I didn’t go to film school, but in asking around, it seems the majority of schools want their students to learn about film history, both from a technical and creative perspective, before they ever get the chance or opportunity to get their hands on a camera. A friend who graduated from the USC film school said the equivalent of a 101 class was more of a film theory and history class. It wasn’t until they took a 290 level course that they were actually able to get their hands on a camera.

This makes sense conceptually, because finding out why the camera movements that debuted in Citizen Kane were so revolutionary, and why Rocky struck such a cord with audiences, is a relevant thing to consider for any filmmaker who is looking to impact their audience in the same manner. Students are naturally anxious to start creating, but as our own Art Adams has said, there’s a hundred years of film history that have gotten us where we are, and it makes sense to learn that history, rather than attempt to gleam such details from experience.

That’s a tough argument to make with young filmmakers who have the tools to start making movies as soon as they get their hands on a smart phone, and it’s the first time students have been in this position. In the past, film students had to wait until a school allowed them to use a camera or editing system before they could shoot or cut anything. Now, that sort of hardware and software is readily available. This new reality has not only changed the expectations of the students coming into these classes, but it’s also changed what they’re looking and wanting to learn. Kids who have been posting videos to YouTube and Vine their entire lives are anxious to start their careers as opposed to learning how to pull focus. Whether or not that’s a good or bad thing is a separate issue, especially because in many cases, they don’t actually know how to pull focus, or what it really means.

I can’t say whether or not the authors of Filmmaking in Action recognized that film students have this desire and need, or simply realized there wasn’t a 101 level book on the market that showcased an all-encompassing look at what it means to put together a film, but one suspects they had an inkling of both concepts. Authors Adam Leipzig, Barry S. Weiss and Michael Goldman speak directly to students of the digital revolution that we’re living in, while also working to give them all of the knowledge and insight they’ll need to hit the ground running with their careers. In doing so, they’ve created a textbook that is unlike anything else out there, which addresses the ways in which young filmmakers want to learn about the logistics of their craft. At the same time, it provides critical insights from experienced professionals around the technical and creative challenges student will encounter as they take a concept into production and through distribution.

I can’t say whether or not the authors of Filmmaking in Action recognized that film students have this desire and need, or simply realized there wasn’t a 101 level book on the market that showcased an all-encompassing look at what it means to put together a film, but one suspects they had an inkling of both concepts. Authors Adam Leipzig, Barry S. Weiss and Michael Goldman speak directly to students of the digital revolution that we’re living in, while also working to give them all of the knowledge and insight they’ll need to hit the ground running with their careers. In doing so, they’ve created a textbook that is unlike anything else out there, which addresses the ways in which young filmmakers want to learn about the logistics of their craft. At the same time, it provides critical insights from experienced professionals around the technical and creative challenges student will encounter as they take a concept into production and through distribution.

The scope of the book is ambitious, because it literally tries to cover everything while taking those concepts and ideas all the way back to their core. Terms like film, editor and director are defined in plain English. I don’t say that as a criticism, especially since they spend far more time explaining terms like hypercardioid and digital intermediate, but as an illustration of how thorough they are with these details. Perhaps that’s far too basic for the generation of students that I just mentioned who have videos that are trending on Twitter, but these are details that will surely not be lost on them. They might have heard about anamorphic lenses, but having such things defined and explained in context is a relevant lesson for them now and throughout their career.

It’s not just the basics that are broken down here though. I was inclined to rip out their page on aspect ratios just so I could have a handy reference that I don’t need to go digging or searching for. There’s also some great insight around detailed concepts like multiple formats, where so many people can get caught in the weeds. There’s plenty of practical advice as well, with classic insight such as “get into a scene as late as you can, and out of a scene as early as you can”. All things that are relevant to filmmakers of every level, for different reasons and in different circumstances.

