The Tech Retreat is an annual four-day conference (plus Monday bonus session) for HD / Video / cinema geeks, sponsored by the Hollywood Post Alliance. The program for this year's show is online at http://www.hpaonline.com/2013-program and the opening “Super-sized Session” was on “More, Bigger, but Better?”

Herewith, my transcribed-as-it-happened notes from today's session; please excuse the typos and the abbreviated explanations.

(During the rest of the week, you can follow the Tech Retreat on Twitter with hashtag #hpatech13, thanks to various Tweeters in the audience. I will of course post my notes at each day's end.)

Intro:

By the end of the year, predict we may not deliver any films on film in the USA.

3 new technologies, because “it's all about the story”:

1) HDR: we've been at 16 foot-lamberts in the theater for a long time, limited by flicker. Digital doesn't flicker (the same way); it's time for brighter pictures.

2) HFR: variable frame rates to tell the story. 48fps has been underutilized; not for everything, but useful. 48fps for 2D for greater immersiveness.

3) Immersive sound: $50-$100K per theater, so not cheap, but big, loud 7.1 sound (and beyond: object-based sound) really helps.

4K/8K? Not so much. Fine for production, display, not as important for distro. Hard to tell the difference from 2K on the screen [I'm not so sure, myself, but they didn't ask me! -AJW]

Leon Silverman:

We look longingly at bigger and better — yes, Virginia, size does count! How many Ks are OK? More res, more color, more dynamic range, more sound (5.1, 7.1, Imax, Barco Audio, Dolby Atmos all mixed for the new Disney Oz film). UltraHD is quad HD, 3840×2160, but true DCI 4K is 4096×2160. Bigger is better, but costlier; increased storage (4K adds 7-10% to the cost of VFX over 2K). Current HD / DPX tools need extension for higher res, wider gamuts, OpenEXR, ACES; move past proprietary color sciences and the “snowflake workflows” (HPA 2011; provideocoalition.com/awilt/story/hpa_tech_retreat_2011_day_1/) they engender. How to properly screen / evaluate these new media? How do we store it: “What is a Master? How does that relate to Archive? With so much stuff, where do you put the stuff?” 300 TB at the end of “Tron”. The new Oz film was 300 TB of compressed RED raw. At $0.01 per Gig per month (Amazon S3), 5 TB (a day) is $51.20/month; $300 TB is $3072/month… compared to storing a can of film: 12.5 cents a month!

4K for TV

Phil Squyres, SVP Tech Ops, Sony Pictures Television (SPT)

A case study of Sony's experiences in producing episodic TV in 4K. Is 4K the new 3D? Big topic at CES, seems more viable than 3D; already in cinema; easier to extend HD tools to 4K than to 3D.

SPT has shot 5 productions in 4K: “Made in Jersey”, CBS, DP Daryn Okada, F65; finished in HD. “Save Me”, NBC, DP Lloyd Ahern, F65, 4K finish at ColorWorks. “Masters of Sex”, Showtime, DP Michael Weaver, F65, 4K finish @ ColorWorks. “Michael J Fox”, NBC, DP Michael Grady, F65, 4K finish @ ColorWorks. Plus: “Justified” seasons 3 and 4 RED Epic 4K, DP Francis Kenney, delivered to F/X in 4K. “Justified” is a candidate for 4K remastering in future. “Breaking Bad” shot 35mm 3-perf, remastering in 4K at ColorWorks (season 2 in process). SPT will shoot 3-5+ pilots in 4K this year, either all F55 or combos of F55/F65 cameras. (All these examples are roughly balanced between comedies and dramas.)

Why 4K? Future-proof library for UltraHD. Creative reason: 4K raw capture gives incredible latitude, color space, freedom for blow-ups and repositions. Raw is closer to film; can treat more like film (latitude, color). F65 especially handles mixed color environments very well; don't need to gel windows or change practical lighting so much.

