The fourth and final day of the 2010 HPA Tech Retreat started off with the vexing problem of TV loudness, and ended with an inspirational talk by Belden’s irrepressible Steve Lampen.

[Previous coverage: Day 1, Day 2, Day 3.]

(As usual, these are barely-edited notes, scribble-typed as people spoke. Screenshots are copyrighted by their creators; poor reproductions thereof are my own fault.)

Audio Loudness Panel, Moderated by Patrick Waddell, Harmonic

Jim DeFilippis, Fox – The New ATSC RP on Loudness and Its Impact on Production and Post

David Wood, EBU – P/LOUD and ITU-R Loudness

Steve Silva, Fox – Hands-On Experience with BS.1770 Loudness Measurements

Ken Hunold, Dolby – The Boundary Issue

David Wood, Ensemble Designs – AGC that Preserves Dynamics

Why do we now worry about loudness? Digital made it happen. In analog, on a good day, had maybe 40 dB of working range. Digital has >100 dB, and much less noise. ATSC started work on A/85 RP, the loudness standards, in 2007; published in 2009.

The CALM Act requires that commercials are no louder than the program around them; ITU-R BS.1770 (loudness measurement standard).

DeFilippis, Fox: worked on the A/85 committee. We also went from stereo, sort of, to 5.1 audio. Loudness is a complex sensation, e.g. fast talking “sounds louder” than slow speech at he same level. “Loudness is the quality that represents the overall perception of level”; it’s subjective and difficult to quantify. Dependent on environment, too.

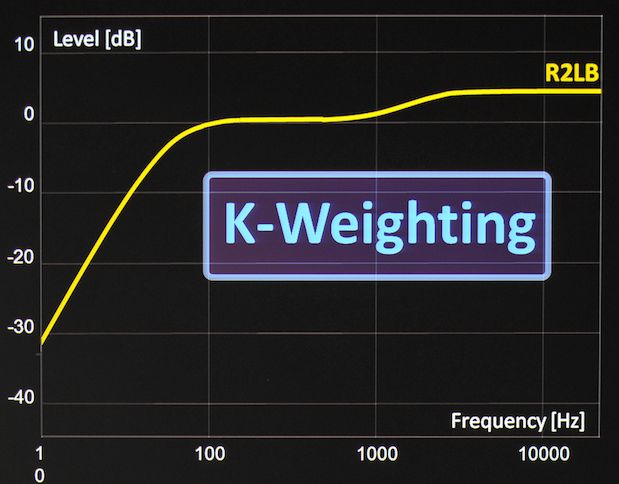

Objective measurements: CBS loudness meter. Leq(A), A-weighted loudness equivalent. LKFS (BS.1770), K-weighted loudness related to full scale, shown by subjective testing to come closest to perception. Frequency weighted average over the whole program, power sum across all channels in the program.

A/85 published on November 2009, referenced in CALM Act. Established common method for measurement, guidelines to mixers on how to meet “target” loudness (e.g., -24dBfs for Fox; in the absence of a network spec, -24dB is a good aiming point). Recommends that human monitoring in a proper environment is critical, five different environments listed, from headphones at 74dB to a 20,000 cubic foot room at 82dB. Important: verify mix on small speakers; in stereo; in mono. Strong 5.1 surround channels can overwhelm the center dialog track when downmixed to mono or stereo.

How to do it: long form: measure your dialog level and record that as your Dialog Level. Short form (e.g., commercials): measure the loudness of all content on all channels. Use qualified BS.1770 meter. Live mix: level the dialog at the target level, mix other elements to a pleasing balance.

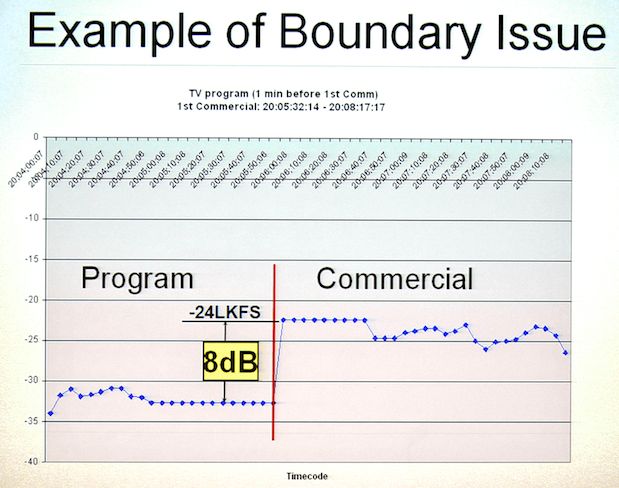

Loudness is measured on the anchor element (e.g, the dialog channel), but the anchor element may drop below average level; this is OK if it’s appropriate (quiet passage w/o dialog). But don’t let the short-term levels at program boundaries get too far away from the average, because the cut to commercial will be jarring.

