The ProVideo Coalition Podcast features interviews and insights from experts across the industry and has allowed us to highlight industry news and also explore some critical industry topics. Our new “Conversations with Adobe” installments of the podcast highlight the products and people from Adobe that are making a major impact on our industry.

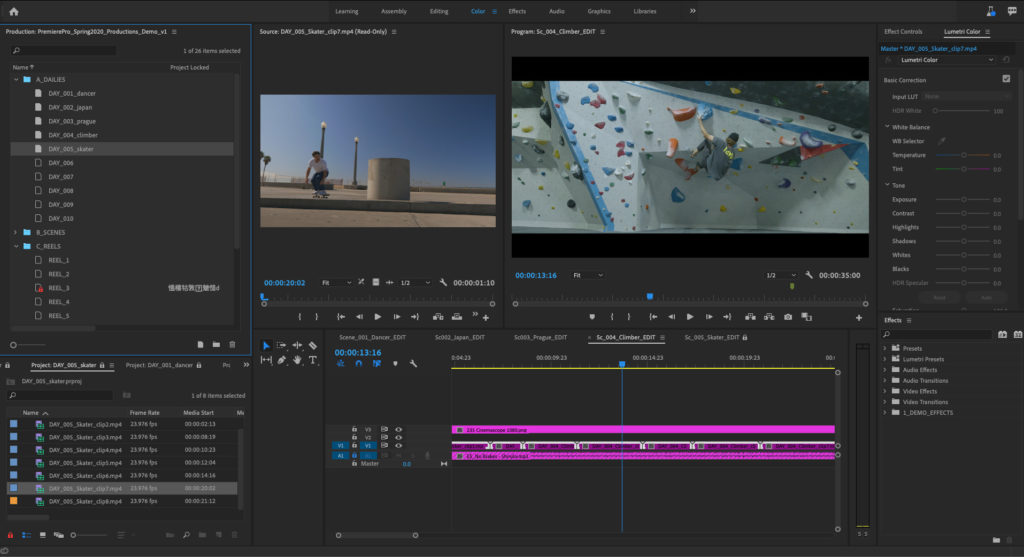

First up is a discussion with Matt Christensen, who’s an Adobe expert and was one of the main people on the team that developed the recent Productions workflow, which rolled out around the time we should have been in Las Vegas for NAB. When the Productions workflows were announced, I wrote about how the architecture allowed users to think of a Premiere project as a bin. Think about no longer having duplicate clips as you move a sequence from one project to another and you see an immediate benefit.

I talked with Matt about Premiere’s history in Hollywood, how Productions can be used in the real world and much more. You can listen to this conversation both on Anchor.fm or Apple Podcasts or your favorite podcast catcher.

The following conversation has been edited for clarity and flow.

Scott Simmons: Let’s talk about the Productions workflow, which is something we have previously discussed with Van Bedient from Adobe. Even though we didn’t physically go to NAB this year, is it still considered an NAB-release?

Matt Christensen: We absolutely were shooting to release this for NAB and NAB became a fuzzy target in terms of where this work started and stopped. April was the release of Productions, which is right around NAB time, but April was also my three year anniversary at Adobe. So it was also a nice clean anniversary for me.

Scott Simmons: I knew you hadn’t been there for a long, long time, but you came on board around the time they were opening up an LA office for Adobe’s Post Production World, didn’t you?

Matt Christensen: Yes, that’s right.

There had always been a few employees in the LA area, and Van was one of those, but there wasn’t really a dedicated engineering effort in the city. So whenever we engaged with or worked with any customers in the LA area, it involved flights and hotels and interrupting some of the engineer’s schedules to make that happen. So it was decided, and I think it was a great idea, to put some people on the ground in LA and have a formal office to work from. That led to hiring some people and that’s where I came in.

I should clarify though, that at the time I was hired, that office was in Santa Monica. We had been in the process of moving to Culver City before the pandemic caused everything to shut down. That’s where there’s a new, larger, Adobe office due to some other acquisitions that were made outside of the Creative Cloud part of the business. So it’s going to be a much larger office. We have our desks there and there’s a really high-end edit suite that we use to test on the highest end gear but also for training and other kinds of events.

Scott Simmons: Can you say if that presence in LA is a direct result of Adobe saying, “we want more feature films, we want more broadcast television, we want more series work, etc”? Or is it more of a natural progression of where Premiere is and where Adobe, in general, is going? I think of this specifically in terms of Premiere, but I’m sure it’s not just Premiere because Adobe wants to make inroads into feature films and in “Hollywood” with their various other tools.

Matt Christensen: It was kind of two forces at the same time.

As you said, we wanted to have that presence in Hollywood so that we could have people on the ground that can be part of the post-production community here in LA. It’s also a reaction to the fact that Premiere already was making those inroads and this is a market that we want to make sure is supported as it grows. So it kind of comes from both sides.

Scott Simmons: Premiere is not brand new in the world of episodic TV and feature films. It’s been used over the years quite a lot, and tell me if I’m wrong about this, but I remember one of the first feature-length films edited many years ago on Premiere was called “Dust to Glory” and it was about racing some kind of off-road race. Does that ring a bell?

Matt Christensen: That’s from well before my time, but I have heard that title discussed on our team.