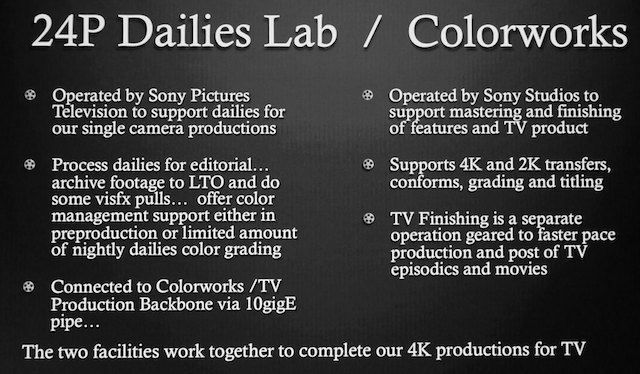

Bill Baggelaar, SVP Technologies at Color Works, says: shoot in 4K for the future. For sustainability of the post houses, transitioning to 4K is the way to go. ColorWorks designed from the get-go to support 4K for cinema, TV, remastering. Today's priority deliverable is HD, can't jeopardize it by focusing on 4K, so focused on tech that allowed 4K work with 4K and HD each being “just another render”. Centralized storage at SPT, the Production Backbone, allows conform and assembly of 4K assets in Baselight, seamless combination of 2K and 4K in Baselight, transparent upres/downres in postproduction, allowing HD workflow with a 4K render at the end of the day. Working resolution-independent: you don't HAVE to have a backbone, but you do need to be able to handle 4K data. ColorWorks partnered with FilmLight (Baselight's maker), but other tools work too. It's early days yet; things will get fleshed out. VFX for TV: some things better at 2K, some at 4K, depends on budgeting. Capturing at 4K gives better downsampling/upsampling for HD VFX (4K's oversampling makes a better HD picture).

Camera packages should NOT cost more. Cost of media can be moderated by investment (cheaper media such as SxS cards; SPT bought 150 SxS cards and reuses 'em; SPT buying F55 media the same way). Moving large files can be minimized by workflow design. New options reduce costs of grading and finishing 4K (e.g., DaVinci Resolve).

On set: F65 smaller, lighter than F35 or Genesis. Bulkier than Alexa but shorter. Epic and F55 are smaller and lighter than other large-sensor digital or 35mm film cameras. 4K is easier to shoot than 3D! SPT looking at combinations of F55s and F65s.

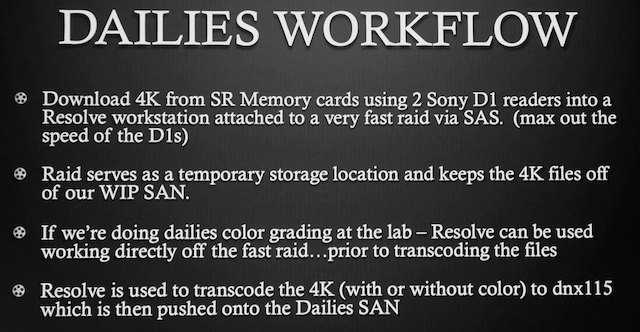

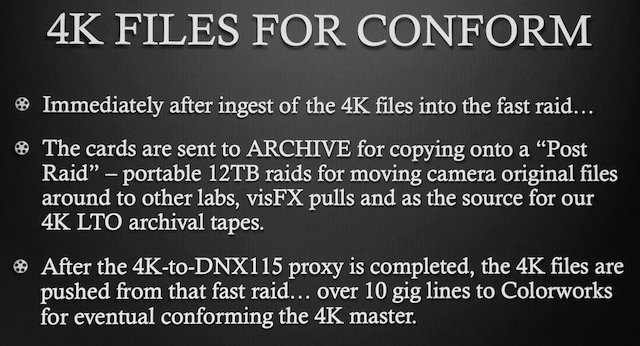

Media: for local shows, camera media sent straight to lab, no on-set backup. Typical F65 shows shoots 4 1 TB cards per day (not filling 'em up, necessarily; a card is about 100 minutes), two cards in each of two cameras, morning and night. No on-set wrangling, saves time and money; little chance of loss in transit. Consider buying cards, not renting.

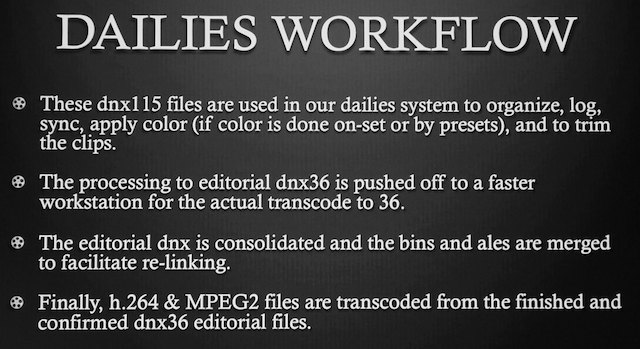

Out of town: experimenting with two optional workflows for local backups (was NEVER done with film or videotape, by the way, and we rarely suffered for it). 1: parallel backup with simultaneous HD recording. 2: parallel HD recording (in DNxHD 115 for “proxy”) with 4K local backup (near-set backup to 4K RAID, where it's kept until shuttle drive media are received at lab; don't need to overnight, ship once or twice a week instead, much cheaper!).

