When it came time to relaunch the PVC Art of the Frame podcast I thought about how I wanted to contribute. For years I’ve shied away from doing editor interviews because I didn’t want to step on anyone’s toes. While I liked many of those interviews I always felt a lot of them aren’t the world that many of us in editing and post-production inhabit. The new Art of the Frame will give me the chance to sit down and talk to editors working on things that I find interesting and perhaps areas of post we don’t get to talk a lot about. I hope you enjoy them too.

This first interview is with live TV editor Mark Stepp. Mark works in many facets of live TV from rehearsal and preshow, to packages and roll-ins, to fixing mistakes and recutting for different markets. He works on some of the biggest events including the Academy Awards, the Super Bowl halftime show, election coverage, many different music award shows, and much more. We sat down with a couple of beers for a long chat. You can read that chat below or listen to PVC’s Art of the Frame. You can find that here on Anchor.fm and most of your podcast catchers. It’s also available on Spotify, Google Podcasts, PodBean and should be in Apple Podcasts very soon.

Scott S: Welcome to this edition of Art Of The Frame. I’m Scott Simmons here, and I’m sitting down to have a talk with Mark Stepp. So I wanted to have a chat with Mark because he is, I don’t want to say an expert, but he is an expert, but he does a lot of his work, predominantly doing editing and post-production for live television.

And when you think about those productions and editing, many people think, oh, you don’t, what do you edit in live TV? It goes through the air there’s nothing else to do unless, you know, it’s rebroadcast somewhere, but generally, for live television, there’s a lot of work to do. Mark, thanks for joining us.

Mark S: Good to be here, Scott. Thanks for having me.

Mark S: Good to be here, Scott. Thanks for having me.

Scott S: Give us a little bit of a resume background. So people can realize some of the stuff that you’ve worked on.

Mark S: I’ve been editing for more than 20 years. Came into the scene basically when nonlinear editing became a useful tool. Learned nonlinear. Was a little bit involved in linear-based editing at the time, but it was…

Scott S: Oh God, linear editing

Mark S: Exactly, I said the same thing when it was happening and I was ready for that to be done. I’m glad it was gone. Actually learning the trade here in Nashville. And I cut my teeth on music videos, multi-camera concerts, and parlayed that into doing a lot of music, documentaries Behind The Music being one of them that took me to LA a lot.

Scott S: But now that it was traditional post-production where it was shot interviews, transcribed, much different than the world of live TV.

Mark S: Correct. And then as time moved on, I got thrown into making editing nomination packages for live shows. So when you see a live show and they say, “and the nominees for best picture are”, and they play a package that is edited in before it goes live on air.

Scott S: Okay, wait, let’s stop and talk about that for a second. A lot of live programming has a lot of packages and stuff built and shot and edited and completely finished before the show begins that are rolled in. Hence the name I think they call them roll-ins.

Mark S: Playbacks. Prebuilds. Many things like that that can involve a lot of graphics.

Scott S: Gotcha. And we’ll get to that, finish your road into live tv.

Mark S: Okay. I got a conned or sort of thrown into producing bumpers for live television shows. And that is essentially when they say, coming up, Scott Simmons and Mark Stepp we’ll talk to you more on this podcast. I was charged with collecting video of red carpet shots or people mingling around, editing those really quickly, and then getting them into the show.

That was my first time where I started spending a lot of time in a video production truck to see what was going on.

Scott S: And for those that don’t know much about. TV often they bring in very large trucks. Sometimes semi-trucks sometimes huge, highly modified panel trucks. It is literally a TV studio.

Mark S: There are usually 15 or 20 people doing varying jobs inside that truck. And usually, I have myself and an assistant sitting there. Then that started changing. Expanding. And I started getting hired to do what we call pre-edit for a live performance of a show where it’s going to be live live, but they’re rehearsing it.

They record the multi-camera of the rehearsal. And then I sit with the director or producer and artists and we make the best cut of that rehearsal we can. So we have all the cameras they’re going to be the same when they’re live, and we do, what’s called “shot sheeting.” so they know that from two bars are going to be on camera one.

Then they go to camera two or four or seven for two more bars. And we do that a multitude of times working up to the actual live performance. So that when they do the real live performance, everybody involved knows what they’re going to do. Camera guys know their moves, the assistant director knows where they’re going.

The director knows what he’s going to call, and it’s just a way of really practice, practice, practice, and using the technology of editing equipment to help make that work. I will make a timeline. I will put camera numbers in that timeline with the edit and time code. So the AD (assistant director) can go through and exactly to the frame, know exactly what they’re going to do.

I do that for the Super Bowl halftime show, I do it for Oscars performances. I do it for a myriad of things. NBA All-Star games.

Scott S: So, that’s a rehearsal for everybody that can be a rehearsal for the talent. That’s performing rehearsal for the camera. Yup.

Rehearsal for even like the stagehands who have to shuttle people on and off. Obviously rehearsal for the technical director. who’s pushing the buttons when the director calls. So that’s a, that’s a huge part of a making a smooth live show.

If you’ve never seen a live, behind the scenes camera call then check out the legendary call of Cuba Gooding Jr’s Oscar win:

Mark S: It’s a game-changer, honestly.

