Editor’s Note: “28 Weeks of Post Audio” originally ran over the course of 28 weeks starting in November of 2016. Given the renewed focus on the importance of audio for productions of all types, PVC has decided to republish it as a daily series this month along with a new entry from Woody at the end. You can check out the entire series here, and also use the #MixingMondays hashtag to send us feedback about some brand new audio content.

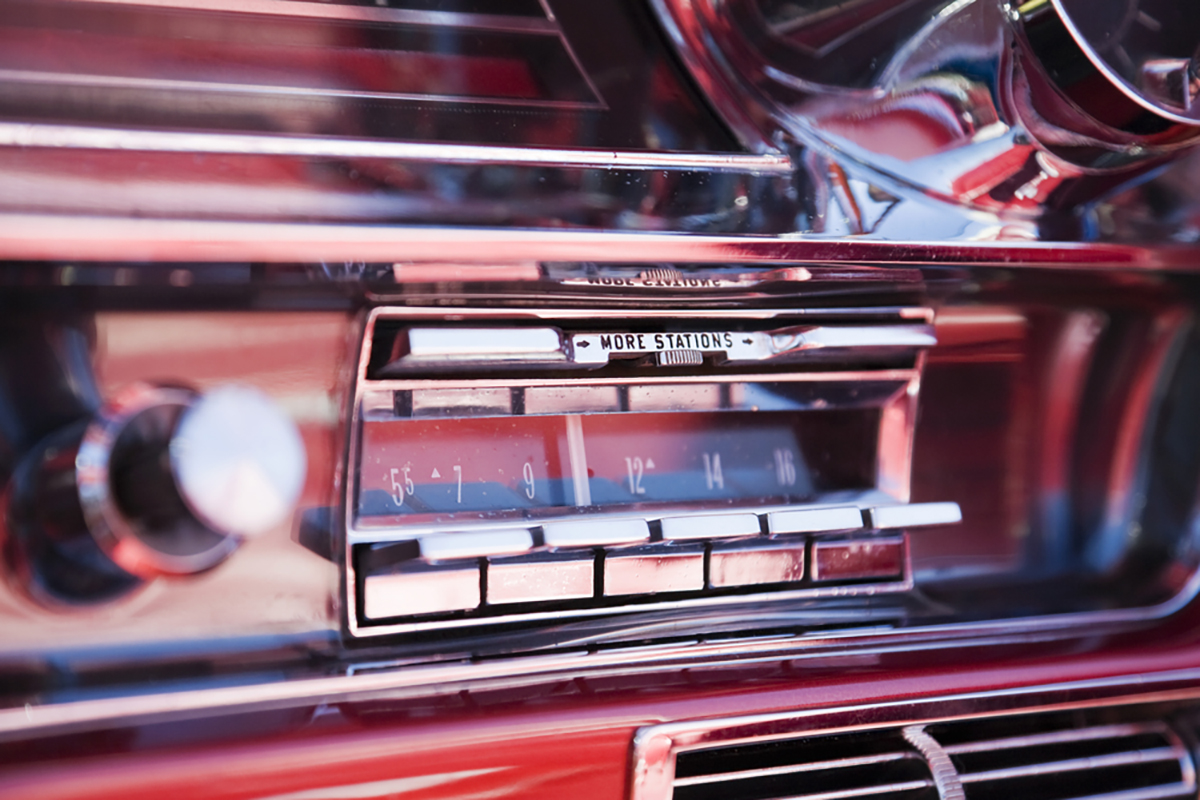

In terms of sound for picture, diegetic is defined as: sounds that originate within a given scene. All of the typical sound elements seen in a scene would be considered diegetic, such as the dialog and the action. Diegetic sounds don’t need to be sourced exactly by the scene, for instance, lights on a street might flash by and a siren is added in post. These sounds, along with birds or crickets can also sometimes be called extra-diegetic, implied by the scene, but perhaps with no close-up of a cricket or a bird calling. Being sourced from the scene, it is considered a diegetic effect. Music can also be considered diegetic if, for instance, it is playing on a car stereo that the characters react to. Another example would be bands or musicians playing within the scene.