Dailies: processing 4K dailies is problematic! Opted to make a proxy copy early on; a proxy for HD editorial dailies. A challenge for onset systems, best done at lab.

Editing happens with DNxHD 36 on Avid, VFX pulls uprezzed as needed.

Why finish in 4K now? Why not edit in HD and hold the 4K for remastering later if needed? After all, no one is watching 4K TV today…

…but then you do the work twice; the second time is more difficult (learning this on the Breaking Bad remastering project). Always last-minute fixups and changes, not well documented (or ever documented); can be several hundred “undocumented fixes” in 100 episodes, and rediscovering the “recipes” for making the fixes and redoing them is very expensive and troublesome. QC takes longer than real time, adds 1-2 hours per episode for these fixes (just to find 'em, not to fix 'em!).

Thus the preference for today's productions becomes: Finish in 4K – IF YOU CAN.

Conforming: Avid Media Composer to read and organize EDLS and bins; Smoke to conform the Avid cuts and insert FX and fixes; Baselight for final conform (using original raw files) and grading. Traditional stages of finishing, but file-based.

Archive: 2 LTO sets made in dailies, of the 4K masters and the HD proxies and editorial elements. Once 4K pushed to the backbone, LTOs made of all 4K footage and mastering elements.

At this point, 4K doesn't take any more time than HD does. The only difference is the final assembly on Baselight and opticals on Smoke.

Q&A: What happens when 8K comes along? Breaking Bad may not be “for the ages” but it made sense for a 4K remaster, especially as we're set up for 4K digital work. What about the color issues? How to convey looks? One way: DP has a DIT creating LUTs, LUTs go to lab. LUTs / CDLs embedded in ALEs. Another way: DP created 5 looks beforehand, chose a look on set and lit to it, then those CDLs set downstream. Third way: design looks with colorist, share with DP. In all cases CDLs carried in ALEs and used throughout editing. Do you ever look at the 4K in dailies, or is all work done in HD? Proxies made from the 4K masters; if there's a problem in the 4K it'll show up in HD. No one edits in 4K today. True, you may not see some fine details in DNxHD 36, but it's not a huge problem. Eventually we'll edit in 4K and make HD a final deliverable, but today it's an HD-oriented workflow.

Immersive Sound / “Elevating the Art of Cinema”

Stuart Bowling, Dolby

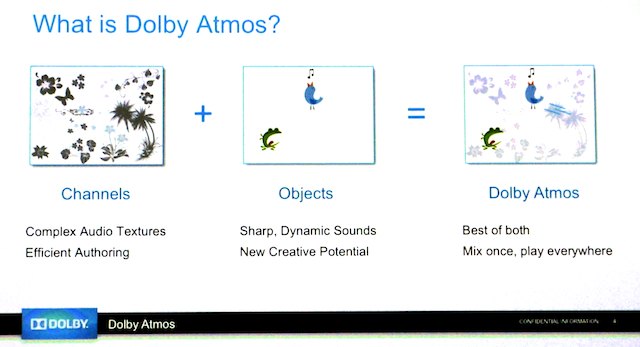

What's needed: better audio experience (richer palette, more artistic control); easy and intuitive (new authoring tools, fit current workflows), simplified distribution (single deliverable format for all different room types), scalable playback (for very different theaters). Dolby Atmos: arrays of speakers along walls and overhead; full-range surround speakers. Rows of speakers along walls, dual rows running down ceiling. “Channels” for complex audio textures, “objects” for sharp dynamic sounds; channels + objects = Atmos.

Authoring tools sit within ProTools 10, HDX, and HD-MADI. Sends 128 channels to Dolby RMU renderer, which feeds speakers. The theater renderer has a map of the speakers and maps the sound precisely to match the theater configuration. Working on console integration: AMS-Neve DFC in beta, System5 EUCON, JL Cooper.

