Last time, we charted early efforts to project TV signals on theater screens. This time, we look at the camera side – electronic acquisition. In the end, digital firsts in BOTH projection and acquisition came down to one movie in a place nowhere near Hollywood. But I’m getting ahead of the story.

In the early days of television there was a lot of experimentation to find a way to make television equipment illuminate a screen with an image comparable to film. As electronic television cameras improved, there were other pioneers who began experimenting with turning an electronic picture into a strip of motion picture film that would be acceptable to theater audiences.

The use of electronic acquisition is an obvious necessity for live programing. For a show to be seen live, it must get to the viewer instantaneously. However, if seeing it live is not practical, such as the three hour time difference between the U.S. East and West coasts, it must be recorded in some way.

Converting electronic television material to 16 or 35mm film was used in the early days of network and syndicated television before videotape was invented. A description of the process at its simplest is a motion picture camera aimed at a television picture tube. The films became known as kinescopes (or kine’s for short) named for the high-resolution picture tube used to produce the video image the film camera recorded.

The optical step required in the conversion from electronic to photographic was responsible for a serious reduction in resolution taking place during the transfer. And kinescopes were expensive due to laboratory services and multiple printing steps. The need for a better medium to deliver television shows across America drove the development of videotape into reality in 1956. Reproduction of the video signal via videotape resulted in a picture that could barely be distinguished from live to the untrained eye.

Here’s a direct comparison of kinescope to videotape on one of the earliest known videotape recordings. “The Edsel Show” was live to Eastern and Central U.S. on October 13, 1957, but recorded on videotape for delayed broadcast to the west coast. Because videotape was so new, a kinescope backup was made and run in sync with the videotape “just in case.” From Kris Trexler – http://kingoftheroad.net/edsel/edselshow1.html

Even with the advent of videotape, magnifying the television signal was still limited by its 525 (NTSC countries) or 625 (PAL countries) interlaced lines. PAL countries fared a little better in that their frame rate was 25 frames per second, only one frame away from film’s standard of 24 frames per second. When projected, the problem of electron beam scan lines and low resolution found in the kinescopes increased dramatically. While motion picture film has grain, it is generally not noticed by the viewer. Video scanning, on the other hand, produced lines that were regular, unmoving and obviously distracting.

Interlacing was also a problem in transferring video to film. Film is inherently a progressive medium – one full frame, 24 times a second. That is, the entire frame of an image is photographed all at once. Not so with analog video. Electron beam scanning takes place from top to bottom on a cathode ray tube (CRT) and cause the phosphors on the face plate (view screen) to glow. The phosphors in early CRT’s were not very efficient. By the time the beam arrived at the bottom of the image, the phosphors at the top were already fading out. As a result, interlacing was introduced.

An interlaced signal’s scanning beam goes from top to bottom in half the time, only reproducing the odd numbered lines. The area at the top of the image doesn’t have time to fade when the beam starts over again reproducing the even numbered lines of the second set of lines containing the other half of the image. These two passes are called fields. The two fields together equal one frame. However, because they are scanned at different times, there is a slight time difference between them. Today, interlacing is still used for broadcast television as it conserves bandwidth.

Before videotape, networks and manufacturers sought other alternatives to the kinescope. The defunct DuMont television network was one of the big three television networks in America along with NBC and CBS (ABC didn’t rise to that status until the early 1950’s). Unfortunately, DuMont had a short lifespan in that it only lasted from 1948 to 1956. However, in the few years it was around, many shows were developed that would later become staples on other networks.