Scott Simmons: I had to quickly google that, and I see that “Dust to Glory” was a very early Premiere film, but it wasn’t edited on Premiere, although from what I gather, it was shot on film, and Premiere was used to conform it do the final online. DigitalFilm Tree put out a white paper on that back in 2005 which is a really interesting read, and it’s still available to download.

All of which is a long way of saying that Premiere is not brand new to this. Features have been produced on it and we’ve had many television shows cut on it. It seems to me that this sort of push into this new office in LA is about having a presence in the space, but how does the engineering side work around that? Because if you decide you want to take Premiere to the next level, is that more of a marketing effort or an engineering effort?

Matt Christensen: A lot of the marketing was happening even before there was an LA office, and the LA office is more specifically about the engineering side. That manifests in multiple ways, from us being able to easily make appearances at industry events in LA, but also going to visit cutting rooms and getting feedback or helping people with any issues they might have. It’s kind of a combination of all that, but it’s also a manifestation of the fact that within Premiere there exists our team, which is explicitly tasked with these kinds of features and engaging with customers in this manner.

Scott Simmons: I have an interesting question for you about being able to step into big post-production workflows in Hollywood: What was Premiere lacking before you came along? While I think the new Productions workflow has made it a more appropriate choice, did your engineering team ever recognize that you would have to do some work under the hood to make it a viable option for this market?

Matt Christensen: The thing to keep in mind is that you’re talking about where Premiere was being used, but it’s also been used extensively for many years in other markets like broadcast, which includes a lot of stuff here in LA. That’s things like trailers, commercials, music, videos, etc. With those kinds of projects, they were more or less getting by and things were working well with a single project format.

As we engaged with and worked with more filmmakers and larger TV shows that were trying to use Premiere or wanted to use Premiere the thing that we kept coming up against was a limitation of how far we could take the concept of a single project. That has kind of two main friction points, which is related to the size of the project as a single project file and how multiple people can interact with that file. As it scales, it becomes harder to work with. Also, because it’s a single project file, it can’t have more than one user working in it at a time. So those are the kinds of problems that TV editorial teams and film editorial teams would hit.

Scott Simmons: You mentioned project size, and as a longtime Premiere user, it’s something I’ve faced. I remember days working in Premiere where I would bring in a moderately sized project and a few days into it, your project size would balloon into being very, very large.

If you think about a Premiere project file, it’s almost like a pointer file. It’s a small file that tells Premiere how to playback to media and it always points back to the media. There is no media itself embedded in a Premiere project file. Your audio clips, your video clips and whatever else lives on your media drives and the Premiere project points back to them to simplify things. But we would see those project files themselves begin to get really, really big, way bigger than you would ever think. Over the years though, Adobe began to slim those back, and I guess there’s optimization going on where the projects stopped getting as big as they did in years past. What was it that took us from these huge, bloated project files into the single smaller project file? Was that a conscious entity nearing effort as well?

Matt Christensen: I can’t say for certain because it kind of depends on when you would have experienced that happening. I can tell you that while you’re correct that the project format is a description of everything in the project. So in theory, it doesn’t contain things like media.

At one point it was in an uncompressed form and then at some point, it did switch over to a compressed file format. So imagine having a Word document with 10,000 lines of text in it and then you zip up the Word file. It’s going to get a lot smaller, but then you can just unzip it really quickly and you’re back to where you started. So Premiere uses that kind of compression in its project file format. At some point in the past Premiere didn’t do that, and that might have been when you recognized the night and day difference.

Scott Simmons: I don’t remember what version it was, but I do recall that in one of the new releases it was pointed out that the project files were smaller and more reliable.