Panel: Object Based Sound Design and Mixing: How It Went and Where It’s Going

Moderator: Stuart Bowling, Dolby

Craig Henighan, “Chasing Mavericks” (Sound Mixer)

Gilbert Lake, Park Road Post, “The Hobbit” (Sound Mixer)

Doug Hemphill, “Life of Pi”

Eugene Gearty, “Life of Pi”

Ron Bartlett, sound designer & mixer, “Life of Pi”

Craig, one of the first to mix Atmos on Mavericks: an eye-opening experience. Did 7.1 mix, happy with it, but Zanuck theater was being refitted with Atmos, so remixed for Atmos. Put 7.1 mix in the bed, wound up cutting New FX, the overheads really gave a better sense of being on the beach or in the waves, much more immersive. The real trick is subtlety, nice atmospheres, could put a seagull off to the left and have an echo off the back wall, Wind and water sounds, a wave splash; 5.1 and 7.1 quite frankly can't do this.

Doug, “Life of Pi” mixed in Atmos: also happy with our 7.1 mix. “Embrace the audience” with this speaker system. “Why no speakers on the floor?” “Americans spill their Cokes on the floor!” Ideas led to ideas… requires someone facile with the tech.

Eugene: Studios wanted more music, Ang Li wanted to let the actual sound tell the story. Simplicity. Impressionistic. It's not about hearing every detail, it's about making an impression. It'd be better to start sound design with Atmos, not reworking from a 7.1 basis. 9.1 channels, but within each channel an object can be placed very precisely. We thought it was just going to be about sound effects, but there was a lot of work moving the music around the theater, putting instruments in different places.

Gilbert, used Atmos on “The Hobbit”: wanted to match what 48fps did for the picture with sound. Started with simple panning, developed into a “creative wonderland” with so much possibility. New tech, wanted it to work with existing workflow; Dolby responded with EUCON integration with System5. Two rooms at Park Road, a 7.1 room and an Atmos room; simultaneous mixes as the schedule was so tight. EUCON automation meant 7.1 automation could be called up in Atmos room and reworked.

Ron: “Life of Pi” had a really great score. Went through the whole film, experimented; the composer liked the Atmos mix but wanted it pushed farther (putting choir in back, for example), everything we could do to envelop the audience (“give a hug” with the sound). For “Die Hard”, putting the sound IN the theater, not just along the walls and front. Made dialog clearer despite a very dense sound palette.

As the sound field increases in intensity, placement and localization suffer; Atmos helps preserve them.

Imagine the opening shot in the original “Star Wars” with that ship coming over; now imagine being able to do that same move with the sound. Great “bang for the buck” with Atmos; very cost-effective way to add production value.

With “Hobbit” there are giant FX sequences; you know you can do things with that. But it's the Gollum riddle sequence, story-driven, bouncing echoes off the roof of the cave, splashes and water drops, added more sound here than anywhere else. Nice when it's low-level. Also Bilbo and the dwarves in the cave, sleeping, putting each snoring dwarf into his own single speaker, for pure entertainment.

Exhibition is under a lot of pressure from competing media, Atmos helps bring the “special event” experience back to the theater in a way you can't replicate at home […yet! -AJW].

Q&A: Do you want to build a dramatic soundscape, or represent reality? Both, really. Can you bring in 3D object data from an animation system and use that as a basis for sound object placement? We start with the story; we let the movie tell us where to put the sound. Very much performance-based, audience-based, following our instincts.

Next page: what does the next generation want; premium large format theater mastering; 24p, and The Hobbit

Panel: What Does the Next Generation of Film WATCHERS Care About?

Moderator: Phil Lelyveld, ETC

Three USC Students represent the next generation:

Abi Corbin, MFA, Production

Althea Capra, Film & TV Production

Wasef El-Kharouf, MFA, Film & TV Production

Why would you go to a theater instead of seeing a film some other way? Wasef: Well, the irony of going to film school is you don't have any time to see films! So, I go to a theater if it'll show something I can't see at home. I'm looking for an escape; that why I enjoyed “the Hobbit”. The bigger the screen, the more detailed the sound, the darker the room, the better. Abi: grew up in Austin with a line of Alamo Drafthouse restaurant-theaters, very social. Here in LA, very different, least social way to spend time, so me and my friends don't do it much. Althea: saw a lot of films in theaters this year; it was a social experience: went back to Boston and went to theaters with old friends. Has to be something that draws people in; story driven.

