“Man must rise above the Earth—to the top of the atmosphere and beyond—for only thus will he fully understand the world in which he lives.” — Socrates

If Socrates were alive today, he would probably own a drone.

It’s getting to the point where almost everyone does anyway. Okay, a bit of an exaggeration but no one can argue that drones have become very popular very quickly and are suddenly big business. Add the controversy regarding everything from privacy rights to endangering commercial aircraft and it’s hard to find anyone who hasn’t at least heard about drones.

To paraphrase Talking Heads’ song “Once in a Lifetime,” “Well, how did we get here?”

Socrates’ was right. As soon as photography was portable enough, photographers were putting their cameras in kites, aboard balloons and even on birds in order to see a view from above. The first known photograph was taken around 1826. By 1858, Gaspar Felix Tournachon was able to photograph the houses of the French village of Petit-Becetre from a balloon about 250 feet overhead. Those images haven’t survived but two years later, James Wallace Black was able to photograph the U.S. city of Boston from a hot air balloon and the shot is recognized as being the oldest known surviving aerial photograph.

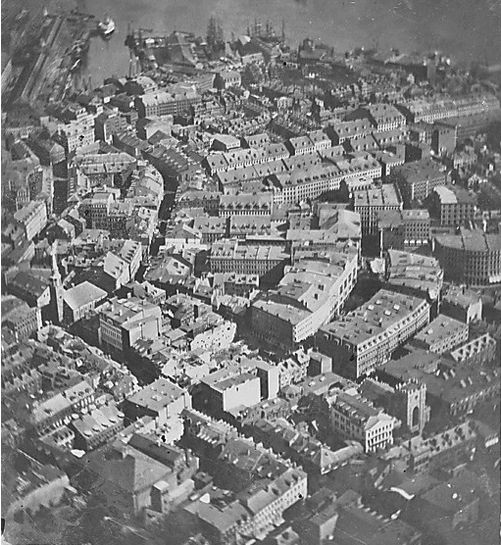

Believed to be the oldest picture shot from the air. this picture of Boston was taken in 1860 using a hot air balloon. From Smithsonian.com

So it would follow that as soon as airplanes came into being, someone would try shooting from a heavier than air craft. Ironically, Wilbur Wright was to become the first aerial motion picture pilot. The Wrights were in Europe demonstrating their Wright Flyer Model A, the first airplane to be offered for sale. The airplane could also accommodate a passenger. Outside of Rome, Italy, on April 24, 1909, with a camera mounted on the left lower wing near the pilot’s seat, the first air to ground motion picture film from an airplane was shot.

The aerial cinematography begins about 2:02 into the footage.

Aerial photography took center attention with the release of “Wings” in 1927. In a 1996 article, “A History of Aerial Cinematography” published in The Operating Cameraman, the magazine of the Society of Camera Operators, Stan McClain describes Harry Perry’s cinematography of “Wings”, as containing “some the most spectacular aerial footage that is still considered to be the best ‘combat’ footage even by today’s standards.” The film went on to win the first Oscar for best picture (it is also the only silent film so honored) in 1929.

Harry Perry with an early aerial mount for the film “Wings.” From A Certain Cinema website by Sergio Leemann

Even while “Wings” was in release, another aerial extravaganza was in pre-production. Howard Hughes’ “Hell’s Angels” hired over a hundred pilots to fly more than 50 aircraft. Hughes spent close to two million dollars to create the biggest war picture ever made.

These films and the many that followed through World War Two were always aviation related with aircraft woven into the storyline. The camera platforms always had to be moving toward or away from an object at high speed unless shooting alongside another aircraft.

All that changed with the first helicopter certified for civilian use, the Bell 47, on March 8, 1946. That same year, “The Bandit of Sherwood Forest” (1946) with Cornel Wilde was released. An item in an April, 1945, Hollywood Reporter noted that a specially designed helicopter with camera mounts in the cockpit was employed to film a scene storming the castle. This would mark the first mention of an aerial camera platform used in a film unrelated to aviation. However, in viewing the film, no such scene exists. In fact, the castle in the released film is a matte painting and the cast only talks about storming the castle but never actually does it. So the first helicopter shot may have been left on the cutting room floor.

Richard Hart, Jr. is President of National Helicopter Service and Engineering Company in Los Angeles and the son of the company’s founder Richard Hart, Sr. National has been a leading supplier of helicopters, helicopter camera rigs and fixed wing aircraft to film and television productions since the early 1950’s. Looking at National’s list of credits one cannot avoid being impressed. The first thing Hart told me was those early mounts for helicopters only “allowed for some re-orientation of the camera for getting different angles.” They did nothing for stabilization. Without stabilization, a camera attached to an airframe experiences high frequency vibrations that show in the resulting film footage.

The Bell 47 became a star in its own right when it was introduced to the public in popular television programs such as Ziv Productions’ “Highway Patrol” (1955-1959) starring Broderick Crawford and later, Desilu Productions’ “Whirlybirds” (1957-1960) starring Kenneth Tobey and Craig Hill with National Helicopter supplying the helicopters and pilots. Bob Gilbreath, Vice President of National Helicopters, appeared in many of the episodes, and in the case of “Highway Patrol,” in the uniform of a Highway Patrolman as (what else?) the helicopter pilot. Most of the camerawork from the helicopters for these programs was done using a handheld 35mm camera. Once again, however, the aircraft was part of the story.