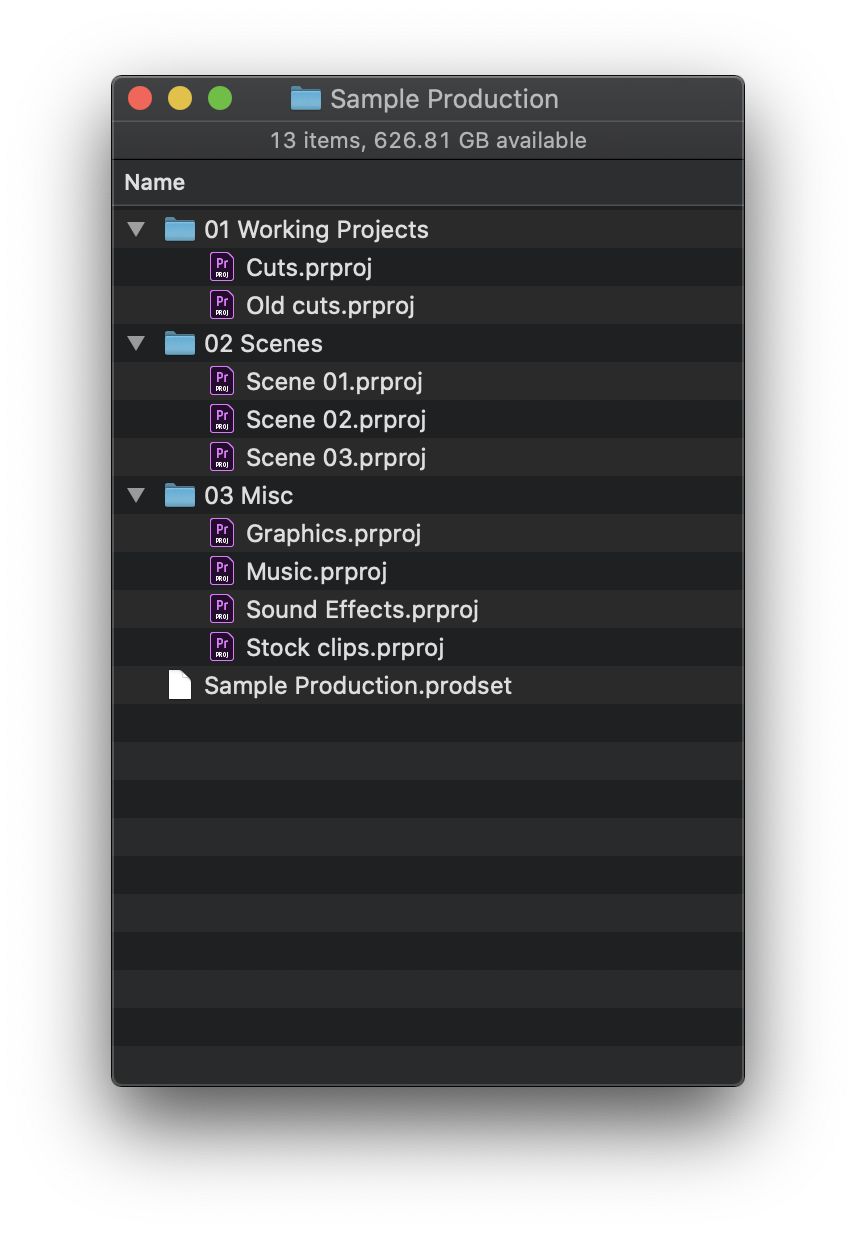

So what your team did is sort of the next evolution of that project file with Productions, but Productions itself isn’t a project file. We don’t want to get too deep into the mechanics of Productions, but can you explain what a Production is versus a project because in Premiere, you can say “File>>New Project” or say “File>>New Production”. Can you give us an overview of the difference between the two?

Matt Christensen: I think the key to understanding the difference is to talk about the middle step which was being built right as I started at Adobe a few years ago. That was called shared projects and that was sort of an, on the way to Productions step that we had to take to start to break apart projects so that you were only working in the part that you were working in and someone else could be working in the part they were working in. That allowed for our first stab at collaboration.

The conceit of shared projects is that each of the projects had no concept that the other existed and Premiere sort of behaved as if each one was still a separate project. It was the thing that worked and it helped a lot of people when compared to the alternative of not having it, but we knew that it wasn’t a final solution. That’s why our team kept working at and getting to the point where we got to Productions.

