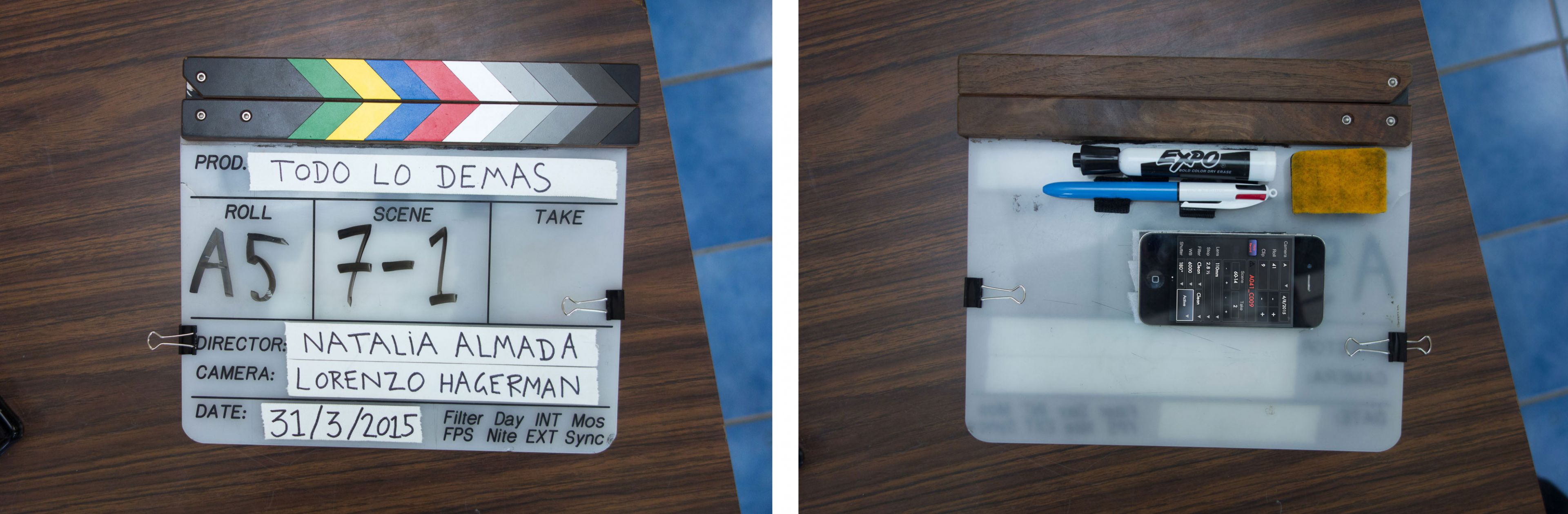

Dave Cerf’s accomplishments are varied and vast. To name a few: He has composed music for Sam Green’s Academy Award nominated The Weather Underground. He has written manuals for legacy versions of Final Cut Pro. He assisted editor Walter Murch on two feature films, Hemingway and Gellhorn (HBO) and Brad Bird’s Tomorrowland (Disney), and he volunteered at the Dalai Lama’s video archive in India. He recently completed scoring, editing, and post-production for Mexican filmmaker Natalia Almada’s award-winning fourth feature film, Todo Lo Demás, starring Academy Award nominee Adriana Barraza.

In my interview with Dave, I was impressed by the depth of his experience. Dave talks about his creative process—rhythms of sounds and music, experimenting with picture edits, and sonic choices—right alongside technical aspects, such as Python scripts, Filemaker Pro databases, and the power and possibilities of XML.

“Final Cut Pro X allows for a great deal of mastery thanks to a deep feature set and a responsive user interface.” – Dave Cerf, Editor

MM: Did the director have input on how the editing was done? Did she care?

DC: Technically speaking, not much. Natalia edited her previous three documentaries using Final Cut Pro “Classic,” but the scale of this project required a more modern NLE. Premiere Pro was considered briefly, but the imminent release of Focus made Final Cut Pro X a viable option (thanks Mike!). Simplemente (who also provided the RED camera and Quantum storage) and FCPWorks consulted with us and connected any workflow dots we were concerned about.

Like many people, Natalia experienced the infamous 1–2-week Final Cut Pro X adjustment period, but after that it was pretty smooth sailing.

MM: How did Natalia’s documentary experience relate in Final Cut Pro X? In what ways did she adopt that workflow? Was there any one thing (or more) in particular that stood out for her as a bonus?

