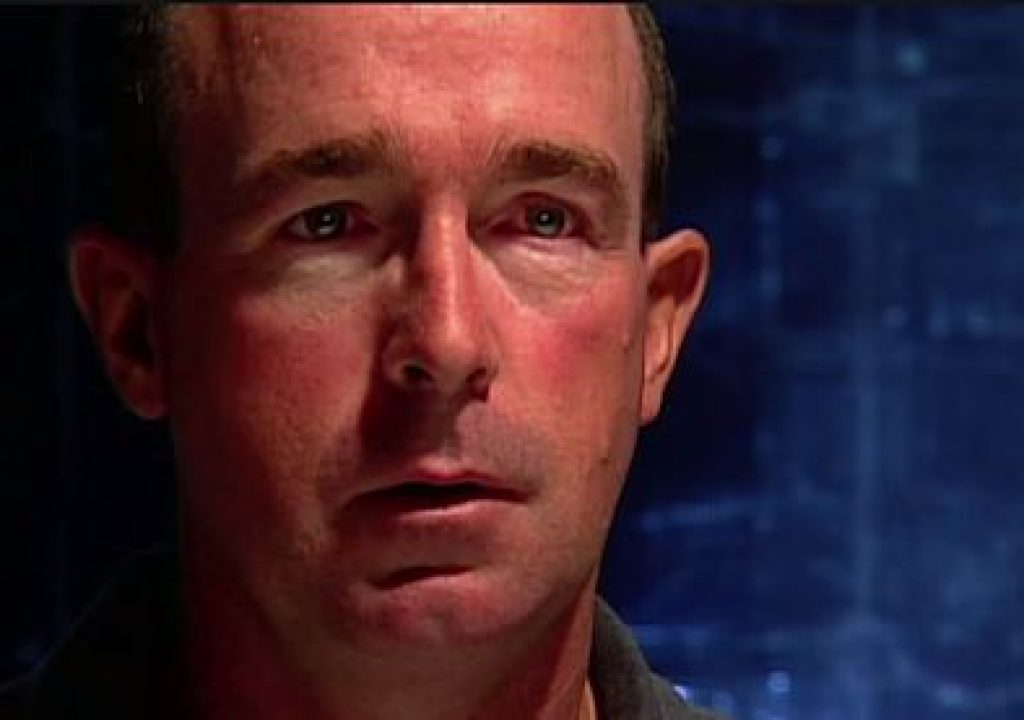

A sign taped to the door says “Quiet– filming.” This only makes you more nervous. You enter the room: it’s mostly pitch black, except for the brightly lit chair in the middle.

A very friendly stranger, silhouetted in the dark, is shaking your hand with inappropriate enthusiasm. Another shadowy person looks you up and down and then rushes to adjust lighting equipment. Everyone is saying “just relax.” The more they say this, the less relaxed you are.

Welcome to your interview. Just relax.

This is how you might feel if you were being interviewed for a documentary, corporate video or commercial. Fortunately for you, you are probably one of the people on the other side, standing in the dark: a producer/director or DP, perhaps.

You’ve seen what you want in other people’s movies: honest, insightful comments made by clear-eyed people who seem, quite naturally, to support the essential story of the film. If you are about to ask the interview questions, you may look at the distrustful, distraught subject who just walked in the door and panic: how can I get a good interview from this person?

Just do what I tell you to do and you’ll be fine

The problem is that people in movies speak concisely and effectively. People seldom do this in real life. Good friends may be able to chat excitedly and informatively. Strangers: not so much. The interviewer is usually not a character in the movie: the interview subjects should appear to be speaking extemporaneously, un-prompted, to an unspecified, unheard listener. Interview time is usually limited by the subject’s availability and by the production budget. Organizations normally want interviews to convey carefully researched, edited and vetted information that has been honed into position statements.

The problem is that people in movies speak concisely and effectively. People seldom do this in real life. Good friends may be able to chat excitedly and informatively. Strangers: not so much. The interviewer is usually not a character in the movie: the interview subjects should appear to be speaking extemporaneously, un-prompted, to an unspecified, unheard listener. Interview time is usually limited by the subject’s availability and by the production budget. Organizations normally want interviews to convey carefully researched, edited and vetted information that has been honed into position statements.

You could have instructed the subject to come prepared with rehearsed answers. When the person arrives for the interview, you could give him or her a list of rules and behaviors to help solve your problems:

- put my question in your answer

- use complete sentences

- don’t look at the camera

- be concise

- don’t say “like I said before”

- use the name of your organization instead of “we”

and so on.

You could interrupt the subject to correct his or her language and enforce the rules.

You could then rely on B-roll (cut-aways to other footage) to cover the inevitable editing of the person’s sentences to construct better phrases.

In my experience, this is how most people do it. I keep a database of details about my jobs (if you’ve worked with me, you’re probably in it). It has about 1,200 productions in it. Of the 400 interviewers I’ve worked with, about 390 have solved the problems of interviewing this way.

The problem with this prevalent method is that is it pretty difficult for everyone involved. If the interview subject hasn’t had extensive media training (as most CEOs and politicians have), all of these rules, all of this focus on stage craft tends to confuse and terrify him or her. As a result, the subjects tend to have the life squeezed out of them. This is less like filmmaking and more like taxidermy.

The problem with this prevalent method is that is it pretty difficult for everyone involved. If the interview subject hasn’t had extensive media training (as most CEOs and politicians have), all of these rules, all of this focus on stage craft tends to confuse and terrify him or her. As a result, the subjects tend to have the life squeezed out of them. This is less like filmmaking and more like taxidermy.