Scott S: Is this done on all live shows? Is this just the high-end live shows? Because it can’t be cheap to do that.

Mark S: It’s not necessarily as expensive as you would think. Because usually, the technology is already for some reason, I may bring an Avid system in to be doing something else on a show. So the technology’s there, it’s just the labor of an editor that can be there to work.

And then the other people that need to be involved with it assistants or whatever. And lately, I would say in the last five years artists have become aware of this, so they want to be involved in it. And it’s very heavy-handed that they really want to manipulate what’s going on and completely understand it.

So you can spend a lot of time with an artist getting it polished to the shots that they and their management may want.

Scott S: Are there times when the artist doesn’t come in and it’s done with, with stand-ins in a sense?

Mark S: Yeah. There’s a lot of stand-in work that’s going on. And then the artists may even be looking at the stand-in pre-edit to say, “oh, wait a minute.” They may change their choreography based on what they’re seeing. And they may change the direction they want to go, or they may decide I want to make sure we’re on the closeup camera for this line. So then it’s just, it’s really just a form of better communication so that everybody involved, leading up to the actual live live performance knows what’s going to happen.

Scott S: On bigger shows, I mentioned the Oscars and Superbowl halftime show I mean that you don’t get any bigger live things than that, but I think about something like cable, syndicated, live, even like I’ve sort of a pre-taped type of show and we’ll get to pre-tapes in a second. It seems to me that if everyone is there, the gear is set up, that there is no disadvantage to doing that.

Mark S: It’s a win for everybody.

Scott S: So how come that hasn’t been done before? Forever. Maybe it has been done forever, but

Mark S: I would say for me, it’s just really become in the last five to seven years, an excellent tool. It’s almost like I would say just a lot of people don’t know that it can be done.

And then a lot of people and some of it becomes a budget. Some of it becomes time. A lot of times you. Don’t even get a run-through, you know, it’s a soundcheck and do the show.

Scott S: Well, so I was going to say doing that seems like, it could make the show a lot better. I’m sure there are many times when you know how productions if you’re doing a recorded production of delivering a show that is not live, you work often until the very last second, you, you output as you’re watching the clock countdown, on a live show, you have the, almost a luxury of knowing that at 7:00 PM, this show goes live, whether it’s ready or not, it will begin whether it’s ready or not. But in that case, it seems like there are probably times when you just run out of time to do stuff. Is that often planned and it’s just like, sorry, we don’t.

Mark S: I mean, it’s the best-laid plans and you usually have a rehearsal schedule and, ou know, we should have everything done by this. This is the last time it was shot sheet and everything will be set, but then there are always curveballs. But the fact that you’re rehearsing that way. And shot sheeting and prepping and all that way if there is a curveball, it’s a little easier to hit it out of the park when you’re that prepared.

Scott S: Let’s think about that for a second. So good prep work. Good pre-production leads to a much better final result. Is that shocking?

Mark S: And as an editor, I learned very early on to try to go to shoots pre-taped or not try, try to be there to see what’s going on because one I’ll experience what it is their vision is ultimately supposed to be also as an editor, as you well know Scott, we all inherit every problem that happened on set

Scott S: The stink rolls downhill, if you will, it’s usually not the word stink.

Mark S: And if we can be on set as editors and kind of help, like, wait a minute, you know, why is the audio timecode different than the video timecode? You know, for lack of a better example that we can stick our noses in, but we’re also saving the production a ton of money at the end of the day.

Scott S: Are you always invited to, to the rehearsals and all that, or are there times when you say, “Hey, I really need to come here and check things out and do what I do to help the show run better.”

Do you ever get pushback when they don’t want you there?

Mark S: I would say 90% of the time. It’s a given that if they hire me, I’m there for the full deal. From the first frame of rehearsal A lot of times it’s not logistically possible, it’s something that comes up quick, that’s being done somewhere else.

Which, you know, does bring us to the pandemic. We’ve all learned how to work remotely a lot better. And I’ve actually done some of that work in the past year remotely. We all know it has its trappings, but it worked, you know, in the end, just takes more time.

Scott S: But that’s also an extra, you know, an extra person to fly to the shoot, the extra person to put in a hotel.

And I mean, it’s only one person, I guess unless you have an assistant with you, but it just feels like with, you know, with production in general, when you consult post early on you’re, you’re just setting yourself up for more success.

Mark S: Yeah. And if you look at the grand scheme of things of how much money is being spent on a quote “live performance.”

Scott S: Especially the big ones.

Mark S: Especially the big ones, but really any of them, even down to, you know, somebody was going to spend a hundred thousand dollars on something. Why not spend an extra five grand to bring in the editor. He probably will bring his gear and say, “let me help you out on set.” And it’ll save you 25% of your post time.

Scott S: So what else does an editor do for live television? That can’t be all.