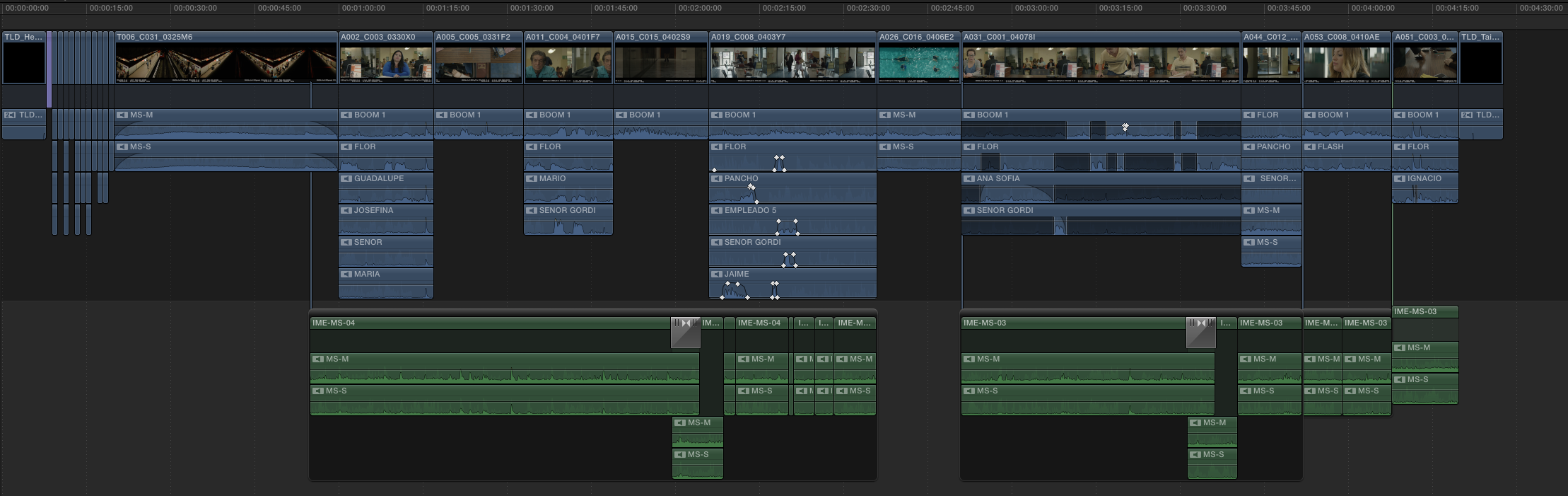

DC: Todo Lo Demás was her first fiction film and at the same time it was our first experience cutting with Final Cut Pro X. If the finished movie was a more conventional fiction adhering closely to the script, I think it would be hard to untangle those two first-time experiences. As it turns out, Todo Lo Demás was edited more like a documentary—shots from one scene were frequently used in a totally different context. And Final Cut Pro X turned out to be fantastic for this.

At first, Natalia was concerned when she saw all those filmstrips everywhere. She said, “Please tell me there is a list view—that’s how I work in Final Cut [7].” She was relieved to see that option existed in Final Cut Pro X, but after a few days, she discovered the freedom of visually skimming the media across the entire library. We used list view rarely, for more organizational tasks like entering notes about a project.

It can be scary to abandon the reassuring orderliness of a list view and replace it with skimming in Final Cut Pro X, which at first makes the interface feel twitchy or overwhelming. But after a while, the more conventional NLE’s start to feel lifeless and unresponsive in comparison. Viewing a clip in those environments is like going over a speed bump—a brief deceleration as you double-click to open the clip and then you’re back on your way. Then you want to open another clip and—bump—it’s open. Final Cut Pro X comes along and essentially grinds those speed bumps down to nothing, leaving the road clear for acceleration.

But it’s not speed for its own sake that makes this frictionless navigation so wonderful—it’s the fact that you’re spending more time immersed in the media’s native visual form. There are less interruptions in the experience of looking and watching, which is how you familiarize yourself with the material. Meanwhile, the ability to dynamically search via keywords (such as location or character) reconfigures the media landscape beneath the skimming line, refreshing and re-contextualizing your source material at will.

Natalia was able to work almost entirely visually and not worry about details like scene numbers. This would be untenable in other NLEs. I would say that her documentary process actually flourished in a way it had not been able to before, and yet we were not even making a documentary!

MM: How does the ability to search via keywords and other metadata effect conventional project organization (like bins)?

DC: I still recommend having a baseline organizational method—one event per production day for fiction, one event per location or character and/or per shoot day for documentary. You still need an experienced editor or assistant with the skills to make that happen.

MM: So you’re saying Final Cut Pro X does not magically solve organizational problems?

DC: If you make some effort adding metadata and keywords, and add to that automatic role assignment via production sound iXML, then actually, Final Cut Pro X does have a magical organizational quality. It’s not so much that it eliminates the task of organization; rather, you are not limited to the baseline organization you started with. We initially organized our events by shooting day, but I don’t think we ever viewed the clips that way. Instead, we would organize by scene, character, time of day, location, or even combinations of all those. You can also adjust your organizational strategy as you go, adding new keywords as you become more familiar with the material.

The creative process is inherently messy, which is often in direct conflict with the housekeeping a technical collaboration like filmmaking requires. Apple has acknowledged the dual need for freeform experimentation and order in a way I haven’t seen elsewhere… and not just in the Browser. Having clips move out of your way while you trim in the Timeline is kind of messy by conventional editing standards. Traditionally, you want to control the track where each clip goes. But then they provide roles so you can let go of some of those concerns mid-trim—the moment you care least about organization.

For all this to work, you have to learn to trust the metadata, and that takes time and experience. Everyone on the team, starting all the way in pre-production, should commit to an effective metadata workflow.

“Final Cut Pro X freed up time for creative work because the software is so effective at searching and skimming media.” – Dave Cerf, Editor

MM: Can you share something from your personal creative process in respect to how Final Cut Pro X benefits you?

For me, editing is comparable to musical performance and the software is the editor’s instrument. The degree of mastery that an instrument allows determines how far a motivated performer can go (consider the piano’s range of possibilities, from Twinkle Twinkle Little Star to Chopin’s virtuosity).

I think Final Cut Pro X allows for a great deal of mastery thanks to a deep feature set and a responsive user interface. For example, you may start out editing with the Blade Tool, then get faster when you discover Command-B, then faster still using commands like Trim Start and End. There is also the ability to edit during playback. This is common in DAW software like Pro Tools, but unusual for a video NLE’s. You may not use this right away—you may even find it overwhelming at first—but once you have a certain “temporal fluency” it’s possible to watch/listen to one part of the timeline while adjusting another.

When I have an editorial idea (“let’s rearrange the order of these shots”), I have to translate that into a sequence of editorial actions and then perform those as quickly as possible before I (or the director) loses patience. Musically speaking, it’s like hearing a melody in your head and wanting to know how it sounds out loud. With Final Cut Pro X, you can learn to express that melody almost as quickly as you’re conceiving it. Maybe you won’t be that facile your first week, but eventually…

The ease of learning Twinkle Twinkle Little Star on the piano didn’t preclude Chopin’s blazing arpeggios, and so it seems to be with Final Cut Pro X.

MM: Are there any scenes that evolved beyond the original script during the editing process?

Before the screenplay, Natalia wrote prose imagining her character’s thoughts while lying in bed at night listening to the sounds of the city. There was a passage where Flor, the main character, hears a neighbor playing piano while a street light outside her window slowly pulses on and off. There is also the rhythm of her breath as she lets go of the day and drifts to sleep. She craves an alignment between all these disparate meters just as she desires integration of old, unresolved feelings into her present life.

When the prose was converted to the screenplay, a lot of those details were lost. Re-reading the original passage, I was reminded of that phenomenon in the car where the turn signal clicks in and out of sync with the blinker of the car ahead. Watching them go in and out of phase can be hypnotic.