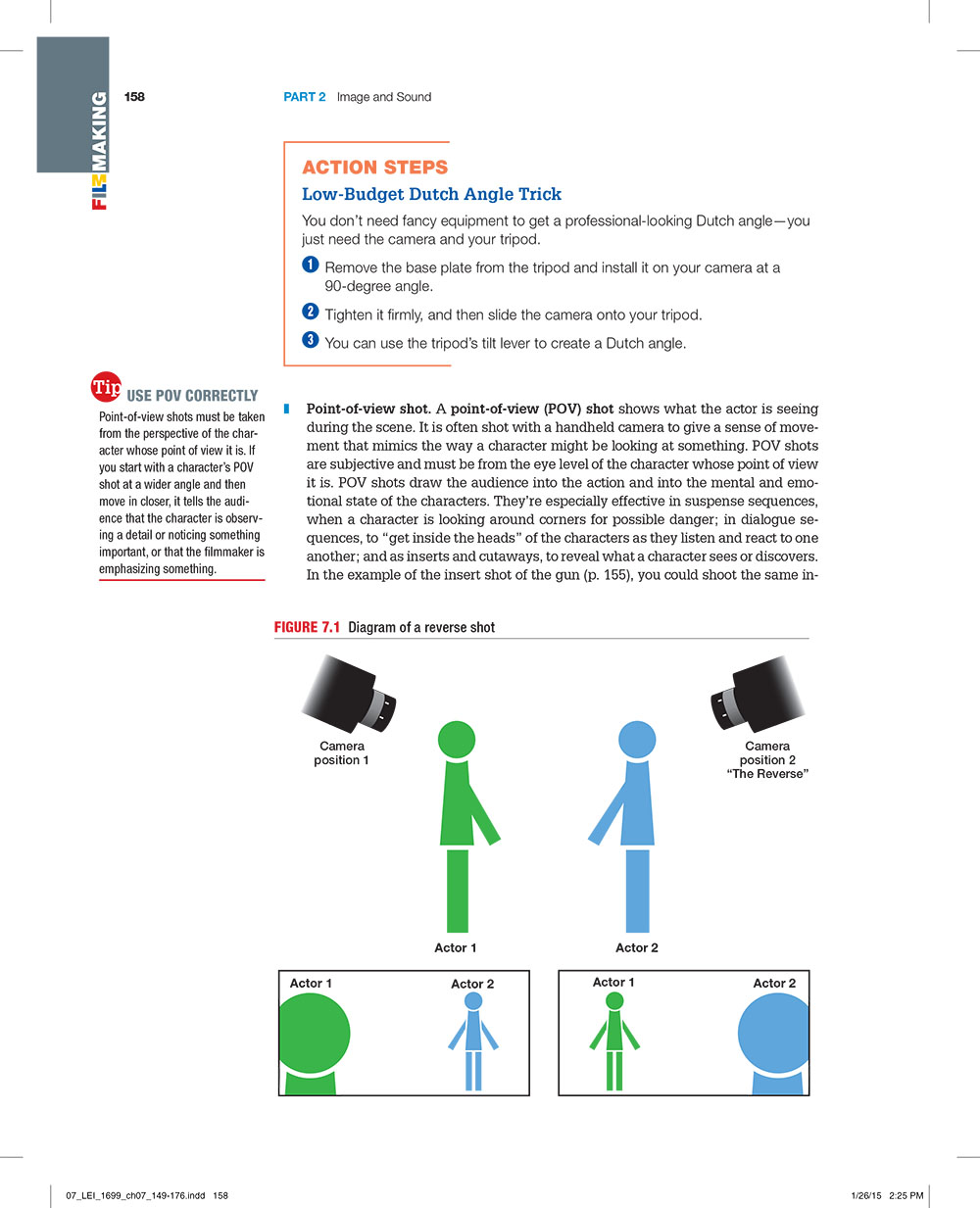

The book is broken up into 15 chapters that cover the pre-production, production, post and distribution phases of a project. Chapters like “Conceptualization and Design”, “Telling the Story with the Camera”, and “Editing Skills” give you a pretty good idea of the info that each contain. The book’s overall focus is around the logistics of what it means to produce a film, which would make you think the emphasis is all about the technical details, but the authors take great care to ensure the book didn’t turn into a tome that was all about production scheduling and telling readers not to violate the 180-degree rule. Two separate chapters are focused on editing, but one was more about the technical aspects of editing, while the other was focused more on the creative aspects of it. The logistics that come into play when doing things like file naming and file sorting are dealt with just as much as exploring the art of putting together a montage.