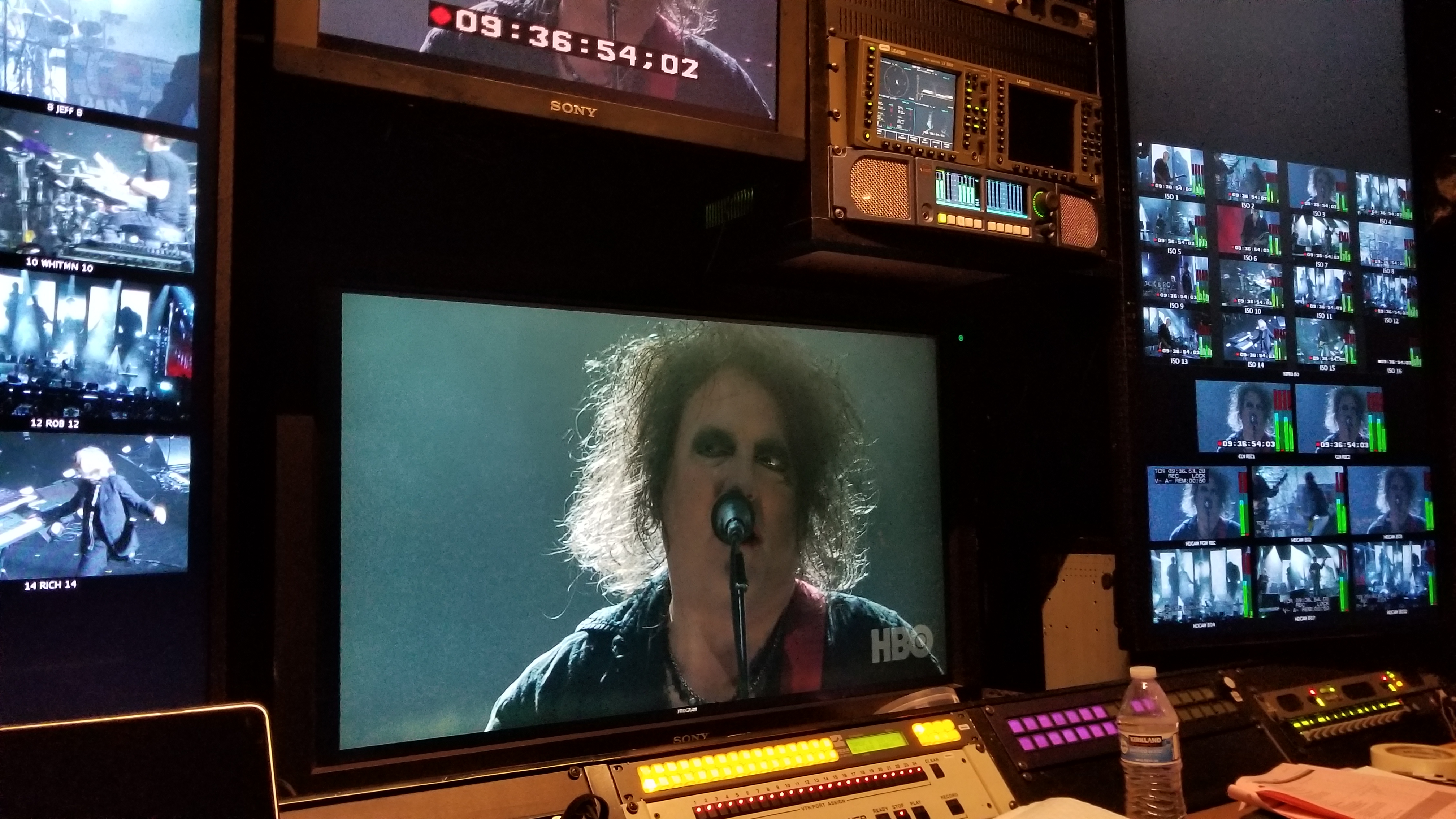

Mark S: No, it’s not at all. There’s a lot of different things that go on. And I’m sure other live editors are doing different things than that I’m doing. But again, with the advent of technology a great company called Pronology came up with a system called mRes that allows you to record multi-camera feeds as many as you want directly into an Avid shared storage media system. And basically, the way that works is as soon as they start recording, let’s say it’s 12 cameras. Those 12 streams are being recorded. And about 30 seconds into that, you can make a multicamera group and start editing. And yes, this is a live show, but in the states, we have three different time zones.

And if I’m doing a show in New York, And they want it went on at 9:00 PM in New York and there was a flub up. Then they may want to make some fixes for the west coast feed. Yes. Technically it’s not live anymore, but we’re all trying to put our best foot forward and make it as good as we can.

So we will extremely quickly make the fixes that a producer or director wants and re-output that act and ship it to the network and then they will play it back as part of the west coast feed. So usually it’s about an hour, hour, and a half window to get that done. So we were doing these fixes as the show goes.

Scott S: Most west coast time, Pacific time zone, is not live correct? I guess sometimes the air it just airs a lot earlier,.

Mark S: It goes a lot earlier there. And if it’s a live west coast show, you can do the same thing. You’re just technically in a different time zone doing that. And that’s a tool that was really used a lot when it first started being able to do a lot of people aren’t doing as much as it could. The top of the bar has gone down a little bit with pandemic and mostly it’s things like somebody fell or camera’s in a shot, or, you know, there, there was heavy-duty choreography and somebody went the wrong way. So they’ll want to fix that if they can.

The other thing that happens is a disaster happened, something really bad happened during the show, the live live show and for the west coast, we have to take the last dress rehearsal and insert footage from that, into that show.

