Single-sensor cameras fall into two camps: those that are sensitive to far red, and those that are sensitive to infrared. The Canon C300 is sensitive to far red, which means that IRND filters will work–and hot mirrors won’t. Come see the difference…

RED cameras are the only cameras that are truly sensitive to a form of infrared light–near infrared–which falls at around 800nm on the electromagnetic spectrum. All other single sensor cameras are sensitive to far red, which comprises wavelengths around 700nm. (The visible spectrum runs from violet, at 400nm, to dark red, at 700nm.) Far red is on the very edge of the visible spectrum, and while our eyes respond to it somewhat they don’t respond in the same way that a camera does.

Long the bastard stepchild of the NTSC color world, modern cameras reproduce red more faithfully and vibrantly than any SD camera ever could. This ability comes at a cost, though: cameras can’t really see the world the way we do, so we must expect some variability.

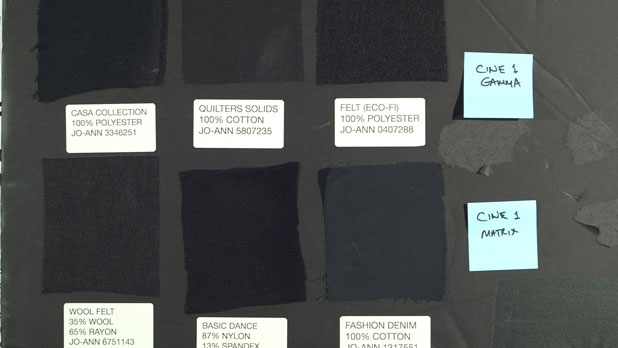

This is my fabric IRND chart, made with common materials found at the U.S. chain store JoAnn’s Fabrics. Some of the fabrics reflect far red/near IR and some don’t. I’ve been using this chart for years now. (As you can see it’s getting a little beaten up. Infrared will do that.)

Near IR and far red contamination typically show up when using standard neutral density filters, because NDs block visible light but allow far red/near IR to pass. The heavier the ND, the less visible light is passed, and opening up the stop to compensate for this lets in a lot more far red/near IR. Typically far red/near IR isn’t visible when shooting without ND filters, but we’ll see an example in a moment where that’s not the case.

I chose Cine1 matrix as it’s representative of the color response of the C300’s “Cine” matrices. The camera “matrix” is the bit of software that bends the sensor’s raw color into a form that we find pleasing. There are nearly infinite ways that this can be done, and this bit of math is a large part of every camera manufacturer’s “secret sauce.”

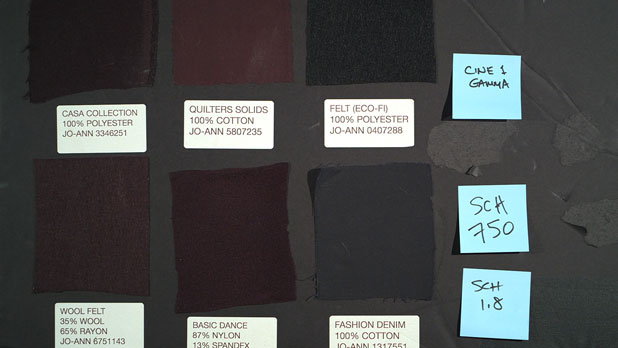

This is the EOS color matrix. It is, by far, the most saturated matrix in the camera, and therefore the least likely to be used. (Strong, saturated colors tend to appeal mostly to children and those who are not terribly sophisticated visually. I don’t know a single cinematographer who would find this matrix appealing except as a special effect.) What’s interesting is that we can see some far red contamination in the middle patch on the top row and the two leftmost patches on the bottom row in spite of the fact that I’ve not changed anything optically. It appears that far red contamination is present even without adding any ND filtration–but it’s only visible if you opt to use the most saturated color matrix in the camera.

If you can’t see it, it doesn’t matter.