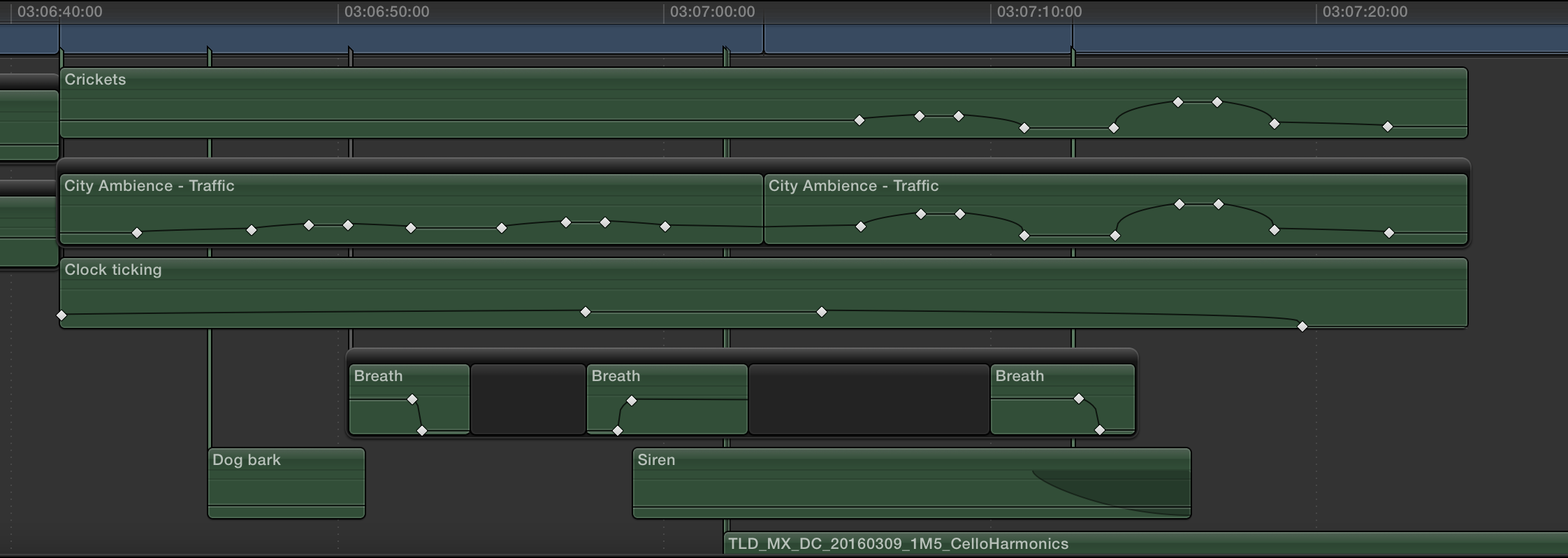

We had a shot of Flor lying in bed with a light from the window gently fading up and down, her face coming in and out of darkness. To build the scene, I started out making some piano music in Logic Pro X, processed as if coming from another room. But no matter how hard we tried to make piano seem like a sound in the environment, it suggested a musical score rather than a person practicing in the other room. The point of the scene was rhythm but the harmonic content was distracting. So, the piano, the primary sonic element in the script, had to go, leaving us with only ambient sound. We added a ticking clock which contrasted with the pulsing light and provided some of the out-of-phase “turn signal effect” I mentioned previously, but we still needed to find a way to get those elements to eventually drift into alignment.

One technique I picked up from Walter [Murch] is to edit scenes silently before adding any sound at all. For this scene, I tried the exact opposite, sketching it out with only sound and no picture. I started with ambient sounds of the city and the ticking clock, but without an image we had lost Flor’s presence in the scene, so I added some very subtle breathing sounds. It seems obvious in retrospect, but I don’t think it would have occurred to me to add that sound if I was working with the picture, because Flor was already there in the image. In the sound-only sketch, she didn’t exist until we added the breathing.

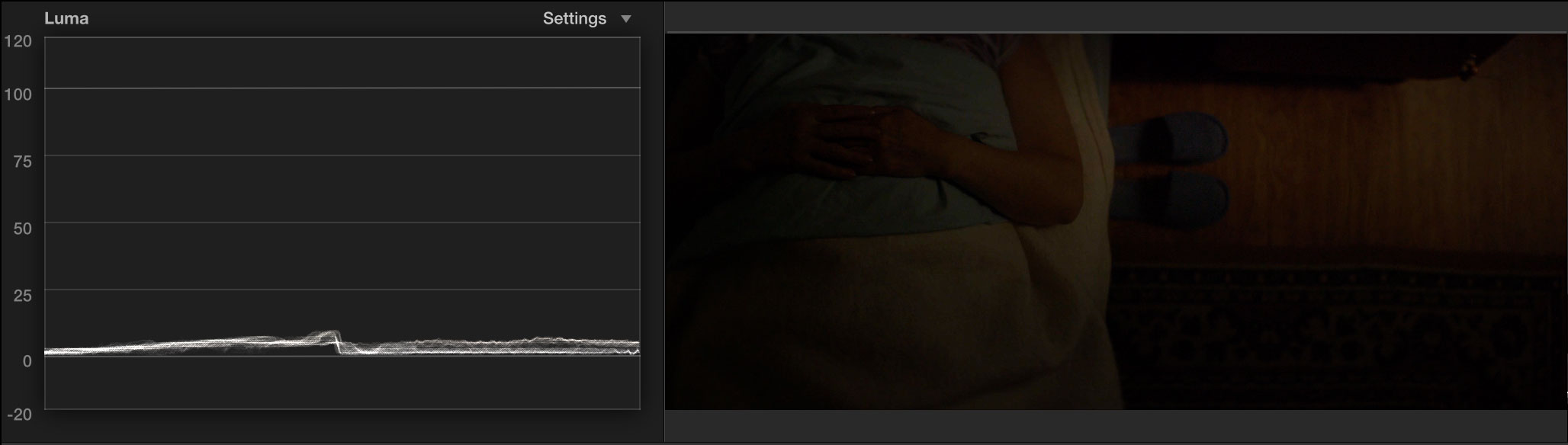

When I turned the picture back on, I noticed the waveform monitor trace was moving up in down in time with the pulsing light in the scene; it seemed like a medical device measuring someone’s breathing rate. Now we had two breathing elements—the light and Flor. I wondered if we could somehow control the volume of an audio clip directly from the waveform monitor. In other words, maybe we could give the light its own sound.

