One recent example of how Fujifilm continues to explore the relation between film stock and modern sensors is visible on the Classic Chrome emulation, which tries to reproduce the ambience found in documentary-style photographs and magazines.

Contrary to what is usual, Fujifilm is not reproducing an existing film, as they have done until now, but producing something new in response to requests from professional photographers. The name ‘Classic Chrome’ reflects a mode reminiscent of the images each individual carries in their mind and the physical prints of such images.

|

Keeping film alive in a digital world This article expands on the notes I wrote for the article The aftermath of the film vs video debate – A PVC Roundtable Discussion, published recently”. I was already working on it before the roundtable and while it points to a different discussion within the theme, we felt at the time it made sense to refer to Fujifilm’s experience. Here you can read the whole story of how Fujifilm is trying to keep the memory of their emulsions alive inside their cameras. |

Shinya Fujiwara and Tetsuro Ashida, from the Colour Reproduction area in the Fujifilm Electronic Imaging Product Development Center, are the creators responsible for the Classic Chrome emulation, characterized by its colors and tones. They say that “when we analyzed relevant images, we were particularly struck by how tones in skies were reproduced so this became one of our key areas of focus. When the sky includes a hint of magenta, the resulting color is rich, but with Classic Chrome we moved in a different direction and created new colors by removing the magenta component. Classic Chrome also controls the saturation and hue of reds and greens to produce a unique chromatic balance.”

Creating a documentary-style chrome

In developing Classic Chrome, they continue, “we have listened to the opinions of professional photographers to create a new style of color reproduction. We believe this will provide X-series users with a new method of creativity and we hope photographers can put it to a variety of uses.”

The most frequent request the team received, particularly from photojournalists, was for a mode with more muted tones, so they analyzed hundreds of documentary-style images to find out exactly what kind of effect photojournalists were looking for. They reached the conclusion that good documentary-style images allow the photographer to put something of themselves into their work, so they created a Simulation mode that allows the photographer to tell the viewer a story. The team also took into account the recent trend for photographs to be viewed more frequently on digital devices rather than as physical prints and worked to create a mode that looks like a print when viewed on an LCD screen in JPEG format.

Classic Chrome, as any other film emulation in Fujifilm’s cameras, works with the camera’s image quality control features (including shadow tones and highlight tones) to match the scene and emotion, so users can achieve a broader creative range. Fujifilm feels that it is very important to listen to feedback from professionals and users of their cameras to further enhance their existing Film Simulation modes, so the Classic Chrome is probably not the last mode created by the company.

Fujifilm emulsions live inside their cameras

The Classic Chrome extends the initial set of five colour Film Simulation modes available on Fujifilm cameras, which include Provia, Velvia and Astia, designed to deliver the deep color tones of reversal film, and PRO Negative Standard to emphasize skin tones and PRO Negative Hi for natural light. The cameras also offer multiple options of B&W with filters, extending the creative options. For a photographer it’s very much like choosing a specific emulsion for a shoot, with a difference: you do not need to carry multiple rolls of film with you, and you can change style from photo to photo, something you would not be able to do with film. It’s an interesting concept, and something all photographers but probably photographers in some areas, like fashion, can explore in multiple ways.

|

The Super CCD EXR In 2008, when presenting the Super CCD EXR at Photokina, Fujifilm referred to it as a “three-in-one” sensor for high resolution, high sensitivity and wide dynamic range”, made by photographic specialists for photographic specialists. The revolutionary sensor was the way to celebrate 10 years of Finepix digital cameras. At the time Fujifilm pointed that while “there is strong demand in the digital camera market to increase the number of pixels on a sensor” most of the time used as a yardstick for image quality, that increase in pixel makes it more difficult to achieve high sensitivity and wide dynamic range. As the photodiode gets smaller, the problems of increased noise, blooming and clipping increase. Fujifilm believed to have found the solution through their program “Real Photo Technology”, which made possible to reconciliate, especially in small sensor cameras, eternal opposites: “high resolution” and “high sensitivity”. It is widely believed that “high resolution” and “high sensitivity” are irreconcilable opposites, and impossible to optimize on the same sensor, particularly for compact cameras, where sensors are necessarily smaller. Fujifilm engineers built the EXR sensor, a chameleon able to adjust its complex electronic behavior to suit the subject and the photographer goals. Again, the end-goal was to produce a sensor that works as close to the human eye as possible. In 2008 Fujifilm engineers wrote that “the direction in the future will be to combine HR and SR technology together to produce one universal sensor suitable for all high quality photography. But the Super CCD was abandoned. Did the dream die? No, we find it, at a new stage of development, in the X-Trans sensor used in the X series of cameras. So, the adventure continues. |

