David Bach is a post audio professional and an expert in dialogue editing and ADR recording (dialogue replacement) for Hollywood blockbusters as his work on Dune, Dunkirk, King Richard, and many other great films attest.

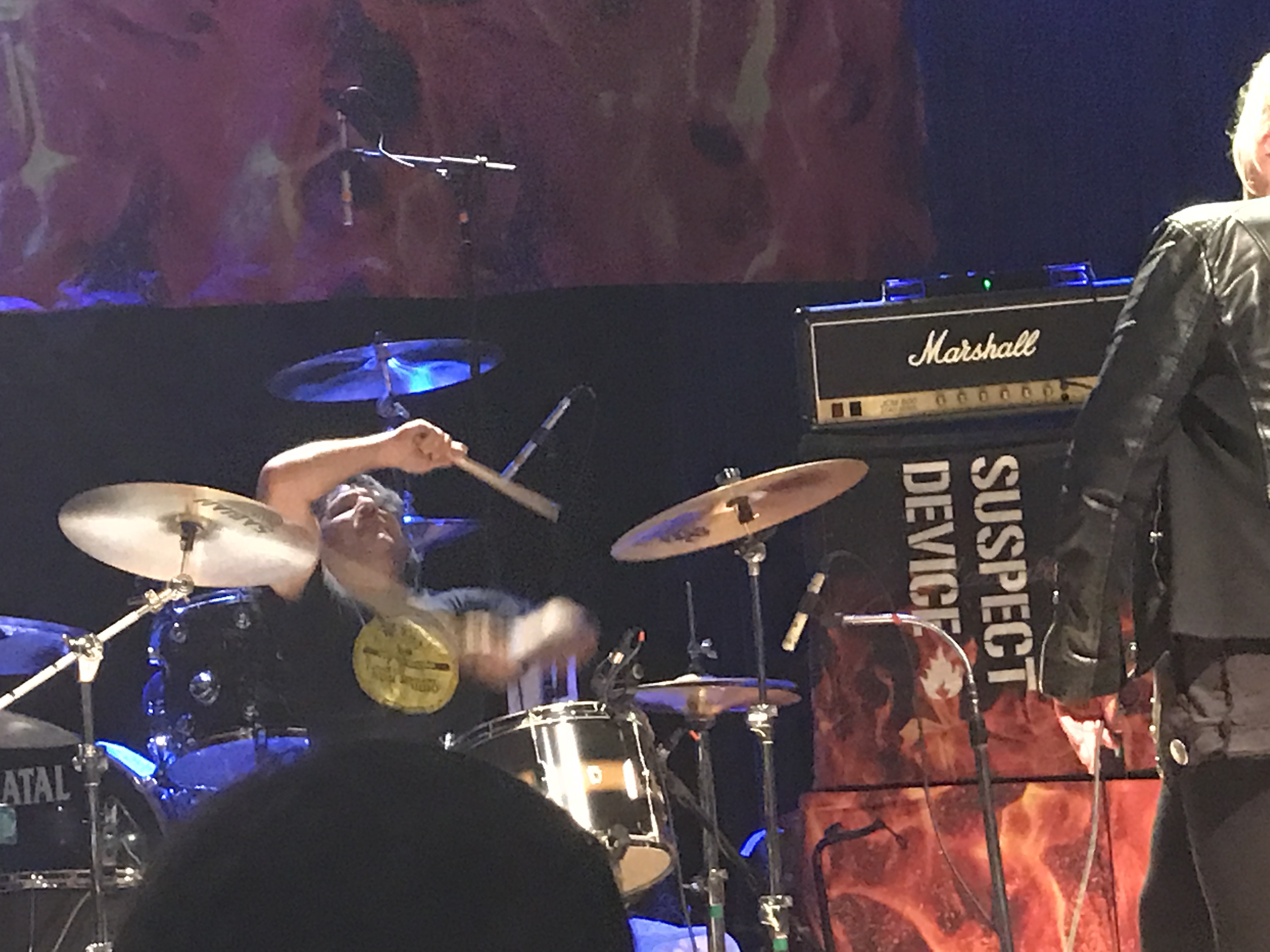

Like so many who work in the post audio field, David is a musician. David grew up in the Bay Area of California and was inspired as a drummer by Keith Moon of The Who and Stewart Copeland of The Police. He has played and toured as a drummer for many fantastic bands over the years and he attended college at Berklee College of Music after high school in San Francisco.

Although still keeping very busy these days with film and music during this horrible time of COVID, David found a few moments to discuss his career with me.

WOODY WOODHALL: Let’s start at the beginning. You attended Berklee College of Music, so music was your start in the post audio world?

DAVID BACH: Music was the starting point for almost everything in my life. I began playing drums when I was 10; joined Middle School Jazz band and then played bass in a San Francisco punk band at 15. A few years later, during my first recording session, our band’s producer Dan Levitin (later a neuroscientist and the author of This Is Your Brain on Music, et al) recognized how serious I was about my drumming—and the engineering process. He recommended Berklee at the time, but I took a few more years following the dream of rock stardom before I enrolled. I started off as a drum performance major, but then switched to production. That’s where I met the earliest incarnation of ProTools.

WW: Early on in your film career you were a music editor and a sound effects editor. What started the transition to focusing on dialogue?