Scott S: Is that ever a place where you would take an entire dress rehearsal? Because I guess being a dress rehearsal, they’re wearing the same stuff. It’s filmed just like or recorded. It’s not really filmed, but we use the word film just like a live, just like it was the live show

Mark S: That happened actually to me once in a major way I was doing the live version of Rent – The Musical couple of years ago for Fox. I believe it was. And the night before the show day, the lead actor fell and broke his leg.

Scott S: That can be a problem on a live theater production.

Mark S: It was a heartbreaking thing for everybody because it was a great show and everybody was ready to do it. It had an unbelievable talent list and the quality was really good.

It happened in the middle of the night. I didn’t, I didn’t realize it until they called me on my way in to do my normal show day work. They said, Hey, here’s what’s happened. So I sat down and piecemealed together. Different takes and acts and shots from three different dress rehearsals.

Wow. Those were completely full-dress rehearsals. And that was the day of the broadcast. And that became the broadcast master.

Scott S: So how many cameras was that? Do you remember?

Mark S: Oh gosh. You’re really only dealing with three to eight cameras at a time, but there are different sets, right?

Scott S: Yeah. Well, even like, let’s say it was five cameras, times three dress rehearsals. You’ve got, you know, 15 angles at any given point, but you, that is a lot of eyeballing going back to all right. Here’s the song. 29 seconds in. Right.

Mark S: Which takes us back to all those dress rehearsals that were shot sheeted because they were being used as tools for the live live show.

Scott S: So we already had great notes and, and everybody knew that this performance from take two, was the keeper.

Oh, that’s great.

Mark S: The challenge was stitching together scene-to-scene from, take-to-take. If, if there was like a lull or something, we just had to pull it up. And then we were also trying to deliver our show to time.

Scott S: Did that happen to the whole rent show or was it just the parts where that particular actor was in it?

Mark S: The entire Rent show played and what they did the great thing the great outcome of it was, there was a live audience. So the troop, the talent performed the show as a standup, they didn’t move, they didn’t do any choreography. They played on one set and they just performed all the music. At the same time, we were playing back the tape of the show and then the very last act, which was really just an epilogue and credits, that went live live.

Scott S: Is this known information?

Mark S: Yes, it was, it was, there was an announcement made before, before it, and there was an announcement, a slate at the top of at the beginning of the show saying previous recorded.

We had an, you know, and explaining what was going on. And then during that last act, the guy was sitting there in his wheelchair and he talked about. It was, it was a great outcome in the end that the, the way the executive producers and the network handled it. Yeah. It was a very adrenaline-pushing day.

Scott S: I assume he had an understudy like Broadway does, and they could have popped him in, but.

Mark S: The key thing you just said was like Broadway does.

Scott S: Yeah. I said the word assume, which has all

Mark S: Since then all those TV musicals do have understudies. But it, it, it worked out great in the end if the biggest thing was that people didn’t get to do their real live live show.

So in a very long way that answers that.

This live switch isn’t as exciting as the Oscars but it’s still a good look at process of calling a live shoot:

Scott S: That’s a great story. So other stuff that the editor does before the “live” first minute of the live show drops, what else do you gotta do?

Mark S: I do a lot of QCing of things that come in, especially with the pandemic.

There’s a lot of remote delivery people that have shot stuff at home on their iPhones, and they’ll get those last minute. So I’ll take them into an Avid and color grade them a little bit, level out the audio. Make them a little bit more reasonable for television broadcast standards had to really take a hit when the pandemic hit. This is true and now that’s a whole different discussion.

Scott S: Pre pandemic times though, you were still I guess they’re often ENG crews that were outshooting stuff. Sure. You know, they could, they could be actually like more narrative dramatical things. They could be out doing “man on the streets”.

There’s probably any number of things to depending on the kind of live show it was that fit the show.

Mark S: There’s a myriad of things that go on and it, and it all comes down to what the creative direction becomes or what their vision they have is going to be what technology is available and then how we can best exploit it.

I use a device a lot on bumpers and playback called an EVS machine, which was originally designed to be a sports playback machine. And that’s what it’s used for. It’s a very simple little device, 8 buttons, and a wheel, and a joystick, and we use it. We manipulate it to make all our bumpers and to marry graphics and, you know, cheat a lot of things into a live show that” isn’t necessarily live”, but they are a part of the live broadcast.

Scott S: The EVS has been around for a long time. I hear that term a lot.

Mark S: A long time. And it’s a very stable tool and it’s another device that you can manipulate how many channels are recording with it, based on how many channels you want to playback. And as soon as you’re recording, you start playback.

Scott S: Let’s talk about the editing for a minute. A live show is pretty much a multicam kind of show. Whether you’re talking about a music show, an awards show, the Rent type of thing. What type of multicam editing sort of skills does someone need to have? If they’re going to try to get into the post-production side of live television.

You’re not editing it on the fly. That’s being called by the director. We’ve talked about the rehearsals and all that, but you’ve got to know a lot about the technical side of multicam. As far as the cameras, timecode, how everything syncs together, you have to know about how to work with that in the editing system and Avid predominantly what you were, I think pretty much all of the work on how what is the multicam knowledge?

