In the motion graphics world, it is easy to become seduced with technology. New releases of software and hardware bring with them the promise of being able to achieve previously unimaginable feats. But at the end of the day, we don’t deliver a spec sheet to our clients; we deliver art – and hopefully art that effectively communicates the ideas they want to get across.

You know where to learn about gear; where do you learn about art?

This article was written in 1999 after visiting the BDA (Broadcast Designers’ Association) conference in San Francisco. The BDA is dedicated to those who create graphics-intensive imagery such as station identities, openers, and commercials as well as print, web, and set designs. In 1999, grunge type treatments were still all the rage; it’s fun to look back now and see what from those designs still looks fresh and relevant, and what looks dated and odd. We’ve posted a companion article which includes focuses on specific studios and jobs.

During and after the show, we had the opportunity to sound out a number of design studios on their approaches, what they felt the current trends were in both design and technology, and how this affected their work. The most prevalent idea was that good communication is often subtle and holistic, rather than focusing on one image or catch phrase which is supposed to bang the viewer over the head with The Message. And yes, your choice of tools can help you more easily realize your art.

Balancing Elements: Typography

The talks that appealed to us most were hearing designers talk about design. For example, typography is a bedrock element of most motion graphics. Some of the best designers came from the type and print worlds. A significant portion of the books in our own library focus on type. But it is surprising how many video people are uncomfortable manipulating type – especially when it comes to properly integrating it with other elements.

In one of the more entertaining talks, BDA Master Series speaker David Carson wasn’t reluctant to skewer sacred design cows, including BDA’s own logo and brochures. Declaring that “Seven (the unsettling film opening title that influenced graphic design for years) is over; it’s time for something new”, Carson chided practitioners of the currently popular visual-overload look, where there is no unused space in the frame and everything is blurred and jumpy. Instead, he advocated simplicity, white space (or its equivalent), and in general that Less is More. For example, he feels what made the “typing” commercials he created for Lucent so memorable was that they were an island of calm inbetween so many frantic ads.

Simplicity does not necessarily mean obviousness: “Don’t mistake legibility for communication,” Carson warns. His own designs are marked by words, icons, and even the company logo crowding the edges of the page or screen, often with difficult to read text. “Give your audience some credit; they’re intelligent” – and can not only figure out a partially hidden message, but might also enjoy connecting the dots themselves. Taken to an extreme, another Masters series speaker – Neville Brody – even showed the Fuse fonts where the “characters” are often just suggestive of a letter’s shape.

It was surprising to hear Carson, known best for cutting-edge typography, say it is the image that dictates to him what the type should be. All the visual elements are then equal in importance, rather than trying to make the viewer focus on one. As a result, it frustrates him greatly when a client changes just the photo, and keeps the type the same: such as changing an image of a girl enjoying learning to a serious-looking boy, or replacing an otherwise enabled person in a wheelchair with an able-bodied person in a normal chair. The overall subliminal message being conveyed is compromised.

Design by Belief for USA Networks.

This all-elements-are-equal approach is shared by others. Steve Kazanjian and Mike Goedecke, then partners in the Venice, California based studio Belief, feel that they and other design studios “are actually all creators of what we like to call the ‘New Visual Language.’ A New Visual Linguist is someone who feels broadcast design is more than just type and graphics. Motion Design has become an unrecognized art form that revolves around not only type, but mood, color, and sound. It’s about creating televised works of art.”

Some of the most compelling work we saw used type as graphical elements, texture, and even replacements for traditional framing devices and lines, even if the type itself was too small or distantly-focused to read. Rather than being literal, it conveyed the intended emotion. The grunge/nervous movement (not yet dead, and still compelling) has been doing this for a few years now with distressed in-your-face type, but the same ideal can be used in more subtle and elegant ways.

next page: the beginning of the desktop studio trend

Trend: Small Studios; Big Desktops

A large number of the commercials, promos and show openers you see winning awards and airing on television were produced by large agencies in high-end post houses on exceedingly expensive Quantel and Discreet Logic (now Autodesk) video engines. However, one of the buzzes at the show in 1999 was how many larger design firms and post houses were closing down or cutting back.

