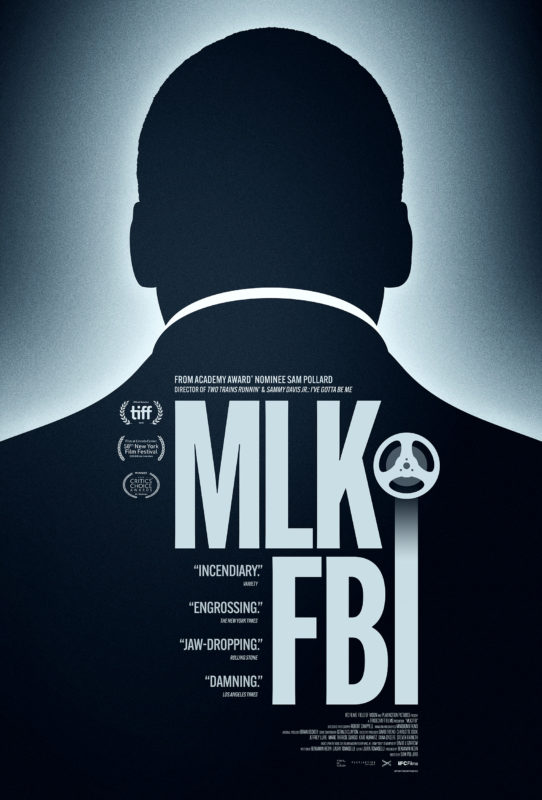

Recently I was given the opportunity to interview editor Laura Tomaselli about her fantastic work on the new documentary MLK/FBI directed by Sam Pollard. What follows is the transcript of that conversation, lightly edited for clarity (no one wants to read me say “um” 40 times).

Essentially the entire doc is made of archival footage. How many hours of film were you working with?

Laura Tomaselli: Oh my goodness. I think I did a tally at some point and it was over 300 hours, but I remember thinking before I did that tally that it would be more than that. It was quite a bit.

Oh wow I was assuming it was going to be like, thousands. What were your storage requirements? How did you organize all that? Also, was there a script that you had written or like a paper edit that you had ready and you knew you wanted to get specific clips or was that all built as you went?

We definitely were building as we went. At some points almost dizzyingly. And obviously what we all were living through in 2020 made it pretty difficult for me to have an AE on this, because my archivist (Brian Becker) was also working remotely, and having to coordinate with that many people would have been just tricky for me while I was trying to like work through it day in, day out.

What’s funny about storage requirements, it was really small for such a long time because I was working with the watermark archival. And so like one of the funniest points in this movie was when all of that turned into like the beautiful [full-resolution] archival, but for a really long time a lot of my source of was like 360p ya know?

I set our master file directory for archival handoff, which was on Dropbox as a watch folder, and created a droplet that would automatically transcode all the stuff he dropped in there, which would be a bazillion different sizes of bazillion different historical codecs and would encode them all to a loose kind of 1080p type thing. And it would, you know, neatly do that work in the background while I was trying to edit the movie, you know?

Oh wow that’s a great workflow. So you didn’t need too beefy of a computer or anything then?

We do have a have a pretty spec’d out iMac Pro, but to be honest because we weren’t using the footage of the interviews until the very end so it just wasn’t a very heavy project. I had a bazillion audio tracks, you know, but it was still pretty light.

Was that purely a creative choice to only put the footage of the “narrators” at the end?

Yeah. I think Sam and I were both inspired by a lot of the archival-only docs, you know? There’s a great old one of King that won the Oscar called A Filmed Record: From Montgomery to Memphis, and that’s like our direct predecessor, but I think he also really liked The Black Power Mixtape, you know, there’s Amy there’s Senna there’s Mike Wallace, stuff like that, so I watched a lot of those. We really felt like telling the story through archival so that it was fully immersive.

So you were the only editor, no remotes or anything?

Yeah. My husband who’s a really talented director, by virtue of us being quarantined together ended up sort of working in tandem with me a little bit, almost as an AE when I needed it, but I technically didn’t really have an AE on the project either.

That’s a triumph of work. I’ve got to hand it to you.

I think the real necessity, obviously, like I’m getting in all this archival footage trying to put it together, all at the same time. And my head was exploding without an AE. So like, figuring out the watch folder transcode thing was so key.