I tried the Tremolo effect in Logic Pro X (conveniently also available in Final Cut Pro X), which varies the volume of a clip at regular intervals. But to appreciate the effect you really need a continuous sound, like white noise, or the ocean, or… the ambient sound of the city.

Finally, we had the ingredients to express this convergence of disparate elements in both the picture and sound. The clock would establish one rhythm and the light another. Over the course of the scene, the pulsing of the ambient sound would get more pronounced, moving from an unconscious background sound to the focus of the scene. We eventually replaced the Tremolo effect with volume keyframes using the waveform as our guide.

We referred to the effect as “light breathing,” and the work in Final Cut Pro X served as a template for more nuanced automation in Pro Tools. In the final mix, to me, if feels as though the film itself is breathing. I really love it when the sound design can take on the typical role of music.

MM: How much did you integrate with Logic Pro X?

DC: I don’t think it would be fair to call what we did “integration,” but I did use Logic Pro X a fair amount, such as when creating the sound-only sketches I mentioned before. Whenever the sound design called for a more musical element, such as piano, it was really convenient to open up Logic, record, bounce, and import back into Final Cut Pro X.

Sometimes I’d create something in Logic where simply importing the audio mixdown into Final Cut Pro X wasn’t enough, like when we’d want to customize some effects settings in relation to the picture. Because both applications use the same Audio Units, it was easy to recreate segments from Logic in Final Cut Pro X.

I also used Logic Pro X to compose the music and generate sheet music and MIDI files for the musicians in New York.

I think Logic has been one of the best acquisition stories in Apple’s software division. The latest version feels like a completely modern piece of software despite its origins going back all the way to the ’90s. I would love deeper native integration between Final Cut Pro and Logic, but at the same time I think the Final Cut Pro team has been doing such a good job with audio editing features that it doesn’t feel as imperative as it once did.

MM: As the post-supervisor and producer, specifically where did Final Cut Pro X save you time and/or money? And how did you approach the film and the production from those different perspectives?

DC: Final Cut Pro X freed up time for creative work because the software is so effective at searching and skimming media. We also saved a fair amount of money by keeping certain tasks in-house. We did a lot of pre-conforming in Resolve and Pro Tools before handing off in order to ensure we caught errors before they became expensive issues at the various finishing facilities.

There was also the flexibility to develop the specific tools we needed for our workflow. Again, this might take more time, but it saved us money, and we did not have to negotiate with developers whose schedules might not have prioritized our project’s needs.

As an editor, I could not make any excuses that the workflow was getting in the way because I was the one developing the workflow as post-production supervisor. As post-production supervisor, my workflow had to accommodate my creative needs as editor.

I think inhabiting both roles forced me to find a healthy separation between creative and technical concerns. For example, while editing, I sometimes had an idea and then I would hear the post-production supervisor voice chime in: “Don’t make those changes. Think how it will impact the VFX turnover next week.” I would remind myself that I could think about the technical concerns later, but in the moment I simply needed to edit.

“You have to learn to trust the metadata, and that takes time and experience. Everyone on the team, starting all the way in pre-production, should commit to an effective metadata workflow.” – Dave Cerf, Editor

MM: You worked in three countries across two continents. Did editing come along? If so, can you talk about your portability?

DC: Our goal for mobility was simple: To be able to edit anywhere with minimum setup hassle.

Our home-base moved between Mexico City, San Francisco, and the Marin Headlands; those systems were not particularly portable (a Mac Pro, two displays, and stereo speakers). Natalia also worked on the film at several art residencies where she used a MacBook Pro, an additional calibrated display and headphones. (As a side note: I think the Final Cut Pro X 10.3 refreshed interface will make editing on smaller screens easier.)

We chose a ProRes 422 dailies workflow (1920 x 1080, 4 TB total) over using raw RED files (3792 x 3160, 20+ TB total), which was the biggest factor in terms of portability. We had three copies of the ProRes dailies files—two in the current edit location (e.g., San Francisco) and one at another home base (e.g., Mexico). Our dailies workflow was robust enough that even if we’d lost all the ProRes files we could easily regenerate them from the raw files, so three copies was sufficient.

For the most part, editing was done serially (meaning only one person was updating the movie timeline at a time). In the cases where we were editing in different locations simultaneously, we would split the Library into two copies which would diverge over time, and then manually merge them together when we were physically reunited.

MM: How did that part of the process go? Adding one editor’s cuts to another’s Library?

DC: Really smoothly—just an occasional relink when a voiceover file (for ADR) was recorded into the Library package and not sent along with the transfer Library. We made sure all of our dailies hard drives had the same name (“TLD_Edit”) so Final Cut Pro X wouldn’t have to worry about relinking to a drive with a new name.

MM: You were deeply integrated with FileMaker Pro. Can you talk a bit about that process along with how Sync-N-Link X and your custom-built Python scripts served you?