The book is broken up into 15 chapters that cover the pre-production, production, post and distribution phases of a project. Chapters like “Conceptualization and Design”, “Telling the Story with the Camera”, and “Editing Skills” give you a pretty good idea of the info that each contain. The book’s overall focus is around the logistics of what it means to produce a film, which would make you think the emphasis is all about the technical details, but the authors take great care to ensure the book didn’t turn into a tome that was all about production scheduling and telling readers not to violate the 180-degree rule. Two separate chapters are focused on editing, but one was more about the technical aspects of editing, while the other was focused more on the creative aspects of it. The logistics that come into play when doing things like file naming and file sorting are dealt with just as much as exploring the art of putting together a montage.

Even at a quick glance this kind of scope can be intimidating, especially since every chapter could and do have entire books dedicated to the material they cover. Luckily, the authors do a nice job of separating out each section so they can be dealt with on their own terms. Of course, that’s not how creative productions work, but they make sure to drop in hints about editing considerations when shooting, thinking about marketability when putting together a script, etc. It’s a tough line to walk, but thankfully the chapters aren’t overwhelming or all over the place.

The format of the book helps keep the reader on track as well, since each chapter features multiple lists that break out things like “Planning the Lighting” and “Art of the Trim”. These lists provide students with a concise way to approach the specific tasks in a project with a real world approach. It’s true that every project is going to be different, but giving students a specific place to start is invaluable.

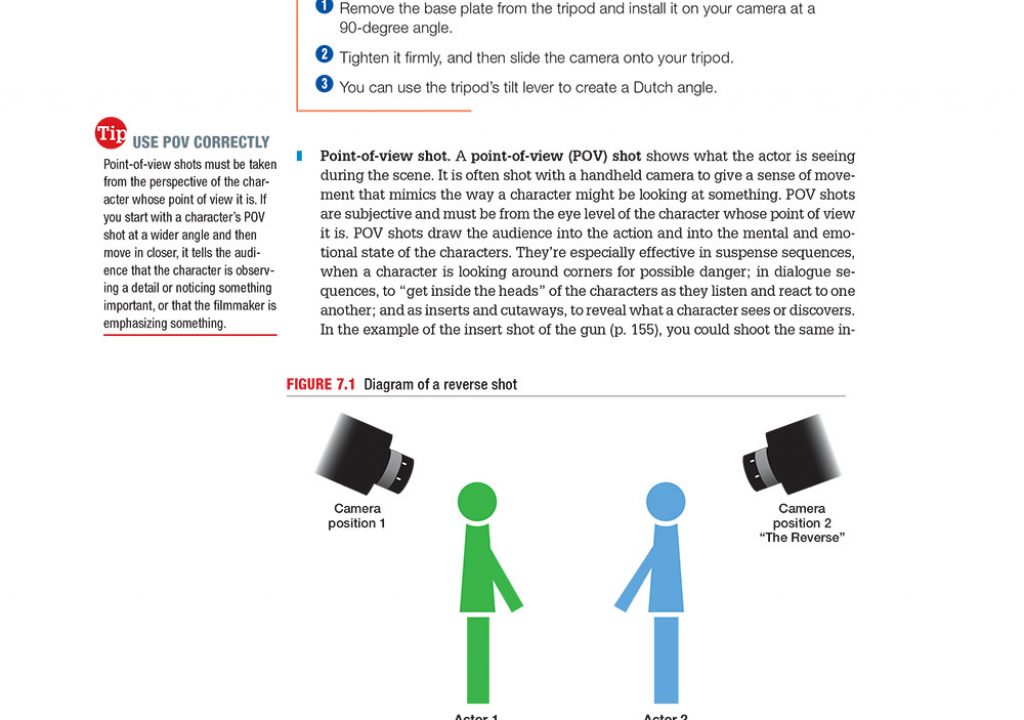

There are also numerous “Tips” and “Practice” sections that fill the margins of the pages, which the authors use to offer additional insights or a practical exercise. Additionally, features like “Tech Talk” and “Producer Smarts” are there to explain the details of native editing and the producer’s role in marketing, and those are just two quick examples. Sometimes these sections took me out of the text of the actual chapter, but the insights here are from real world experiences, and always worthwhile to check out.