Tyler Camera Mounts. From Tyler promotional material

Tyler and his equipment are responsible for some of the most impressive uses of aerial photography that continue to stand the test of time today. One example is from the film “Funny Girl” starring Barbara Streisand filmed in 1967. Jerry Grayson, pilot, director, cinematographer and owner of Helifilms, an international aerial filmmaking company based in Australia, describes the shot, reported as part of McClain’s magazine article.

“There’s a very long continuous move that starts wide on New York, that finds a tugboat on the river, that goes down to the tugboat, that finds Barbara Streisand on the bridge of the boat, that goes in tight on her head and shoulders, that hits the end of the lens as she hits the high note in the middle of the song, and then goes out and up and back. It doesn’t matter how much expensive gear you’ve got, you need to have not a little luck, a great deal of skill, and a telepathic relationship between pilot and cameraman to pull that off. And Nelson Tyler pulled all that off right back in the mid-sixties.”

Click through to the next page for the Wescam gyro mounts and the origins of live television from the air with the KTLA Telecopter!

“National Helicopter had an exclusive agreement with Tyler for the first five years of the mount’s existence for it to be used in our aircraft,” Hart says. Tyler’s mount “still sets a standard that cannot be beat in many ways.” But Hart also gives credit to the artistry of the operators who were responsible for the classic shots and the symbiotic relationship they must have with their pilots. He says “…we no longer have the cameramen… who have grown up with hands on experience with action camera scenarios… I find many of today’s aerials technically excellent and superior in some qualities but lacking in excitement as I feel I’m sitting on a couch in the sky watching the action.”

Stabilized nose mounted cameras with remote controls inside the cockpit came along with the introduction of the first successful gyro stabilized camera system, Wescam. The system was created under military contract by Westinghouse of Canada. Hart explains, “This is the ubiquitous ‘ball’ seen on the side of the helicopter in its early configuration.” Sometimes it is also seen underneath the helicopter. National Helicopter operated the first and only Wescam for many years until another was built.

The early Wescam mount on the right of the helicopter. Notice the counterbalance on the left side. Courtesy National Helicopter Service and Engineering Company

Hart remembers the most interesting trip for him was trailoring a Bell Jet Ranger helicopter and the Wescam to the Evel Knievel Snake River Canyon jump in September, 1974, for Editel. The production company was handling the closed circuit theatrical telecast of the event when ABC decided not to broadcast it. “I spent a week in a compound surrounded by over 10,000 Hell’s Angels camped around the launch site waiting for the event. I was standing about 10 feet from the launch platform when it was fired. It was a bust.”

At work on the KTLA Telecopter. Richard Hart, Sr, in the checked shirt, John Silva to his right. Kneeling are KTLA engineers Harold Morby, left, and Roy White. Courtesy National Helicopter Service and Engineering Company

“All we had to do was condense 2000 pounds of equipment down to 400 pounds and figure out how best to transmit a picture [while airborne] in a practical and economic manner,” Silva said in a later press release.

The vibration Nelson Tyler would set out to solve on his motion picture camera mounts in the early sixties would also prove a major nemesis for Silva and his crew. Overheating proved to be troublesome as well. Because the Bell 47 cockpit barely had enough room for the pilot and one passenger, all the electronics had to be placed outside affixed above the skids and in direct contact with the downwash of the main rotors. One person who never receives credit in the accounts of the Telecopter’s development is Tom Palmer.

Modifications affecting the airworthiness of a helicopter must be overseen by a certified FAA mechanic with Inspection Authorization or a certified FAA Repair Station. Palmer and National Helicopter were both, respectively. Palmer had to sign off on all the work, taking full responsibility of the safety of the aircraft. The Telecopter literally would have never gotten off the ground if it weren’t for Palmer analyzing the entire project from disruption of airflow to electrical loads to what affect the microwave equipment would have on flight capabilities.

Even so, the vacuum tube driven equipment failed in an initial test due to overheating and vibration. But the crew worked to isolate the more sensitive equipment and alleviated some of the heat build up (sometimes packing dry ice into the electronics compartment in later flights). Finally, on July 4th, 1958, they made their first successful transmission from the air and the Telecopter was born.

The first flight of a live television unit in the sky – KTLA Telecopter. Courtesy National Helicopter Service and Engineering Company

During the Telecopter’s first four months of operation, KTLA reported selling a record $500,000 of advertising. Procter & Gamble spent another $250,000 specifically to sponsor Telecopter coverage. But stations around the country still needed to be convinced the cost was worth it according to Hart.

Within five years, the Telecopter proved its value with live coverage of two major disasters in the Los Angeles area – the Bel Air Fire (1961) and the Baldwin Hills Dam Break (1963). Hart says stations took notice of the viewer reaction to the dramatic live pictures of the events. Once they observed that anytime a big story broke in Los Angeles, the public would instantly tune to KTLA, stations began planning for helicopters in their news department budgets.

With viewership in decline and belt tightening at television outlets around the world, the helicopter has, for many stations, become unaffordable. Hart cites the numbers, “There are only about one third the news helicopters flying today as there were six years ago.”

Regarding drone mania, Hart tells me that in order to stay up with the times, National Helicopter has partnered with some drone experts so as to supply them to the movie industry as part of the company’s cinematography packages. He says it’s interesting to note “those proposing using drones on the set are quoting and planning to charge substantially more per day than we do for an entire helicopter/camera/operator/pilot package.”

But, as he adds, “That’s another story in itself.”