|

The experience Fujifilm has with film is put to good use in the digital world. Since 1934 that the company has been at the forefront of technology when it comes to film, and Fujifilm, which also had film cameras, with some exciting medium format, panoramic and rangefinder models, was one of the companies that first embraced digital, presenting their own cameras and sensor technology. For some time, their own DSLR models, like the Finepix S5Pro, built in partnership with Nikon, were favorite among social photographers, for the great colour reproduction they showed, and the excellent JPEG files created. Even today, in a time where RAW is king, many users of the recent Fujifilm cameras use JPEG, because of the results they get from that “baked” file format when it comes out from a Fujifilm camera.

Memory of colour

When it comes to colour, Fujifilm continues to focus on accurate colour reproduction, following in modern days the same philosophy they had with emulsions. I do believe that’s what makes them different. While camera makers as Canon or Sony develop systems with high-resolution, wide dynamic range, low noise, etc., Fujifilm does all that but prides itself on accurate colour reproduction, aiming to produce “memory colour” exactly as the photographer remembers seeing them.

Kousuke Irie and Shinya Fujiwara, respectively leader for color reproduction/noise and responsible for color reproduction/white balance/gradation reproduction at Fujifilm Electronic Imaging Product Development Center, say that “our Provia film simulation mode is the standard for color reproduction, which adopts ‘memory color’ for blues, greens and skin tones to accurately capture landscapes, portraits and general snapshots.”

As an example, the Fujifilm X-T1 camera offers Provia and four other film simulation modes that mimic the characteristics of each silver halide film. There are three reversal film modes: PROVIA can be used for various scenes, Velvia suits landscape photography with an emphasis placed on ‘memory colors’ for blue sky and greenery and Astia that aims for accurate skin tones and blue sky. In addition there are two negative film modes: Pro-Negative STD for smooth skin tones in the studio and Pro-Negative Hi when shooting with natural light.

A database of colours

The starting point for each one of these film simulation modes, according to Kousuke Irie and Shinya Fujiwara, ”is to adjust the target color value using a color chart in a studio. This is then tested in a wide variety of conditions both indoors and outdoors and revised accordingly. This process is essential as there are many kinds of light than can’t easily be reproduced in the natural world, such as UV and infrared rays, and even a small amount of these types of light can degrade color accuracy. Fieldwork is essential to overcome these issues and, in such circumstances, the actual image is assessed rather than the chart.”

On the information available, it is also mentioned that “for good color reproduction, it is essential to have accurate auto white balance (AWB) that automatically adjusts to the scene. Fujifilm’s most important consideration in AWB performance is consistency. Instead of showing 90% accuracy in one scene and 0% in another, we want to keep the average score high, even if it isn’t absolutely perfect.” Inaccurate AWB is usually caused by the camera mistaking the color of the lighting and a consistent performance relies upon the ‘light source detection algorithm’ which detects the lighting source. Fujifilm has an ever-evolving ‘light source detection algorithm’ which is based on a vast amount of data.

Much like color reproduction, AWB accuracy is, states Fujifilm “determined by a combination of test shooting various scenes and work at the design stage with over 10,000 picture taking scenarios assessed for each model. We have photographers both in Japan and overseas who take pictures for our database that is updated to ensure AWB is constantly evolving.”