[In the rest of this panel I didn't always catch who said what, so all the responses are lumped together rather than put words in the wrong mouths. -AJW]

Interactive pre-shows? Not so useful. Interactive world-building? The way we're going, very attractive. With interactive pre-shows it's like we're swapping what happens in the theater and the home. There are more people in the theaters, there are less theaters; theaters should be plucking from the home entertainment realm. The social aspect of the theater is enticing. Appealing that you feel you have some agency in how you experience the film (drive-in experience vs. Drafthouse experience). Transmedia: the future of entertainment. The ability for a story to grow past its primary medium is tremendous. Just look at how Star Trek has grown from just being a TV show (films, fan fiction, music, etc.).

Are 3D, HFR, etc. things you're looking at? These get me really excited. I want to design experiences; content is at the core of it, but any new form of medium informs the art and vice versa, reciprocal relationship. You can't rely on the tech alone to do the work. What makes me put down the iPhone and look at the screen? Will it further the purpose of the story, make the story come alive.

What are you learning in school? We had Michael Cioni from Lightiron Digital come in. Talked about using iPads in production; central storage for footage with on-set color correction. We're getting a whole arsenal of tools to make our imaginations come to life. We have a new professor in charge of digital tools. A lot of creators are intimidated by analog tools; digital helps enable them.

What about texting in theaters? It happens all the time. Was even an interactive film where you texted in suggestions; “I felt it was just another distraction.” “I like to text my friends during movies: 'what did you think of that cool shot?' (But then you miss the next shot).” Not too big a fan of second screen yet.

Spent much time in previz on films? It's huge. Can make script come to life before putting actors in it, can see what's working and fix things that don't. Valuable creative tool.

What personal devices do you have? iPad, iPhone; I watch films on iPad, not iPhone. We have 7 people in our house, and no TV (but we have a projector). For the most part, we watch on our laptops.

With all the high-res computer screens around, do you find SD or 24fps or other low-res media lacking? Yes, for me personally, but none of my roommates care: they're into the story. Ultimately if the content's good, it doesn't matter (others agree). I love a lot of those old artifacts, like film flicker. Now you have all the options: an artifact has to make sense in the story. My brother looked at a film I made: “why is it so dark and grainy?” And this is a brother who knows nothing about the tech. Would any of you make a B&W movie? Sure, if the story called for it.

What are you watching,if not TV? Netflix, Hulu. Netflix playing almost as ambience. Watching contemporary TV but not on TV? Sure, e.g., “The Office”. A lot of non-current TV on Netflix. It's not a routine thing to watch scheduled TV among my peers. The episodic experience is almost like an extended feature (“House of Cards” not bookended / no cliffhangers). We're still watching TV content, we're just not beholden to the original delivery system, “which is a horrible, horrible thing.” The stories are now structured differently. Just waiting for the whole series to come out, and then watch it all in one go. You're in the character's time frame.

Product placement vs. traditional ads? Some are OK with it, others not so much. Product placement only necessary if you stay with corporate-funded productions. Kickstarter raised $100 million for indie films this past year, and it's growing; think outside the box before we bend the story to house a commercial within the episode. I'll tolerate product placement more than ads, but a variety of options, I hope there's a better alternative. Maybe ads are that better alternative, but I don't want to make my story beholden to a brand.

Webisodes? “I'm a bit of a nerd and proud of it, I watched 'The Guild'”. Watched as a binge. Big fan of webisodes. Building a universe that may then lead to a larger-scale film. A lot of channels taking it into their hands to become mini-TV studios. Niche programming. Having content on YouTube that actually has a continuous narrative is pretty popular with my peers.

What's a way to pay for content (aside from pirating or getting it for free) that's acceptable? Everyone in our house has a subscription to Spotify or Mog. It just feels natural, like Netflix; OK to have access to content, don't need to own it. Depends on the media. Some songs I listen to repeatedly, I want to own that on my computer, iPhone, just have it play. Also have Hulu Plus with the Criterion Collection. Before film school, would have bootlegged it; now I'm a content creator, I'll pay for it! In music, you don't make your money off your albums, you make if off your shows. Similarly in film, you have to get us to care, to feel a bond, before we'll pay for it.