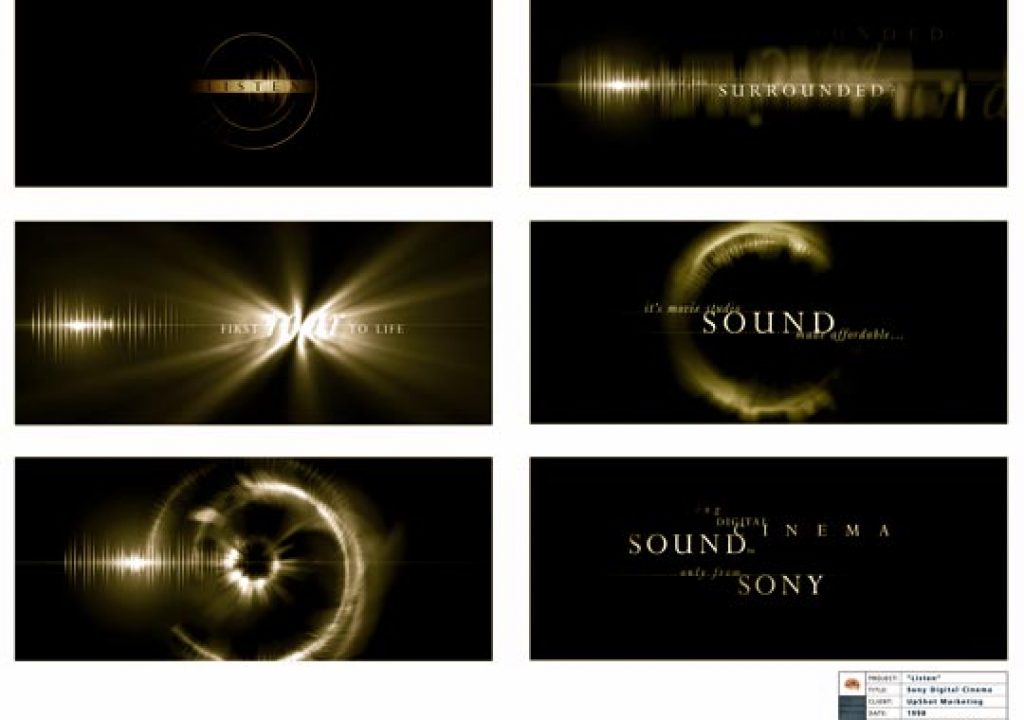

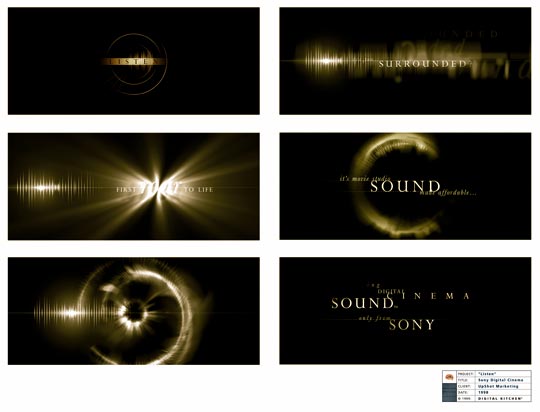

In contrast, the number of smaller, boutique studios was starting to explode back in ’99. Many of these studios are based around designers with their own desktop graphic tools, rather than total reliance on higher-end facilities with megabuck toys. An example of this is Digital Kitchen in Bellevue, Washington. They originally started as a desktop-driven “digital studio/experimentation lab” for ad agency Matthaeus Halverson. After that agency merged with another, founder Paul Matthaeus stayed with DK, which is now a stand-alone entity. Their work splits 50/50 between desktop and higher end tools, listing Adobe After Effects, an Avid Media Composer, and a Discreet Logic Flame among their toolset at the time.

