I spent the 1st half of this year releasing two films, a feature length documentary and a short film narrative (Becoming Fools and Fruitcake respectively). Through this process I’ve attended screenings and festivals of our own films and for others. I’ve also sat through several Q&A’s with independent filmmakers and although I love hearing how other creatives move through the process of producing their work I sometimes get increasingly frustrated with the fact that camera gear takes such a center stage while lighting, composition, sound design and production design take a distant back seat.

As important as camera and lens choice is for your production lighting, audio and composition are equally as important. I’ve seen quite a few films shot on RED, Alexa and high end Canon and Sony cameras that looked awful. They should have saved the money they spent on those high end cameras and lenses and invested in lighting and shot on a dslr, it would have at least looked better.

Many times in the moment of my irritation I thought about firing off a social media post to make a quick statement. But I thought it best served to compile my thoughts and turn these points into teachable moments. I’ll try not to make these posts long, there will be a few of them. But I want to make these tips easily digestible and things you can put into practice immediately.

Lighting Tips for Cinematographers

Part I: Foreground and Background Exposure

A common mistake I see with independent and young Filmmakers is not knowing how to light their scenes for foreground and background. Often they rely on setting a low aperture from their lens to create depth. However, properly setting your exposure for your foreground (or subject) and background will create the same affect and give you more options with your camera.

The general rule of thumb is to set your key light one step higher than your background. Of course there are some variations to this rule depending on style and genre. But I want to burn that rule into your brain, my subject must be lit one stop higher than my background. Say that to yourself until it’s the first thing that comes to mind when your gaffer asks you “how do you want to light this?”

Now, how do you do this? Very simple, get yourself a light meter (I don’t care if your gaffer has one already, every cinematographer should have one in his or her dity bag). Even if you have an app such as Cine Meter, it’s still a tool to aid you. Which ever you have, learn to use it (I’m not going to go into depth on how to use a light meter, there are plenty of YouTube and blog posts covering that subject) and then once you have a simple lighting rig set up meter your subject. Let’s say for example you get a reading at 4.0. Remember that and then move to your background. Find a flat area that faces your camera lens and meter that area. You should get a reading of 2.8. If not then adjust your lighting respective to your reading. If the background reads 3.2 then your a half stop too high. Consider a half scrim or pull your lighting back (or dim a half step if you have that ability). If you’re reading is 1.4 for the background then you must increase the power. Sometimes you have to adjust your key light in order to get the proper setting but no matter which method you have to employ, once you have this set, you will have a proper foundation to start with lighting your scene. Now, let’s look at some examples.

