In this article, we’re going to talk about DaVinci Resolve, when it comes to creating DCP’s. What makes Resolve interesting, and different from the other NLE’s, is the fact that you can use it as your editor to, not only edit your project, but you can use it as the intermediary between your NLE and your DCP creation software. Now, keep in mind that Resolve has EasyDCP functionality built into it, but for the purpose of this article, we’re going to assume that, much like in the other lessons, the goal is XYZ color space and creating JPEG2000 sequences to send to your DCP creation application. Let’s get rolling!

We’re going to use the newest version of DaVinci Resolve for this article, because I figured “Why not? It only came out yesterday, so let’s take it for a spin!”, and to be perfectly honest, as of me writing this article, Resolve 14 was released just yesterday, and we can see if the workflow for all the previous versions of Resolve (which has been the same), can be carried forward. We’re going to get things rolling in this article by talking about bringing your footage in from your other NLE’s like Media Composer, Premiere and Final Cut Pro X. Once you’ve launched Resolve 14 (R14) you’ll be brought to the project creation window. Go ahead and create a new project. What I normally do is create one project per DCP.

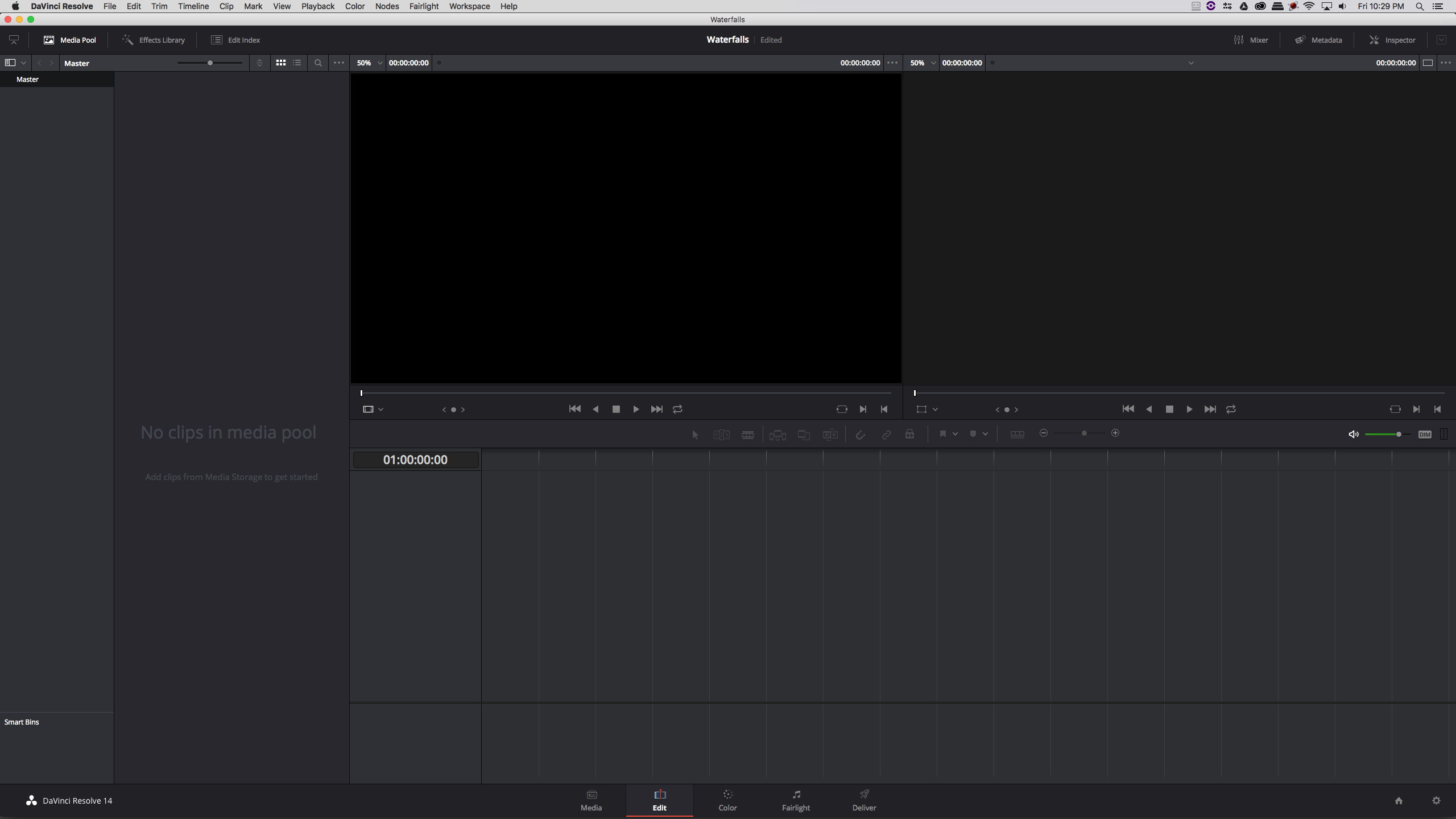

Once you’ve created a new project, I’ve called our’s Waterfalls for the sake of this article, R14 will immediately open, and you’ll be now sitting at the editing screen.