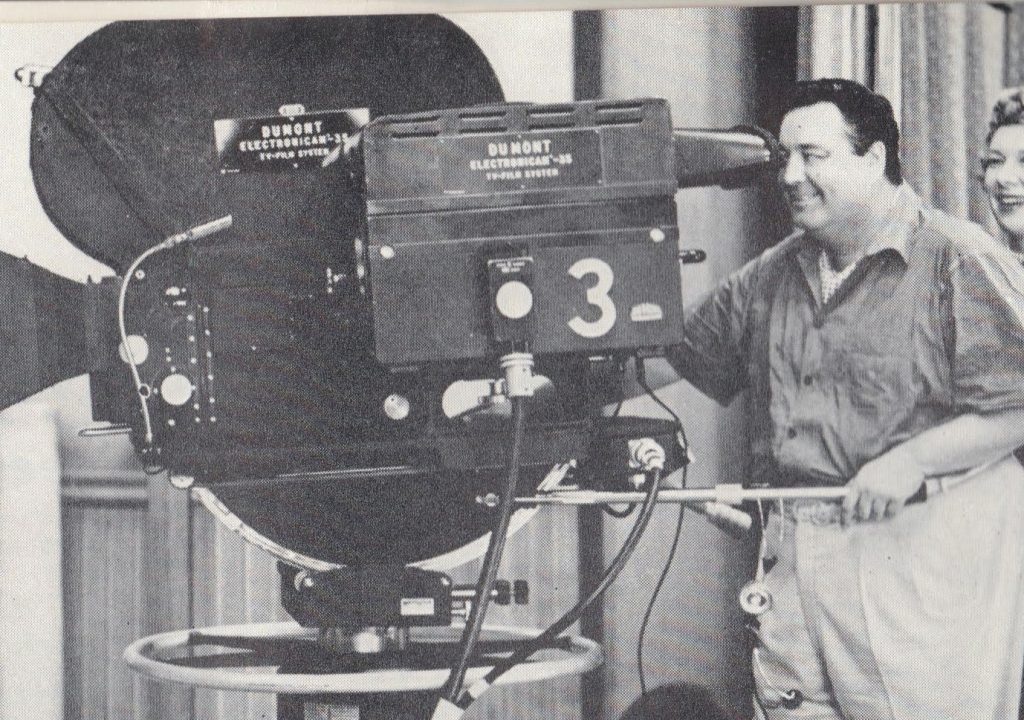

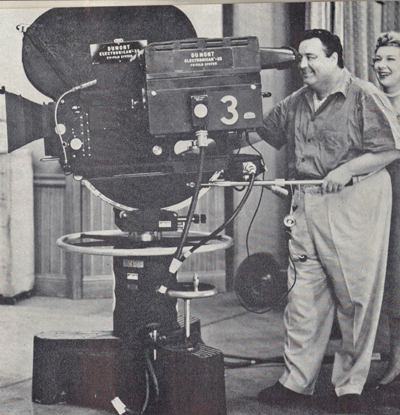

One of DuMont’s programs was the Jackie Gleason classic “The Honeymooners.” To overcome the kinescope quality issue, engineers at DuMont retrofitted several of their live video cameras so they could also shoot 35mm film through the same lens. The image passing through the television lens was split allowing the scene to be captured to both the television pickup tube and the film negative. Dubbed “Electronicam,” four cameras were used during the show’s live telecast with the 35mm mechanism recording the same image the video cameras were transmitting frame for frame. Later, a kinescope recording of the live show was used as a work print to conform each camera negative using standard motion picture editing techniques. The result was a 35mm negative from which high quality prints could be made. The enhanced quality over kinescopes can still be seen in the episodes that continue to run on classic TV channels.

Jackie Gleason operates the DuMont “Electronicam” camera. Gleason frames the shot by looking at the video camera viewfinder while the taking lens is on the front of the film side of the camera.

There doesn’t seem to be any evidence that the Electronicam system was ever used for the production of a film for motion picture distribution. Indeed, the Electronicam system followed the DuMont network when it went into bankruptcy. Years later, as video camera size shrank, similar systems appeared on motion picture cameras and came to be known as “video assist.”

In the mid 1960’s, a self taught engineer named Bill Sargent set out to finally put television on the motion picture screen. He came up with a system he named “Electronovision.” Sargent had made a name for himself in April, 1962, with a live boxing match between Cassius Clay (Mohammad Ali) and George Logan. Some sources call it the premiere of pay per view, but the fight was actually a closed circuit telecast to theaters in 19 cities and had been done before. But beginning in 1964, he produced several theatrical films using RCA TK-60 television cameras and recorded them in such a way they could withstand enlargement of the image to theater screen size. The TK-60 was the latest (and the last) of RCA’s black & white cameras and its imaging system used a new, four and a half inch imaging tube that was sufficiently sensitive to produce low noise pictures in very little light.