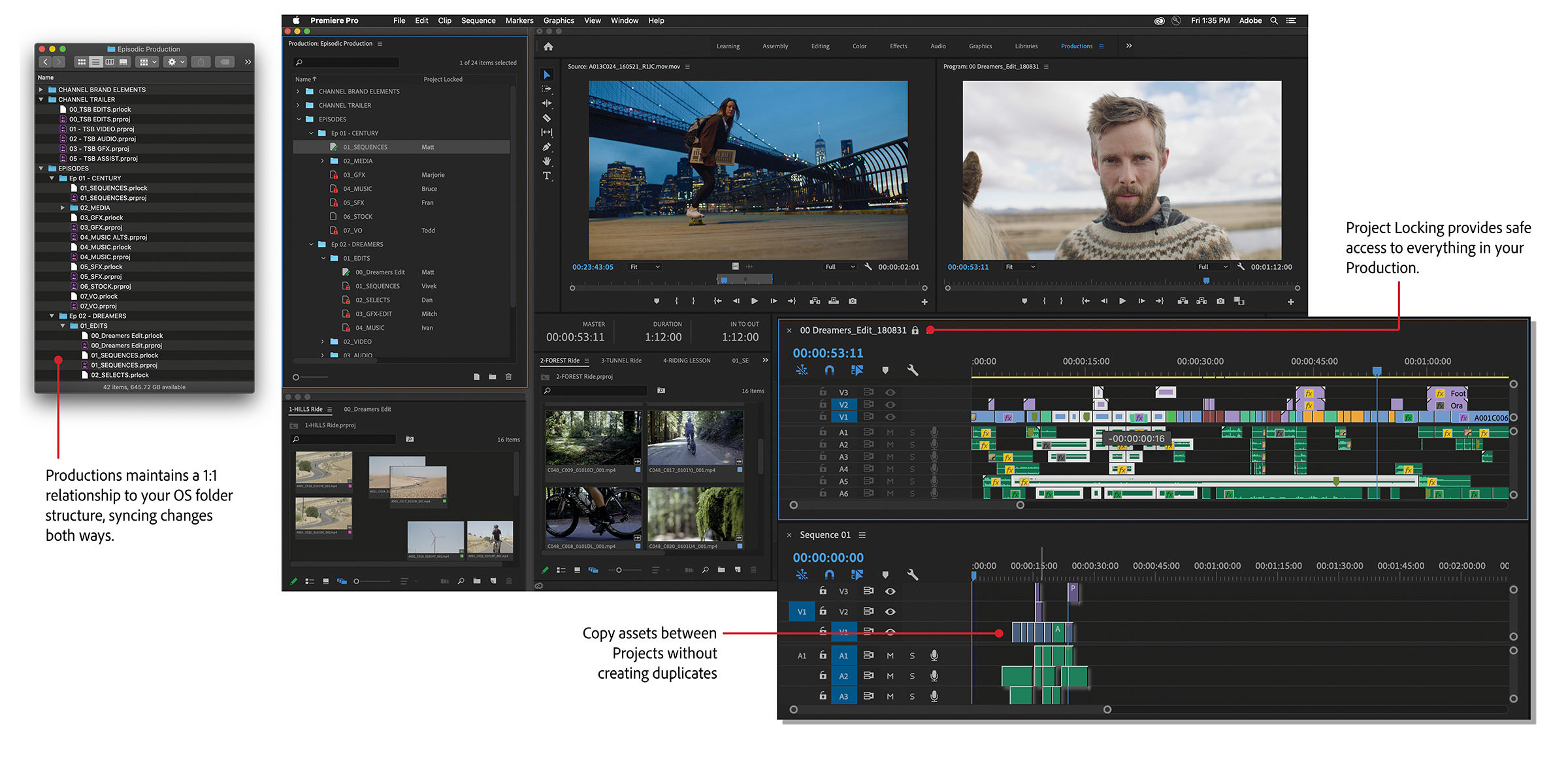

That takes us to what is different about a Production and the difference is that because it’s contained within a folder that Premiere can identify as a Production, it’s able to treat those projects differently than it would treat just two unassociated projects that you happen to have open at the same time. For example, it can reference clips across the project and say, “this clip is in a timeline in this project, but I know that it came from the other project and therefore it doesn’t have to create a duplicate when it lands in the timeline”. Without limiting the scope it’s not really feasible to do that.

Scott Simmons: So let’s talk about not having to duplicate the clips from project to project, because that’s a big one. In the past, if you brought another timeline into Premiere that is referencing media already in your project that came in via a new XML or a new project import, oftentimes, it would have to duplicate that media and you’d be stuck with the same master clip twice in the project. When you talk about big workflows with feature films, or episodic TV, why do you think it’s important that they do not duplicate clips across projects? Why not have four of the same master clip in the same project? Is that a pain in the butt?

