One of my favorite clients recently pitched a project that requires shooting high-speed footage at 1000fps. To help them sell the concept I shot some tests comparing the RED ONE at 120 and 100fps to the Phantom HD Gold at 1000fps.

Chater Camera kindly let me aim both cameras out their shop’s roll-up door and roll some footage. Here’s Jay Farrington, DIT extraordinaire and co-owner of Chater Camera, waving a piece of bubble wrap out front of his facility. This was shot on a RED ONE in 4K HD at 24fps:

I think you’ll agree with me that Jay is poetry in motion.

The RED ONE will do 100fps in 2K 16:9 mode, so let’s see what that looks like:

Not bad. But 120fps is where things get a bit more interesting, so here’s the RED ONE in 2K 2:1 mode at 120fps:

The RED will do 120fps only in 2k 2:1 mode. The slight letterbox shows the reduced image area from 2K 16:9 mode.

Notice how each shot gets tighter. I’m using the same lens for each of these but the portion of the sensor used decreases as the RED’s frame rate moves beyondcertain limits. The frame rate is determined by a number of factors, including how fast data can be read off the sensor and throughput, and the RED seems to solve those problems by reducing the active area of the sensor and storing 2K data instead of 4K. The RED’s 2K modes are slightly softer than 1920×1080 footage from other cameras, but with a bit of post sharpening 2K can look pretty nice.

The annoying bit is that the depth of field appears too deep when looking through the center of a lens, because the focal length of the lens remains the same but the angle of view tightens. The result is the kind of depth of field you’d see when shooting 16mm film or with a 2/3″ video camera. Worse yet, you have to use a really wide lens for wide shots because an 18mm lens will give you the angle of view of a 35mm lens when rolling in 2K mode–but the depth of field will be the same as an 18mm lens!

The Phantom doesn’t have this problem because it uses the full sensor frame when rolling at 1000fps. Beyond that it has to use less of the frame for the same reasons that the RED does.

Here’s the Phantom HD Gold at 1000fps:

Note that I saved the most graceful speed for myself. There’s a reason for that: at 1000fps the most interesting motions are the most spastic, which works well for me.

The reason you see the data overlaid on the image is that we recorded the Phantom’s HD-SDI output to ProRes using a KiPro data recorder. This is a popular way to use the Phantom as it saves time and money in post. The camera normally records data to a Digimag, which has an astounding number of connectors on its underside to facilitate the rapid transfer of image data. It’s easy to play back clips from the camera, but not so easy to get the raw data off the Digimag: the rule of thumb is that a gigabyte of raw Phantom data takes a minute to transfer over gigabit Ethernet, so downloading a 256gb Digimag will take close to three hours. Then it has to be debayered (Glue Tools is a popular app for this) and color corrected.

It’s common to trim the clips in the camera so you’re keeping only the best part of each take, or simply delete bad takes, in order to minimize raw data download time.

Or you can get the look as close as possible in the camera, record the playback output–without the data overlaid–and walk away with a ProRes file ready for editing. That’s what we’re going to do on this shoot. We left the telemetry on for this test because we wanted to impress the client a bit, and I thought it would be useful to show you what kind of information the camera outputs. You can see the current camera state is displayed in the top left corner (“PLAY” for playback); the mag ID is in the top center, and the frame number is on the top right. The lower left shows the camera mode, which indicates that we’ve defined a 2k “stage” upon which we’re capturing a 1920×1080 frame; next over is the frame rate; the shutter angle is 180 degrees; the lower middle shows the timeline with the trigger point; I have no idea what “72s/72s” is; and “4351” is the total number of frames captured.

Although we originally captured 4,351 frames I’m only showing you about 1000 frames in this clip. That’s about one second of real time. The full clip captured four seconds of real time and plays back in a little over three minutes.

This camera has a 16gb buffer that is always capturing data: the camera is always “rolling.” Because of this you can set the trigger point–the point where you tell the camera to actually record the image, either by hitting a button on the camera or on the attached laptop controller–anywhere on that 16gb buffer timeline that you want. That long horizontal line on the bottom of the frame represents the Phantom’s buffer, and the little arrow underneath it indicates where the trigger point is set on that timeline.

At 1000fps the Phantom’s 16gb buffer can record four seconds of real time action, and you can trigger the recording at the beginning of that four second window, at the end (capturing the previous four seconds of data running through the buffer), or anywhere in the middle. If you are shooting a water droplet falling onto a surface, for example, you might set the trigger point 2/3 of the way through the shot: your reaction time might be a bit slow, so if you trigger the recording just after the water droplet impact then you’ll record 2/3 of your shot before the trigger push and 1/3 after. With any luck, assuming your reaction time is a little slow, you’ll capture half the shot before and half after the droplet impact.

During playback the trigger indicator moves along the timeline to show the clip’s current playback position.

For the project I’m about to shoot we need to capture three ten-second segments per spot–and ten seconds of playback time equals about 1/4 second of real time capture. So every action we shoot is going to have to occur over the course of 1/4 second.

Yikes!

Like most electronic cameras, I have the option of turning the Phantom’s shutter almost completely off (359 degrees, where off is 360). This buys me another stop of light, which is very helpful: at 1000fps, with the Phantom rated at EI 250 (which is roughly where the “sweet spot” of exposure is) and with no shutter engaged, I’ll need 833fc of light for a stop of T2! I normally light to somewhere between 20fc and 50fc for normal shoots, and I’m going to need about four plus stops more light for this job, with every additional stop doubling the amount of light. With a 180 degree shutter I’d need 1600fc of light! For high speed tabletop work that’s no big deal as you’re only lighting a set about 1′ square, but I’m lighting 16’x16′ and 20’x20′ sets containing people.