Design by Belief for USA Networks.

This transition is not entirely smooth, as many clients still don’t “get” the desktop revolution, and are more comfortable with more “traditional” methods. Kazanjian and Goedecke of Belief now regularly host a BDA session based on using the Macintosh and other desktop tools. The room was packed this year, but many of the audience members remain skeptical with arms firmly crossed over their chests. However, you couldn’t deny the power of the final work. The tape they played featuring work from The Cab Company, H-Gun, Brian Diecks Design, Digital Kitchen, The Firm, Reality Check, 22 Product, as well as Belief, was extremely compelling and indeed, many of these studios have won BDA awards.

We spoke with a number of studios that had moved to using desktop tools for all or some of their work, trying to get an idea how they were making the transition themselves. Silas Hickey of Sydney, Australia’s Toast commented “generally we will take semi-completed segments – digital files, unmixed soundtrack etc. – to a post house for compositing and audio sweetening.” Lisa Berghout of San Rafael, California’s L.inc also typically finished at the time on a Flame, but notes “as tools such as After Effects continue to expand however, our studio is able to finish more projects on the desktop.”

Design by Brian Diecks for ESPN.

Many studios are moving further along that curve. Jim Deloye of Chicago’s H-Gun Labs comments that “Since H-Gun is made up of designers and animators, we rarely go out of house. Nearly all of our work is finished on the desktop.” They were particularly fond of the combination of a Media 100 editing system with SDI connections to the DigiBeta format: “The image quality is amazing. It will rule the future. Yes.” And where some award winners thanked their Flame operators, Gold and World Class winner Brian Diecks thanked Adobe and Media 100 for creating his tools.

Of course, one of the biggest advocates of the desktop is Belief. “The desktop computer revolution has and will continue to change the face of the motion graphic landscape. These powerful little boxes allow the return of the Auteur.” As opposed to hiding or apologizing for using less expensive machines, Mike and Steve say “We want our clients to know that we do our work on Macintosh computers, and why that’s advantageous to them. You can’t redo a graphic in the middle of the night for something that airs the following morning if you have to schedule time at a post facility. If a client needs to make a slight change, we don’t have to reload the elements into the Henry and then begin working. We can pull up the elements off our hard drives because we own the equipment.”

Rather than being a reason to negotiate a lower rate, Belief (also big fans of the then-popular Media 100/SDI/DigiBeta combination of the day) sees the use of desktop machines as a way to better optimize the existing budget. For example, rather than paying for time in a post house, they use the money to shoot on film instead of video. “A client can come to Belief and say I have X amount of money, what can I do with it? We can then take that money and give them the most bang for the buck. We try to put as much of their budget on the screen as possible.”

Design by L.inc for CNET.

Many also like the control that owning the tools gives them. “By having more creative control, we are allowed more spontaneity and flexibility in regards to production schedules and costs, because we are not completely reliant on outside vendors like post-production companies,” notes L.inc’s Berghout. Hollywood 3D specialists Reality Check likes desktop tools not just for their power, but because “It is really easy to integrate new personnel into our production pipeline,” observes co-founder Andrew Heimbold. “With desktop tools there is generally also a shorter learning curve, as most of our artists are accustomed to working on the desktop. We can spend more time focusing on design and creation of good content, rather than learning new tools.” Belief concurs: “You have to own the equipment you use to create your work, the same way a painter owns their easel and brushes.”

