For the average free-lancer on a film crew, it all starts with making the deal. Each and every film is a unique job and each film is staffed by a collection of workers who must first form an agreement with the producers who manage the film. It begins as a verbal agreement—a simple phone call and a yes–that’s immediately followed with a deal memo and a contract. The position of DIT is a new position recently added, incidentally not without controversy, to the hallowed list of film crew. It is an acronym for the Digital Imaging Technician, who is the person charged with managing the technical aspects of the film, those that determine how the video and audio are being recorded and thus how the film will look and sound. This role is now doubly important because the technical decisions made by the DIT also determine the postproduction workflow. To many it’s just another strange name in a long list of strange names describing the film crew, names like Gaffer, Key Grip and Best Boy. But management by a DIT can determine the successful look of a film or limit it’s potential and can impact the budget even more so than the choices made by the Director of Photography and has become the frontier border crossing where science meets art in this industry.

Previously, there was no need for such a position. The technical aspects of film have always been the exclusive domain of the cinematographer and required only enough understanding to make one basic decision—the choice of film stock. From this decision all other variables become fixed. The film stock inherently defines the ISO, the speed of the film; the color balance—daylight or tungsten; the color saturation; the contrast and dynamic range; and the texture of the image—smooth or grainy. Any other manipulation of the image occurred later in the processing of the image by the lab and the coloring of the image by the color timer who prints the negative in the same way color photographs were printed for consumers before digital photography, leaving the cinematographer with only three very simple choices, the same choices that all photographers must make—framing the image, determining the exposure and focusing. Ah, but in those three choices lies the art, crude or sublime.

Most consumers think that the camera operator is the cinematographer or that the director of photography operates the camera. To be sure, they are both cinematographers, but the attention of the operator is limited to the camera and the assistants, while that of the DP is broadened to include directing the entire crew, which includes the camera team, the grips, gaffers and their teams, and the art department as well. Colors, all colors, affect the mood and the look of a film, and so painted set walls and wardrobe choices need to be integrated into the total look and meaning of a film. Where your eye goes, what you focus on, what you ignore can all be directed by color choices. How you feel about a character is a color choice as much as an acting responsibility. In it’s basic form we know that the good guy wears the white cowboy hat and the bad guy wears the black one, Lawrence wears white, Darth wears black, but color goes

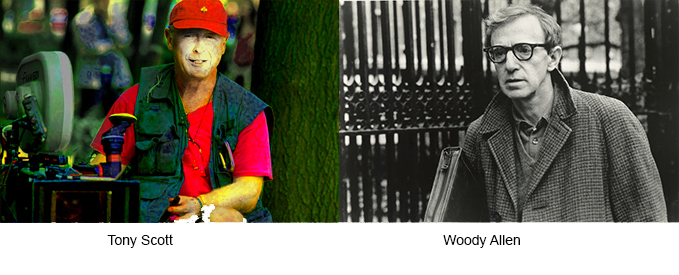

far beyond that. Color can make us feel edgy or calm. It can excite or titillate or create a feeling of sickness. It can signal health or disease. It can arouse anger, create hope or express uncertainty. A Tony Scott film is edged with disturbing color, while most Woody Allen films are shades of grey. It all means something that you understand at your deepest, most basic level.

As the DIT enters this sacrosanct mix and the technical responsibility in digital production moves away from a choice of film stock, to encompass every issue formerly associated with that choice, even an emotionally secure DP might feel threatened with the loss of authority and a lack of control. So married is filmstock to a DP’s vision that, recognizing this, Kodak named it’s most popular filmstock “Vision”. Thus, in the elimination of this bedrock choice, the move from film to digital represents nothing less than a frontal assault on the DP’s “vision” and a crack in the dyke separating professional DP’s from the wannabee DIYers (do-it-yourself-ers) who proliferate our below-sea-level landscape and continue to win film festivals by blindly ignoring every sacred rule of flood prevention.

To counteract this movement, film oriented DP’s retreat to their last bastion of defense, the mattebox, where they cling to the use of glass filters to provide some degree of control for color, contrast and sharpness. For those unfamiliar with production equipment, the mattebox is the device that attaches to the front of the lens to provide shade, flare protection and accommodate the use of glass filters. With the exception of graduated neutral density filters and polarizers, color modifications can be accomplished simply by a qualified DIT, with more potential and greater variation, sophistication and, there it is that nasty word, control.

For the DIYer, there are no restrictions, no rules to get in the way. With cameras that perform just about every function that an entire camera team on a major motion picture might perform—focus, exposure, color balance, audio levels—it’s not about skill but the story. For the professional DP working in a digital world, these same expressions that support story are filtered through the DIT and this is a source of recurring problems.