Golden Rule: make sure your BS.1770 measured loudness levels match desired dialnorm value.

Wood, EBU: The past was a QPPM (quasi peak program meter), 10mS reaction time, didn’t match human perception well. In analog, you had space above headroom, so everyone pushed levels to the top, with compression.

But now the EBU (European Broadcasting Union) has tackled the problem:

Studies done in Canada (“listening tests not done by moose”) led to ITU.R BS.1770.

1 LU (loudness unit) = 1 dB. “Gating”, the concept of foreground loudness and the need to cope with it: programs with wider dynamic ranges, with the same average loudness as a flatter program, will have more apparent “foreground loudness” at the peaks. Gating out periods of quiet passages to avoid this problem took a lot of testing. Four levels tested: -8 LU below momentary (400 mSec) measurement window was chosen for now. Loudness meters should have an “EBU mode” where they all do the same thing. Suggest terminology change from LKFS to LUFS, “but Jim DeFilippis might have a heart attack!” Windows: momentary 400 mSec, sliding 3 sec, integrated is whole program.

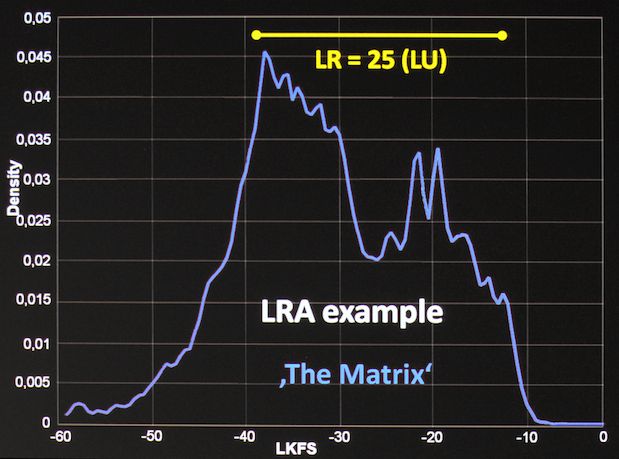

LRA (loudness range), excludes lowest 10% and highest 5%, measures statistical distribution of loudness levels.

Distribution guidelines need to account for differing STBs and output modes. Content supply guidelines must address migration scenarios if legislation sets a new number (changing what’s acceptable overnight), how to monitor, what needs to be changed. Main recommendation R128 with 3 parameters: loudness (-23 LU gated, +/-1 LU for live programs), maximum true peak (-1 to -2 dBTP), loudness range descriptor (metadata if possible).

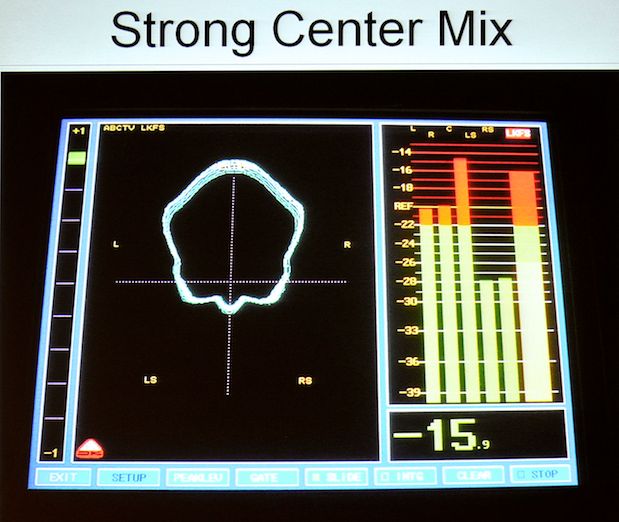

Silva, Fox: Using the Dolby LM100 (BS.1770) loudness meter. Lots of complaints about loudness both between and within programs. Need to measure, both subjectively (ears) and objectively (LM100). LM100 started out with Leq(A), firmware switched to LKFS in 2008. Measured loudness internally at Fox, at satellite downlink and at ingest stations. What modes to use: infinite or short term? Chose 5-second windows. Found there was no simple, single measurement type that works every time, so used two LM100s set up differently. Found Leq(A) matched LKFS within a dB or two. Measuring center-channel dialog as the sole anchor element didn’t work on more sonically-rich material. When to choose center vs all? Center doesn’t work for wide DR (dynamic range) shows, but all-channels numbers don’t help anyone without an LM100. But all channels measured in infinite mode gave overall loudness; easiest approach. Transition between programs / spots still the hardest thing to fix.