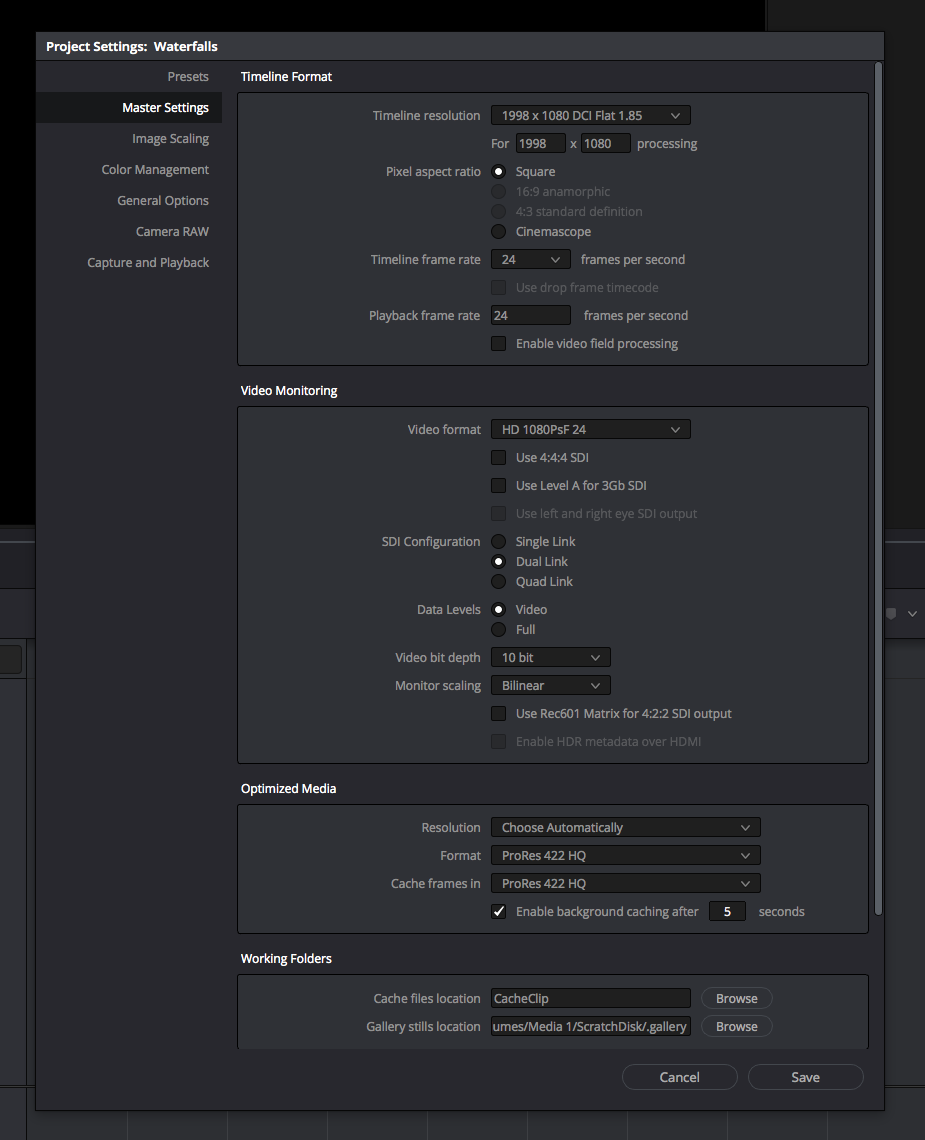

We’ve actually gotten a little ahead of ourselves, and I want to get in first, and set up our project for the DCP creation. The first thing we need to decide, is Flat or Scope. Now, I’m not going to go too much into Flat and Scope formats, as you can read all about them in a previous article about DCP creation. We’re going to assume Flat for this article. Let’s hit SHFT+9 on the keyboard on both Mac and Windows, to call up the Project Properties window. In here is where we’re going to set up our final resolution for creating our DCP. Don’t worry about the raster dimensions of your clip, as we’re going to set that here. We’re going to set our timeline resolution at the top to be 1998×1080 DCI Flat 1.85, and we’re going to leave our frame rate at 24. Keep in mind that your frame rate might change, based on the frame rate you exported your clip as, but you’ll want to keep it as one of the supported FPS’. We’re going to leave ours as 24, as we’re going to do the 23.98 to 24 frame conversion in R14. Once you’ve got your project settings the way you like, simply hit “Save” and we’re ready to bring some footage into R14.

Alright, so let’s back up and bring our footage into R14. Click on the “Media” button at the left side of the toolbar at the bottom of the screen. Once here, you can right click on the Media Pool or Master window, to call up the menu, and navigate to the “Import Media” option. Once there, you can import the clip (or clips) you need to create your JPEG 2000 image sequence from. Once you have it in the Media Pool, you can drag the clip directly into your timeline. You’ll notice that once you do, R14 will immediately tell you that your clip and the timeline’s frame rate/raster dimensions don’t match.

Don’t change anything. We already have everything set up the way we want them in our project settings, so we’re going to conform our clip to our Project’s settings. Once you select “Don’t Match”, your clip will appear in your timeline. You’ll notice that in our case, we’re working with 5.1 audio, which will come into play in just a second. Let’s talk about the video right now. If you look closely at the left and right sides of the record window, you’ll notice that our video is slightly pillarboxed, which we will need to fix. Remember, we’re going from 1920×1080 to 1998×1080, so we’re actually working with a slightly wider frame, and we need to compensate for that. Let’s make that fix right now. If you head over to the Color Tab, we can make the necessary adjustment. Now, don’t get panicked when you see the Color Tab, as we’re only going to deal with a very, very (and I mean very, very) small portion of it, and if you look towards the center of the screen, you’ll notice some buttons that change up the tool(s) that you’re working with. The tool we want looks like this.