DB: When I moved to Los Angeles, my intention was to produce music, but my first day job was as an editorial P.A. at Walker, Texas Ranger. That led to a job as a temporary post coordinator at another television series and then on to a machine room assistant and cable maker for the show’s non-union sound house. That’s where I met the sound designer and re-recording mixer, Elmo Weber and started to learn the basics. My first job as a fledgling sound editor was at Brasher Sound which served as launching pad for many of my peers in the business. Turnover was high as people graduated to studio work, so you could find yourself wearing many editorial hats over the course of just a year or two. At a low budget sound house in the 1990’s, you got your sound effects from a very limited library of pre-existing recordings. I was already getting sick of cutting the same car doors and gun shots. I was intrigued by how the dialogue editing process could serve the narrative (in a talkie) in a way that car crashes couldn’t. My first film as dialogue editor was the wonderful indie, Gods and Monsters, starring Ian McKellan. I never looked back.

WW: You accelerated to a supervising sound editor quickly and after that as a rerecording mixer as well. Is there one craft that you enjoy the most?

DB: I enjoy films where I work closely with the director and picture editor, so for those I generally would be the supervising sound editor and rerecording mixer.

WW: When working specifically in dialogue can you describe the process of getting the recordings, working with the supervising sound editor and director and producer in crafting great sounding tracks?

DB: I’ve found that the dialogue editorial process depends a lot on the director and the genre of the film. For Sideways and Nebraska, I knew that Alexander Payne was very attentive to production sound to all-but-eliminate the need for ADR, so I focused even more than usual on working with all the production tracks when additional clarity was needed. Tommy Lee Jones is a stickler for precise enunciation, so when we first spotted tracks for The Homesman he wanted to tag a lot of the dialogue for re-do at an ADR stage. So, I brought him back to my studio after an editorial pass to take a second listen to how many fewer ADR cues we needed. When he still had notes about ADR needed for his own performance, I suggested he try re-recording some of the cues as we sat at the console so we could have at least a temporary fix. He was doubtful, but within 15 minutes, he was comfortable pulling over the microphone to add efforts or replace a word that bugged him. This allowed us to focus on the forest, since the trees weren’t bothering us anymore. As an almost polar opposite, Christopher Nolan for Dunkirk and Tenet, did not prioritize dialogue clarity, finding it unrealistic if you can understand everything someone is saying on screen. My only strategy was to prep many alternate tracks with varying ranges of intelligibility to give the mixer a range of options if my best guess didn’t align with the director’s aesthetic.

Of course, working on action, giant robot, or super hero movies is very different for dialogue editorial, since practical special effects and stunts drown out so much production dialogue. During the filming of Suicide Squad, the picture editor was having an impossible time with the recorded dialogue for the assembly cut. So, I was sent to the Toronto set for the last three weeks of the shoot to clean up tracks for the editors and to shoot a round of ADR while the actors were still in character and, in some cases, still in costume.

In the most rewarding collaborations, the director communicates his vision and idiosyncrasies to the supervising sound editor, the dialogue/ADR editor provides the mixer with the resulting tracks in their preferred format and the mixer provides the director and producers with their best options.

WW: Like most of us in post we use iZotope’s RX suite of restoration tools daily. Can you talk about how you decide what bites or situations to process before handing off the tracks to the rerecording mixer for the final dub?

DB: I think the most import thing is to be able to unwind any noise reduction – it’s so hard to tell how it will react to the overall soundtrack until you hear it against the backgrounds and music. Sometimes I’m still surprised how little noise reduction you might need once the music is in there. Other times it’s the opposite.

WW: You have extensive expertise in ADR, can you talk a bit about that process, its challenges and how you send the tracks off to the dub stage?

DB: The ADR needs are so different for each project, but one thing I’ve noticed is clear – if the director and actor believes that it’s necessary, then we can get a seamless performance. Whenever possible I like to have the actor take ownership of the process, as in, going deep into the track to hear how we can improve it and have them make the decisions on direction.

WW: You’ve worked on major Hollywood features; can you discuss anything about the differences between those projects and smaller indie films?

DB: I’ve been lucky to be able to balance big budget studio pictures like Dune, Tenet and King Richard, where I’m one contributor in a very talented team, with indie projects that I supervise, loop, pre-dub and often final mix from my home studio—including the documentaries Walking Man and Soros and features such as The Homesman, directed by Tommy Lee Jones which went to the Cannes Film Festival and Dean by Demetri Martin which won the Tribeca Film Festival.

In many ways, the main difference is in scale. For Dunkirk, it was amazing to be able to record Group ADR on the WWII warship HMS Belfast in London harbor. We had the entire Warner Bros. lot to recreate the sounds of the angry Iranian crowds for Argo. However, for Dean, when Demetri wanted a last minute addition to the score, he brought Mark Noseworthy from The Magnetic Zeros over to my studio to watch the nearly mixed film. We set up mics to capture his first draft on guitar. The following day we recorded the final tracks in my studio with guitar and cello.

WW: Recording, playing and touring with great bands as well as taking on these huge Hollywood productions must keep you busy all the time.

DB: I’m trying hard to balance my music and film work and still excited about both! There’s always new gear/plug ins/methods and instruments to get better at and as long as I’m still learning new stuff, I’ll keep at it.

Woody Woodhall is a supervising sound editor and rerecording mixer and a Founder of Los Angeles Post Production Group. You can follow him on twitter at @Woody_Woodhall