Panel: Mastering for Premium Large Format Theaters?

Moderator: Loren Nielsen, ETC Productions

Matt Cowan, RealD

Garrett Smith, Ha Productions

Ryan Gomez, Reliance Media Works

Sieg Heep, Modern VideoFilm

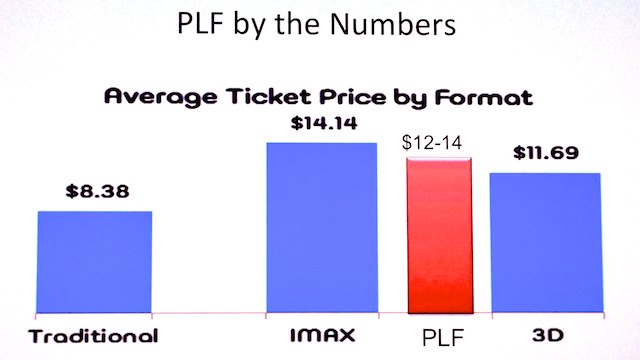

What is Premium Large Format (PLF)? Custom built, elegant luxurious high-back seats, immersive screens and sound. Examples: IMAX, XD, ETX, BigD, RPX. About 250 Premium Large Format screens exclusive of IMAX out of 41,000 total, generating 4-8% of revenue. RealD premium, then RPX, then IMAX in Regal's estimation (increasing ticket prices).

PLF auditorium typically high-backed seats, steeply raked auditorium, ideally 70 ft screen width minimum, 3100 sq ft screen size, seating 1x-2x screen height. Some using Barco immersive sound, some using Atmos, some just adding speakers.

Mastering? 4-perf 35mm (4/35), 5/70, 15/70; now digital: DR, res, brightness, color, clarity, bit depth, AE, frame rates, compression / lack of artifacts; 3D.

Image processing for PLF mastering: motion estimation / optical flow tracking for enhancing detail, noise reduction (the “Lowry process”). 3D processing; match one eye's color, alignment, etc. to the other (reference) eye, borrowing reference-eye data as needed. Super-resolution techniques; developed for SD-to-HD uprezzing, works great for 2K-to-4K too: upscales past target size, interpolates, then downsamples to target size.

(Clip from “Puss in Boots 3D” shown before and after Lowry processing, both at 4.5 foot-lamberts. From where I sat, about 6 screen widths away, there wasn't much difference to see; screen was as big as iPhone screen at half an arm's length!)

A DCP is like a 70mm print that can be played anywhere. It's what's in the DCP that matters: higher data rates, HFR. Built in: xyz color space and screen brightness. But mastering is done in P3 space. Color space translation needs saturation matching (among other things), use expanded color range for adding punch. 14 foot-lambert screen brightness built in, can't just boost it, like making a whisper a shout.

(Same clip from “Puss in Boots 3D” shown at 12 foot-lamberts (fL), first boosted but not retimed, the second time remastered for 12 fL. Huge difference; the first just looked bright, the second used the extended dynamic range to expand the highlights only, and it looked much better.)

Value proposition for PLF:

More light: brighter gives better color. Cinema brightness at 14 fL means much detail is around 1 fL, start of mesopic (night) vision, less color, blue shift. Better contrast perception, opportunity for brighter highlights. Increased “life” in the picture. 3D brightness is a key issue as 3D absorbs light. It there a useful limit to brightness?

(3 clips from True Grit, mastered at 14 fL, then timed for 21 fL, then timed for 28 fL. Huge differences: highlights expanded, and much more realistic. Audience thought 21 was perfect and 28 was too much; to this correspondent, the almost painfully bright glints off of snow and water felt completely authentic and believable at 28 fL… but 21 fL was fine, too.)

Better 3D: Retinal rivalry, edge violations, polarization differences (reflections, etc.). Needs work.

Detected problems: sharpness mismatch (often a synthesized eye view sharpens soft edges during rotoscoping). Flat planes (synthesis simply offsets an object instead of reshaping it). Hair cutting (again, in synthesized eye views, similar to fine hair dropout in keying).

More resolution: premium means sitting closer to the screen plane and seeing a magnified image. Pixels, artifacts are larger; errors harder to hide. Need more resoltuion just to stay in the same place. Visual acitity typically 30 cycles per degree, or 60 pixels per degree (Apple's “retina display” is around 46 cycles per degree). With 2K you need to be back about 3 screen heights, 4K around 1.5 screen heights, so 4K makes a premium seat work where 2K doesn't quite.