Mark S: You hit the big, broad stroke of it is that it is equal, left brain, right? You really got to understand the technology and understand why time code is time code, what your audio assignments are, where things are going, your ingest rates, your digitize rates, how much storage you got, how hard you can push the bandwidth of your system.

You know, are you using 10 gig switches, two gig switches, one gig switches? How many people need to share this media at the same time? So there’s a lot of technology involved basically to understand your limits. Okay. And then the creative part on it of understanding that, oh, I just saw a camera in a shot. I know that needs to be fixed instead of the time that you wait for someone to tell you that there’s a fix can be minutes and you’ve already lost minutes. Right. You know, you’ve lost a lot of time. And so the clients I work with consistently, that’s part of the reason they hire me, that I understand their eyes and understand their tolerances so that if there are fixes to be done, then I know what they want.

A lot of times too, an artist will hire me because they want my touch on the shot sheeting and the prep and all that because I’ve worked with them before say a multi-camera concert in the past. Then also a lot of these shows they go live live, and they’re done. And then we do a post edit.

For what they call the evergreen version that will sit on shelves and be the archive version it might be a repeat version two weeks down the road, or they may sell internationally. And the big thing on those is as you probably well know, once a production is over the production side of people, they’re off on the next one.

Right. And so if a show like that moves in the post, I’m kind of left you know, just doing it myself. And there’s a lot of trust in there. I can send QuickTimes and people can approve stuff and nothing’s going to go out the door until they see it. But at the same time, they don’t have to be there every minute.

You know, basically like you would a normal edit session with producers sitting there calling every shot.

Scott S: We went from the pre-production side before live happened to what you do after sometimes let’s, let’s move into when the countdown happens and the show goes live.

What, what are you just sitting there? Obviously, you’re not, we just talked about, you’re looking for problems, but are you, do you have a notepad out? Are you watching all the ISOs, all the camera feeds on a monitor, or what?

Mark S: In a perfect world, you hope to be doing nothing, but it never ends up that way.

A lot of times, you’re still waiting on stuff to come in. So somebody might be shooting something for act eight and you’re in the middle of act two.

Scott S: Well, let’s back that up for a second. So it’s a live show. It could be two hours, probably three hours on a big award show that maybe runs over. It starts at 7:00 PM on central time, which is where I am.

And there’s something that has to be in the show at 9:00 that has not been finished yet they may be still rolling the camera. So what are you going to do a quick edit is this stuff is it a one-shot or what type of thing could that be?

Mark S: It’s it, it can be a variety of things. It’s usually pretty simple stuff because at that point, you don’t want to take the risk of broadcasting, something that’s extremely flawed, and no matter what, we still want to have time to do our work on it. QC it, get it into the playback system, and let them QC it too. And all of, most of all of that work has to take place during commercial breaks because everybody’s working during the actual show.

Scott S: So these can’t be really long packages or really long segments they have to and I think everybody, as part of live television, you have to know your limitations. Yes.

Mark S: And generally I work with a bunch of people who are adamant about stating that we are out of time. You know, we, we can’t push this any further

Scott S: I can think of live shows, which I have seen, and maybe have worked a little bit on when people didn’t say they were out of time.

And what went to air was horribly flawed, fixed later, fixed for the west coast feed. But you do only have so much, a finite amount of time, but I think you, you mentioned you have to get the footage, you have to ingest it somehow some way, perhaps do a little bit of edit. You have to QC it, quality check it, it has to be then transferred from your editing system, into the truck for the broadcast.

And then someone in the truck also has to QC it. Is that why would they QC after you QC? Is there a worry that the transmission from edit suite to truck could bring in artifacts?

Mark S: That could happen, but I would say 90% of it is another set of eyes. Okay. Now, usually, I have an assistant or other editors around me and if I do that, I’m going to have them look at what work I did too.

Just like I would look at what work they were doing too. Right. We don’t want any of our work to leave the edit bays flawed with a mistake on it. Because then it could get past the next person in line and in the truck, the same goes for them. They’re the ones playing it back.

If it’s flawed, they’re going to get the wrath and none of us want that. And in the live show scenario, If a playback package goes wrong, that’s the worst nightmare for executives.

Scott S: I was going to ask, what about, we talked about the situation that happened with Rent the actor breaking the leg and the audible they had to call. What would happen if you had this package in the live show that could not get done and the machine crashed? There’s any number of things that could happen to make the package not get done is the rest of the show pulled up? Do they have a contingency plan for how to fill that three minutes?

Does there’s a comedian come out and I mean, there’s, there’s gotta be, it has to have happened?.

Mark S: Yeah, it’s definitely happened. I’ve experienced it. Most shows end up being a little long anyway. So let’s just use an example that for some reason an awards package, was 45 seconds long. Didn’t make it, the immediate thing was, well we’re two minutes over anyway, so we’re okay. Or these shows are usually hosted so they can get to a bit and have a host egg it on a little bit.

Scott S: Yep. And I’ve probably seen that happen and didn’t realize what the host was doing.

Mark S: I remember doing a comedy award show one time and Judd Apatow was hosting and, and they were going to be short and he just blatantly came out and said, okay, we’re short. I have to fill. So he started telling jokes and that’s fine for a show like that. An elegant show, like the Grammys or Emmys or Oscars, they don’t want to have that kind of image about them.