The first of the Electronovision productions to be released was a Broadway version of Shakespeare’s “Hamlet” starring Richard Burton. According to an article in the September 1964 American Cinematographer magazine written by Herb Lightman, the video production was made as the cameras were switched live directly to an RCA television film recorder that made a kinescope of the production. But with some enhancements.

In order to avoid the distraction of the scan lines on the projected picture, this early version of Electronovision took advantage of a technique developed by the BBC in 1953. Called the “spot-wobble” process, the distracting scan lines were blurred very slightly until the lines met the one above and below the other. While the blurring slightly reduced resolution, the projected image was free from the artifacts of television’s electron beam scanning.

According to Variety, the film was released to 1000 cinema screens and went on to gross three million dollars. It is still listed as one of the eight best films of Shakespeare’s plays and is available on DVD.

Following the success of “Hamlet,” Sargent applied Electronovision to a music production. This time, full use would be made of the high-resolution capabilities of the four and a half inch Image Orthicon tubes. Since motion picture distribution, not broadcast, was the purpose of the production, it didn’t matter what scanning standard was used. The TK60 cameras were set for the French scanning resolution of 819 lines and a frame rate of 25 frames per second same as the PAL standard. In addition, rather than send the signal directly to a film recorder, 2-inch quadraplex videotape machines were used and also “tweaked” to operate at the French standard.

The “TAMI Show” (for Teenage Music International), is regarded by some as the granddaddy of all rock concert films. It was recorded on October 29th, 1964 at the Santa Monica, California, Civic Auditorium in front of a packed house of screaming teenagers and starred many popular groups in the early days of their careers – The Rolling Stones, The Beachboys, Chuck Berry, James Brown and the Supremes to name a few.

As with “Hamlet,” most of the editing was switched live as the show unfolded. In the days before electronic video editing existed, all edits required the tape be physically cut and rejoined with adhesive tape. Frame accurate edits were very difficult to achieve, if not impossible. So the final cut of the show was cut together from sequences rather than shots. Tape cuts took place when the show could fade to black (i.e., when tape needed to be reloaded or the stage was reset between acts).

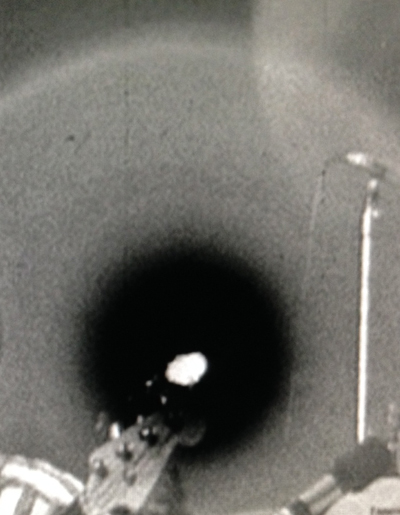

Once again, the video was sent through a television film recorder to make the master negative. With the higher line rate and a frame rate so close to that of film, the footage gained an appearance much closer to a film look in most shots. However, video still gave itself away, particularly in shots where a light came into frame or a shiny object produced a specular highlight. Image orthicon tubes were very sensitive to wide variances of light and extremely bright areas produced black halos.

Example of Image Orthicon “halo” when the tube is exposed to an extremely bright pinpoint of light.

Another Electronovision project followed in 1965. “Harlow” was a biographical narrative film about the life of 1930’s film siren Jean Harlow and starred Carol Lynley. It was one of two films chronicling Harlow’s life that year, both with the same title – “Harlow.” The publicity war that broke out between Sargent and the producer of the the other film, Joseph E. Levine, was chronicled in a book entitled “Dueling Harlows” by Tom Lisanti. Thanks to the use of video equipment, Sargent was able to complete production in eight days and beat Levine’s version to the theaters. But even though the Electronovision images were technically acceptable, at least for a black and white feature, the rush to be released first resulted in a substandard production. The Levine version, released a few weeks later, was the better reviewed version. Sargent made money in spite of the critics because in those days he could do his own distribution. However, even with a substantial take at the box office, the company folded. But Sargent, convinced motion pictures produced using video were viable, would be back.

