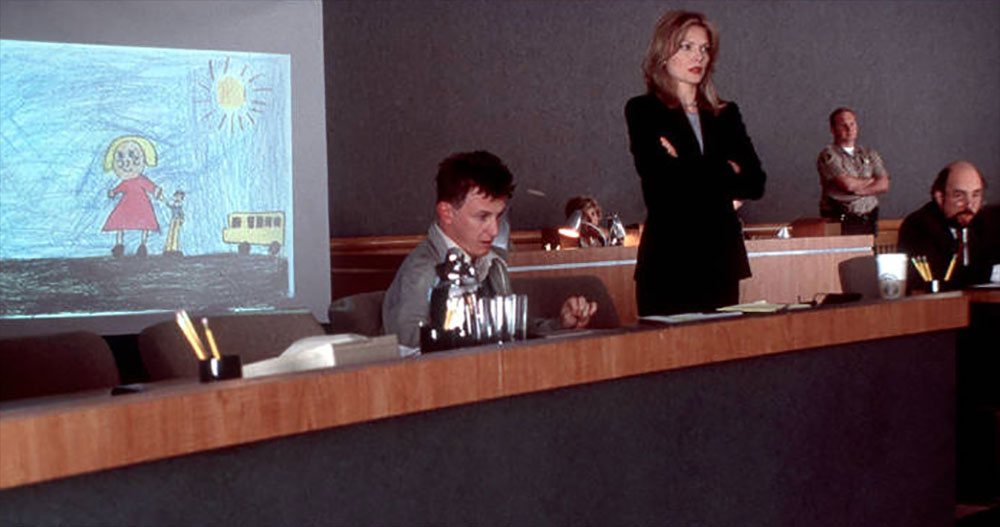

In the courtroom, it’s so talky between Richard Schiff as the prosecuting attorney, and Michelle as the defense lawyer. It was really important to help the audience track how each of those characters are responding to Sean Penn’s testimony.

In the courtroom, it’s so talky between Richard Schiff as the prosecuting attorney, and Michelle as the defense lawyer. It was really important to help the audience track how each of those characters are responding to Sean Penn’s testimony.

I know that you were a little surprised that I didn’t really want to talk about One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest or The Conversation, but I’ve realized after looking back over a long career that those were films that were basically like going to film school for me. In The Conversation, working with Walter Murch particularly allowed me to learn how to restructure movies, how to restructure scenes and storytelling. In the case of One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, learning from Milos Forman how he used reaction shots, especially in the group therapy sessions. All these other characters came to life, even though they had no lines, by how we used their reactions and where they were placed. It was invaluable for me to absorb that lesson and apply it later to films like I Am Sam, namely that reaction shots really help you further the storytelling and they’re not merely throw-aways to cover jump cuts. That was how I thought of reaction shots when I was working in documentaries. In old-school documentaries, you’re trying to preserve the illusion of real-time continuity by hiding jump cuts through inserting reaction shots.

HULLFISH: There’s a couple of great reaction shots that I can remember from I Am Sam off the top of my head when Michelle is cross-examining the psychologist and then she brings up the overdose of her son. You don’t need to be looking at Michele when she says that.

CHEW: Right.

HULLFISH: Another one is when Michelle goes to Sam’s house and he’s built that weird wall of origami birds. He goes off on her saying that people like her couldn’t possibly understand what it’s like to have problems. I found new respect for Michelle Pfeiffer watching that scene.

CHEW: Her character had to make a transition at some point because she is so unsympathetic.

There’s another scene in I Am Sam I want to point out. After the courtroom scene, that one where Sean’s character falls apart in a series of rapid cuts of different angles, there’s this scene of separation, where the social worker takes custody of the child played by Dakota Fanning. It’s a hallway scene silhouetted against a blue exterior. As the editor, I felt it didn’t work because of the histrionics. And here I’m working with Jessie Nelson, the director who wrote the scene as well. It was so painful to hear the emoting of all the participants, that I tried replacing the dialogue with a music cue. The cue was kind of neutral — not laden with emotion — but kind of wacky. It was done by an Australian band called Penguin Cafe Orchestra. It was off-center and not sentimental. And it took away, for me, the curse of the over-the-top nature of the emotion in the scene. It was hard for me as an editor to explain to the director/writer, “Hey, this scene that you directed and wrote, I took all the dialogue out.” That was really a hard sell, but when she looked at it she realized it played better.

HULLFISH: Did you have a cut of it the way she had originally written it first?

CHEW: Yes, but as I recall I showed her first the scene with music only. After she recovered from the shock of that, I showed her the scene with original dialogue.

HULLFISH: For me, I had a similar experience which was one of those things that was a painful early lesson as a young editor: if you have a radical idea like that, show the director what they want first. But for you, as a more experienced editor, you maybe had a bit more latitude?