So they’re trying to use smoke and mirrors and a way to cover that up. It’s usually when that happens, it’s a technology problem. A lot can go wrong. And technology is either on or off it, it either works or it doesn’t generally would, would hope that it works.

I did a concert for the Super Bowl one time and we had pre-taped part of the show.

And then part of the show was going to be live. One of the phases of the power on the truck froze up.

Scott S: Ooh, it sounds like some somethings you could never, I mean, sure, you plan for problems, but something like that is not your normal issue.

Mark S: Third of the power in the truck went out. Luckily for me, I had an edit bay station set up away from the truck.

So a long story short, we manipulated the order of the show to make it work to where the show kind of still came off without a hitch. But it did require a guy with a can of Freon spraying one of the phases of the power for the entire show while making it ice over so it wouldn’t cook.

Scott S: So there’s your technical issues beyond just the hard drive crashed or, I had to reboot the computer or even like the SD card or the P2 cards, remember those, came out would not mount. That’s like a whole other level of, but I guess when you have a live show like that with these trucks, you have some very, very talented and very smart engineers there who are making all of this stuff work together.

Mark S: Right. And the way it generally works is the trucks are manned by consistent engineers show to show. They know the truck inside and out, and as you develop a relationship with them, they know how you’re working inside and out. So a lot of the times I show up to shows and everything I need is already there. It’s already laid out because the guy did the last show with me, or he knows me, or, or they’ll email or call and we’ll talk tech.

You know, I had two emails and a phone conversation. The tech guy for the show I’m in Nashville for right now, before I start tomorrow. And so you hope that all that gets ironed out before you start, but you really, really depend on their talent and their skill, especially when things go wrong.

Scott S: For something like live TV, especially big-time live TV it’s really kind of a small pool. It’s not as huge of a niche of our world I think as people would think, and if you don’t perform or if you mess up a couple of times, you’re probably kind of out of that call pool, because you can’t, you can’t be trusted, but you can’t be trusted to do what you need to do to have the live show happen.

Mark S: Correct. I work with about the same 60 people year-round, and we work all over the country and different parts of the world and, and I’m relieved when I see them. But it’s very competitive and it’s also can be extremely pressure-driven. So if people get burnt out on it then they may take off or there are very few opportunities to make big mistakes, it’s a lot of money at stake, you know, advertising-wise and network dollar-wise. So they’re not, they’re not going to tolerate much of it, but at the same time, it’s also a big team effort. No one points, fingers and says, “why did you mess that up?” A lot of figuring out what happened will happen, but, you’re going to see the same thing again, so you don’t want it to happen again.

And your chances are you’re going to work with the same people again. So you want to make it work.

Scott S: We talked about if there’s a problem and say a segment, doesn’t go into the show, which would make the show short. What happens when the show runs long? Oscars are famous for running long, but I think about you know, little things like the Grammys years ago, I never forget I was watching it was a Billy Joel performance.

The song was River of Dreams and there’s like a pause right in the song. And when it happened live, he paused, he stopped playing. He turned around and looked at the camera. He said something like we’re now wasting valuable advertising time that he just let this pause, it wasn’t super long, but you know, something like that, that happens.

Or you a renegade artist who just doesn’t get off the stage when they’re supposed to. That’s not unusual.

Mark S: You got to love Billy Joel for that. Well basically, yeah. What they usually do is they build in what they call it Velcro and, into the show, rundowns and Velcro is items that can stick, or it can easily be unstuck.

Uh, One way that we do it, which is part of the pre-build editing is you will make, as the show goes into the second hour and third hour, you will make alternate versions of nominee packages. You’ll have a long version. That’s let’s say a minute and a half, then you’ll have a medium version that let’s say is a minute and then you’ll have a short version.

That’s 30 seconds. Okay. So at the end of every act, there’s what we call there’s a back timer working that shows you when you gotta be off the air and he’s counting down all the elements and the executive producers, the really good ones. There are only a few of them left who are constantly looking at that and going we’re right on time at the end of every act. Kanye got up there and talked forever. Now we’re long.

Scott S: Poor Taylor.

Mark S: Yeah, poor Taylor.

Scott S: For the record. I think Taylor has the last laugh in that one anyway.

Mark S: They’ll say okay for this next act, we’re playing short packages. . So if there were three packaged, and they went from a minute and a half packages down to 30, they bought two and a half minutes back or a little bit more. And that way they’re constantly trying to Velcro the timeline. Let’s say to make it breathe or not breathe. It’s how they go.

Scott S: Almost like a sliding and sliding scale. And I think that also sort of goes to, I don’t think anybody who’s ever watched a good live show they know there’s lots of pre-production work that goes in. But I think the amount of just little things like that is something that you probably never, you know, most people I’m like, I never think about that when I’m watching the live show.

Mark S: And the Oscars is an exception because they don’t care. They just, they just go on.

Scott S: But there

there’s some lesser-known award shows that have to be out, have to be done at the bottom of the hour.

Mark S: The thing that you’re, you’re running up against affiliate news programming.

Scott S: And they don’t like that to be preempted.