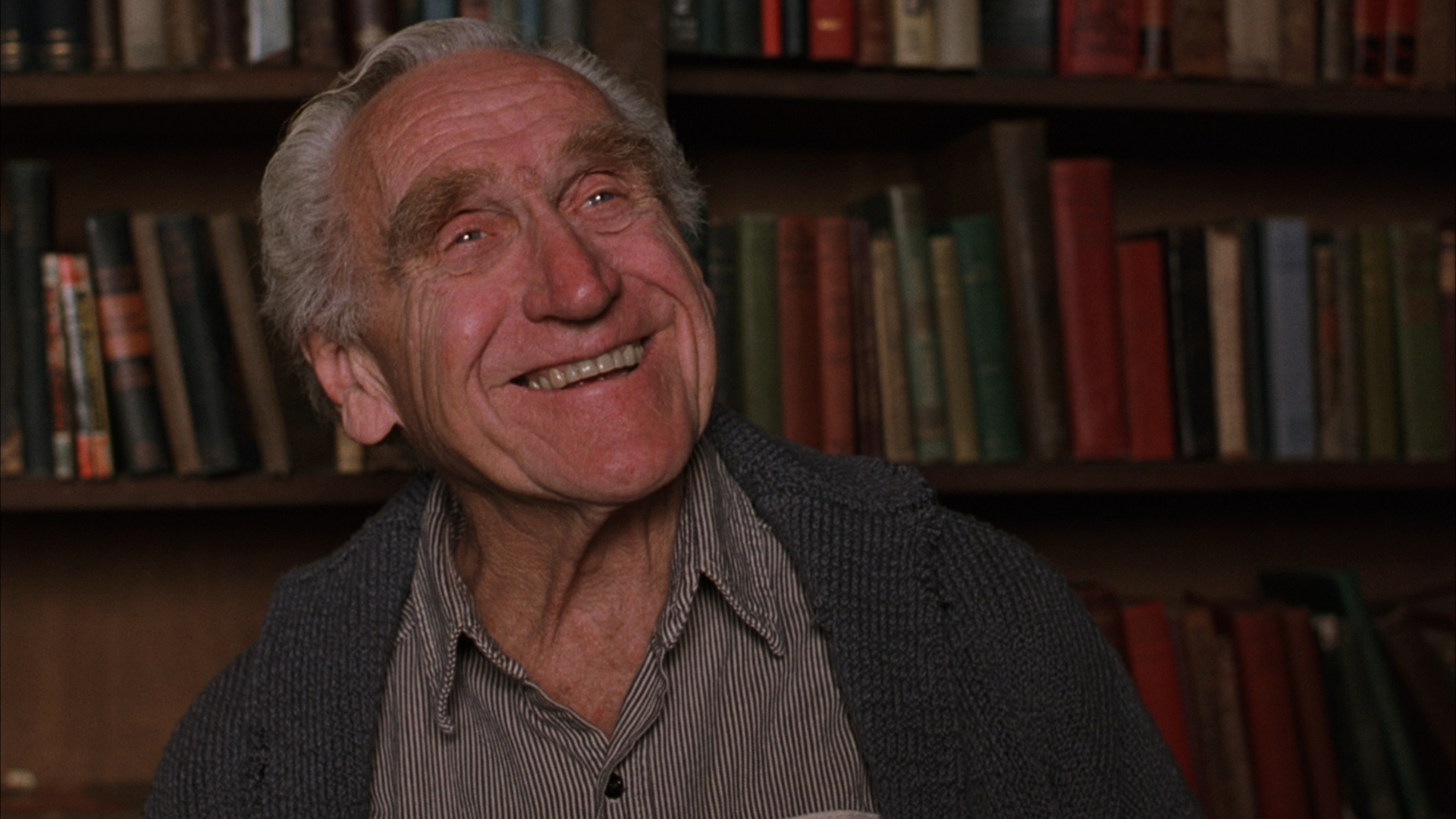

Shawshank Redemption (1994) Roger Deakins – DP

Here is a clear example. We have the subject that is not too far from the bookcase behind him in the background but notice how Roger Deakins (DP) lights the subject at least one stop above the background. Had he lit the background as much as the subject, even keeping the same depth of field, the image would have been flat and the focus for the audience would not have remained on the subject.

We Are What We Are (2013) Ryan Samul – DP

Here’s another example where Ryan Samul uses the same principle. His subject is lit at least 1 stop above the background, even though the texture is great, it’s not the focus of the scene so he chooses to keep the background dimly lit. Now, as I mentioned before employing this method is a start. Sometimes you want your background to play a role in the scene as it conveys an importance in relationship to the foreground and.or subject. So let’s look at some examples as to when this rule can be broken.

The Big Lebowski (1998) Roger Deakins – DP

Here you see the background of the grocery store obviously lit much higher than the subject. And if you also notice the angle in which Deakins uses the store shelves, starting in the foreground and moving towards the background. This is to show the deep philosophical nature of “the Dude” in the opening scene. It’s also to establish the environment in where he is. No one is around, he is isolated. You can assume that it’s the middle of the night when most people are not at grocery stores. So there’s a ton of information you can gather from this one shot and a reason why sometimes you want to break the one stop rule when lighting foreground and backgrounds. But at least you can see the lighting is not even so there is still depth to the scene.

Book of Eli (2010) Don Burgess – DP

Now here is a shot in which Don Burgess decides to blend the characters in with the background. Both the subjects and background are nearly in focus and lit almost the same. Why? Many times you want to submerse the viewer into the world in which your characters are living and here is a good example of that. This method of even lighting allows the audience to get a sense of the environment in which the characters are currently in. But notice there is still a lot of light and dark, between the object, even on the characters who are lit from only one direction. Burgess still employed depth but just from a side to side and not in Z space.

Like with most anything creative, there are rules to break and the “one stop” rule with lighting is certainly no different. But learn it first and then use the creative process to know when and how to break it.

Please feel free to let me know your thoughts. Should you have any questions, please feel free to leave a comment.