Not that the desktop solution has no downside. Just as video editors who have made the move to non-linear note that the ability to try out more ideas usually means spending more time than before on the same length show, Toast’s Hickey commented that “even with a predetermined idea of the final piece, we often get a sort of option paralysis during the final tweaking of a sequence, checking endless color variations, different levels of contrast and so on.”

next page: working in 2D vs. 3D

New Dimensions: 2D vs. 3D

Motion graphics is usually thought of as a 2D art, with elements coming from essentially flat sources such as video, film, photos, and text. However, computer-generated and 3D graphics have been used since at least the 1970s. And we’re seeing more use of 3D today, especially to create abstract environments rather than just spaceships and dinosaurs.

Design by Reality Check for NFL Today.

Still, not all designers have embraced 3D. A couple of studios we spoke with haven’t really dabbled in it yet. At the other extreme, Andrew Heimbold responds that “Reality Check was formed to raise the level of quality and speed in 3D content creation.” In between, H-Gun’s Deloye is more non-chalant about the influence 3D has on their work: “It’s an aesthetic decision. Or the availability to do 3D presents alternatives to the work in seeking solutions or special executions in the process.”

The software packages most often cited back then were ElectricImage and Autodesk’s Maya. EI was known both for its graphical look and its relatively fast render times; Maya has great strengths in character animation, which is also a hot trend. But almost any package can be used, especially if you are just creating elements – rather than an entire character or world – in 3D.

A frame from Toast’s In Flight Panic for MTV Asia.

For example, Toast’s Hickey used Autodesk’s 3D Studio Max for their portions of their hilarious and multiple-award-winning “In Flight Panic” spot for MTV Asia, which pokes fun at the fear of flying and the emergency procedure cards found in seat backs. “We primarily used 3DMax and found it perfect for this type of job. For example, a fight sequence was accomplished by roughly animating the figures with pencil, scanning the animation, and projecting those scans as an animated background template. We used this template as a guide to position the 3D mannequins, which were rendered with the Max ‘Illustrator’ plug-in to emulate the smooth technical style illustrations displayed on a typical flight safety card.”

Whereas Hickey sometimes tries to make 3D look like flat illustrations, Brian Diecks used 3D tools to give some dimension to otherwise flat art. In his award-winning spots for ESPN International, “A lot of things started in Illustrator: numbers, names of countries, globes and a few maps. Most of these elements were then taken into a 3D environment and given some depth because we didn’t want it to be a flat plane. The fact that they’re spinning and drifting adds another level of complexity and keeps things moving.”

Design by H-Gun for Meat Beat Manifesto music video.

Of course, not all 3D or character animation must be realized in the computer. Toast also used 2D cel animation and claymation on their ‘In Flight’ sequence; H-Gun has worked with miniatures and “360 degree dead time filming” using 40 Nikon F-4s with remote trigger rigging to circle around real objects frozen in time and space. And on the flip side, not all 3D must be for video – for example, beyond-the-edge design studio The Attik uses their 3D skills to create mockups of product packaging for their clients, in addition to print and video work.

Technology and Art

“Belief is a studio that is based on the art of design, versus the technology of design” proclaims Kazanjian and Goedecke. “This paradigm shift is a state of mind that distinguishes us from the larger black box post houses.” Indeed, at the end of the day the technology is a tool (or a paintbrush) that you learn to help you realize your art.

following pages: two points of view

Subtext and Context: 3 Ring Circus’ State of Design ’99

Elaine Cantwell and Jeff Boortz, then with design studio 3 Ring Circus – who won 12 awards at the 1999 show alone – hosted one of the more thoughtful talks at BDA. Entitled “State of Design in ’99”, their seminar emphasized that its not what font you chose or what scene you filmed, but how they all work together. “The purpose of design is to enhance communication,” they proclaim. “The goal of the Designer is enhanced communication through well-manipulated media.” With that in mind, they presented a series of key concepts, with examples of what they felt were good implementations.

Unfortunately, due to clearance issues, we cannot show you images from the associated spots, but we think you can get a lot out of just the text descriptions:

Relevance

The intended receivers of a message must be able to tell that the message was intended for them.