The “TAMI Show” also marks the first credited appearance of Joseph E. Bluth in a project connected with transferring tape to film. Bluth at the time was Executive Vice President of Mark Armistead Television, the supplier of the SECAM cameras and recorders for the “TAMI” show, and is listed as Technical Facilities Supervisor. The company also supplied the technical facilities for “Hamlet” as well. Bluth’s career goes back to the early days Los Angeles television. He is credited as technical director on the only kinescope known to exist of “The Buster Keaton Show,” a live local show originating from KTTV in Los Angeles in 1950. As I researched the companies responsible for developments in refining film to tape quality to make it more acceptable for the motion picture screen, Bluth’s name kept appearing.

In June, 1966, Bluth founded Vidtronics, under the Technicolor umbrella. In the mid-sixties, local stations could only afford one or two tape machines and if they were airing programming on those machines there was no where to put the commercials except the film projectors. Even when tape cartridge machines came into existence they were too costly for many stations (not to mention their initial reliability issues). Vidtronics’ primary mission was to make it easy for advertisers to shoot on tape and distribute on film.

Vidtronics demo reel from the early 70’s. Visual effects have come a long way since then.

Their new system involved making black and white separations of the video, enhancing them in the process and then using the Technicolor three strip film system (the same system used on “Gone with the Wind in 1939) to make the final composite. The process still used a film camera focused on a high resolution cathode ray tube to make the optical to film conversion and was not meant for use in motion picture production. In fact, in a blurb in the April, 1967, Journal of the SMPTE, Bluth makes it clear “…a print produced by this process is not suitable for theater exhibition because of the limitations of the NTSC standards for color television broadcasting.”

However, just three months later, the 3M (Minnesota Mining & Manufacturing) Company announced its Revere-Mincom division would offer a potential replacement for kinescopes. In a Broadcasting article dated September 12, 1966, 3M explained their Electron Beam Recorder would eliminate the optical step in the film recording process by allowing 16mm film to be exposed by a direct bombardment from the electron gun in a vacuum. About the process Broadcasting said it “…yields a sharp picture fidelity…[and] is said to produce motion picture film with improved resolution and reduced picture noise.” Initially, the system was black and white only.

This didn’t stop S. Bryan Hickox and Douglas V. N. McCutcheon from using a 3M Electron Beam Recorder to convert color tape to color film. In November of 1971, it was announced they had formed Image Transform, a company devoted to video conversions, tape to film being a major portion. Hickox, founder and president of the company said “the “transforms” as they would be known, will be capable of large screen theatrical display.”

In a paper published by the Journal of the SMPTE in February, 1978, entitled “Film Recording in the Image Transform System” it was revealed that Image Transform used the 3M Electron Beam Recorder as the basis of its tape to film conversions. While not releasing any of the company’s proprietary specifications, the paper does reveal Image Transform rebuilt a black & white EBR-100 from the ground up, breaking the video down into the primary colors as Vidtronics had done years before then exposing a single strip of film as a color separated master.

The exposure method had been used in the early days of Technicolor on cartoons starting with Walt Disney in 1937. It’s called “successive exposure” and simplifies the exposure process. Three frames of film were photographed through successive red, green and blue color filters to complete one frame of video. Then using a special printer, the color separated film negative was subsequently exposed to the color negative film, one color at a time. Ultimately, Image Transform had their EBR unit running at 72 frames/second (three times normal film speed so transfers could be made close to real time). The company also adjusted the machine’s electron beam so it eliminated the appearance of scan lines with minimal degradation of the resolution of the picture.