My selection as the DIT of this film came about as a result of my relationship with Panasonic Broadcast. Since the year 2000, I had been working as a free-lance director of photography on independent films, but I am best known for my consultancy work with Panasonic, which is largely very technical in nature. In addition to conducting seminars and speaking at trade shows, I created the “looks” for Panasonic digital cameras. Looks are files that can be read by the camera affecting a change in the color settings and hence the output of the image. From 2001 through 2010 I created all the color set-up files (or looks) for all models of Panasonic professional cameras. Since this film was to be shot on two of their flagship cameras, both VariCams, I was the logical choice to be the DIT. The Director was a former client and I had trained his staff.

Before leaving for a different production in Europe, he confided that the original DP for this film had become unavailable and no one had been chosen to replace him. In two weeks he would return and he was concerned about finding a new DP in the short time remaining before scheduled shooting. Mistakenly, hoping to be helpful, I offered my services in that regard (I had already DP-ed several independent films) and set in motion an undercurrent of events that continued to haunt me throughout the production process.

A few days after that discussion I received a call from his 1st AD requesting a demo reel. I had little to offer except a few scant clips on the internet as I was accustomed to getting employment by referrals, word-of-mouth from happy clients. What began as a casual suggestion to help a friend had now turned into a formal interview process to convince strangers of my abilities, a process I was both unprepared for and had little interest in.

So it came as no surprise that after several interviews with both the line producer in New York and the 1st AD, a DP was selected who had a proper demo reel.

In micro budget films (under one million dollars) every penny counts and so tedious negotiations continued, centering around my deal memo and rental agreements: adding gear, removing gear, trying to keep necessities, legal boilerplate, conflicts between the deal memo and the rental agreements, state employment laws, insurance, more legalese, more reductions, discounts, special rates, terms, shipping, travel, method of invoicing ad-nauseam.

It all became too much. I like to think that I have learned a few things over the years and one has been to walk away when something doesn’t feel right, and this didn’t. I declined their offer. To my surprise my cause was championed by the director who emailed the various producers that “If Mike quits, then so do I”.

Shortly after that I got a phone call from the executive producer. I knew I was being schmoozed by one of the best but I liked her take-charge approach. We had never spoken before, but as we were both from the same city, she began her conversation with a remark to that effect and in short time we discovered that we had something peculiar in common. Many years ago her grandparents had owned a theater in my home town that had since been torn down. At that time I had acquired 16 of the salvaged theater seats to use in a set that I was building for a national ad. Over all these years I have kept the seats and on that basis alone, and her excitement over the coincidence, I suddenly felt at ease, we resolved our differences and I agreed to serve as the DIT.

Once roles are established there is one significant choice that has to be made that is customarily not made by the DIT but remains exclusive to the DP, the selection of the type and model of camera. Unfortunately for our DP this decision had been pre-empted by our director, who owns the VariCam that will be used on the film and as I was the owner of the second VariCam to be rented to the production, it seemed to put me in direct opposition to the DP who wanted to use his camera, a RED One. In reality this was not a financial issue for me, as I also owned a RED One and could supply either camera as the second unit. The real crux of the matter was that the director had made the choice and that my job and obligations were to first support the director. This would come to a head soon, but cast me in a negative position with the DP, especially since he learned that I had also been considered for his position. This realization was interpreted as a mandate of sorts for his point of view, but more so, was probably perceived as a threat and a conflict. In truth, I was there to help him achieve his vision by supporting him technically on a camera he was unfamiliar with. Nonetheless, he seermed to resent my presence and repeatedly created barriers to the execution of my responsibilities.

But, I get ahead of myself. First the deal had to be finalized. After many lengthy phone calls negotiating my deal with the line producer and intervention by the production supervisor, production coordinator, first AD and production accountant I had little tolerance for the interruptive calls from the DP a young man who had no experience with the camera owned by the director and whose agenda was to rent his own camera to the production. Unhappy with the director’s choice the DP began lobbying me for support in his choice of cameras and after discovering that I owned both types of cameras and was renting mine to the production, a second unit “B” camera of the same type as the director’s, before giving up, tried to change the argument to technical issues regarding the use of a camera he was unfamiliar with and did not fully understand. Clearly he had a solid background in film, but equally clear was that he knew very little of the inner workings of most digital production cameras other than his own. So it goes. Now rather than setting the stage for cooperation, resentment and rivalry had been created by the selection process.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now