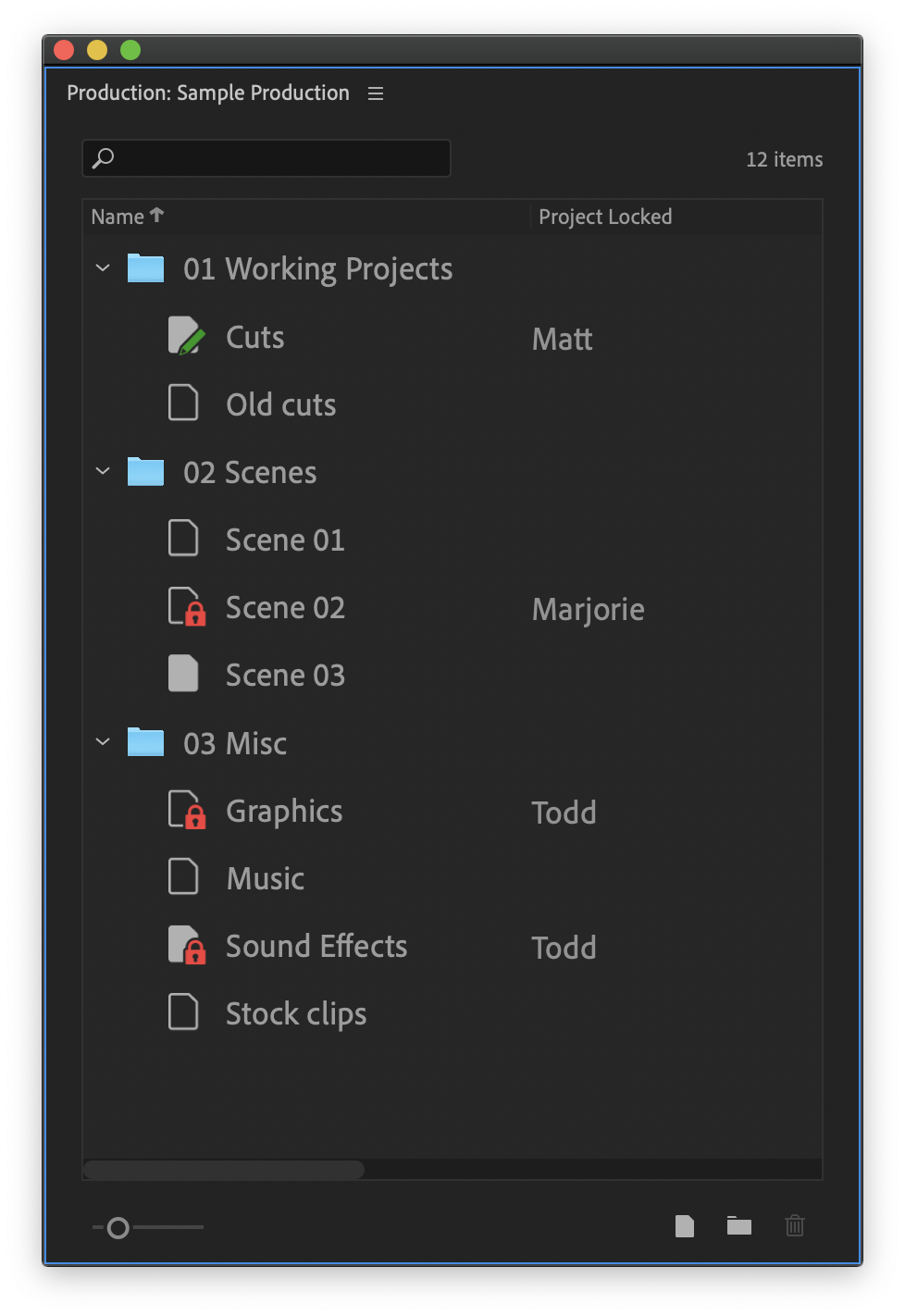

Matt Christensen: It is a pain in the butt for obvious things such as having to go in and add a piece of metadata to one of them. Which one is the one you should add it to? Do you have to keep finding it in the timeline and using Reveal in Project to figure out which one is associated to which? We had done a lot of work, both our team and the Premiere team in general, to improve what you’d call in software development, the deduplication. We wanted to make it so Premiere could get better at figuring out that these clips are actually the same and not making duplicates if it didn’t need to. And we did a lot of work on that.

Today, Premiere is the best it’s ever been at figuring out that if some of the clips are already in your project, and you add a sequence to it, it can do that and figure things out better. But it still doesn’t help you if the clips don’t exist in the project, right? You have to bring in those clips with it. And so in Productions that fundamental rule is no more. Premiere is able to understand that those clips live in a different project and don’t need to be created in the destination project.

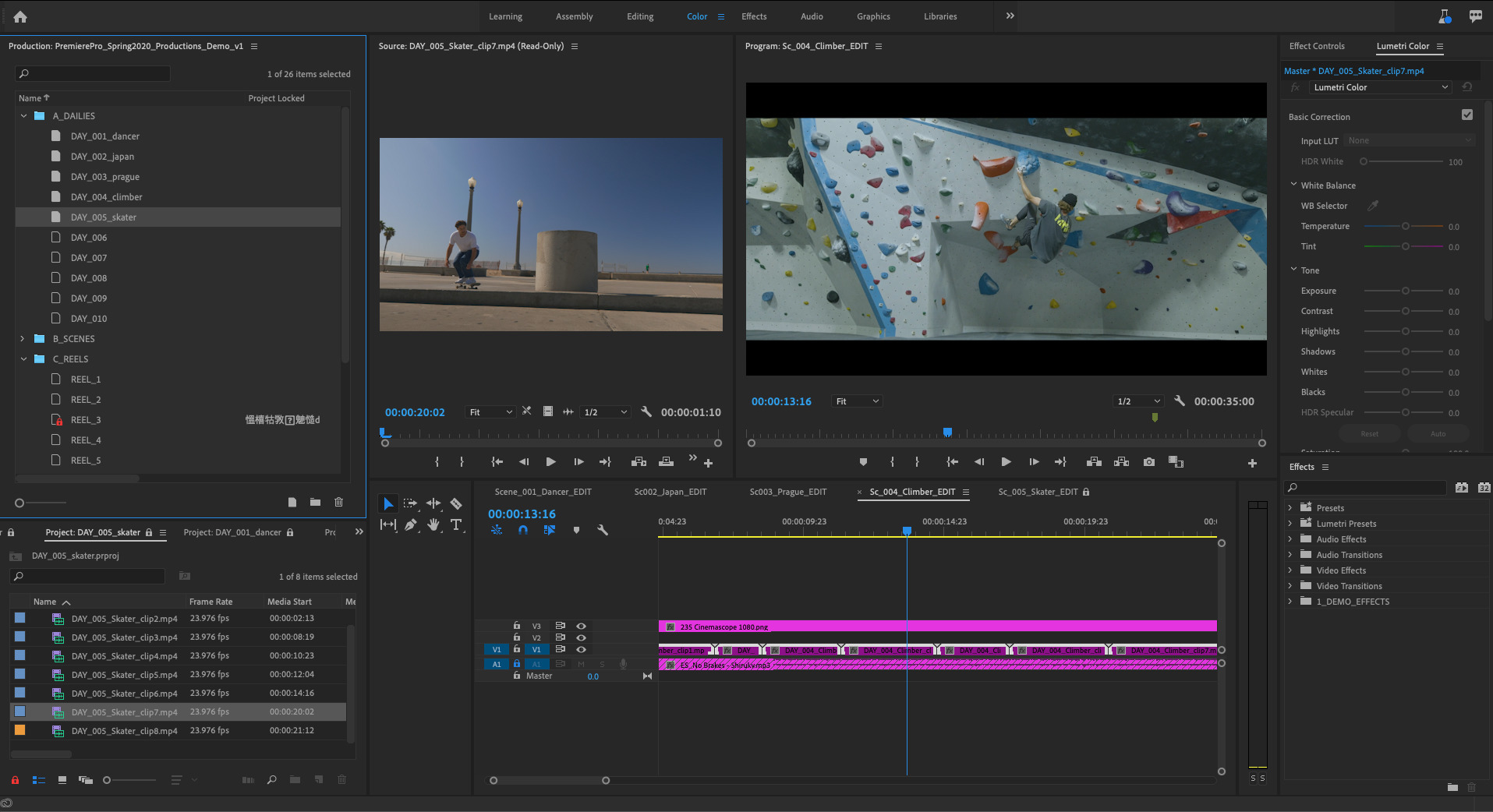

Scott Simmons: Take us through the setup and what the basic workflow would be for a post facility. Say I’ve got twenty editorial stations and five or six assists stations. I’ve got all those machines networked together with my shared storage. We get in several weeks of media from a shoot and it’s all sitting on the server. I’ve got three assistants and I’ve got four or five editors sitting there ready to go to work. What would be the baseline workflow for me? How would you set it up from the beginning in that environment?