Clarity

Viewers must be able to “accurately decipher the content of the communication.”

Subtext

“The intended Receivers must be able to deduce the personality, sensibility, and agenda of the Sender by the Form and The Content of the message.” Two of their favorite spots were Toast’s ‘In Flight Panic’ for MTV Asia – a crazed parody on the worst fears of someone who reads one of those flight safety cards (you can see an image sequence from it on the following pages) – and Fuel’s ‘Skechers’ commercial, which reflects the sensibilities of teens rather than overtly tries to sell them shoes.

Strength

The message has got to punch through the noise of all the other spots on TV. This requires creativity, as reinforced by the next point:

Contrast

Off-beat presentations of familiar ideas “are more likely to overcome their context and penetrate the consciousness.” An example is Sandy Fraser’s promos for the Showcase movie channel: Set in a hotel, viewers check into different rooms to watch what they want with others.

Great Ideas

A well-crafted spot that communicates on many levels is more likely to linger in a viewer’s mind. Infinito is a network in Argentina devoted to explaining the unexplainable (UFOs, paranormal, the occult); Telezign’s promos for the network present visual puzzles such as endless loops which reinforces this mystery.

Visual Style

Again, the need to cut through the clutter, either by reinforcing a brand’s identity, or setting a strong, new visual tone – as long as it is appropriate to the piece. For example, for Showtime’s “No Limits” promotion, 3 Ring Circus used strong organic, elemental images such as paint splashing against the screen rather than overly suggestive pictures (which would obviously have limits, being finished works).

Superior Production

Even though the idea must come first, low production quality can take away from the idea. It’s not about having the biggest budget, but about being inventive with the budget. This echoes what presenters such as Belief stated as one of the advantages of owning the desktop tools, rather than renting time at a post house, they can take the money saved and “put it on the screen” in terms of a better live-action shoot, etc.

The Attik: Defining the Graphic Edge

One of the most respected design firms is The Attik, which originated in England and now has offices in the US and Australia. Their work is identifiable for its uncontainable energy, extraordinarily distressed type, and integration of elements from 3D to grunge. In addition to video, they create print work, packaging, music, and documentaries such as “Negative Forces, Witchcraft, and Idolatry”: a 15-minute visual tour-de-force of 24 hours spent in the New York subway (which was screened during one of BDA’s many nighttime parties). Their “brochures” are packaging marvels in themselves, selling(!) in the area of $100 at select bookstores. They don’t need to win awards; their sheer attitude is enough for many.

BDA asked The Attik “to make a presentation that showcases the work of designers from around the world – work that is the Graphic Edge.” In typical outside-the-box fashion, instead of a lecture, they created an hour-long multimedia assault featuring three video projection screens, four Powerbooks, racks of synthesizers, a soundtrack (roughly half of which was performed live) that alternated between soothing and driving, and examples of their work as well as that of others. At intervals during the presentation, text came on screen explaining their own thoughts on definitions and the creative process, with the ultimate message being follow your own lead:

We refuse to judge you or your work based on our definition of the ‘Graphic Edge.’

What is more important is the path followed to express a unique thought.

Do not be afraid of what is along the path.

During the presentation, unnarrated text and visual examples illustrated their own creative process:

CAPTURE

The first is a means to identify and obtain new input.CHALLENGE

We organize input and compare it against preconceived notions.

This is the mind’s natural selection.

We either agree or disagreeCATALYST

We combine the energy of a new idea with complimentary and opposing forces to substantiate its existence and move it to an entirely new place.EXPERIMENTATION

We test modes and validate what we already suspect is true.

In the real world, you may have to deal with clients who have a more conservative idea of what their company represents, or what they think their audience can handle. Noise for its own sake is seldom the antedote for this. But those who can harness their creative energies to explore new modes of communication beyond “the edge” are those more likely to be remembered in the end.

Click here to see the companion article which focuses on nine of our favorite studios at the conference.