Mark S: Bingo. They don’t, you got to have their news go on at 11 o’clock or 10 o’clock, whatever it’s supposed to be. So that’s a big deal and the really good showrunners, executive producers take pride in delivering on time. I mean, it’s, it’s kind of a, a really cool thing to be able to. And, and at the end of it, if you do it ever, everybody involved top to bottom feels like they’ve accomplished something well because it’s kind of the icing on the cake. We didn’t go long, we weren’t short.

One thing I do during shows is as the show is going I or somebody else working on the show has time, we build a highlight package of what’s happened during the show. And that plays during the credits.

Scott S: Is this before we get into how you build it, are you just making markers in, in the Avid as that footage is loaded in do you have a notepad with the screen with time code on it?

Mark S: I’ve done it both ways. If I am actually recording into the Avid, then I’ve got one hand on it and I’m on the line cut, and I hit a locator when I see something good. Okay.

Scott S: I think they’re called “markers” now in Avid old guy.

Mark S: I’m sorry, markers. So then when I get time, Or if there’s an assistant around, then they’ll go through and just sub clip out.

Usually, I do this in an EVS because the EVS will playback in slow-mo and still look good. And also that slow-mo is rampable. Really good EVS operators we’re back timing to the end of the show, and we know we want this magical, last shot that’s the fireworks or whatever. Then we’ll get to that. And we still need five seconds, but we only got a three-second shot.

You can slow that down to make it last five seconds.

Scott S: That’s interesting because I’m sure all of us have watched, especially musical shows that when they end, you do see the credit roll with a lot of these slow-mo shots, but yet during the show itself, they’re not rolling slow-mo and they don’t have a, you know, contrary to like, what’d you see on the like the Super Bowl and a lot of these sporting events now where they’ve got the shallow depth of field cameras out there, or they’ve got those super slow-mo cameras that they can do replays on.

You’re not recording the entire show with the ability to just slow-mo it down with slow-mo cameras you’re using the EVS to do that.

Mark S: Yeah. Correct. And it’s very smooth and it’s highly flexible on the speed. And usually what will happen is I’ll do this all during the show. We’ll pick out all these shots and we’ll line them up, and I’d like to make it linear order because it was how the show happened.

The executives will call into me and say, “Hey, you know, how long can you make the highlight reel? We’re running a little short.” And I’ll usually say, “well, how long do you want it?” And no matter what they say, I’ll make it 30 seconds longer. I’ve never done one that’s longer than two and a half minutes. So I’ve made it three and a half, three minutes roll-out reel.

But that’s another piece of Velcro, right? That if all of a sudden they catch up that same three-minute rollout reel can be made into 30 seconds. We can just start taking shots out. Like I’ll go through it real quick and go kill it, kill, kill, kill it. And then keep the big hero ones and then playback.

And then it doesn’t need to playback in slow-mo.

Scott S: Is that a place where they can, I guess they can stretch the actual credits themselves to fit whatever they need to be?

Mark S: Yeah. Or they just start them later because there’s a lot of legality issues. Like, you know, directors have to be two seconds and then they get everybody else.

They get a frame or less thing or less. So it’s usually just a cue of when they’re, they’re all trying to get to that production logo at the right time. So, and, and our team helps them get there.

Scott S: So what happens when the show is done? So let’s. It came on at seven and went live and you, and you’re on time and at 10:00 PM the credits roll you get the final logo the live show is into the transmission is ended. What do you do? What’s your next hour?

Mark S: The first five minutes are waiting to see if there are any additional fixes.

Scott S: For the most part, as the show has been going along, if there are problems, you see them, someone else sees them, there are notes made of here’s everything we have to fix.

Mark S: Right. Sometimes there could be a problem that wasn’t had anything to do with our end. It could have been a transmission problem, satellite blip, or something. So the network may want us to feed another act,” Hey, act three had a hit? Can you guys refeed it and check this time code?” So we check the time code.

Everything’s good. And then we just play it back and you have to play the whole act back. You can’t just play a fix. That’s the one, one trapping of it that requires audio, A1 engineer to stay on board, AD, TD, playback there are about eight or nine people that have to stay. And then you have to make sure they don’t start pulling the power.

Scott S: Oh, that would be bad everywhere. Let’s talk about that for a second. We live in a day and age, when you can take a finished MXF file, a Quicktime, whatever, and you can insert a piece right into it. So you don’t have to re-export your entire hour-long program. Why do you have to feed an entire act when there exists a file of that?

Why can’t you just insert a fix?

Mark S: Two reasons. One is if you play it back live, they can QC on their end while it’s going live. While it’s playing back. They don’t have to take the file and then play the file and then play it back again.

Scott S: So they’ve been QCing it as it’s being transmitted.

Mark S: Correct.

Also, you have to redo all the closed captions because the closed captions were live. So the closed caption artist has to sit there and do the closed captioning again. So that’s why that’s done and believe me, I, when I first got exposed to it, I go, why can’t I just upload a QuickTime again, it’s not the present workflow.

Scott S: Gotcha. Yeah. So that first five minutes you’re getting any new fixes,

Mark S: Just making sure you’re getting the all-clear and there’s a, there’s a head person in the truck that’s in charge of transmission and that person is the last to say that, “okay. We’re clear.” Because then they’re going to unplug the satellite and they’re going to start pulling power.