CHEW: Yeah. I felt I could show her something radical because there were other things I did that she liked. If she’d hated everything I did prior to that, then, of course, I would not have shown it to her without her dialogue as the first viewing.

HULLFISH: That’s an interesting commentary on the editor as psychiatrist, and what kind of social engineering you have to do as an editor.

CHEW: It is learning as an editor what your place is in the cutting room, and where you are in the larger scheme of things. It’s taken me many years to learn this because I worked in documentaries, where there wasn’t as much of a hierarchy, at least where I came from: a lot of independent docs first in Seattle, and then eventually in San Francisco before I came to Hollywood.

So I always had an ego as an editor. Feeling that I worked really hard on a particular sequence and coming up with “something so cool that don’t you dare f*cking change it!” Not realizing that I’m only part of a team. It took me a long time to realize that I’m just one person on a film that had some awesome ideas contributed by all these other people on the set!

Editors tend to value our own ideas more highly perhaps because we work in isolation. We’re not on the set usually. We’re not caught in the cacophony and chaos of it and not experience what a director experiences in getting barraged constantly all day about how to shoot a scene.

As an editor, I feel like, “Hey, I’m the king on this throne in here because I spent all this time in examining all the footage and this is the way it should go together.” It’s taken me a long time to learn how to step away from that stance; to realize gradually that I’m just here to contribute to the mix of ideas and hopefully my idea is a good idea that could be used, but it’s not the only idea.

Sometimes I give scenes to my assistants to cut and after seeing their defensiveness in reacting to critical comments, when I see that coming from someone else, then I realize that I might be doing this too when a director doesn’t like what I’ve done. That’s hard, I think, for younger editors especially to absorb, to understand that we editors got to learn to roll with it.

Lee Smith, who won the editing Oscar for “Dunkirk” — a very well-deserved Oscar for him — in his acceptance speech after he thanked the director, Christopher Nolan, he said something like, “Thankfully, he doesn’t actually handle the equipment,” leading me to suspect that Nolan was in the editing room looking over Smith’s shoulder, like many directors, dictating almost every cut even though they’re not operating the keyboard. So I think that editors by and large understood Lee Smith’s quip,, sympathizing and agreeing with him, that thankfully, a director values his editor and leaves us space to make our own contributions wherever we can.

Lee Smith, who won the editing Oscar for “Dunkirk” — a very well-deserved Oscar for him — in his acceptance speech after he thanked the director, Christopher Nolan, he said something like, “Thankfully, he doesn’t actually handle the equipment,” leading me to suspect that Nolan was in the editing room looking over Smith’s shoulder, like many directors, dictating almost every cut even though they’re not operating the keyboard. So I think that editors by and large understood Lee Smith’s quip,, sympathizing and agreeing with him, that thankfully, a director values his editor and leaves us space to make our own contributions wherever we can.

HULLFISH: I’m really interested in your transition from Moviola, or whatever you used before Avid. And what did you bring with you to digital editing from the days of film editing.

CHEW: Well one thing that I retained from film editing was how I had the dailies organized for me, so I can work with them. In the days when I worked on the KEM flatbed I would have assistants group the dailies in a certain way that helped me evaluate the footage and I retained that system when I moved to Avid. I was surprised at how quickly — once I made the switch to digital — how quickly I could retrieve things, make cuts, but I found it didn’t help with the decision making process. It didn’t help me with coming up with an idea. It was faster if I were more literal in my cut to assemble scenes the way they were written and the way they were shot, no doubt. But I think most editors value coming up with the idea — that there’s a light bulb that comes on and the light bulb doesn’t come on because you can do things faster. Having a nonlinear editing system like the Avid enables us to do things faster but that doesn’t enable us to come up with something that’s really cool or good or better. I like the distance I had when I was working in film because it took me longer to do something, like maybe retrieve a film trim still be hanging in a trim bin or rolled up in a box and I’d have an assistant find it, and in the meantime I’d have this downtime to examine whether in my mind I could come up with a better solution.

When you do stuff in an almost instantaneous fashion — almost out of a gut reaction — you might not have the time to evaluate what you’re going to do or how you’re going to do it. So this last film that I did with Emilio Estevez – I had my assistant — who I promoted to being a co-editor — work with him in putting it together the way Emilio wanted. In another room, I worked on what I considered the problem areas — of course in consultation with the director. I wanted to work on transitions and areas that needed refining in a different way. I was kind of playing in my own sandbox. Emilio was working in a certain direction to conform the film to what he intended when he wrote it, while I’m trying to get the film to work in areas where I thought, “Oh, we need to increase tension here, so let me try this or that.” Inspired ideas can sometimes come to you when you’re allowed the time to tinker with it. So I would say that’s probably the thing that I miss when working in film as opposed to now working in non-linear.

