The BSC’s London exhibition is possibly the first film and TV expo of the year, unless we count the cameras that turn up at the Consumer Electronics Show. The BSC holds its event in Evolution London, which is one of those semi-permanent structures that likes to refer to itself as a blank canvas event space, but which has previously been fairly described as an enormous cryogenic tent. This year, organisers had got the message, and cranked up the heating to the point where the communal vest on the demonstration Steadicam quickly became damp with the combined efforts of a whole host of inexperienced attendees.

Those steps were probably less wobbly than they might have been a few years ago, precisely because the Volt addition to Steadicam frankly makes operating it a lot easier. The system is effectively combines a classic inertial stabiliser with the micro-mechanical gyro technology which makes gimbals possible. It works shockingly well, avoiding laggy gimbal framing while cleaning up the gently wandering horizon of all but the very best Steadicam.

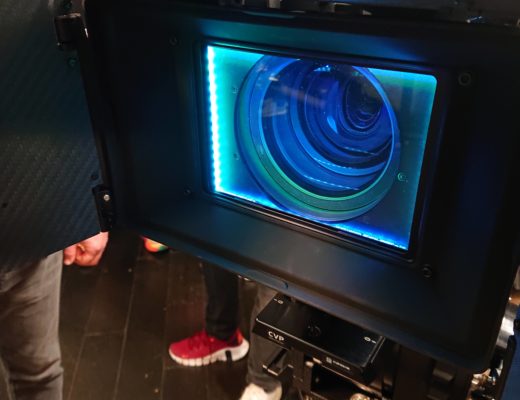

That fusion is perhaps emblematic of a generation of film and TV gear which increasingly combines the established high end with the pick of mass market technology. Sigma’s 28-45mm T2.0 zoom is a case in point. At first glance, it looks exactly as a cinema zoom should, with bold markings, FIZ gears, and construction entirely of machined metal. Even in the hand, it feels like any other member of Sigma’s range of cinema glass. The company showed an early prototype coupled to an FP, which is still one of the smallest, lightest routes to full-frame 4K raw.

Wait, what?

Mount the new zoom, half-press to snap things into focus, and – wait, what? Things do snap into focus, which is not exactly the behaviour we’d expect of a traditional cinema lens. Most previous attempts at this sort of thing have looked and felt too much like a stills lens to satisfy the high end; think of the (older, higher-ratio, slower) Canon CN-E18-80mm T/4.4, which is certainly an autofocus-capable video zoom, but also visibly a product of the company’s stills lens department, rather than its cinema people.

Further, the FP’s L mount arises from Sigma’s founder membership of the L-mount alliance, which has most recently (and perhaps rather belatedly) appeared on Blackmagic’s cameras too. Blackmagic, incidentally, did not announce a new camera at the show, though it hardly needs to: with the recent 12K full-frame options and the still-bleeding-edge 14K Ursa Cine, the company’s R&D people probably deserve a week by the pool. Nikon and Canon, of course, have their respective Z and RF ecosystems to attend to. Canon showed its new hybrid primes and Nikon showed the 28-135 F/4 and the Z mount for cameras built by subsidiary Red.

Both those things represent a very similar meeting of technological ways. All of these things rely on active mounts, which filmmaking inherits from the somewhat less expensive world of stills photography. Of course, at one point, the very concept of autofocus would have brought film and TV people out in a rash; it was Canon which broke that spell. Traditionally, bayonet style mounts have been thought of as too feeble for full-size cinema lenses, but Nikon has also engineered a breech lock mechanism for its ultra-wide, ultra-short Z mount.

People will still scowl at a Z mount for high end work, but respected manufacturers of long standing, such as Zeiss, seem keen to join the party. The company’s Nano Primes (adaptable to various short mounts) could not exist without them, and neither could Fujifilm’s MK series, or Sony’s long-established SELP line, or Nikon’s new contender which seems designed to go head to head with the likes of the Sony SELP28135G.

A blending of ideas

So, does the BSC show prompt us on what to expect for the rest of the year? Only in part. It’s very much built to cater to the high end, and as such attracts both exhibitors and attendees who are perhaps more likely than average to raise an eyebrow at affordable techniques. Still, Fujifilm’s new camera, the GFX Eterna, is more or less a self-rehousing of its medium-format stills offering that’s specifically named after a filmstock; there can hardly be a more deliberate blending of ideas.

Film and TV work has a history of clinging to traditions, often for good reason. It kept shooting film for – probably – most of a decade longer than it really needed to. There is no sign of the incumbents fading. Leitz, for instance continues to enjoy a healthy market for an optical lineup (expanded at the show with a 20mm Thalia) which more or less represents the six-star hotel of lens options. The new circa-5K lighting options from Nanlux and Aputure, discussed recently by the estimable Mr. Cohen, might not exist if there wasn’t a demand from the high end (though they’ll certainly sell in smaller numbers than their 600-watt cousins).

Until we reach the point where AI can generate movies from a tagline, camera equipment will always need to intercept a few photons. Still, as long as that’s the case, we probably shouldn’t be too surprised that the vast R&D budgets of the mass market occasionally come up with things that the high end might find useful.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now