Premium viewing: multiple determinants. Nyquist limit. Viewing distances: NTSC 6+ screen heights, HD 3 heights, 4K 1.5 screen heights. (Sample images variously downsampled; where we noticed when it gets blocky depended on the types of scene detail).

24-fps Was No Big Deal

Mark Schubin, researcher

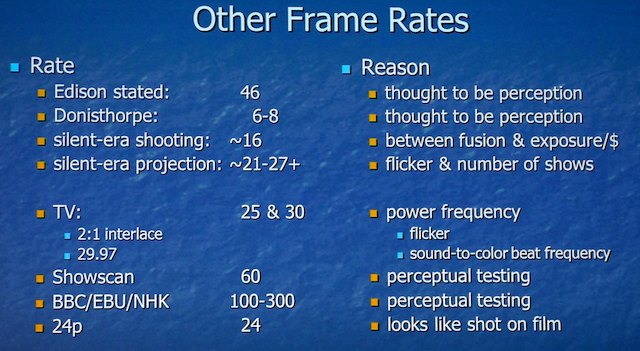

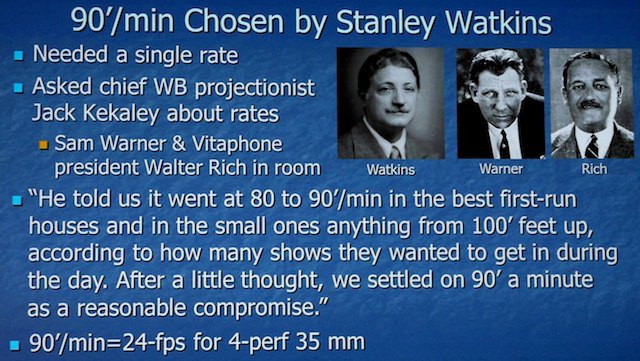

24fps not for sound quality; needed a single fps number; sound on Vitaphone came from a vinyl disc (at 33 1/3 rpm)!

The Hobbit: High Frame Rate Production, Postproduction, and Delivery

Ian Bidgood and Phil Oatley, Park Road Post

Park Road Post in Wellington, NZ, full service post house.

Why HFR? Better 3D, immersive, remove strobing problems. Pleasantly surprised with first tests in 2D. What frame rate? 48 is feasible, easily converts to 24fps. 60 fps possible, but hardware problems with display, complex downconversion to 24fps. 72 and beyond not technically feasible right now.

Tools: SGO Mistika DI finishing platform, RED Epic, 3ality Stereo 3D rig, in-house engineering on the REDs, including more cooling, fixing critical sync issues. All too easy to create subframe errors, made the footage useless. In-house software and code development for 3D 48fps workflow. Timecode for 48fps? Cuts only on A frames using 720/24P timecode with A & B frames for each timecode frame #.

Playback of first tests on dual DVS Clipsters to dual Christie projectors; looked rather nice.