In addition to color reproduction and white balance, dynamic range and gradation are also important to create fine colors. The basic dynamic range of the current X- series has been expanded from the one found on the Finepix S5 Pro and uses a gradation control system called Image Tone, which does in camera what would be done in the darkroom, through dodging and burning techniques, with emulsions, to prevent degradation of contrast and intensity of highlights and shadows.

Super CCD: where it all started

Fujifilm X-series cameras offer users multiple control options so the final image reflects their preferences. Film simulation, white balance, tone and dynamic range are some of the options available, making it confusing to some users, lost when faced with so many functions. Fujifilm advises users, in such cases, to select RAW shooting and process the results using in-camera Raw processing. The fact that it is possible to change each of these image quality controls and see the effect on the image allows to tailor results to user’s preference.

To understand why Fujifilm goes to such extent one has to look beyond the commercial reasons. In fact, Fujifilm’s history in the digital world very much takes a lesson from their experience with film, and that has been a goal since day one, it seems. Designing their own sensors, Fujifilm used their Super-CCD sensor since 2000, evolving it through different stages, until the seventh generation, in 2008. In 2003, with the fourth generation, they were already applying to sensors something they had done before in silver-halide film. Their new Super CCD had two versions: the Super CCD HR for ultra-high resolution, and the Super CCD SR for expanded dynamic range. The result: digital image quality that more closely approaches the perceptive abilities of the human eye itself.

Silver halide film is coated with crystals of various shapes – highly sensitive grains with large surface area that respond to small amounts of light, and low sensitivity grains with small surface area that respond to large amounts of light. The Super CCD SR achieves a similar division of labor by mixing low-sensitivity pixels (R-pixels) and high-sensitivity pixels (S-pixels).

The end of the road for Fujifilm sensors?

With the introduction, in 2006, of their 6th generation Super CCD, Fujifilm created a sensor offering good image quality up to 800 ISO. I remember it well because the results from a compact camera we tested at the magazine I wrote for at the time where so good we decided to use one of the images taken for the cover. The Super CCD capabilities in terms of low-light were, in fact, surprising.

The last generation, the 8th, of Super CCD sensor was launched in September 2008. The Super CCD EXR combined in one single chip the advantages of HR and SR sensor types from 2006. Although the new sensor seemed to be the corollary of many years of development, Fujifilm abandoned the Super CCD type of sensors, adopting conventional sensors, in 2011, surprising those that believed the Super CCD had a future (see text The Super CCD EXR).