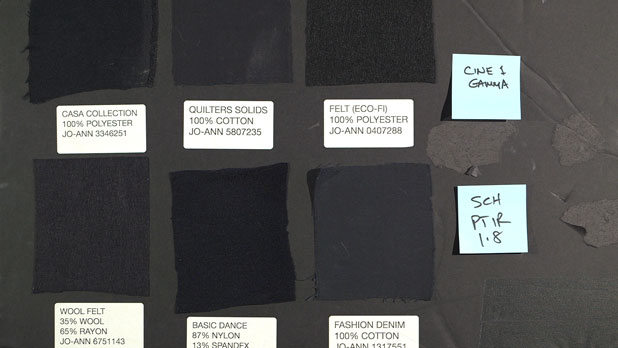

I’ve added a Schneider ND 1.8 filter to the mix. Far red contamination is dramatically obvious here. I’ve switched back to Cine1 gamma, which is why the color is a bit on the subtle side. I used a Schneider ND simply because that’s what most rental houses seem to carry. (I shot these tests at Chater Camera.)

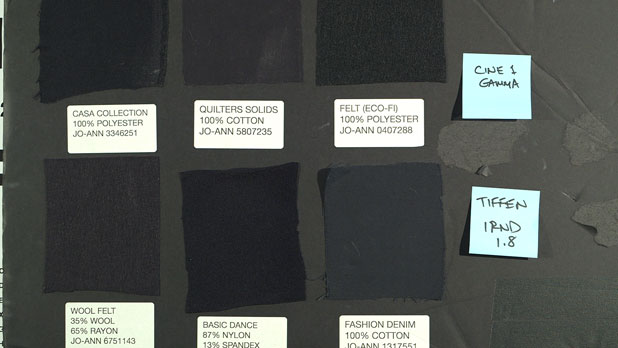

I’ve replaced the regular ND with a Tiffen IRND 1.8. The IRND line has a green dye that absorbs far red between 680nm and 700nm, eliminating far red contamination. This is different from a hot mirror, like the Tiffen Hot Mirror or Schneider Tru-Cut IR 750, which cuts much higher in the spectrum. The C300’s sensor has a perfectly functional hot mirror in front of it, so adding another hot mirror will have no effect because the on-sensor hot mirror is already removing near infrared wavelengths from the optical path. Doubling up on hot mirrors does nothing more than what a single hot mirror can do.

While the IRND removes obnoxious far red contamination from fabrics it can also cause flesh tones and red fabrics to lose a bit of lustre. This is not a filter issue, but simply a fact of life: the sensitivity of modern sensors to far red creates a much richer red palette than we’ve had before, so removing some of that to compensate for unwanted far red contamination will most likely affect other things in the frame.

The Schneider Platinum IR (PtIR) ND 1.8 filter does much the same job as the Tiffen IRND 1.8 did. I chose ND 1.8 for this test as ND filters pass less than 1% of visible light at that strength and manufacturing defects, in the form of color shifts, tend to show up fairly quickly. I don’t see any issues in either the IRND or PtIR filters. When in doubt, though, ND 1.5 seems to be the point just before far red filters fail if you get a bad set or use a new product from a different manufacturer.

This is how we know we’re dealing with far red and not near infrared. The Schneider Tru-Cut 750 works marvelously on RED cameras, whose hot mirrors cut higher on the spectrum (above 750nm) than most other cameras (above 700nm). The fact that this filter does nothing to reduce color contamination shows me that the issue here is visible far red and not invisible infrared–and this does seem to be the case for every single sensor camera other than RED cameras.

As I’ve stressed before, what we’re seeing here is not a camera defect but rather a side effect of how silicon sensors see the world differently compared to how we see the world. Eliminating wavelengths above 680nm at the sensor restricts the variety of reds that a camera and reproduce and may have a negative impact on flesh tone, but sometimes that compromise seems reasonable if something else in the frame shows a strong and distracting color shift. It’s much better to make that filtering decision on a scene-by-scene basis rather than cripple the camera outright by filtering far red on the sensor.

Art Adams is a DP who sees strange things in the dark. His website is at www.artadamsdp.com.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now