How did you organize that footage without a strict “script”? Was there a paper edit or did you already know what selects you wanted to pull or…

I’ve tried every organizational method that editors can use. There was a point with index cards for me, there was a point where we did do a script after we had a first pass that was a very long, rough, like… three-hour pass. That was the first time we got that transcribed and had a script and kind of really worked in that way. We worked almost completely chronologically with the archivist working alongside. It was a very useful way to cut something and then we kind of jumbled it all together, you know, after the rough cuts.

Sure. So were you going off of the news reels or like, FBI documents and then trying to explain them in context or… where did you acquire the framework of the story?

Ben had been the producer and the co-writer on this. He found this book called The FBI and Martin Luther King Jr by David Garrow so [MLK/FBI] is actually a jump off of that. In terms of finding the story it was really like whittling it down on all sides, you know? It was both what we had from these like really great interviews and then Brian our wonderful archivist would pull something in and we would just be like “Oh my God, this has to be a thing”. You know, it was kind of coming at us from all sides, if that makes sense.

Did you have any clips that you knew you were going to use that you had to find, or was it all like you had the audio and then built everything around that?

I think we knew that we were going to use the Riverside church speech Beyond Vietnam, and I think we knew that we wanted to try and use the Mountaintop speech, the night before he’s assassinated… aside from that [the interviewees didn’t have] a totally encyclopedic knowledge of everything so it was like a process of discovery for a lot of it.

I will say though, the parts where we’re talking about like FBI iconography and training and all that stuff, and especially where we’re riffing on some of the classic, you know, communist kind of propaganda Red Scare movies… Sam’s film knowledge is like completely encyclopedic. So while we were very much finding these expositional pieces or just like really special pieces that we love of King, Sam was instrumental in being like, “you need Walk a Crooked Mile” you need, you know, all these other films and like even the FBI TV series, he knew that he wanted those pieces. So while there was searching and some of the archival, like there were these other pieces that we really knew we wanted in there.

A friend of mine is actually in the middle of editing a feature documentary, so I texted him and asked if he had any questions for you ‘cause he’s pulling his hair out working alone as well. He wanted to know what your timeline looked like; were you working in Reels, one big long timeline, what was your organizational process there?

I think that so much of making this kind of a documentary for me was coming up with these sections that I felt really good about. It was never anything quite as strict as reel, but I knew that maybe I wanted to connect one thing to, you know, a plot point, maybe 20 minutes down the line. And that would be something I would break apart if I knew I really wanted to get into it.

I duplicate my sequences obsessively only because I’m very indecisive. I’ll be hitting a wall and hitting a wall and be like “maybe if I try this other thing, it might really work”…

Oh yeah I’m a big fan of versioning.

Oh my god you have to version! You’ve gotta duplicate and be like “pre crazy music change”. Or I always, I leave these little breadcrumbs for myself so that, you know, if I’m just like “Oh man, I really took a wrong turn here” I can go back pretty easy.

Speaking of music, the composing is really excellent. Was there a composer, was that all found music, what was the deal there?

Gerald Clayton was the composer there and he’s really, he’s just wonderful. He’s like a, multi-instrumentalist super talented, like jazz pianist. He even worked with us on the pitch in like, 2018? He was in on the initial meeting, like when I met Sam for the first time and Gerald was there to have the first conversations about what it was gonna look like. So, yeah, he was really instrumental.

I worked a lot with him because he would record full pieces and then I would sort of go back and forth in terms of arrangements, like in the Hoover sequence maybe 13 or 20 minutes in, we had a song that was recorded with a whole bunch of instruments, but then when we put it into the cut we really paired it back [to a more bass-heavy vibe] and had it built, you know, as needed for the arc of the scene.

How were those sessions done? Were those also done remotely?

He actually didn’t record to picture, I cut to his music. We always sort of felt like it made sense to have him do something that felt right and that we would sort of kind of nip and tuck a little bit to make it work for us.

Did that make it easier on you to a degree? I know for smaller gigs finding the music is the hardest part but once you’ve got it, editing can be a breeze.

It’s very much a Pandora’s box. It’s like, once you get under the hood and start being like, “maybe I’ll take out this guitar line” or add a guitar line, you know, you can fall into these really intense little moments of tweaking too much, but it was incredible to be working back and forth with him. If I was ever stuck he would always be able to customize something which was great because we could really make it fit with the scenes that were evolving at the same time.