HULLFISH: You mentioned the method that you used to organize dailies on film is the same as it is now. What is that method?

CHEW: Nothing special. Like on film, I’ll have all the preferred takes within one camera set-up attached back to back. So say for scene 68, set-up A, I would have preferred takes 3, 4, 7, and 9 joined together. That was in the “circled-takes” days where the director on the set would “circle” preferred takes. In those days I didn’t look at the B-negative footage (the stuff not chosen to be printed). So it worked really well for me to study the three or four circled takes for that camera set-up on their own timeline. And the same for 68-B and 68-C and so on.

HULLFISH: What’s an editing story from Star Wars that you have?

CHEW: One thing is how George Lucas, having an editor’s instincts, created an air battle sequence intercutting German, Japanese, and American fighter planes from World War Two archival footage. That was the first thing he showed me, even before the dailies. I joined the picture after it returned to America because he shot the picture in England where he had another editor working on it for awhile but he fired him. When he got back to America he hired Marcia Lucas, me and then later Paul Hirsch. He showed me some early dailies and assigned to me my first sequence to cut, what he called the gun-port sequence, which is when Han Solo, Luke and the gang all jumped onto the Millennium Falcon to escape from the Death Star. As they flew away, they were attacked by T.I.E. fighters. It was shot as a blue screen sequence where all our characters are sitting in a cockpit or gun-port against blue screen backgrounds. George needed me to put a scene together so that ILM could start working on adding the attacking T.I.E. fighters on the blue screens. I had no idea what he wanted because I’m looking at footage of these guys whirling around in their chairs looking up and out into the blue screen. To help me, George showed me his air battle sequence that I just talked about. I loved his earlier films like THX-1138 and American Graffiti, but not until I saw how he cut together the air battle from this old footage did I realize what an editor’s eye he had. He was masterfully leading the eye with each of his cuts. So after looking at a couple of minutes of that, I understood. That was a huge guide for me. so very instructive.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cAETMbLPBw8

Based on that, I was able to weave together a cut of Luke and Han’s interaction. They were like two schoolboys playing together in a sandbox, shouting to each other warnings of what to do. Cutting on the rhythm of their dialogue and circling moves in their chairs, I’m leading the eye here and there with these cuts. Into this medley I added the Princess and Chewbacca, each turning to look this way and that, knowing that George will have ILM create streaking aircraft in the blue screen space.

The other story requires the reminder that we were fabricating this film in the pre-digital age. One assignment that George gave me was to indicate on the workprint which laser gun was shooting and which direction the shot would go. So I was given all these assembled scenes of stormtroopers shooting at our heroes. Using a grease pencil on the workprint, I would mark which gun was shooting, and the direction of the laser beam across the screen. What’s the duration of its travel? Is it in one frame or two or three frames going across the screen? Then the return shots had to be detailed out the same way, and I was fastidiously going frame by frame marking with grease pencil the exchange of the gun battle. When I eventually played it back for George, it was really crazy to see the barrage of these laser shots. The grease pencil made exaggeratedly big marks on the film frame because I’m drawing onto a small 35mm frame. When projected, the laser guns looked like cannons shooting cannonballs across the frame! It became so silly to see all these grease pencil marks crisscrossing all over the screen.

HULLFISH: Interesting that he asked you as an editor to do that because of the pacing and the eye direction that those laser blasts would cause.

CHEW: Right. And I would mark where the explosion would be with a little star! “Oh, it landed here!” Here’s a little asterisk. He needed that as a guide for the visual effects crew at ILM. He would constantly shuttle material between the cutting rooms in San Anselmo and ILM in Van Nuys.

HULLFISH: Last question. What was the first feature film you cut on Avid?

CHEW: Waiting to Exhale in 1995.

HULLFISH: Awesome. Richard, thank you so much for the generosity of your time. I really appreciate this and I think my readers will as well.

CHEW: Thank you very much for your patience and your hard work in researching your questions. Have a great day.

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish

To read more interviews in the Art of the Cut series, check out THIS LINK and follow me on Twitter @stevehullfish

The first 50 interviews in the series provided the material for the book, “Art of the Cut: Conversations with Film and TV Editors.” This is a unique book that breaks down interviews with many of the world’s best editors and organizes it into a virtual roundtable discussion centering on the topics editors care about. It is a powerful tool for experienced and aspiring editors alike. Cinemontage and CinemaEditor magazine both gave it rave reviews. No other book provides the breadth of opinion and experience. Combined, the editors featured in the book have edited for over 1,000 years on many of the most iconic, critically acclaimed and biggest box office hits in the history of cinema.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now