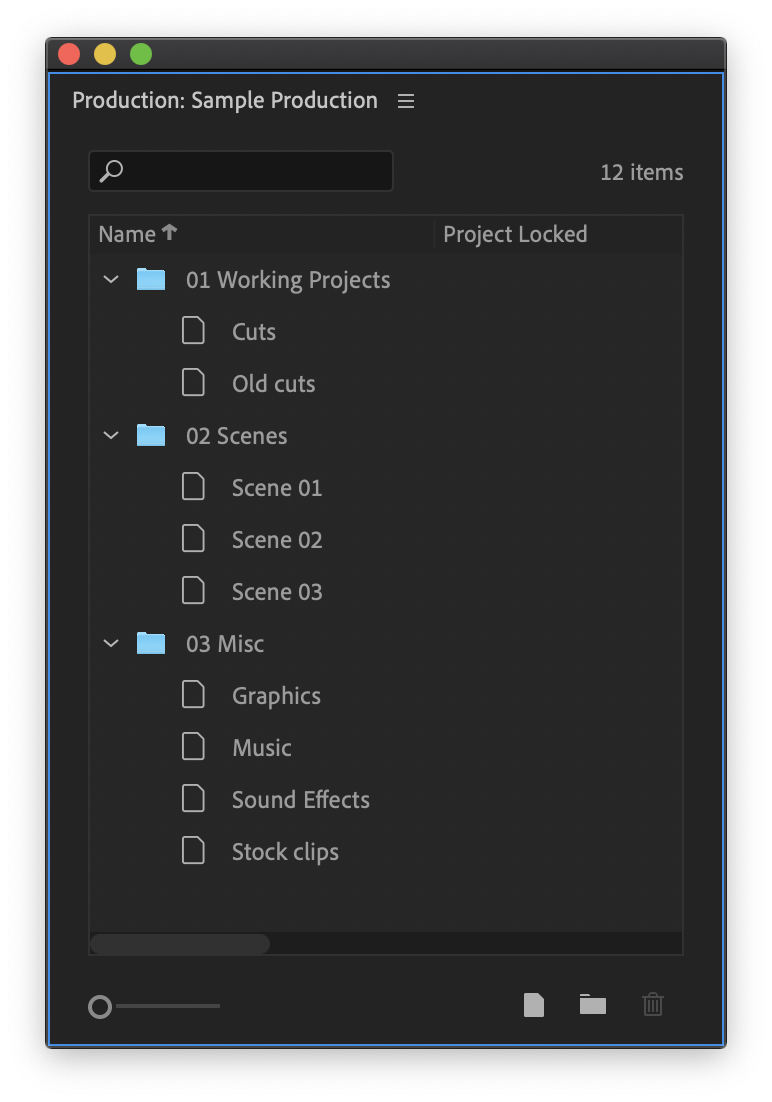

Matt Christensen: You would usually have one person create the Production but once that initial Production has been created, you could have multiple assistant start to break apart your footage. If you only have the one you would just have them work on it, much like a traditional project, except they would break apart the footage into components in the smallest way possible that was still appropriate for the job.

If it was a traditional scripted show, you might have a project for each scene of the script so that later on it’s very clear what belongs to what and someone working in scene five can take the lock to that project and not affect someone who needs to work on scene six, etc. And you just start to build that out.

Once the Production is built out, editors come in and they might have a working project or they might be working in an Act One project or whatever is appropriate for that show. It can just sort of organically scale up until a lot of the shows you’ve been working with have 100 to 500 plus projects in their Production. They just sort of blink and it happens like that. They’ve just been working away and it scales very efficiently.

Scott Simmons: It really does, because it can creep up on you if you’ve been working weeks and weeks on a project, especially on episodic stuff where you’ve got multiple editors. That means you also have episodes that have to keep some very specific timelines.

You mentioned locking and we talked about not getting the mechanics but I think maybe we do need to get into mechanics a little bit because the idea of locking, and I have to jump back to the legendary Avid Bin Locking, which was one of the early collaboration features of all nonlinear editing applications. We have a locking mechanism in Premiere now with Productions and I think it’s worth mentioning that in Productions, your project file can be treated like a bin used to be. You can open up the Production and you have different projects, but you can open up projects and still have bins in there. But if you’re treating the project itself like a bin, how did the team decide, “all right, let’s make the project almost like bin” ? To me, it seemed like an odd choice until I used it. Then I saw how it works and thought it made perfect sense.

Matt Christensen: Just like any kind of project, when you’re working in software development there are a lot of pressures to not reinvent the wheel. You have to sort of work within the constraints of where you already are and so we looked at whether or not we wanted to create a new type of project file format or a new .pr something that would be this new kind of production bin or production component. And we could have gone that way. But then we’d be drawing a line in the sand and sort of complexifying the offering.