There was a lot of motion graphics stuff. Were you doing all that yourself in After Effects?

Thankfully no [laughs] can you imagine if I was though? Oh my God.

There was a period where I would rough some stuff out. I’m not a pro in After Effects let’s just say that, so I would block some stuff out, like just in terms of what we needed it to look like and I would go through the documents, pick out the highlights and all that stuff and lay it out and then give it to [Mind Bomb Films] and they would really refine it.

What made you choose Premiere?

Funny aside: my first internship out of school was at Avid Technology in Massachusetts. My first real job in New York was as a tech at Postworks, so I have Avid in my background, but creatively, hilariously enough, I think that I first really learned to cut by myself on Adobe and I still feel the most comfortable in it. I know my way so well around that program that I know it’s adaptable enough to do kind of whatever I needed to do.

I’ve never used Avid, but I’m sure all the wacky codecs you got from Archival probably were easier to manage in Premiere.

Oh my goodness. I can’t even imagine. I think Avid would be like “no, thank you”. I don’t even think Avid would let that in the door. Some of the stuff I would hit “get info” on and be like “I’ve never even heard of this before”.

Were there any things that you learned during the process of editing this that you would want to pass on to other editors that sped up your workflow or made things particularly easy, or you wish you knew before you started?

I hope that this is a piece of advice that is useful to anyone else: This is only my second feature. It was a lesson in letting go of some of the perfectionism you need in short form, in the early stages.

When Sam and I started working together, I was so nervous when he would come in and watch my cuts. He just had to be like “relax, no one gets it right on the first edit” you know? Especially with a film like this, I was really trying to be like “maybe if I try really hard, it’ll be perfect the first time” and there’s just no way. Especially over the last year, it was just cutting myself some slack and, you know, being more experimental and being… I guess a little bit more vulnerable and asking “is this a good idea?” You know? And they were all great to collaborate with in that sense. If all that makes sense.

Were you doing any Mixing or “Color” in Premiere yourself? That was probably sent out as well right?

It was, yeah. For this we worked with RCO on color and the frame rate conversions and upresing all this footage that, even when we got the masters, you know, might be 720p or something. They were instrumental in really bridging a lot of those like technical divides for us.

I think beyond just resizing and de-noising the footage, [they did great] even matching the tone and level of contrast and level of noise and grain between shots. Cause there’s a lot of sections where I think that like, maybe someone like you, but maybe not everybody knows that there’s shots pulled from eight different things in a row and smoothing out the differences.

Were there any things that you had to cut that you were kind of in love with and were bummed you had to get rid of?

For a long time Merv Griffin was on the cutting room floor. The only other part I will say like, from folks that’re my friends that have seen it everyone just said “there’s so much information in it”, you know?

There was a version of this, when it was really chronological, that started after right after World War II. It really went into American paranoia, calming the Red Scare and McCarthyism and that whole thing. It was really fun footage because it was a lot more of [the movies and shows we pulled from], which I think is just really fun to watch ‘cause it was so genre-y, ya know? I think we were all sad to lose that, I know Sam loves those movies, but ultimately we were just like “at some point we have to pick when this movie starts and it probably shouldn’t be in like 1940-something” ya know?

I assume you have kind of have to hope that the audience has enough knowledge that you don’t have to explain, for instance, the Red Scare. I mean If you want to really explain the content of this whole documentary, you could start 150 or 200 years ago and make a whole series.

Dude oh my God, you have no idea. I think that was one of the biggest challenges with archival is that you had to really check yourself. Cause like every day Brian and I would be going back and forth and he’d be like, “Hey, what do you think you need?” And like Ben and Sam would also be giving us things but like if I had it, it was really interesting to -to your point- go into any one of these other avenues and start it earlier, you know? There’s a whole other section about Chicago and the Watts riots that is cut from the film, but feels almost identical what’s happening now in America, you know? It’s Sam Pollard more than anything like, having a director that is an editor is just like a dream, you know?

Oh for sure. I’m a DP, but I’ve often had to edit my own stuff and it’s made me a better DP. I can only imagine that being an editor makes you a better director and vice versa.

Absolutely.

Well, I believe that’s about all the time I have. I really appreciate you spending it with me and answering those questions for me.

Likewise!