Digital filters are awesome for post image manipulation if you have enough bits to throw away. Glass filters, though, work at the highest resolution possible, in the camera head itself, and you’ll never have a better image to tweak than that.

A year ago I had the pleasure to interview Ira Tiffen, formerly of Tiffen, Inc., and Bob Zupka, currently of Schneider Optics, for a magazine article. Here, with a few tweaks and updates, is that article.

THE BASICS

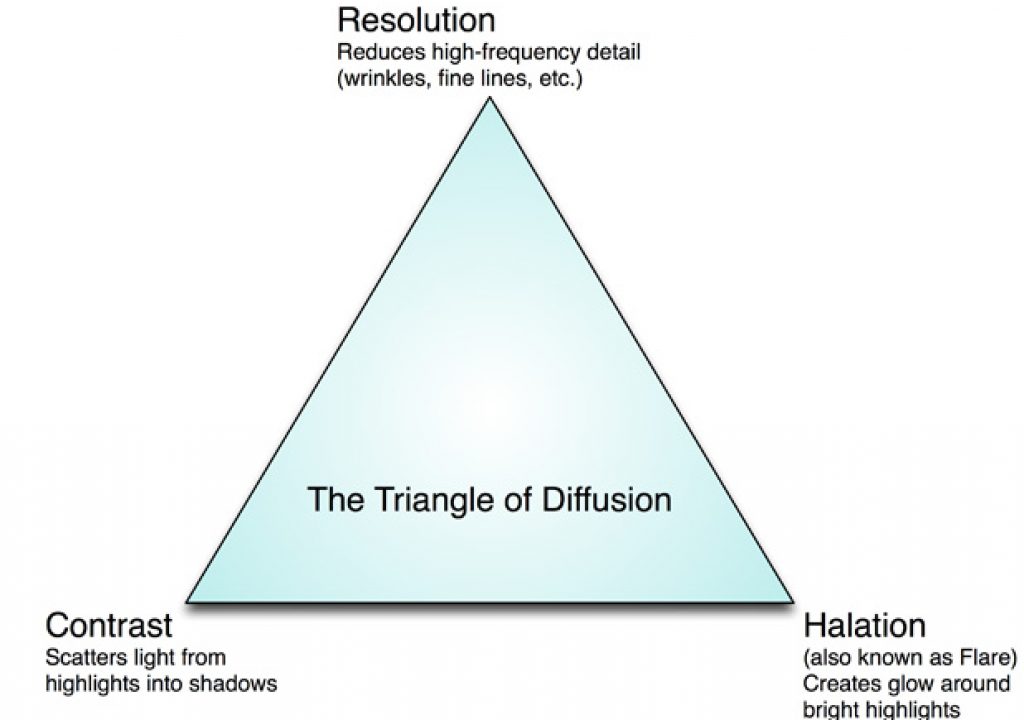

The class of filter most often spoken of, and yet the least understood, is that of diffusion. Twenty years ago, Ira Tiffen sought to formulate a methodology of classifying diffusion filters to make it easier for cinematographers to understand what a particular diffusion filter was doing, and to make it possible to guesstimate what another filter would do based on knowledge of a particular filter’s effects. He proposed numbering the three components that a diffusion filter affected, on a scale from zero to ten, and using those numbers as part of the filter name. The three components were contrast, resolution and flare.

Filters that reduce resolution are said to affect “high frequency detail.” To those of us who got A’s in English and D’s in Physics, that means areas of the image that contain fine detail are affected more than areas that contain coarse detail. Wrinkles are a fine detail, lips and eyes are a coarse detail. How much fine detail is removed depends on the strength of the filter used.

Flare can also be thought of as halation, or “halos.” Flare causes highlights to scatter, and the quality of that scatter determines a lot about how the filter is used. For example, a Tiffen Pro-Mist may only scatter highlights a short distance across the filter so the highlight appears to glow. A Schneider Fog filter would create highlights that spread a great distance, effectively distributing the halation across the entire image and creating an overall “fog” effect.