Scott Simmons: I like that word. Is that a real word?

Matt Christensen: My brain just told me it’s not a real word!

Anyway, all of what would be us making things more complex. Then you’d have to be concerned about having something in an old .pr project that you needed to get it into a new or current project. So the more we workshopped the idea, just even conceptually, it became apparent we could just use existing projects and build the Production scaffolding around them, rather than start from a completely new state.

Scott Simmons: As I use Productions, and I used it recently for the first time extensively on a job. It was with two editors and an assistant working on a large corporate production where we all had to access each other’s stuff as a change came in, or as a piece of the corporate production came in. You never knew who was going to be able to jump onto it first so someone else had to jump onto it. The simplicity of the Production panel, which is a new panel in Premiere, and seeing this list of the projects within the Production, and seeing some color-coded icons that would tell me I had one open and someone else also has open so I had read-access to one but write-access to another. It was simplified in a way that made good sense and made us be able to really easily pick up on it and jump into it. You talked about moving into more of a Hollywood style workflow, so was all of that part of the design? Did you see that it needed to be easy to use and easy to understand?

Matt Christensen: That was absolutely a guiding principle as we were designing this. It also drew on my background working in post-production, as I’ve been an assistant on every NLE that’s out there. We have a few others on our team who come from post as well, so we knew that it was very important that it needed to be easy to understand.

One of the other benefits we get from using the existing project file format, instead of remaking it, is that you can just take an existing Premiere project file and drop it into Production. Or you can take one out and it can still open on its own in Premiere without needing the Production that created it. It’s insanely flexible and we were really excited about that being the way we were able to build it.

When it comes to talking to, say, Avid users or people who have used that sort of workflow before, we learned from shared projects that we wanted to make it as seamless as possible. It was kind of difficult when we were evangelizing shared projects to do a translation because it was similar to Avid stuff but a little bit different. So it was definitely key to us in Productions that as we were getting it beta tested and having some of the first customers use it that we were very careful to make sure that the questions they asked were ones we could either address or make clear so that future users wouldn’t even have to ask those questions.

Scott Simmons: Let’s talk a little bit about how you were able to bring Productions into the world. Beta testing it in a mission-critical feature film seems scary, but I’m sure you had to do just that. How do you take such a monumental change in how Premiere operates and test that in real-world environments without scaring people and making sure you’re actually getting people pounding on it in a real-world environment?

Matt Christensen: The nice thing is that the demand or the sort of pent up desire for this feature was already there. People want to use Premiere for a lot of reasons. But one of the main roadblocks to them using Premiere in these environments or these workflows was basically everything that we didn’t have yet in Productions. Just mentioning to some of these shows that this was something we’re working on got a positive response. We didn’t have to sell it to them when we asked whether they wanted to test it. They asked us if they could try it out and told us that they would use it on their show.

Part of it is that with people like Van and other people that work in the field office in LA, they have great relationships and they were able to provide the confidence in users so they knew that if they did encounter problems, Adobe would support them. We’d take all of their calls and could send someone out as needed. Once they knew they weren’t going to be left in the dark people were really comfortable and happy to try it out, give feedback and really help shape it.

Scott Simmons: Being that you can, at any given point, take a project and sort of extract it from the production if it needs to be standalone seems like it could help make people test it out in real-world workflows. So that feels like a potential off-ramp as you’re trying to get someone to use something new because sometimes it’s hard to get people to change. You can outline, “here’s why this update is going to be better,” but look at how many ancient versions of Media Composer are being used in Hollywood. They’ve got established workflows and I know sometimes it’s a financial issue to move away from something like that, but I think sometimes they’re just scared. They’re scared that something new is going to break. Saying “try something new” can sometimes be a big ask.

Matt Christensen: Yeah, absolutely. And that’s another reason we went with keeping the existing project format as opposed to making something totally new. It simplifies that whole scenario. Projects and versions can more easily talk to one another with and without Productions. So that was big.

Scott Simmons: So what comes next for Productions? I know you can’t talk about all the future feature coolness, but on the surface, you can look at Productions and see how simple it is and that it just works. So how much else is there to do?

Matt Christensen: We have plenty of great ideas of what we’d like to do next with Productions.

I don’t have a computer science degree or a software development background, but one of the key things I’ve come to understand about this kind of work is how difficult it is to get that 1.0 of a feature out because we had to start ruthlessly cutting. Does this little thing need to be sorted out, or can we ship it without that totally figured out? If you never stop and you never put the pencils down then it never ships, right? So we do have a significant list of things to sort out that we had already identified ourselves. Even before it came out, we knew we would have done X-Y-Z if we had another six months to work on them.

A key thing we built into our schedule between April and about now was to not immediately jump on the next thing. Instead, we’ve been explicitly listening to customer feedback now that it’s out and being used. So you’ll see me and some of the people on the team on social media and on some Facebook groups and actively engaging with people who are wanting to use productions or have questions. We want to see where the rubber meets the road and where the real issues are. So that’s informing us as we build our list of what’s going to come next.

Scott Simmons: You mentioned you don’t have a computer science degree or engineering background and that your background is in post-production.