This button will bring up the Sizing tools, and you can make a very minor “Zoom” scaling adjustment, to make sure that your footage fits into the frame correctly, and essentially remove the pillarboxing.

With all of that being said, we’ve been talking about working with a single clip that has been brought in from another NLE. If you’ve decided that R14 is going to be your NLE, you have to make an important decision about how the workflow you’re going to use. You can use the technique we’re using here, which is to edit in the raster dimension and frame rate of your broadcast master, export, and re-import a single clip to work with in your R14 timeline, OR you can just set your project up for a DCP delivery (Flat or Scope), adjust all your clips so they fit inside that frame, and then follow the workflow from the second half of this article. Whichever way you choose to work is up to you, but for me, the best way to work is to export a master that you can re-import, and then set up your DCP from there. Again, my own personal opinion.

Now that we have our video sized correctly in the Flat frame, let’s now talk about everyone’s favorite topic, and that is the XYZ color conversion. It’s something that I’ve received a few e-mails about, and it’s from readers who thought that my tip about adding the XYZ LUT into your timeline, and then adding the XYZ>REC709 LUT to see what the conversion process looked like, was a clever idea. This way you can make necessary alterations to the luma and chroma of your footage, and make sure it’s going to look exactly what you expect it to look like. Now, something that’s important to keep in mind is that R14 ships with the REC709 to XYZ LUT built in, but you’ll need to download and install the XYZ to REC709 LUT yourself. To find that LUT, you’re going to head over to Michael Phillips’ 24p.com, and find this link. You’ll notice immediately that you’re brought to the blog entry for exactly what we’re talking about, and can download not only the XYZ>REC709 LUT, but also the REC709>XYZ LUT, if you happened to need it (which we don’t). To install the LUT, so it’s ready to use in Resolve, you’ll navigate to:

Mac:

Library>Application Support>BlackMagic Design>DaVinci Resolve>Support>LUT>DCI

Windows:

C:/ProgramData/BlackMagic Design/DaVinci Resolve/Support/LUT/DCI

Once you’ve copied the XYZ>REC709 LUT into this (these) location(s), either launch R14, or if you’re already in the application, we’re going to need to tell R14 that we’ve updated the LUT’s, and it needs to add this new one to the list, so we can add it to our clip. Head to your Project Settings, and to the “Color Management” section, by clicking on it on the left hand side of the window. Once here, simply hit “Update Lists” at the bottom of the window, and you’re all set.

This is how you add LUT’s to work with them in R14. Once you’ve done this, we’re going to head back to the “Color” module (this is where we did the zoom in on our footage), and we’re now going to add both LUT’s (XYZ and REC709) to our footage. First thing’s first, since i don’t want to alter the main image, in case we want to do some color correction to it, let’s add two new nodes to our image. We can do that by simply hitting ALT (Win) or OPT (Mac) on the keyboard, with the main node selected. Your node layout should now look like this:

Now simply hit the same shortcut to add a second node. You can see where I’m going with this. Select the first node you added, labelled in R14 as Node #2, right click on it, and head down to 3D LUT>DCI>REC709 to DCI XYZ (or P3 or sRGB, whichever color space you’re working in).

This does the conversion to XYZ color space. Now do the exact same thing to Node 3, except this time, do the conversion back to REC709. Now that you’ve done this, you’ve essentially done the color space round trip, and to get an idea of what the “Before” and “After” images look like, you can simply hit OPT/ALT and D to turn the color space nodes on and off, and get an idea of exactly what is going on with the luminance. Now, you can simply make any adjustments you need to make to Node #1, so this way when the conversion happens, the “re-converted” image will match more of the original look, that it would have if you had left it alone. One thing that is exceptionally important for me to point out is that once you have your image color corrected the way you want, taking into account the shift if luminance, is that you’ll want to remove the LUT’s from your video as, believe it or not, R14 will automatically add the XYZ LUT back onto our video, when we do the export to JPEG 2000 towards the end of the article. That’s right. As part of the export process, this step is done automatically, this is why it’s exceptionally important to remove the LUT, as you don’t want it added twice.

Alright, that takes care of my video, now what about my audio. Many people don’t bring their audio into R14, as they figure that since it was fine in their NLE, it will be fine here. That, for the most part, is true, but for me, I like to make sure that all my audio lines up and is in sync, and the best way to do that is to bring it around for the R14 process as well. AND, since we are doing a frame rate conversion, as well, I like to make sure that my audio follows the same pipeline as my video. Something else that’s exceptionally important for me to mention, and that is that BlackMagic Design has drastically changed how Resolve handles audio in this release (Fairlight), so if you’re reading this article, and using a different version of R14, this section might not make a lot of sense, so keep that in mind.

The first thing that I normally like to do with my audio is to “unlink” it from the video, and that can simply be done by right clicking on the audio portion of my clip, and simply hitting “Link Clips”. The next thing I like to do is to make sure that all my audio tracks are “Mono”. Remember, even though we are talking about a 5.1 audio mix (CH1:L CH2:R CH3:C CH4:Lfe CH5:LS CH6:RS), this is not one 5.1 audio clip. It’s six mono channels that make up the six channel 5.1 mix, so technically, each of these tracks is Mono, and we’re going to make sure we set them back to be Mono, so when we output, that’s what we get. The next thing you’ll notice is that beside each of the audio tracks, you’ll notice a number like 2.0 or 5.1. This represents the type track your audio is on. For us, 1.0 or Mono is what we’re looking for. Simply right click on the on the left side of the track itself, and select “Change Track Type To”, and select “Mono”. You’ll notice your track ID changes to 1.0. Do this for all the tracks, and then you’re ready to export your 5.1 audio as a single audio track containing your surround mix.