Another mostly correct definition of diegetic sound is that these are sounds that the characters on-screen can hear and are reacting to. If there are cars racing, we might hear screeching tires, police sirens following and perhaps people reacting. I have to use the terms “mostly” or “typically” since there are no hard and fast rules for any of this.

The use of L and J cuts can contain diegetic sound to the scene that they are relating to, they are a foreshadow or a lengthening of an upcoming scene or outgoing scene. A J cut of audio is when we can hear the incoming scene’s audio before the scene is actually cut to. An L cut is the same idea but at the tail of a scene, we continue to hear the sound of the prior scene as a new scene appears. However, in either of these cases, or both, diegetic sound inherent to the relevant scene can be used in those cuts.

Non-diegetic sound effects are used endlessly in television programming. All of the whooshes, dings and wipe sounds are outside of the scene. They are there to serve the transitions of the editing, or the motion of specific graphics, and not the story content itself. Occasionally, feature films may venture into that type of non-diegetic sound. Edgar Wright films do this expertly, both with sound and with picture. Non-diegetic sound effects are often so artfully created, edited and mixed, that they almost seem to be a part of a film’s score creating tension and emotional impact.

Horror films make great emotional use of non-diegetic sounds. Howling winds, unseen birds calling or just straight up weird sound designs are used to inspire fear, trepidation and scares. “Did you hear that?” “No….” Sound up, and cue the screams. Sci-fi, of course is filled with non-diegetic bleeps, bloops, rocket ship and alien landscapes.

Many influential directors make use of non-diegetic sounds for exactly this reason. David Lynch is a master at this sort of sound design approach. The spectacular work by Alan Splet on “Eraserhead” is just the first of many examples in Lynch’s oeuvre. Have a listen to Lynch, Alejandro Inarritu, and Stanley Kubrick films, decipher the non-diegetic sounds, and see what emotional response you have to them, then see if there is a use of this sort of soundscape in your own work.

Inarritu’s most recent feature film, “The Revenant” made a remarkable use of non-diegetic sounds. In fact, I would suggest to anyone with a keen interest in sound for film to specifically study the sound of that film. The sound design, the score and the sound mixing weave an astonishingly effective soundscape, unlike most Hollywood features ever released. It will take quite a number of listens, (I know, I did it) to try and decipher which sounds are score, which are effects, which are Foley and dialog replacement. Frankly, it might be an impossible task! It is a masterful blend of sound and score, the sound design and location audio, and was appropriately nominated for both sound editing and sound mixing for Oscars at the Academy Awards. I have an in-depth look at creating the sound for the “The Revenant” here.

One of the supervising sound editors and supervising sound designers on “The Revenant”, was multiple Oscar winner Randy Thom. Randy is the Director of Sound Design at Skywalker Sound, and has contributed his sound artistry to many classic films. Randy speaks of a unique quality that was very important to Alejandro regarding the sounds for “The Revenant” –

“He has a wonderful word, cacayanga, a kind of noise or complexity, the source of it is not readily apparent. He would often ask for noise that isn’t related necessarily with anything that is showing on the screen.” In a perfect description of the idea of non-diegetic sounds Randy says, “I think that when Alejandro calls for a little cacayanga, a little uncorrelated noise, I think that he is trying to make it more like the real world – when unpredictable things happen and it’s complex and everything is not explained or linked to what you see on screen.”

All of us who design sound for film should take a cue from Alejandro Inarritu and find just a bit of cacayanga to enhance our scenes.

This series, 28 Weeks of Audio, is dedicated to discussing various aspects of post production audio using the hashtag #MixingMondays. You can check out the entire series here.

Woody Woodhall is a supervising sound editor and rerecording mixer and a Founder of Los Angeles Post Production Group. You can follow him on twitter at @Woody_Woodhall