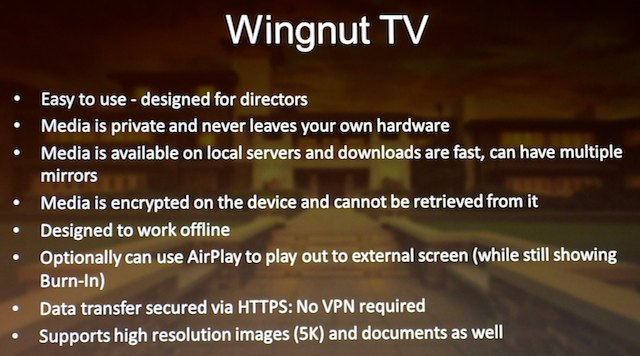

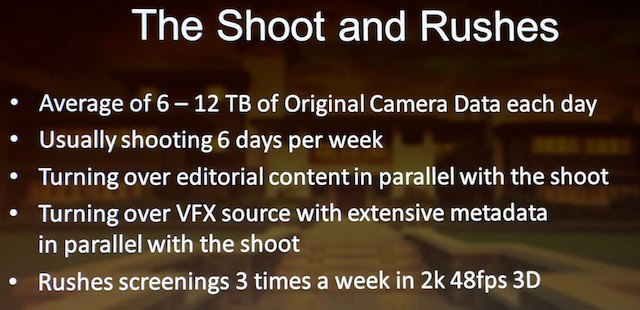

Workflow: LE and RE (left eye and right eye) data mags backed up to LTO, software matches the clips into a stereo pair (including frame offsets in the first two months of production). Each clip has a UID, plus a UID for each clip pair. UIDs sent back to Park Road even before clips were. Dailies: LTOs into a SAN, QCed, software generated a Mistika list, and another LTO was generated. Separate pipelines for stereographer and colorist, editing done on RE image as 24fps MXF, with uploads to iPad dailies-viewing system, too: Wingnut TV:

SAN management: each clip winds up with digi neg, MXF, align and grade data, and additional metadata, all bundled together. StorNext virtualized nearline storage (primary and secondary disk with tape backing).

Online and VFX turnover: clips sent to Weta Digital, returned clips placed back on SAN.

Mistika could handle 24 and 48 easily; after some testing of ways to get 24 from 48, settled mostly on “disentangle” (take mostly the A frames, with some Mistika motion estimation).

The DI: three teams, online / grade / stereo. Optimized for last-minute changes, teams working in parallel. Close collaboration with DPs, complex look-development phase. “The Grady Bunch” worked with DPs every day in the field, with mobile grading lab. DPs rarely came back to Park Road. Colorists first worked to bring shots into neutral balance, then added looks, expanded looks as time went on.

(We were shown DCP of a grade breakdown; original scene, primary grade, secondary grades, added filters. Often a very dramatic difference at each stage.)

The 24fps and 48fps grades are identical.

The delivery: tight deadline (of course!). It was epic:

Technicolor tasks spread across four facilities. Simultaneous export of all formats in real time from Mistika. DCP “answer prints” generated from Clipsters. Clipster data sharing allowed rapid changes. Additional deliveries to IMAX (about 48 hours/reel over the 'net). Delivery of all assets via Aspera over Sohonet. LTO took about 10-12 hours to generate all reels.

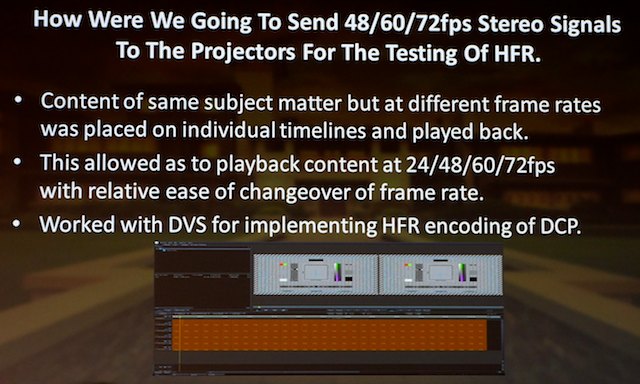

Getting it to the big screen: How to screen it for testing? No standards at the time to play HFR in a DCP. Capture system had to be pixel-accurate. Initially, two timecode-locked Clipsters feeding two projectors via DVI across fiber link, up to 72 fps from uncompressed DCPs (but too much data; had to reduce raster size to compensate, so that, and the reduced exposure time in camera, nixed 72fps for production).

Discussions early 2010 with server & projector companies about HFR. 3D test patterns made to check temporal artifacts, some camera-shot, others synthesized, including a Ping Pong test pattern: LE and RE blocks vertically aligned moving side to side. In single-projector system, there was always a lag between 'em.

Also needed to test pattern to stress JPEG2000 compression; used Sarnoff test pattern. 48fps 3D had to equal 250Mbps 3D 24fps images; needed 450 Mbps to get there.

Pixel-locked cameras needed; designed new RF sync locking system, with modified cameras. Each camera had its own sync pulse generator locked to master RF reference. But on set, lots of RF breakups, so had to handle sync signal loss, re-acquisition.

Dolby, RealD, and Xpand were able to modify their 3D systems to support 48fps 3D.

How much data was generated? 1.6 Petabytes (!) of camera original for Hobbit. But very light on the DI side, as it's all metadata.

All screenshots are copyrighted by their owners.

Disclaimer: I'm attending the Tech Retreat on a press pass, but aside from that I'm paying my way (hotel, travel, food).

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now