Matt Christensen: I have a film production degree and I focused in post-production.

Scott Simmons: So can you talk a little bit about this intersection between someone like yourself who’s an expert in workflows and the post-production world and then the engineers who have to implement ideas? From my understanding of software development, sometimes the engineers and the people that are designing how these tools will be used in the real world are at odds with each other as far as what’s needed and what’s possible. How does that work?

Matt Christensen: Honestly Scott, that’s been one of the most fun parts of my job. They’re those meetings that can sometimes be hours long, where we just have to end it because it’s 6:30 and we’ve already been talking for three hours. And that’s where we get into those exact sorts of things.

A lot of the times myself or colleagues on my team who have backgrounds in posts can categorically say a certain thing is what an editor expects. We might want it a certain way, but there are extremely valid engineering reasons why it’s going to be better to go a different way than what we’re fighting for and we have to find a compromise. There’s also designers and user experience input that we get for a lot of these things. Their input is just as valid so the conversations can get tense. I wouldn’t say they’re combative, but we’re very passionate people and we all enjoy our backgrounds and we want Premiere Pro to be the best so it’s a very interesting melting pot as to how it all shakes out. Getting to have those kinds of discussions and hash everything out is something I really enjoyed.

Scott Simmons: But the editor is always right, no?

Can you talk about archiving when you’re done with a job? It used to be you archive your media, your archive your Premiere Pro project. Productions gives us a new thing because when you create a new Production in Premiere, you get this new folder on disk that holds all of the projects. For years, I’ve put my Premiere projects on Dropbox and I worked with them off of there. Recently I’ve been using Postlab, and it’s a great workflow tool. How does all of that integrate with Productions? Is it just a matter of me taking the Productions folder and archiving that? Or do I just archive the projects and not the folder? How should all of that work?

Matt Christensen: I think the simplest method is the right one. Just treat that Production folder as your project file. So you can move it, you can back it up, you can do whatever you like with it. The atomic unit is that exterior folder of the production.

What we’ve seen a lot of productions do that want to make sure they’re backing stuff up regularly is, at the end of the day or at lunch or at whatever interval they’re comfortable with, they just zip up the folder. That serves as a nice neat point in time and you can put a date and time stamp on the name of that zip. Then you have a clean, progressive archive of your own.

The autosave system in Premiere isn’t doing anything special for Productions. It’s still treating each of those projects as separate ones. You’re gonna be okay if you have some kind of crash or if you needed to recover one of the projects, you could. Back to not reinventing the wheel, it would have been really expensive if we had rewritten the autosave system to auto backup the entire production folder at every interval.

Scott Simmons: So it sounds like the Productions folder is not some kind of magical new thing that that Adobe created. It’s just a collection for all the projects in production and the magic sort of happens in the owner underhood mechanics of Premiere itself. And maybe in the Premiere project file.

Matt Christensen: It’s mostly in how Premiere operations like moving between projects work when a Production is open versus when a Production is not open.

Scott Simmons: One thing I wanted to make sure to mention is that Productions really isn’t just for teams. It’s also not just for multiple editors working together. A single editor can use it themselves. I’m actually going to be starting a documentary job in October where I’ll be using Productions because I will be getting an organized shoot where each little part of the shoot will be in its own Premiere Pro project.

So my workflow plan, and you tell me if it’s a good one, is to create a new Production for the documentary. Then, as I start to put together a paper edit, I will import each little project from each little shoot into the Production and then start to build that up into a new project in my Production which will be my main edit project. And that will be me as a single editor using Productions to speed things along and keep project files small. It seems to me like that’s a perfect use for a single editor working in Productions.

Matt Christensen: That sounds like a solid workflow.

And you’re very right about how Productions can be used. We’ve spoken to a lot of documentary editors who are excited about this because those are the types of editors that may not be very concerned about the collaboration side, but for some of the larger docs we’ve seen might have 10,000 clips in video files can take a little while to open up, even on a fast computer. So you get a huge benefit from when you sit down and open up your Production. You’re just opening the timeline you want to work on and Premiere doesn’t have to sit and touch all 10,000 media files that have ever been imported into the project. Only if you go into those bins does it have to go look at those. So it’s a night and day difference for that kind of edit.

Scott Simmons: The speed advantage of opening a project like that is huge. It’s also just a peace of mind. It’ll probably feel a lot more stable in my mind if I don’t have to wait several minutes for it to load all of this media and my main edit project just opens quickly. Even when I have a 90-minute timeline to string out the entire film, that’ll just be faster to work in on its own than a project that has multiple duplications of 90-minute timelines. Lots of cuts, and as you said, thousands of media files in the project that it’s referencing. So I’ll report back to you on how that goes.

Matt Christensen: Absolutely.

Scott Simmons: Anything else you want to make sure we cover? Any misconception that have been floating around about Productions or that you might want to address?

Matt Christensen: Not about Productions specifically, but I just wanted to say that anyone working on professional film, TV or really any project, we’d love to hear from you.

One of the reasons I was happy to come work for Adobe is that I get to do things like this. I’m not just at a cubicle testing things in isolation. We’re a very open company. While we do sometimes have to be secretive about what we’re working on, we’re not secretive about engaging with customers and getting feedback and being out there and a part of that community. That’s why I like working for Adobe, so don’t hesitate to reach out to us.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now