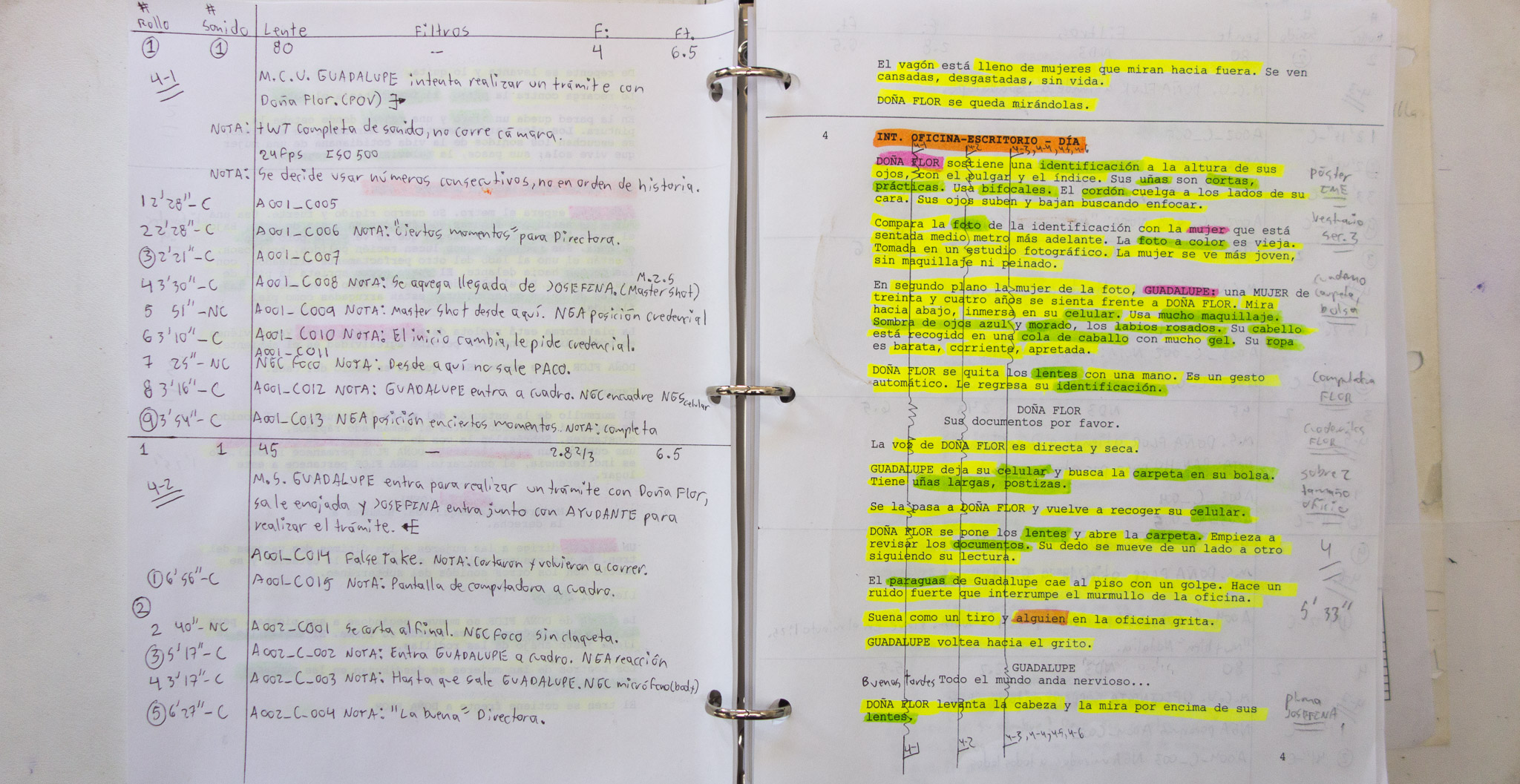

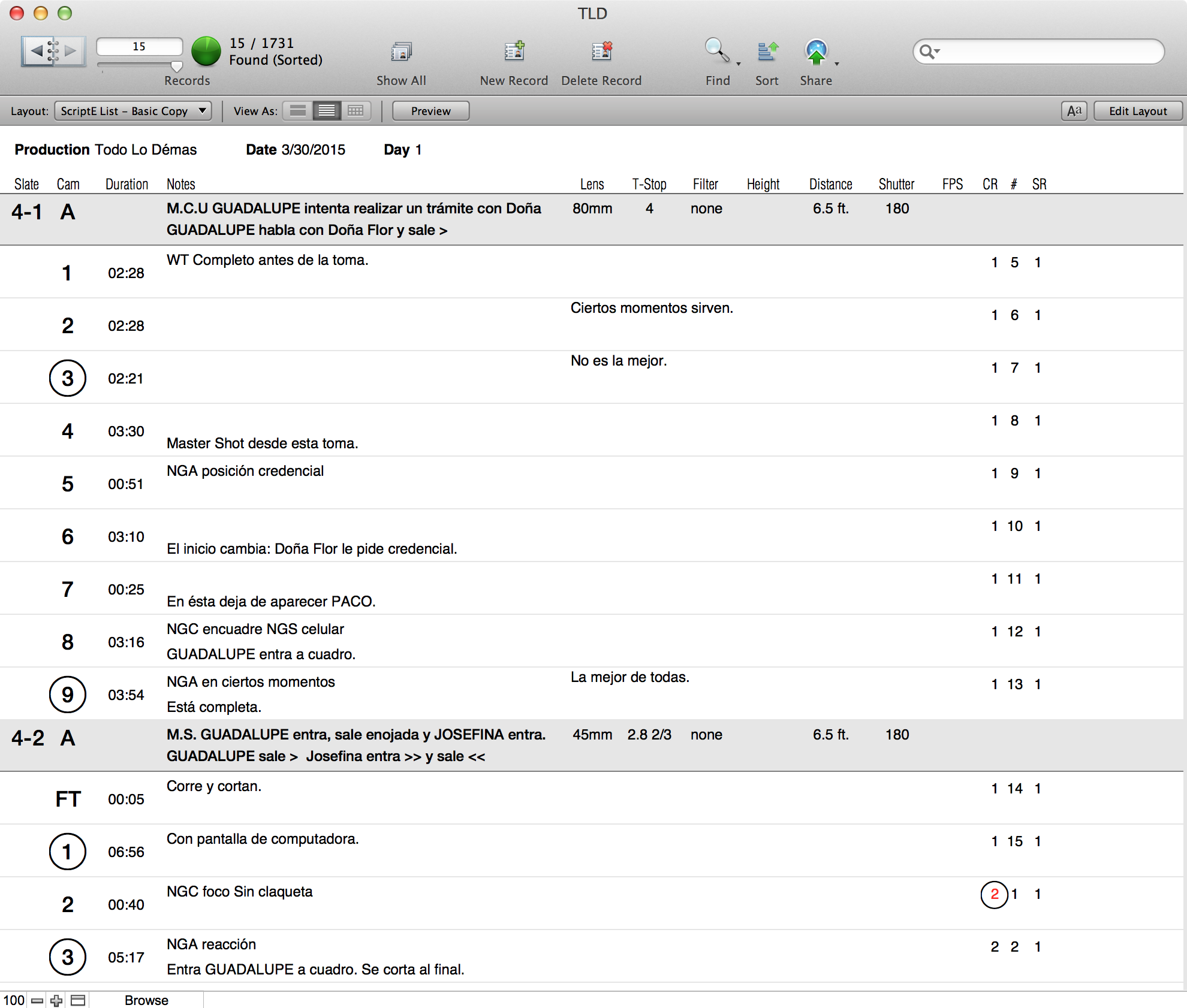

DC: Our FileMaker database was an evolutionary offshoot of Walter Murch’s Log Book, which he has been developing for several decades. I got to know the Log Book quite intimately in the last five years, so anyone familiar with it would feel its spirit in the Todo Lo Demás database, even though it was created from scratch.