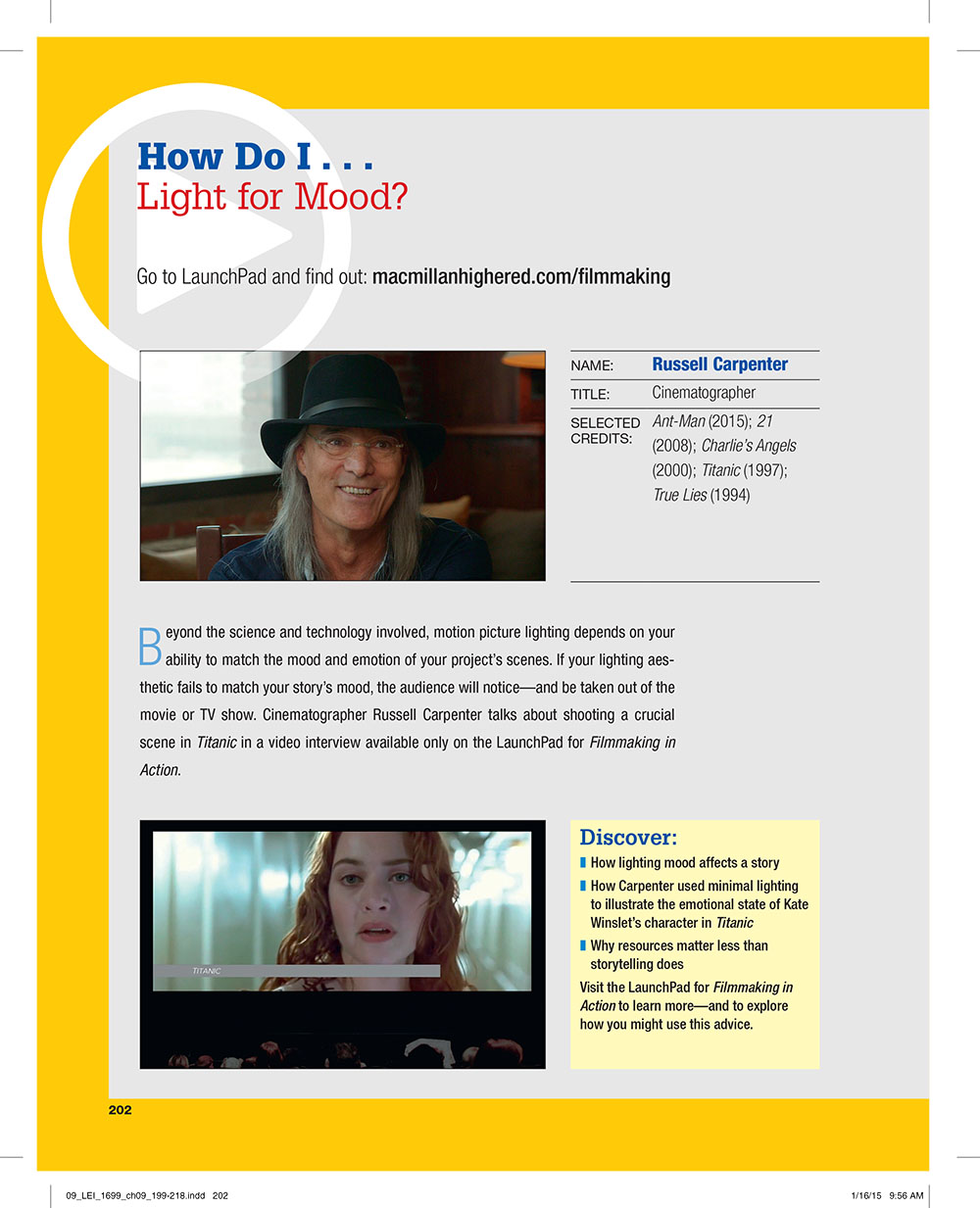

I mentioned how different chapters make it a point to focus on the more creative aspects of a topic, but even then, it can be difficult to speak of such considerations when we’re not being specific. To help with that, every single chapter contains a “How Do I…” section, which features an interview available online with an industry professional to talk through some of the nuances they’ve seen and helped create in their line of work. Whether it’s cinematographer Jacob Pinger talking about preparing the camera, or William Goldenberg explaining how he shows a point of view through editing, or Dennis O’Connor explaining how to market a movie, these features are practically worth the price of the book on their own.