I’m not worried about blurry edges as and exposure time of 1/1000th sec. is pretty darned fast.

To determine how much light I need for “optimal” exposure at a given F-stop, I extrapolated using this basic formula:

EI 100 at 24fps and 180 degree shutter = 100fc at T2.8

For example, at EI 200 you’d need 50fc at T2.8; at EI 100 and 48fps you’d need 200fc for a T2.8.

If these kinds of calculations make your brain hurt, or if you just want to check your math, go get David Eubank’s excellent PCam application for the iPhone and iPod Touch. I bought my iPod Touch specifically to run programs like this.

Fortunately I won’t need 833fc of light overall: in a day exterior I can use bright spotted lights to create streaks of “sunlight” that are a stop or so brighter at 1600fc, and fill with 400fc or less. For night shots I can use even less fill. Fill light is going to be my biggest issue because I like my fill sources large, soft and mostly invisible. I’ll need to bounce or diffuse big lights to make that happen. Streaks of “sunlight” are easier as it’s not too difficult to spot in a 10k and aim it properly.

I’ll be using maxi brutes for most of the lighting, along with some 10k’s and 5k’s and some “firestarter” VNSP (for “very narrow spot”) tungsten PARs. (Walk closely across the beam of a “firestarter” and you’ll quickly discover how they got that name.) The PARs and the maxi brutes are great brute force lights but they have small filaments, and small filaments tend to dim a little bit as AC current switches direction. As a rule, anything less than a 5k tungsten bulb will appear to flicker at 1000fps when powered by alternating current, but maxi brutes and firestarters are cheap and efficient ways to light broad areas quickly so we’re renting a DC generator to avoid the flicker problem. DC power doesn’t alternate direction, so the dimming problem is eliminated. There’s still a little “ripple” in the voltage as we’re using a rectified DC generator that converts AC to DC, instead of a generator that creates pure DC current, so my gaffer checked with a DP who used this generator recently in the same way we are and he reported that he had no problems with flicker. (HMIs are right out as even flicker-free ballasts will cause the light to flicker unpleasantly at 1000fps. The max speed for HMI use is 120fps.)

I did a lot of homework to make sure I can do what I need to do with the lighting instruments I have available. Following Cinematography Mailing List owner

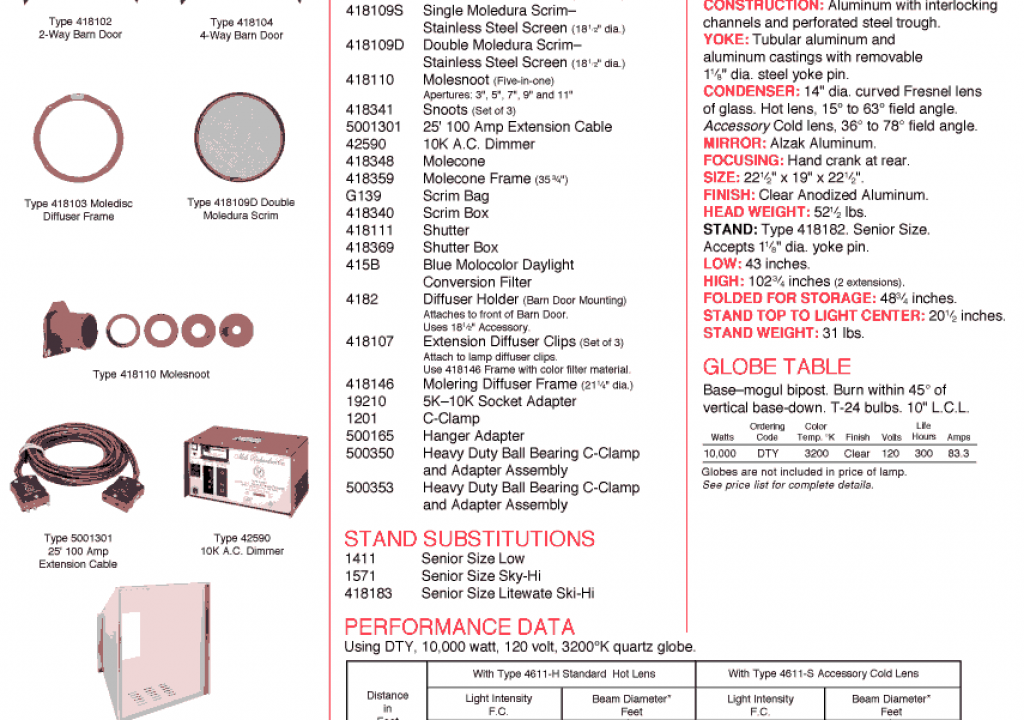

DP Geoff Boyle’s advice to “do the math” when lighting large areas, or lighting very small areas very brightly, I went to Mole-Richardson’s website and looked up some specs. For example, here’s some valuable information as to how much light their Baby 10k puts out:

The stage we’re shooting on isn’t that big, so knowing that I can get 3200fc out of that light at 20′ gives me a lot of confidence that it will give me the hot “sunlight” streaks that I want. I’ll be happy with 1600fc, as that gives me an extra stop of illumination and sunlight always looks better when it’s a little overexposed.

The 12-light maxi brutes that we’re going to use are similar to this Mole light:

Medium flood bulbs that give us 4400fc at 20′ will translate into a nice soft bright bounce source.

This shoot promises to be awesome, and I can’t wait to show off the footage. Hopefully I’ll be able to do so in a few weeks. Stay tuned!

Art Adams is a DP who works quickly no matter what the frame rate. His website is at www.artadams.net.