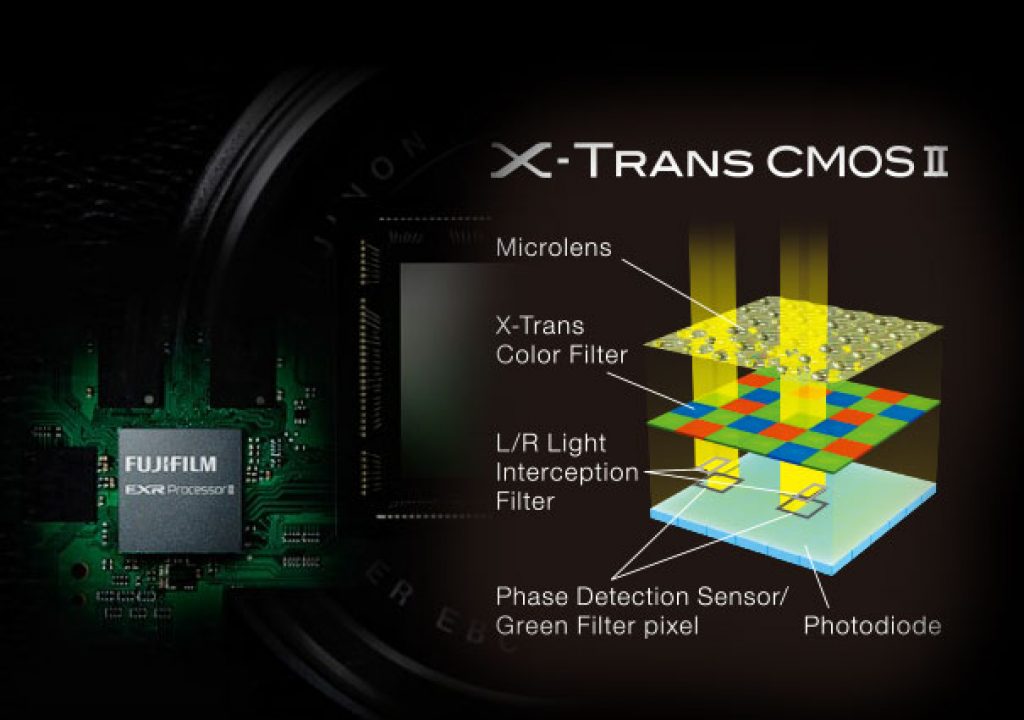

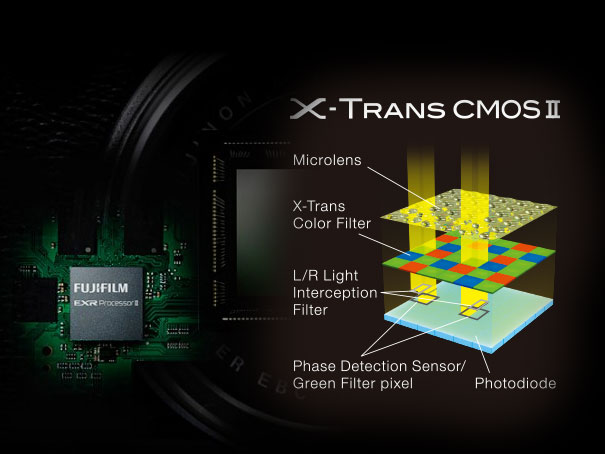

Although Fujifilm moved from CCD to CMOS, following, after all, the same path as the whole industry, the concept of the EXR technology was never abandoned. Within the X-series of cameras the processor for the system is called EXR, while the sensor receives the X-Trans designation. The documentation available for the first generation of the EXR processor states that the mission of the EXR CORE is to ensure that information received from the sensor is fully exploited without loss of any data; maximum resolution is preserved; detail and smooth tonality in highlights and shadow are revealed; and colour is naturally and faithfully reproduced. In addition, the EXR processor incorporates a reconfigurable processor. This processor that can dynamically adapt with rewritable circuits gives the EXR processor ample capacity to perform complex correction and processing tasks.

The adventure continues with CMOS

Fujifilm is already on the second generation of the technology, with the EXR Processor II and the X-Trans CMOS II sensor, and evolution continues. In 2008, when the first CCD EXR was launched, Fujifilm confirmed the determination to “use decades of imaging know-how gained through the development of film to push the boundaries of what is possible to achieve with an imaging sensor”. The market for digital cameras is only around a decade old, and Fujifilm believes that it is possible to follow the holy grail of “absolute image quality” in the domain of electronic imaging, just as it did with conventional imaging.

With EXR, Fujifilm said, we “can choose one engineering direction, rather than developing separate sensors for high sensitivity and high resolution. Fujifilm looks forward with excitement to introducing this sensor into its range of high quality cameras, and expects enthusiasts to see a quantum leap in image quality from anything they have seen before.”

In 2015, talking about the actual processor and sensor, Fujifilm states that the highest image quality and speed are goals of the project, so that users can take the best photos under any conditions. And adds that “This quality is what is demanded in Fujifilm products. Our basic stance of improving our unique technologies while striving toward better image quality remains unchanged.”

Fujifilm’s philosophy is present in their range of X cameras, which has grown, supported by a series of lenses that make the system a unique experience for those who love the classic design of some of the models – something already present in Fujifilm’s film cameras.