Hunold, Dolby: Measured 70+ programs from four networks (ABC, CBS, NBC, Fox) Sep-Oct 2009, Feb 2010. Used Dolby DP600 program optimizer, media meter, LM100; BS.1770 algorithm. Measured loudness, transmitted dialnorm (dialog normalization metedata; essentially indicates the level the program has been mixed to), peaks, etc.; plotted overall network loudness, commercial loudness, program/commercial difference, etc. Program loudness varies from -16 to -32 LKFS, mostly clustered around -25 LKFS, slightly better then in 2008 but not hugely. Commercials centered around -24 but weighted louder.

- Network W: programs typically 0 to 5 LKFS hotter then dialnorm. Commercials -1 to +12 louder.

- Network X: programs -6 to +5, commercials -6 to +7, avg +2.

- Network Y: programs -4 to +2, commercials -6 to +4, clustered at 0.

- Network Z: programs -3 to +2, commercials -7 to +9, very wide range.

Clearly, more work is needed.

Loudness processing: one station used loudness processing; made progam/commercial cuts more consistent, but compromised program DR.

Strategies for stations: Measure and tag: measure loudness, set dialnorm metadata; measure and scale: change gain to match metadata / dialnorm; target and evaluate: content that doesn’t meet spec is simply rejected.

Wood, Ensemble Designs: Audio AGC in the “real” world, or, How do you get the numbers right when all you have is a rubber ruler?

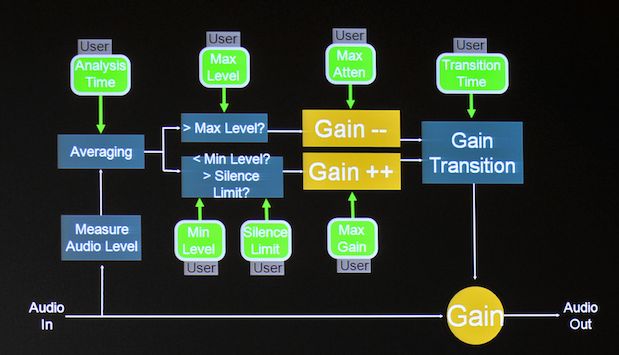

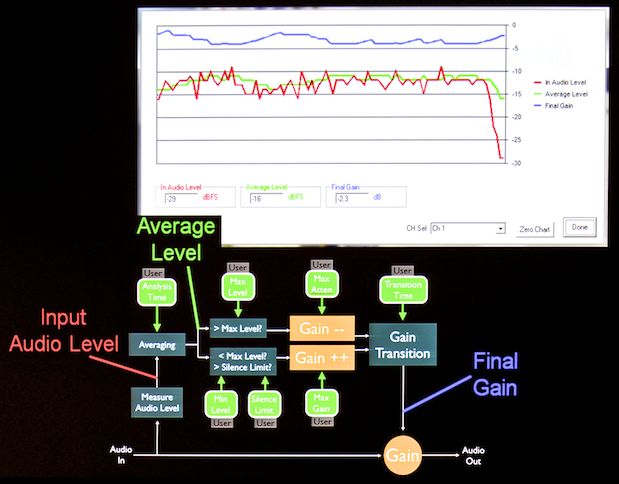

Avenue LevelTrack automated AGC: adjust the gain but don’t compromise the dynamics.

Tools exist, but not everyone uses the right tools at the right places; “The future is here. It’s just not evenly distributed.” – William Gibson

Many user controls for max/min levels, integration time, etc.:

System includes real-time graphing of instantaneous and average levels, and the resulting gain setting:

“People find that this system works; the controls let them finesse the AGC to match the kinds of content they’re broadcasting.”

Discussion:

• Are we heading to a North American practice and an EBU practice? No easy answer; there may some alignment between different countries/organizations. But there isn’t a lot of difference between our approaches.

• CALM has been modified to address commercial loudness AND program/commercial loudness consistency.

• What happens when you have a soft element and a loud element (“Star Wars” vs. “Love Story”)? You still wind up measuring levels and normalizing.

• What about local vs. network commercials? Not measured, but suspicion is that the local spots may not have been normalized as much.

• “We’re not just talking a few dB, we’re seeing a 14 dB difference: egregious!”

• Having a common set of guidelines is a critical point; advertisers don’t need to be the loudest, they just don’t want to be the softest!

• It seems that (from a guidelines standpoint) EBU’s loudness range is similar to ATSC’s dynamic range.

• “My commercials at home come from three sources: network, local insertion, cable headend. Levels are all over the place!” NCTA has been following the discussion, but there are thousands of MSOs with engineers who need to be brought on-board.

• What about inter-channel loudness? What seems to happen is that station engineers in a market notice a mismatch and work together to even things out.