We put a lot of things into FileMaker and then tried to push as much of that via XML into Final Cut Pro X. FileMaker is really good at correlating the data, but it’s obviously more convenient to have that information directly in your NLE. And in Final Cut Pro X 10.3, all that metadata is now searchable, so you can find things based on script supervisor notes, camera report data like lens type, etc.

Python scripts (in an AppleScript wrapper for drag and drop support) were used to format or extract media metadata into a FileMaker-friendly tabular format. XSL templates (FileMaker’s preferred method for transforming XML data) were used for importing XML file formats.

Python was also used to extract, alter, or merge data in FCPXML events. To keep our tools portable across systems, I limited the underlying software libraries to ones included with OS X.

Here are some examples of what we imported into FileMaker:

- The screenplay (since Final Draft now uses an XML format), including a list of scenes, locations, and page counts

- all the production metadata—both human- and machine-generated. Each kind of report (camera report, sound report, script notes) had its own table, as well as tables for R3D, RMD, and Broadcast WAVE metadata.

- Still images marked in REDCINE-X PRO while dailies were processed

- File paths for all raw (R3D, WAVE) and dailies (ProRes)

Having this information in one application was useful, but where FileMaker really shines is its ability to relate data fields across tables. For example, if the camera report, script notes, and R3D metadata all contain the same shot name (A019_C008_0403Y7), you can see all the information about that shot, across departments and devices, in one unified view.

This also helps catch errors, such as misnamed shots or when camera/script reports mistakenly described two shots when in fact there was only one (because the camera hadn’t stopped after “cut” was called). We called this error correction step “Conflict Resolution.” I’ve used it on three films now, though this is the first time I was able to dictate when it happens, which is ideally before dailies are generated. Fixing metadata early on prevents errors from multiplying downstream in editorial, sound, and color.

Dailies were generated programmatically using a Python script which triggered redline (RED’s command line version of REDCINE-X PRO). The script pulled in metadata from FileMaker Pro to create metadata-rich burn-ins, including things like the names of each audio channel (the audio folks downstream found it helpful to know what audio might be available for a shot just by looking at the burn-in).

In terms of integrating the FileMaker database with our Final Cut Pro library, we did something like Shot Notes X, but in a more comprehensive (albeit less user-friendly) manner. We took all the cross-referenced metadata in FileMaker Pro and pushed it into our Final Cut Pro X library. Here are the introductory comments in the Python script that handled that task:

This script takes the following two inputs:

-

a merge (.mer) file (basically a CSV with a header row containing column names) exported from a FileMaker Pro database of clips

-

an FCPXML event

The script cycles through each clip in the CSV file, searches for that clip’s name in the FCPXML, and adds keywords, keyword collections and metadata to it.

We ended up with a number of custom metadata fields (all with the prefix TLD) that were visible in the Inspector. In Final Cut Pro X 10.3, all that metadata is searchable. I still wish there was a way to display that metadata as an onscreen overlay in the Viewer, since the burn-ins don’t always tell the full story.

MM: Did camera and sound work with electronic script supervision/reporting?

DC: Good question. We built a FileMaker Go database for the camera reports. The script supervisor was a straight-up pencil-and-paper fellow. He entered his data into Excel at the end of each production day, and I would import that into FileMaker.

MM: Seems like a lot of extra work because of the double entry. Would you lobby for some electronic adaptation in the future? Smart slates?

DC: I think digitizing the script supervisor process could make things more efficient, but I have changed my tune from “digital at any cost” to whatever system allows each team member to work most effectively. Asking Néstor, our script supervisor, to work directly in Excel or FileMaker on set (which I did at the beginning) would have slowed him down. In this case, having him do double entry was the most effective solution even though it took more time and effort. Across disciplines (not just in filmmaking), paper-and-pencil tools offer a few things digital systems still cannot compete with—cheapness, robustness of materials, and no format limitations (you can write anywhere on a piece of paper without having to find the right database field to enter information).

Paper-and-pencil is not easily replaced, but any steps made toward augmenting those tools with digital solutions would likely be adopted beyond merely filmmaking.

In my fantasy film production, there would always be a developer on hand, one who is equally capable in interface design and robust engineering. That person would visit set and editorial regularly, observing the challenges on both sides, and develop prototype solutions that we would fold into the actual workflow.

In an even more fantastical scenario, a new wave of more accessible programming tools allows editors and production crew to create the workflows they need without dependence on programmers.

MM: Any thoughts on programs like ScriptE or other electronic script supervisor software?

DC: For supervisors who are comfortable with them, I think digital tools like ScriptE are a win-win for both the supervisors and editorial. I have not seen ScriptE’s XML output lately—it may be radically different now—but I worked with them circa 2011 to come up with a set of fields to export for our production which worked seamlessly.

However, I’m not really worried about the supervisors who have already adopted digital tools. It is the ones who find the digital tools lacking that I believe we need to listen to very carefully. It isn’t always fear of change that causes someone to resist the new tools; sometimes the new tools are just less effective.

MM: Can you talk about your process for your credit roll?

Our credit roll was created in-house using Illustrator and After Effects, but the lead-up workflow was kind of interesting. We found that people on the team had a hard time “seeing” the proposed credit list when sent in plain text of a spreadsheet, so we developed a way to create online credit rolls in HTML, authored in a simple markup language. All you had to do was send people a URL and they would see the animated roll, formatted to like the real thing. Check out http://davecerf.com/scrolldown/. (Refresh the browser once when looking at the sample pages.)