Contrast filters affect–wait for it!–contrast. These work off flare as well, but instead of creating halation in the scene they scatter the light into the shadows, revealing details in the darkest tones that might not otherwise be visible.

Tiffen’s system would have designated each filter with a three digit sequence that told how much of each effect was present in the filter. If, for example, a 1/2 White Pro-Mist had a score of 2 for reducing high frequency detail, 3 for contrast, and 5 for halation, it would be relatively simple to find a filter that provided roughly the same effect but without the halation (a Soft F/X filter, for example). While the system itself never caught on, the thought behind it did.

On page 2: the three aspects of diffusion…

THE DIFFUSION TRIANGLE

Zupka relates that he was taught to think about diffusion filters as falling somewhere within a triangle whose points were (1) reduction of high frequency detail, or resolution, (2) contrast, and (3) halation. “These three things are what every diffusion filter affects one or more of,” he says. “A Fog or Low-Con affects mostly contrast and also some resolution. Classic Softs or Soft F/X primarily affect resolution, with little affect on contrast and no halation. Pro-Mists or Frosts affect contrast and resolution, with some halation depending on the color of the diffusion (white, black, gold, etc.).”

Schneider has three basic types of diffusion filters, which Zupka describes:

“The Classic Soft is a very, very clean diffusion. It only affects very high frequencies in detail, with no effect on contrast level. It just affects very fine details, like wrinkles. The filter contains internal lenses that refocus the image off the image plane. The open spaces between the lenses pass a sharp image, while the lenses overlay a defocused image on top of the sharp image. Different strengths merely increase the number of lenses.

“Black Frosts contain black particles that diffract light around the particle, as well as scatter light a bit. Our particles are porous, like volcanic rock. Being able to see through the particle keeps blacks and dark tones from getting mushy, while diffraction and scattering contribute to the diffusion effect. This is different from Tiffen’s Black Pro-Mist, whose black particles are crystals with facets that scatter more light and reduce contrast.

“Our Digicon filters are made of very, very tiny black particles whose effect is to reduce highlights while increasing black levels. The midtones are not affected. This can add up to two stops of latitude to a typical HD camera, compressing highlights and lifting shadows to protect detail at exposure extremes. An example of how this filter works entails watching a waveform monitor as the filter is inserted in the matte box: the highlights come down 10 ire and the shadows come up 10 ire. The color rendition is completely neutral.”

On page 3: diffusion in front of the lens or behind the computer?

FIX IT IN POST?

Both Zupka and Tiffen are in agreement that there’s no true replacement for using a filter in front of the lens.

“If you’re doing it up front, in the camera, you’re affecting the image in a 14-bit color space,” says Zupka, referring to the color depth at which many HD imagers capture data. “On tape you’re down to 10-bit, or 8-bit. The higher the bit depth, the larger the palette of colors to choose from. Also, any time you manipulate the red, green or blue gains in a camera to create a look you’re susceptible to adding noise from pushing a color channel too far.

“Also, filters like polarizers and diffusion interact with the lighting and texture of the object you’re shooting. You can’t recreate that in post.”

“I like to quote Hank Harrison,” says Tiffen. “He said, ‘When you put a filter on a camera you are dealing with an infinite number of luminance levels and variety. You lose that once you go to any recording medium. It’s ALWAYS different when you try to affect a recording instead of the real thing. There’s nothing that replaces the real world as a source of information.'”

Having said that, Tiffen was a major proponent of the software package that is now known as Tiffen DFX. “Post filtering is an increasingly valuable tool for arriving at the look we want. As with everything else–lighting, gels, cameras, lenses, set design, and costumes, to name a few–there are many variables that offer control points. Post filtering is another relatively new addition to the arsenal of effects. The idea is to use the camera, with its digital and optical capabilities, to get as close to the end result as is reasonable. Then post options can be used to bring the final image to successful fruition.”