EXPORTING

Alright, here’s where we get our JPEG2000 image sequence, as well as our 5.1 audio set up and ready to go. Please keep in mind that I am aware that you can export directly for EasyDCP right from within R14, but I’m not going to cover that in this lesson. We’re going to save that for the actual DCP creation article(s). Okay, let’s get started. Head over to the “Deliver” tab, and the first thing you’re going to want to do is to set an output location for where you want your audio and JPEG2000 image sequence to go to.

IMAGE

Once you’ve done that, we’re ready to set up our video and this is where, in many cases, things fall off the rails. The Format and Codec drop downs are pretty self explanatory. We want JPEG2000 as the Format, and you’ll notice that as soon as you select it, the Codec immediately changes to 2K DCI, and most people think that’s fine, and they continue on with the output process but, if you happen to actually drop down the Codec menu, you’ll immediately notice that there is actually a codec for DCI FLAT, SCOPE and FULL, which means that you do need to set your codec (once you’ve selected JPEG2000) to match the raster dimension of the project you’re working on. In our case it will be DCI FLAT.

Something that I also want to point out is that if you are working from an “editing” master, meaning you’ve cut all your footage in R14, and are now ready to export, you’ll want to select “Single Clip”, which is the default export type. You will also notice that once you select JPEG2000 as your export type, it will immediately disable your audio export, which is fine for now. We’ll come back and take care of that in a second. By default your timeline will default to the maximum bitrate of 250 Mbit/sec (which is what we want), and your timeline will also have a frame rate of 24 fps. You can ignore the Advanced Settings, as we don’t need to set anything in there, for the purposes of making our DCP. Okay, Let’s head to the “File” tab to give our export a name, we’ll call it “Main DCP Waterfall Export”, and we’ll add this to the Render Queue.

Since R14 doesn’t like to export it’s JPEG2000 sequences with audio, we’re going to do this as a two step process. Head back to the video tab, and deselect “Export Video”. Now, the audio tab becomes active again, and we can select it, to set up our audio for export. Again, because we’re using R14, this step is a little different than it would have been done previously. In the Audio tab, we’re going to select WAVE and Linear PCM as our Format and Codec respectively, and we’re also going to make sure that we keep out bit depth as 24.

Now here’s where things are a little different than in the past. You’ll notice that there’s an “Output Track” drop down option below the Bit Depth. By default it’s set to “Main 1 (Stereo)”. We want to take the tracks that we made Mono in our timeline, and export it to one clip, that we can then take and import into our DCP creation application. With the layout the way it is now, we’ll be exporting one stereo clip. What we want to do is to take that Output Track (1), and assign it to the first audio track in our timeline, by dropping it down to “Timeline Track”. You’ll notice immediately that R14 defaults to choosing track 1, and it’s identifying it as Mono, which is exactly what we want.

Once you’ve set up all your tracks (one through six), you can add this export to the Render Queue, and you’re all set to export both your video and audio for DCP creation.

That’s it! Your work in Resolve 14 is done, but before we wrap up, there is something that’s important for me to point out. Assuming that you’re not using a DCP export option in an application like Media Encoder, Premiere or even Compressor (for all you FCPX editors out there), you are going to need to use an intermediary application like R14 to do your conversion to not only JPEG2000, but also to XYZ color space. To be honest, Resolve is my go to application for doing this, and I use it on every DCP project that I create. If you’re not familiar with working with Resolve, or this write up seems a little complex, there is a way to do this technique inside of Adobe’s After Effects, which we’re going to talk about in an upcoming article. For that technique, a third party plug-in is required. It’s old, but it’s free and works in both After Effects and in Photoshop as well.

And last, but certainly not least, I’ve been getting a lot of people commenting on these articles in regards to what I’ve been saying about taking your DCP to a reputable post facility to check your DCP, and many people have been posting (and sending me e-mails directly), telling me that that is not necessary, and you can just check it on a computer, and you’re good to go. Please, don’t do that. The whole point of taking it to a facility to check it is to make sure that, not only does it work, but so you can sit down, and watch it to make sure that it looks and sounds exactly the way that you expect it to look and sound. You want to experience your project, like the audience will experience it. Taking it to a facility will get you that, plus let you check to make sure that the DCP ingests into a playback machine properly, so you have piece of mind know that when that DCP is sent out to theatres, it will playback exactly the way you expect it to. In our next article, I’m going to walk through the process for the last of the big NLE’s, and that is FCPX, so look for that article in the coming weeks!