Michael Bergeron, Panasonic – Reducing Operational Complexity of Stereoscopic-Production Camera Systems.

We’ve been looking at what people have been doing with 3D cameras for ages—maybe a year and a half! Right now, 3D equals stereo glasses for the most part. Passive glasses and micropolarized screens (e.g., line-alternate polarization screen overlay) gives half-res; active-glasses alternate-image systems give full res.

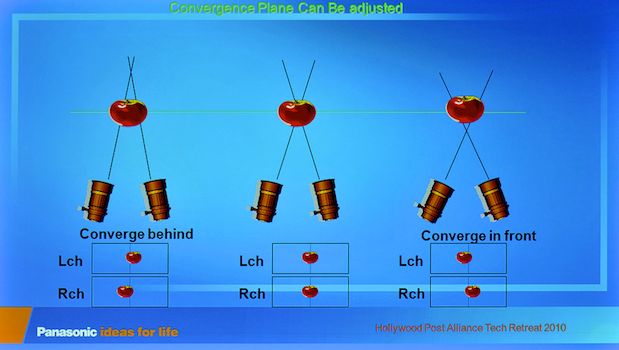

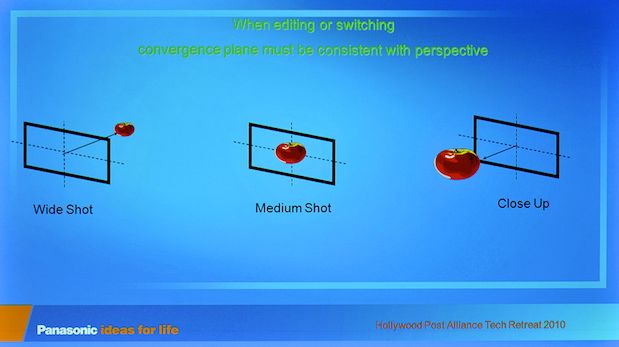

3D cam system must (1) link and sync two cameras; (2) manage parallax or two images; (3) correct optical and parallax errors for good 3D (e.g., fix all problems in the first two things). Getting that last part done is one of the big roadblocks. For (1), lenses must be linked and matched very carefully. (2) Parallax (convergence) management: should convergence track focus? Not necessarily; convergence must be consistent with perspective: close-ups should be closer than wide shots irrespective of focus:

What about IO (interocular, a.k.a. interaxial)? Too narrow, too little 3D effect; too wide, exaggerated and even painful 3D. IO and convergence angles are also constrained by / interrelated with object size, nearest & farthest objects, camera placement. Close shots need tighter IOs, farther shots allow / suggest wider IO. Fixed IOs just limit how close your closest object can be. Scientific research is good, but it’ll also help to just put cameras out there and see what happens.

Side-by-side rigs: limit minimum IO, tight CUs (close-ups) are a problem, minimum IO depends on imager/lens size, but simple and easy to make.

Beamsplitter rigs: no limit on minimum IO, good for CUs, but beamsplitter acts as a polarizer (and you lose a stop of light), and it’s mechanically more challenging to align and keep in alignment.

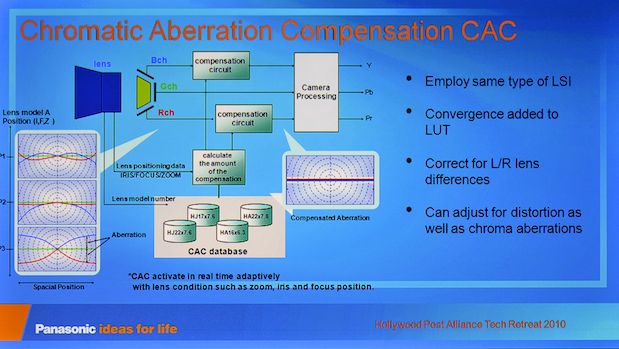

Optical/parallax errors: vertical misalignment; magnification differences; different L & R distortions (and different focus planes). Perfect images aren’t needed, just images that match each other. Ways to reduce these errors: optical/mechanical (pricey, not necessarily possible in all cases); postproduction (not useful for live TV; can be expensive); realtime electronic processing (typically expensive).

Current 3D rigs require a lot of engineering expertise, and skilled operators. Can we scale this down? With an integrated system with a fixed IO, this gets a lot easier; integrated lenses can be tracked at the factory; consumer cameras are already fixing optical problems in realtime. “Operation should move from ‘Guitar Hero Easy’ (focus, zoom, iris) to ‘Guitar Hero Medium’ (focus, zoom, iris, convergence).” It’s not really different from what’s been happening to get integrated camera/lens systems in 2D (in terms of managing complexity and solving optical problems electronically).