Scott S: So after that five minutes, didn’t you immediately start working on the fixes

Mark S: If there are any yea.

And that would be usually for the west coast feed of things in the US or if there’s an evergreen version, that they know they want to fix one thing and we’ll just do it while we’re there.

Scott S: As opposed to coming back the next day, you’re taking it back to the edit suite.

And again, you have to do extensive fixes for an evergreen, or I guess, foreign distribution or something like that. There are times when you can wait.

Mark S: Which is another great thing about having, you know, whatever editing systems you’re using them and their shared storage onset is because if you’ve recorded it all, you could unplug it, take it back to your edit bay, and plug it in and start right then. So if the show ended at 10 and you needed to turn around a show by the next morning, you could be editing by midnight easily. So there are eight hours. You can plow away. Yeah, there’s a lot of coffee involved a lot of cursing.

Scott S: I think that’s one thing, your service services, and when I’ve worked with you before it’s is turnkey and it’s like, I will arrive with my stuff set up. You obviously don’t have the EVS, you don’t have the truck, you don’t have the other system we talked about, but you know, those exist, but you can set up your post-production facility onsite and provide that service.

Yeah. You can provide the fixes you provide they evergreen, if need be, then you tear it down end of the night, put it back in your truck, take it back to your place and you can set back up and go back to work again.

I’m guessing there are probably a lot of just you know, editors who work on live TV, they’re just bodies for hire that could walk in, sit down, and do their thing. Then walk away at the end of the night, right? That’s two entirely different even skillsets. You have to be able to, you gotta be extra technical when you sort of provide the turnkey. Right.

Mark S: Yeah. And I do some of both. I prefer to do the turnkey because if I arrive plug and play, I know my gear has been tweaked out.

Scott S: And you can charge more.

Mark S: A little bit, but you,

Scott S: but you have overhead, like, and that’s not just charging more to make more money. You have a lot of overhead you have to pay for, you have to insure, you have to upkeep

Mark S: upgrading is a constant financial battle. And then I do shows where, you know, because of location or whatever, or the group of people, I’m just another person that’s there.

And, and I’m happy to fit in. The turnkey thing has worked out well for me because people that hire me have trust that I will arrive with the right equipment and that here’s my plug, let’s QC it, and it’s minimal, the hassle of everything’s okay, let’s go. And as you well know, I try to work very quickly because I don’t want to be there all night, so I want to get in and get out.

And that saves everybody money.

Scott S: Yeah, for sure. For sure.

So the last question I have about this, it’s probably one of the most important ones and we, haven’t even touched on it yet. As you know, in a live production I’m using air quotes for production we think about people running cameras. You think about all the people on the set, all the people inside around the stage.

You’re thinking about the producers.

Mark S: The COVID testers.

Scott S: You’re not thinking about editors and post-production, but that’s an important part of it. But here’s the question I have, even though you are not as an editor as a “post person” you’re not in and around the production side of things,

Are the editors able to utilize craft services and catering?

Mark S: Yes.

Scott S: Okay, good.

Mark S: Actually extensively because you’re not as on a tight schedule as everyone else’s and if you’re lucky enough that they’ve kind of built you a place, you have your own trailer, you can con craft services into setting up your own craft service station. So, you know, you don’t even have to stand up.

Scott S: That is next-level stuff right there.

Mark S: That’s the best question of the day.

Scott S: I hope that people, this helps people. If you don’t know a lot about live TV, I hope this kind of gives you an insight into what it takes as far as the post-production side of things. Because I, you know, I was an editor for years before I did any sort of live-focused stuff.

And did not realize how much went into it from a post-production same standpoint.

Mark S: Same here.

Scott S: Is there any, any, like things I missed any like weird little things that you know that you have to do that no one ever?.

Mark S: No, it’s just for me, it’s you know, left brain, right brain, understand the technology and understand the changes in technology.

I kind of try to keep up with that. I don’t necessarily enjoy it, but that’s a must. That side of the business. And that definitely relates to being a turnkey provider.

Scott S: Yeah. There are so many editors that become computer nerds by default. Not that we ever wanted to be.

Mark S: And as nuts and bolts editing goes, speed and accuracy is the most important thing.

And also understanding what the executives or the director wants. It’s not a, “we’re going to mess around with this for hours to find the magic moment,” it’s “this is what we want this to do” doesn’t mean you can’t offer a better idea, but you are dealing with a deadline, right. You’re constantly dealing with the deadline and that is first and foremost in everybody’s mind.

And then, you know, willingness to travel. So, I mean, it took me on the road big time when I started doing it.

Scott S: Well, live shows don’t always happen in the same place.

Mark S: They have for a year, but now they’re not anymore.

Scott S: Getting back to normal.

Mark S: Can I plug? Okay. Well, if anyone has any questions about any of this, you can reach me at info @ uppercutmedia.com or stepp.uppercut @ gmail.com.

Scott S: Yeah, the normal questions, like where do people find you, but you’re not on Twitter. Or on Instagram or, Tik-Tok or whatever, whatever.

Mark S: Yeah. I am scared.

Scott S: There you go. There you go. Or shoot me a message because I can, I can relay it on to Mark. So thanks for chatting with us about live post-production in live TV.

Mark S: Yeah. Thanks, Scott.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now