“Seeing the character names on each production audio track was really helpful during editorial, and having those names map to Pro Tools tracks is also fantastic.” – Dave Cerf, Editor

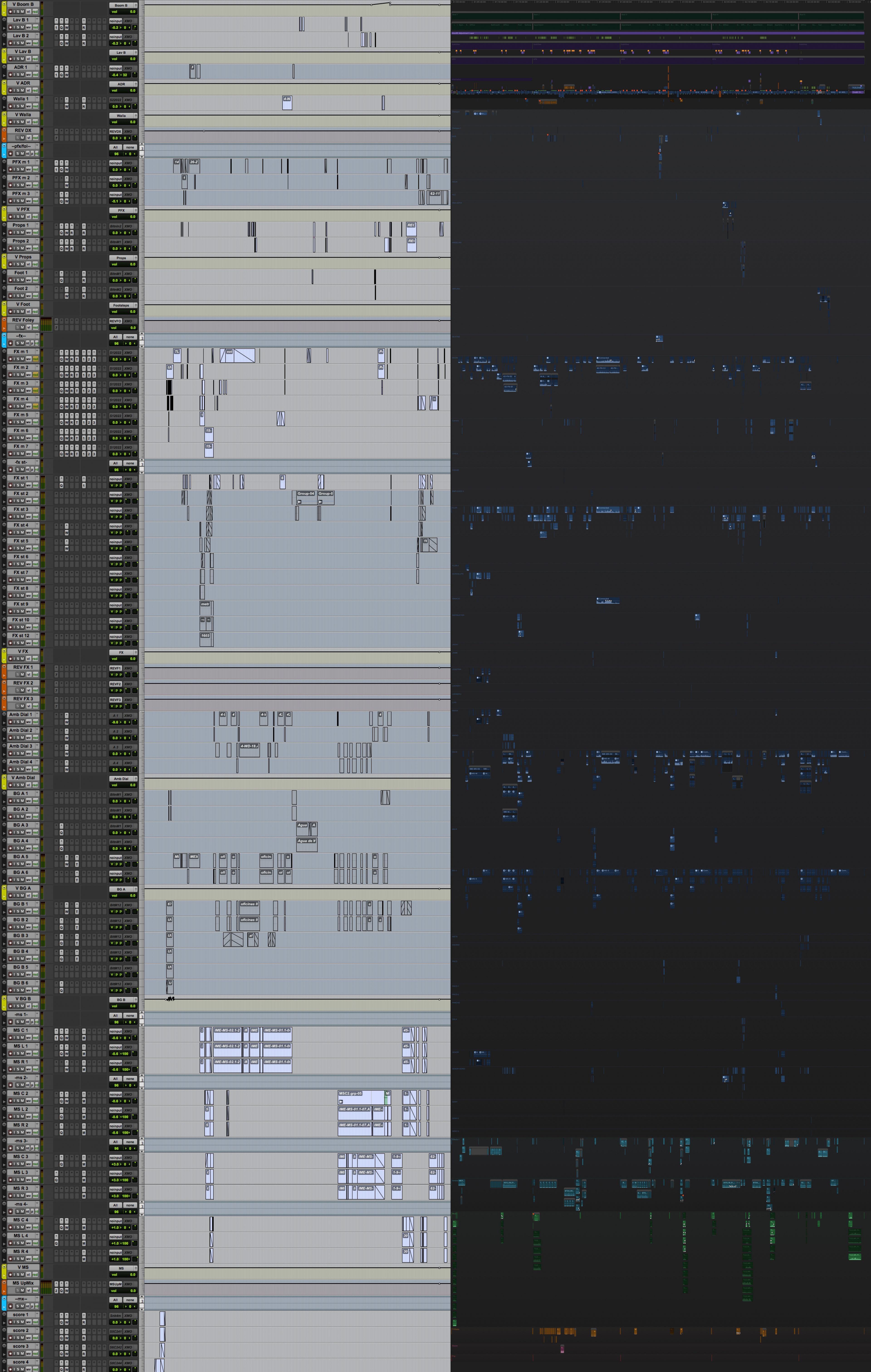

MM: Please talk about your use of Roles.

We had just a few roles: Dialogue, Music, Effects, TV/Radio, and Master (used towards the end when we pulled Pro Tools mixes into our projects). There were nearly fifty Dialogue subroles for the various characters in the movie, all generated automatically via Sync-N-Link X.

I like to do a lot of sound design while editing, so vertical management of the audio clips definitely got tricky, especially for Natalia who was more focused on picture but had to contend with all the audio I had added. If we had been using Final Cut Pro X 10.3 (we were using version 10.2), it would have been a non-issue.

Obviously, the absence of tracks is one of the most criticized feature of Final Cut Pro X. I’ll throw in my two cents here: yes, there is something reassuring about tracks… until you don’t have enough of them and need just one more… or you get too many of them and they become a navigational headache. Picking a strict template at the beginning of the project (“Four tracks for dialogue—that’s how it’s going to be”) can cause unnecessary tension between editors and their assistants. Editors are focused on developing the best tasting dish, regardless of how messy the kitchen gets. Assistants want to keep things tidy at all times in case they’re asked for an impromptu handoff to the sound department.

Final Cut Pro X solves this by helping you make vertical space for clips as needed, automatically, in mid-trim. I find this so remarkable and satisfying every time it happens. Role assignment keeps the assistant editor calm (whether a real person or just an anxious voice in your head) because roles will map to tracks downstream (in Pro Tools, most likely). In other words, the cleanup process is automatic as long as you properly assign roles in advance. And in version 10.3, you can even get a track-like view of your timeline, which looks pretty similar to the layout you’ll eventually see in Pro Tools.

MM: Audio work was done at Skywalker and Arte Sonico. How was the Final Cut Pro X pipeline received in the sound world?

DC: First of all, we are so grateful for the opportunity to mix with Lora Hirschberg at Skywalker. Everyone there cares so deeply about their craft and they have the resources to do things well.

We used X2Pro to generate an AAF of each reel and then converted those to Pro Tools sessions which we handed off to our sound designer, Alejandro de Icaza, at Arte Sonico. This was more effort on our [editorial’s] part, but I wanted to make sure the session was well-organized for the handoff and that the clips on the timeline survived the conversion.

We only worked at Skywalker for a few days, for the final mix. Since they received Pro Tools sessions from Arte Sonico, they didn’t feel the impact of our choice to use Final Cut Pro X. That said, having been through the process once, I’d feel confident working directly with Skywalker on a project edited in Final Cut Pro X.

The roles-based approach yields something different from the typical 8–24 track AAF (or OMF) audio facilities are used to receiving from other NLEs. Even with the best intentions, anything unconventional can initially upset established pipelines. It will take time to realize the X2Pro workflow can actually remove tedious steps, like providing named tracks and including all the production audio in the timeline (instead of the typical workflow where editorial works only with production’s mix track and the sound department is responsible for lining up the other production tracks).