Small imager allows close IO (and deep focus). Lenses tracked during assembly keeps cost down. CA correction:

Why this (1/4″, prosumer-looking) camera first? (And by the way “it’s not a consumer camera!”) The biggest 3D bottleneck is a lack of skilled operators. Buy getting this camera out as cheaply as possible, we get more people trained up on 3D. Like Google does: just go out and collect user data. “A lot of people will shoot a lot of bad 3D (marketing told me not to say that!).” But we’ll all learn from what people do with this camera.

We don’t know everything about this camera yet: IO distance isn’t yet set, nor is sensitivity, max convergence, zoom range.

Next: Sony and Adobe; demo room wrap-up; final thoughts…

Hugo Gaggioni & Yasuhiko Mikami, Sony – 4K End-To-End

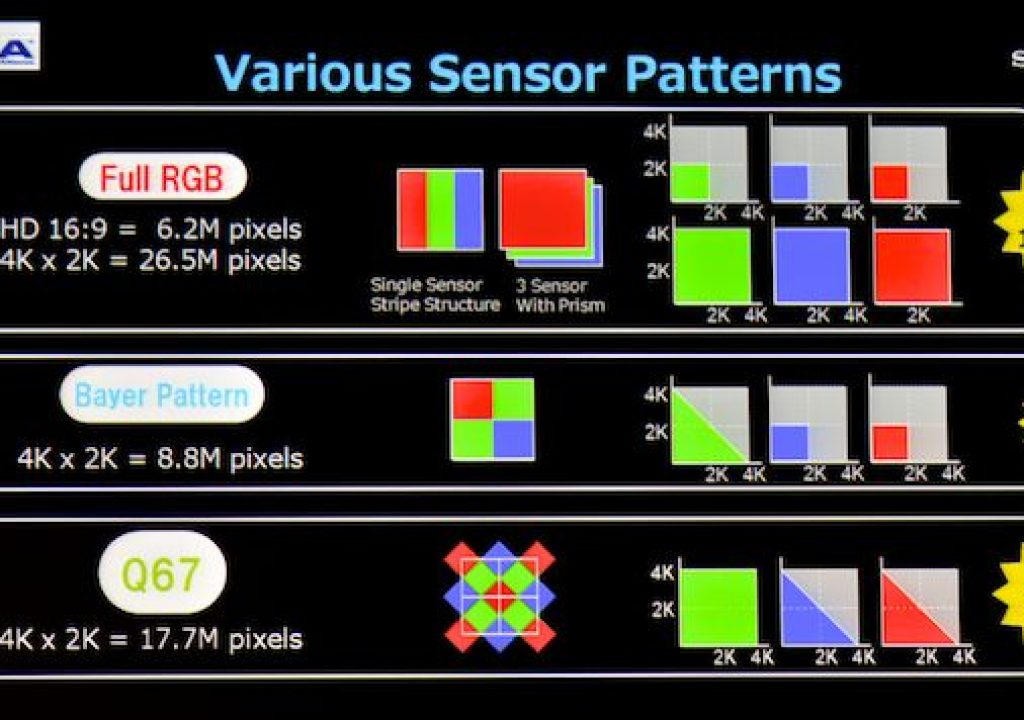

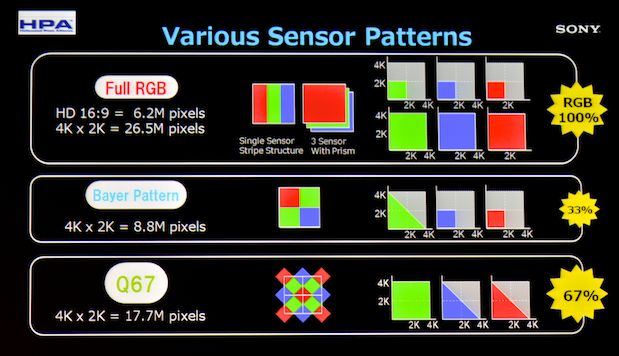

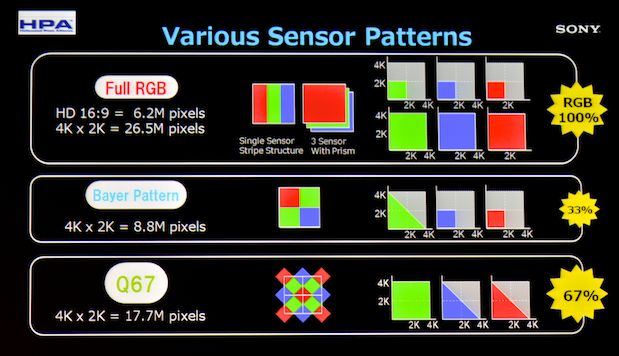

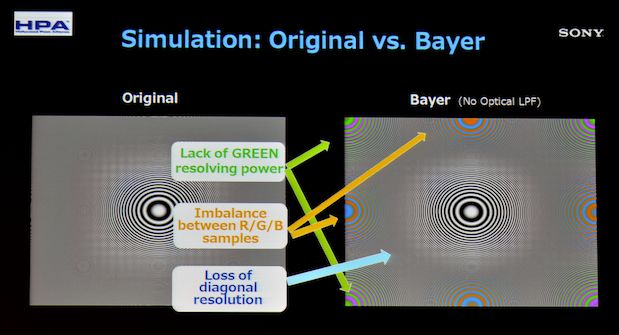

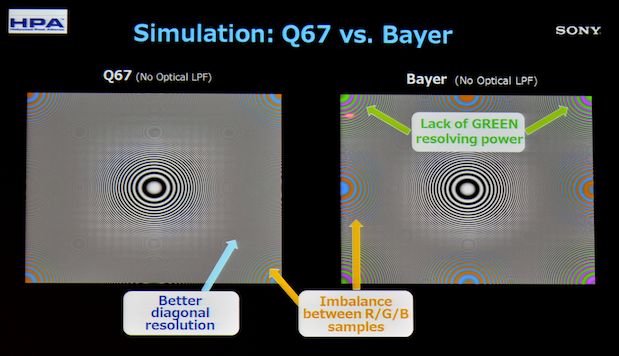

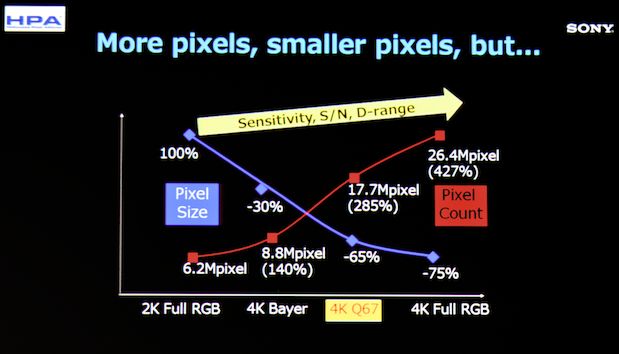