When I suggested that Tiffen DFX effects were similar to, but not a match for, the Tiffen filters they claim to emulate, he said that didn’t matter. “There isn’t a practical difference because the people who see the final result aren’t doing comparisons between the actual filter and the emulation. As long as you’re consistently using one or the other, there is no need for concern. It’s all a matter of practical differences and circumstances.”

He offers a word of warning, however. “Fixing it in post is more and more frequent. You have to know that there’s only so much range you can adjust in post, due to the flaws in the recording medium. You’re better off getting it as close as possible in camera if you can. Shooting it clean and fixing it later only works if you know exactly what you can do later.

“Filter use comes down to visualization,” says Tiffen. “If you know what look you want, use the filter that will give it to you.”

On page 4: diffusion in the digital age…

FILTERS AND HD: NOW IT’S ROCKET SCIENCE

There are lot of things that factor into a look, says Zupka. “Lenses have different looks. A Sony camera looks different from a Panasonic, a Genesis or a RED. Apparent depth of field varies based on imager size. Recording formats have their own looks. All of these factor into what effect a filter will yield. Fortunately, for broadcast work we can see the effects immediately on a good monitor.

“For film outputs, a good rule of thumb is to use the filter that looks good on the monitor and then back off a couple of strengths. This is no replacement for testing in advance, but it can work.”

“There are no more variables in HD than there were in film,” says Tiffen. “The difference is they change more often. Otherwise they interact in the same way that things have in the past. The fact that film stocks were relatively stable meant you could take the time to get familiar with them. Not so much today.

“The caveat always is, when possible, test: if you have an understanding of the basics, filters won’t be as daunting. If you want flare, and a variety of filters offer flare, then you can guesstimate which one you want–but you can only confirm with tests.”

“It’s all about predictability,” says Zupka. “Once you know what a filter will do, it will always do it the same way: scatter light the same way, lower resolution the same way, lower contrast the same way–it’s always predictable.”

When I asked if they minded participating in an article together, neither Zupka nor Tiffen objected. They both know each other from way back. “The nice thing about the filter industry is that we rarely try to copy each other,” says Zupka. “There’s no point. We’re all better off trying to develop completely new products.”

On page 5: about the interviewees…

ABOUT THE INTERVIEWEES

Ira Tiffen was literally born into the industry in 1951. His father and two uncles owned a thriving business that made photographic accessories. “Dad started at 17 as an airplane mechanic,” says Tiffen, “and by 19 he was foreman of a machine shop. At 21 he owned his own machine shop and started making lens caps, lens shades, adapter rings and other camera accessories, including filter rings. At the request of his customers he sourced filter glass from then available vendors to supply complete filters. Soon after, though, he realized that this glass was not up to his customers’ requirements, so he began the development of of what became his unique method of laminating filter glass.”

Tiffen watched his father formalize the FLB and FLD camera filters under flourescent lights in the family basement, and when he was old enough he came to work summers at the family business. He graduated from NYU with a degree in Chemical Engineering and started work full-time shortly thereafter. He left Tiffen, Inc. to pursue his own interests in May, 2004.

Bob Zupka spent 12 years in the reconnaissance industry building high-altitude surveillance systems, and remembers when the industry went from film capture to high definition imaging in 1985. “A lot of the same issues came up then that we are dealing with today,” he says. “Which one is easier to manipulate, things that you can and can’t do with each one, etc.”

In 1996 Zulpka took a job at Schneider Optics, a company with a thriving business in manufacturing projection lenses for screening rooms, but that had also been making still photography lenses and filters since 1913. Schneider wanted to break into the film industry, but the German-based company wasn’t set up to build the large filters required for film work. Zulpka started a U.S. factory from scratch to built 6×6 and 5×5 filters.

Art Adams is a DP who no longer confuses diffusion when he uses it in profusion. His web site is at www.artadams.net.