The one thing I’d do differently is convert our polyphonic production audio files to monophonic before doing dailies. The polyphonic audio worked fine in Final Cut Pro X, but Pro Tools couldn’t relink the AAF to those files. Being able to relink directly to our production media in Pro Tools would have allowed us to generate edit-only AAF files (i.e. just the clip information without any media), allowing us to send changes to Arte Sonico over email instead of hefty uploads weighing hundreds of megabytes. This might have been a deal breaker for a project with more frequent handoffs, but then, we probably would have tested that more thoroughly.

I think Raul Locatelli, the production recordist, was impacted more than anyone else because we requested that he name the tracks on set (i.e. the iXML metadata workflow). He was a one-man operation (also handling the boom), so he did not want to waste energy entering metadata if we were not going to use it. A lot of productions in Mexico still use Final Cut Pro 7, and the metadata rarely survives to the final stages of post-production. I showed him our workflow with Sync-N-Link X and Final Cut Pro X roles, and that motivated him to do the data entry. Seeing the character names on each production audio track was really helpful during editorial, and having those names map to Pro Tools tracks is also fantastic.

I think one reason metadata workflows have been adopted so slowly, despite the potential advantages, is that the person doing the data entry has to see the benefit in the extra work, if not benefit directly. Negotiating the metadata workflow, whether it’s with the sound crew or the script supervisor or camera department, is a two-way street. For example, if Pro Tools operators never use painstakingly entered metadata, production recordists will stop making the effort to record it, which guarantees Pro Tools operator won’t see it, ad infinitum.

“Natalia was able to work almost entirely visually and not worry about scene numbers. This would be untenable in other NLEs.” – Dave Cerf, Editor

MM: What are a few advantages over Avid that come with Final Cut Pro X in your opinion?

DC: I think my reasons for liking Final Cut Pro X, Final Cut Pro 7, and even Premiere over Avid may be somewhat obscure: the ability to extend the software beyond its intended design via scripting, XML, and so forth. Final Cut Pro X lacks scripting support, but it is amazing what you can do with a human readable format like FCPXML (compared to, say, AAF, which is impenetrable to all but the most dedicated engineers).

I prefer open media management where you can import just about any format and try something out editorially right away. Avid media management diehards will correctly argue that this flexibility poses risks down the line; it seems that whole debate comes down to personal style: a rigid black box solution versus something flexible enough to shoot your own foot off.

Final Cut Pro X does a really good job with audio editing: fade handles are a real pleasure, and I love the ability to edit at subframe resolutions without needing any special knowledge—it just works. (Have you ever seen what happens between Media Composer and Pro Tools because of limitations on the Media Composer side?)

MM: I have! If you had to pick three things that made your job better because of Final Cut Pro X, what would they be?

DC: First, searching in the browser and the timeline index. The film was shot in a somewhat modular fashion, so we were constantly pulling shots from one scene and using them elsewhere.

(I actually made an animation recently that shows the distribution of shots, based on their original scene assignment, throughout the movie.)

MM: I like to work with “section” names. I will keyword three or four sequential scenes, “the motel fire” or something like that, rather than working with scene numbers. I think the numbers are irrelevant after filming until editing stops.

DC: It is interesting to hear you say that. We did something similar. The movie takes place over the course of several days (in screenplay time), so each scene, and thus each shot, belonged to a “supercategory” called Day. For example, we could search for all the shots where the actress was wearing a particular outfit by searching for shots assigned to Day 3 of the script. This was distinct from Shooting Day 3 (production time), which we could also search for.

MM: Okay. What’s the second thing that made life easier?

DC: Split edits and audio components. I never get tired of that magic feeling when opening up and extending a clip’s audio components while other audio clips in the timeline move out of the way. This expand/collapse gesture has become so intuitive to me that I miss it when I go back to other NLEs.

We did notice that collapsed split edits, especially when they are quite long, can cause a lot of confusion (you hear a sound but can’t figure out which audio clip it’s coming from because it’s actually hidden in the collapsed split). I imagine this could be solved in a few ways in the interface.

MM: And number three?

DC: Playback never stops. I’m not sure how many people think about this, but Final Cut Pro X does a pretty amazing job playing back even while you are editing. This is something I have always enjoyed in Pro Tools—it feels like the system can really keep up with you as your mastery of the software improves. It is really hard for me now to work with an NLE that has to stop playback all the time. Just being able to keep playback going while I switch to another application still feels magical compared to working in Final Cut Pro 7.

I want to add a fourth point, because three was not enough.

MM: Great, what’s number four?

DC: I’ve talked about the ways we used XML on this project, but there’s a larger principle here. If Apple genuinely did not care about professional workflows, it never would have included FCPXML. APIs and interchange formats are an acknowledgment from the developer that they cannot anticipate (or keep up with) all of the needs or features. Even if you never use FCPXML directly, you can benefit from using software that supports interchange formats.

There are a few idiosyncrasies to learn, but the XML learning curve pales in comparison to the AAF standard. Back in the Final Cut Pro 4 days, Apple could have chosen AAF as its interchange format, but fortunately they did not. They probably found it too difficult to maintain AAF support and created xmeml (Final Cut Pro “classic” XML) instead. Obviously, it really took off, so much so that Premiere Pro—a competitor—relies on it as a primary interchange format (they’re even starting to customize it for their own purposes). It is hard to make a flexible, robust interchange format, and Apple has done it twice now, first with xmeml, and now with FCPXML. This is the thing I miss most whenever I am working on an Avid project.

The level of creativity and technical prowess by Dave, Natalia and their team has surpassed my own experience and opened my eyes to the power that is available both inside and outside of Final Cut Pro X. Todo Lo Demás was a 6K anamorphic film that met the same technical standards as movies with one hundred times the budget (they spent under one million dollars). This article and the experiences shared should serve as a roadmap for future users who want the creative freedom and technical depth that Final Cut Pro X provides.

The Weather Underground http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0343168/

Walter Murch https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Walter_Murch

Hemingway and Gellhorn http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0423455/

Tomorrowland http://www.imdb.com/title/tt1964418/

Todo lo demás http://www.altamurafilms.com/todolodemas.html

“he volunteered [Dalai Lama]” http://davecerf.com/FourThree/2012/05/

Adriana Barraza https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Adriana_Barraza

Simplemente http://www.simplemente.net

FCPWORKS http://www.fcpworks.com

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now