New imager sampling structure: We have stripe-mask (F35), 3 sensors with a prism; both capture 100% in R, G, and B. Also Bayer mask; 1/3 as much data as full RGB, but 33% the resolution. How about Q67: Quincunx 67%?

Advantage of fewer chroma moire artifacts.

CMOS characteristics: jellocam from rolling shutter; various sensor-specific fixed-pattern and random noises requiring in-camera fixes.

Full RGB sampling is desirable, and Q67 gets close.

CMOS needs work but is getting closer to CCD.

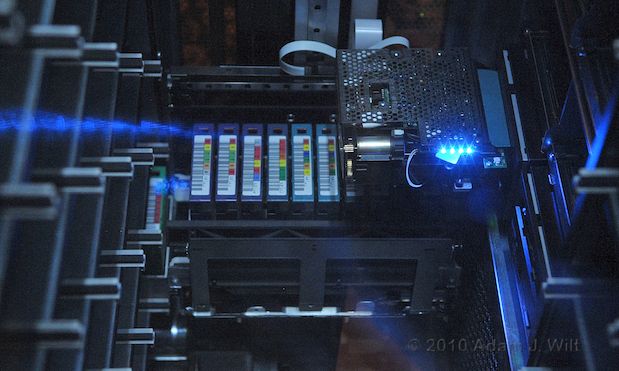

High speed storage: SR memory, 5 Gbit/sec:

Hugo Gaggioni looks on as Yasuhiko Mikami shows off an SR solid-state module.

SRW-9000 will get SR solid-state recording, 35mm sized imager with PL mount.

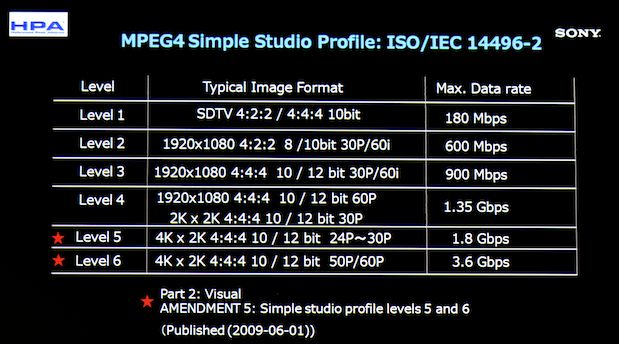

Codec developments for HD, 2K, 4K: SR uses MPEG-4 simple studio profile (SStP)

HDCAM SR tape machines use levels 1-3, higher requires solid-state storage. New generation ASIC offers HD to 4K, all the way to uncompressed, adds SR Lite @ 220 Mbit/sec (SR already has 880 Mbit/sec HQ and 440 Mbit/sec SQ). Lite is designed for high quality TV without too much color grading & manipulation.