I mentioned how different chapters make it a point to focus on the more creative aspects of a topic, but even then, it can be difficult to speak of such considerations when we’re not being specific. To help with that, every single chapter contains a “How Do I…” section, which features an interview available online with an industry professional to talk through some of the nuances they’ve seen and helped create in their line of work. Whether it’s cinematographer Jacob Pinger talking about preparing the camera, or William Goldenberg explaining how he shows a point of view through editing, or Dennis O’Connor explaining how to market a movie, these features are practically worth the price of the book on their own.

If I had to, I’d say these sections were my favorite part of the book, although each chapter also has these sorts of insights sprinkled throughout. Quite often a chapter will open up with a professional recounting a real-world experience. Finding out why a legend like Walter Murch thinks of sound as a “fabric” can completely change your perspective. The feedback I often get from readers is that their favorite PVC articles are the ones where an author will simply sit back and explain how they were able to do their job, or why they think the way they do about a particular topic or concept. That’s exactly what’s happening when these insights are shared in the text and especially in the video interviews.

Hollywood professionals are obviously working at a far different scale and scope than film students, but the authors embraced this chasm instead of ignoring it or pretending it doesn’t exist. The authors don’t shy away from telling students how things work on a Hollywood film set, but just as often include phrases like “on a student film, your timeline and resources may not make that feasible”. Most students want to end up on those sets, so telling them how things work there while keeping them grounded with the reality in front of them is a great way to have them focused on both the present and the future.

In some ways the book almost had me thinking that you could avoid going to film school and just focus on the info laid out here. After all, it details the process and steps that filmmakers need to go through, all the way from starting with a script to the various ways it can be monetized in distribution. If you have all this info, why bother taking a class at all?

Well, there are various reasons, the least of which is because the authors clearly want you to. With phrases like “ask your instructor” and “class project” sprinkled throughout the pages, along with a number of exercises that are specifically designed to take place in the classroom, this is very much a textbook, and doesn’t pretend to be otherwise. Plus, there are some instances where further clarification from that instructor is going to be especially handy. Hearing the authors say that “the external mic option is often preferable because it provides better sound quality than most built-in mics” is something that begs to be further defined and extrapolated upon by a teacher. After all, in a creative endeavor like filmmaking, results will vary.

I can certainly appreciate a specific focus, but it’s almost odd to see a book which is embracing the changing times in so many ways still be built to work in this one specific setting. On the other hand, showcasing this much info at a 101 level is in and of itself a major change, and the definition of “classroom” is evolving. Regardless of what that evolution looks like, this book would still be a fit for that environment no matter how it is and will eventually be defined, so maybe it has more flexibility than I’m envisioning.

There are plenty of people who would argue that 101 film students shouldn’t be taught or worried about these kinds of details and filmmaking logistics, and that they instead should be taught about film history, and everything else that 100 years of filmmaking has to teach them. And they might be right. But that’s not going to stop the next generation of filmmakers from wanting this info as soon as they can have it, regardless of how better off they might be to take a different approach.

There are plenty of people who would argue that 101 film students shouldn’t be taught or worried about these kinds of details and filmmaking logistics, and that they instead should be taught about film history, and everything else that 100 years of filmmaking has to teach them. And they might be right. But that’s not going to stop the next generation of filmmakers from wanting this info as soon as they can have it, regardless of how better off they might be to take a different approach.

Filmmaking in Action gives today’s students the info they want and plenty more, as it showcases the fact that if you want to work in the industry, you’re going to need to have an understanding of far more than whatever your role might happen to be on a particular project. And I can’t imagine a better lesson for young filmmakers who are fixated on getting their careers going.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now