At the same time Image Transform was getting underway in Hollywood, a narrative film was in its completion stages outside of London. “200 Motels,” a film by rock and roll artist Frank Zappa was released in 1971. It was shot on videotape in the European PAL standand and transferred to film by Technicolor in England where a branch of Vidtronics was co-located. The transfer took place on a Technicolor 35mm film printer utilized by the BBC. Some sources credit “200 Motels” as the first feature transferred to film. As we’ve seen earlier, that is not case, although it may be the first color production to successfully go through the process.

In 1973, the first motion picture using the Image Transform process was released. “Santee,” was a western produced by Ed Platt (best known as the Chief in the “Get Smart” TV series) and starred Glenn Ford in the title role. It was shot on location and utilized new portable video equipment just becoming available from another startup company, Compact Video Services.

That same year, Joesph E. Bluth received a Scientific and Technical Award at the 45th Academy Awards for video to film transfer developments. A year later, it was announced he would be the new president and CEO of Image Transform.

In the meantime, Bill Sargent had regrouped in 1975 to form “TheatroVision.” By that time, videotape editing had become more refined and color had become commonplace. Sargent’s latest production was a recording of the one man play, “Give ’em hell, Harry” a show based on the life of President Harry S. Truman. The film led to an Oscar nomination for James Whitmore in the role of Truman. Bluth’s name was back, this time as a producer. That would indicate the film conversion utilized the facilities of Image Transform.

Sargent produced several other projects under the TheatroVision banner, but his biggest film was 1979’s “Richard Pryor Live In Concert.” From a production budget of $300,000, the film grossed almost $16 million.

Image Transform went on to transfer a few more big screen productions to film but eventually they were purchased by Compact Video Services in 1979. In turn, when Compact Video began having financial problems, it was sold to a New York investment group in August, 1993. The investment company consolidated all the units into one operating unit under the umbrella of Compact Video Group.

Shooting video for film release never really caught on until the advent of Digital Video. In 1995, Sony’s release of the their DCR-VX1000 3CCD color camera that shot Digital Videotape (DV) and interfaced via Firewire to a computer was the beginning of a tidalwave of change in the movie industry. Electron beam scan lines gave way to pixels. It was the crack in the door for the democratization of filmmaking. It also was the first step toward the cameras we accept today as “electronic cinema.”

It didn’t take long for the first filmmakers to take up the challenge. In the fall of 1996, the VX1000 camera and DV format got into the hands of aspiring filmmakers Lance Weiler and Stefan Avalos who made their film “The Last Broadcast” for a reported $900. Accordiing to some sources, it has made over $3,000,000. It is believed to be the first “desktop” feature film – shot with prosumer cameras and edited on a personal computer. Not an easy task to accomplish in 1996.

Weiler and Avalos looked at what it would cost to do a tape to film transfer of their finished film. The prospect of spending thousands of dollars they didn’t have made them think twice and look for other options. Why did they need to deliver a film negative? They had been reading about Digital Light Processing (DLP) developed at Texas Intruments. In 1997, the first DLP projector was produced. The buzz over “digital cinema” began, but as Weiler says, “…nobody wanted to take the first step. It was a chicken-and-the-egg thing.” Finally, they made a deal with a satellite company to simultaneously transmit their film to five cities across the U.S. and with a digital projection company that would supply projectors for their film anywhere in the world for two years. There would be no tape to film transfer. The Wharton Business School at the University of Pennsylvania wrote as part of their introduction to an interview with Weiler, “The movie became the first feature film to be distributed digitally to multiple theaters…”

On March 9, 1998, “The Last Broadcast” premiered at the County Theater in the filmmakers’ hometown, Doylestown, Pennsylvania (and a long way from Hollywood), on a Texas Instruments DLP projector. It was the first motion picture to not just successfully shoot and finish on digital media but ALSO the first to screen nationally with digital projection.

The era of digital acquisition had met digital projection and Pandora was out of her box. A lot of forward looking people building on the successes (and failures) of a lot of other forward looking people have brought us to where anyone can pick up an inexpensive camera, edit it in their home and project it in front of 300 people. It’s been more of an evolution rather than a revolution. But today when you sit in a theater and watch a pristine, scratch free picture, you have to wait for the credits to know for sure if it was shot on film – or with a television camera.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now