Moving towards editable, native SR files, wrapped as DPX or MXF. SRW-5800/2 (portable SR tape recorder) will offer MXF and DPX outputs, 220/440/880 Mbit/sec recording.

There will be a software-only player; for compression there will be a PCIe codec card for 2x ingest.

ELLCAMI project: universal transcoder with either Intel or Cell based motherboard, up to 16 Cell CPUs, 3.2 TeraFLOPS. “Anything-to-anything”, including new DEEP (Dynamic Element Expansion Protocol) upconversion tech running on Cell CPUS: SD to HD, 2K to 4K, blur-free, jaggy-free, etc. Uses wavelet analysis, synthesizes high-frequency texture elements.

4K projection is here, but not much content yet. Higher res requires orchestrated development of optics, electronics, sensors, etc.; standardization is key (SMPTE, AMPAS, ASC, other manufacturers).

Qs: Will DEEP be available for other CPUs, other vendors? “We’ll talk.” SStP open? Yes, SStP is an open standard. More Q67 data? Don’t even have a sensor yet: may be a good subject for HPA next year!

Aseem Agarwala, Adobe – Three-Dimensional Video Stabilization

Project motivation is tracking shots like the opening of “Touch of Evil”. Walking is a hard thing to stabilize: traditional stabilizing filters smooth it out, but it doesn’t look like a tracking shot. Most 2D stabilizers estimate motion, then fit a full-frame warp (homography, rotate/scale, etc.) that minimizes the jitter. But homography can’t model parallax, doesn’t know actual 3D motion path.

“Traditional” 3D stabilization derives 3D structure from motion, creates 3D point cloud, then plots a new camera path through the space and renders a new scene, usually combining/averaging nearby frames. But this winds up with jumps, judders.

Adobe’s improvement requires 1:1 input:output, frame-for-frame correspondence. Segment out layers, determine depth, shift and re-compose, fill holes. But can’t be totally accurate; insufficient data for complete accuracy.

Can we cheat? Aim for perceptual cleanliness, not complete accuracy. Use “as rigid as possible” deformations, image retargeting (as in Photoshop CS4’s image resizing without element distortion).

Take input point cloud for a frame and the output point cloud, perform content-preserving warping with least-squares minimization (trying to stay close to similarity transforms: uniform scaling, translation, rotation).

These content preserving warps can fake small viewpoint shifts, and the human visual system is surprisingly tolerant of remaining errors. But it’s time-intensive, a bit brittle, requires enough parallax to see/derive 3D geometry (so long shots without a lot of motion are troublesome), and rolling shutter is problematic.

New work (not yet published): subspace stabilization. How do we get these 2D displacements better? Take all tracked 2D points, low pass filter them? No good: trajectories don’t track, so image gets very distorted.

Is there something more lightweight than full 3D reconstruction? Track some feature points, put into big matrix; matrix should be of low rank. Factor the matrix into eigen-trajectories, plan smooth motion through those trajectories, remultiply it back out, get a new low rank matrix with smooth motion. Isn’t baffled by lack of parallax or a rolling shutter.

The demo videos screened show dramatic reduction in jellocam artifacts, and looked superbly smooth. Adobe is onto something here.

Works on streams; doesn’t need the entire content in memory at once (but does require low-pass motion filtering is not all content is available at once).

Some of the Qs:

• 3D? Multiple cameras make stabilization easier, due to more info. Haven’t tried on stereo yet, but will.

• New algorithm is sparse-matrix algebra? Parallelizable? Yes, but that part’s very fast already; the hard part is point tracking.

Steve Lampen, Belden – The Joy of Wire (Post-Retreat treat)

Mr. Lampen gave an amusing and inspiring talk about being open to new ideas and asking the right questions, ranging from the Aztec game of Tlachtli (which used a rubber ball; when Europeans saw this, they neglected to ask how the rubber was cured, and so lost the secret until Goodyear re-created it… and rubber is used to insulate cables!) to the periodic table of the elements (stellar fusion progresses from lighter elements to heavier, stopping at iron; heavier elements require greater pressures, like supernovas. Just think: copper is used for cables! That copper cable was born in a supernova… just as the elements in you were).

Some quotes from his presentation:

“When you exhaust all possibilities, remember this: You haven’t.” – Thomas Edison

“All this trouble to learn, when all you have to do is remember.” – the Bhagavad-Gita

“Where there is no vision, the people perish.” – the Bible, Proverbs 28:19

“With our thoughts, we make the world.” – the Buddha.

Demo Room Wrap-Up

Pro-Cache portable LTO-4 offload station from Cache-A.

Inner workings of Spectra Logic T950 LTO-4 robotic tape library.

LTO-4 tape is the archiving format du jour. Portable devices like the Pro-Cache or LTO-4-capable wrangling stations like those from 1Beyond allow tape backup in the field, which makes production bonding companies happier, The tray-loading Spectra Logic robotic libraries offer massive capacities of storage with high spatial efficiency (tapes are stored in trays of eight or ten tapes each; the robot slides a tray out, picks a tape from it, and then slots the tape into a drive).

(A fellow I used to work with came from the tape-storage industry, and he described tape as a WORM system : write once, read maybe1 Still, what else are you going to do that has any better chances of eventual readability, aside from Disney’s successive-color film recordings? Banks and bonding companies like tape; maybe they’re just conservative sticks-in-the-mud, or maybe they know something…)

In a separate suite, Joe Kane (of “A Video Standard” fame, and the more recent Digital Video Essentials test discs) was quietly showing a reference-grade projector he developed with Samsung. It’s a $13,000 DLP system with 10 bit, 4:4:4 capability (not sure if this is via HDMI only or if it has dual-link HD-SDI), 1920×1080 resolution, 85% depth of modulation at the pixel level, and no noticeable geometric or chromatic aberrations. No rocket science, just careful selection and matching of the DLP engine, the lens, and the screen. He says it’s been available for about four years (!) but it seems to be a well-kept secret. The USA distributor is Enders & Associates.

There’s a whole lot more; I only really took pictures of things that worked well in photographs (and once you’ve seen a photo of one double-imaged 3D display, there’s not really much more to see). There’s a complete list of the demos in PDF form if you’re interested in researching things further.

Final Thoughts

3D was everywhere, but no one I spoke to was sure that 3D will stick around this time. Few people are enthusiastic about 3D as a storytelling device… but its ability to get customers into theaters (“bums on seats” in British parlance) is well documented. Time will tell if that continues to be the case after the novelty wears off… or if the desire for 3D really does extend into the home viewing environment.

Last year, the demo room was filled with glasses-free lenticular 3D displays to the same extent as it was with polarized or frame-sequential 3D systems using glasses. This year, no lenticular systems were to be found.

TV loudness issues continue to be a major problem, but at least it looks like both the intent to fix them and the tools to do so are now in evidence.

Panasonic kept fighting off the perception that their new 3D camcorder will be consumer/prosumer kit. Yet when I talked to various Panasonic folks, I was told that the industrial design (looks like an HMC150, even though it has HMC40-derived guts) is intentional. My feeling based on this, and on the tone of Mr. Bergeron’s talk, is that Panasonic is purposefully making the camera look like prosumer gear, all protestations to the contrary aside. That way, they can afford to have it flop, or at least turn out to be too limited (if it looked like a binocular Varicam, the perceived stakes would be much higher). If, on the other hand, the little camcorder is a huge hit, Panasonic can follow it up with a version 2 unit with a fully-pro look and feel (though it’ll still likely use 1/4″ or 1/3″ sensors, just to keep size / weight / depth-of-field / interaxial under control). Just my own speculation, that’s all.

Yuri Neyman’s dynamic range talk on Thursday certainly ruffled a few feathers. There’s been a fair amount of email traffic about it and more than a few grumpy comments. We’re all waiting for Mr. Neyman to post his presentation on the HPA website (sorry, presos are in an attendee-only directory) so we can sift through it and suss why his figures are so radically different from everyone else’s.

As always, the Tech Retreat is great place to learn about issues of the day, and see where things are headed… but if you’re looking for firm answers to settled questions, you’re better off at a trade show like NAB, where the vendors claim to have solved all your problems (grin). The Tech Retreat is like a practically-oriented academic conference: you may not find exact solutions, but you will understand the problems better, and you’ll get your head stuffed full of exciting and thought-provoking ideas.

More:

Recommended reading: Robida, The 20th Century (Robida invented the idea of newscasting, according to one of Mark Schubin’s fiendish quizzes).

16 CFR Part 255 Disclosure

I attended the HPA Tech Retreat on a press pass, which saved me the registration fee. I paid for my own transport, meals, and hotel. The past two years I paid full price for attending the Tech Retreat (it hadn’t occurred to me to ask for a press pass); I feel it was money well spent.

No material connection exists between myself and the Hollywood Post Alliance; aside from the press pass, HPA has not influenced me with any compensation to encourage favorable coverage.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now