Many directors, through amazing skill and/or force of will, can make great movies this way. However, I’ve learned a much more reliable, much easier method from the ten exceptional documentary filmmakers that I’ve worked with.

Here’s how they do it.

Start at the beginning

Movies are great at moving people, at bypassing their rational brains, influencing their beliefs and motivating them to action. Movies are temporal: one moment leads to the next, taking the viewer on a journey, perhaps an adventure. Movies tell stories.

Data, on the other hand, isn’t a movie’s strongest suit. It is not, in itself, a good story.

Data:

- is atemporal: a fact is always a fact

- is an essential element of a rational argument

- works best in PowerPoint presentations

- or bullet-pointed lists

Interviews work best in movie projects conceived more as stories and less as presentations of data. A movie is best if it is about the passions of customers for a product, partisans for a cause or participants for an event. Data about the product, cause or event is of little interest to a movie audience outside of this context.

Convince the clients that if they want to improve on PowerPoint slides then they have to use movies for what movies do that slides can’t: move people. Movies aren’t reasonable. In fact, the last thing you want a movie to do is invite the audience to think of rebuttals to your arguments.

Write the script or screenplay such that data is handled primarily in titles or voice-overs. This frees the interview subjects to focus on their passion, enthusiasm and experiences. This also features the data where the client can see it: in plain text in the script. This helps them relax and lets you focus the interviews on storytelling.

The reason for B-roll is to cover sound edits and hide your interview problems. However, it tends to flatten the story into two dimensions: we’re talking about something; oops, go look at this somewhat related thing while I fix a little problem. OK, we’re back!

The reason for B-roll is to cover sound edits and hide your interview problems. However, it tends to flatten the story into two dimensions: we’re talking about something; oops, go look at this somewhat related thing while I fix a little problem. OK, we’re back!

When you cut away, why not cut instead to a parallel story, one that enriches, complements and expands the main story? The writer can design this story while designing the main story, so that they work together. This isn’t B-roll anymore: it is more of the story. It takes some of the storytelling chores away from the interviews. Cleverly done, it can lessen the requirement for precision in the interviews, making them easier to do.

Select well-spoken interview subjects who are passionate and knowledgeable about the topic, if possible. When scheduling the shoot, leave plenty of time to both setup and shoot the interview. Most subjects aren’t trained birds who can squawk on command: allow enough time to talk with them.

Send the interview subject these instructions in preparation for the shoot:

- we’re going to talk about [general characterization]

- don’t prepare answers; we’ll just have a conversation

- don’t wear herringbones or white or green/blue (if shooting for green/blue screen compositing)

- we’ll powder your nose, bring your own if you prefer it

Getting the interviewee, charged with conveying the company line, to show up rested and un-rehearsed is the hardest part of doing corporate interviews. Start gaining the company’s trust as early as possible. Good luck.

The day of

The interviewee has just walked into the room. Reassure him or her with these promises:

- we’re talking to you because you are the perfect person to [talk about the subject]

- we edit the interview

- whatever doesn’t work, we won’t use

- we are experts at making you look and sound great

That’s it. No rules.

Have the room ready to shoot: changing the room lighting after the subject enters can feel like sealing the gas chamber. I try to have the door that the person entered positioned behind him or her during the interview: having the camera and crew blocking the potential exit can increase desperation.

The interviewer should immediately sit down in his or her interview chair, invite the interviewee into the hot seat and begin small-talking. The rest of the crew can do no work to prepare until this happens. While these two chat, the camera people frame up, focus and fix problems with the background. The lighting people adjust the light, sound people adjust mics and levels, makeup people apply powder.

DPs:

Make each subject look his or her best. Quickly adjust for each person before the interview starts. Be ready for quick tweaks so the interview doesn’t have to be stopped once it starts.

Good answers are more important than most tweaks. Make the set work for the sound department: use their sound blankets in your lighting plan as negative or positive fill. Keep your mouth shut as much as possible; let the interviewee focus on the director.

Producers, directors and interviewers:

People who are sitting and listening to you (or looking at notes or drinking water) look and sound different than people who are talking. Once the interview begins in earnest, they can lean past the microphone or turn their heads away from the light or start to sweat or change in a number of ways that can ruin the interview for sound or picture. When the crew moves stealthily and skillfully to tweak these things during your off-screen questions, thus saving your movie for you, do not freak out. Remain calm and carry on with the interview.

The most important tip

OK, I realize that I lost most of you eight paragraphs ago when I advised against giving interview subjects any rules. How can you get them to speak in complete sentences? How can you get them to put the question in the answer and make eye contact and not say “um” and use the full name of the organization if you don’t give them rules?

Here’s how: don’t ask the interview subject any questions.

If you ask me “what color are your eyes?” I’ll probably reply “blue, mostly.” If you cut to a shot of me saying “blue, mostly” the audience will have no idea what either of us is talking about. On the other hand, if you say “tell me about your eye color” I’ll most likely say “my eyes are more or less blue.”

Making statements instead of asking questions during an interview is hard to do, but it moves the responsibility for editable footage away from your hapless interview subject to you (where it belongs). This, in combination with shifting the movie’s data disclosure requirements away from the interviews and designing the movie around the interview subjects’ passions means that the interviewees, who are, after all, the subject matter experts, will most likely say the right things in the interview.

Keep all others, especially the interviewee’s handlers, out of his or her eye-line. Look the interviewee in the eye. React to what he or she is saying. Authentically. Do not look down at your notes. If you need to look at notes; pause the interview to do so. This will encourage the interviewee and focus his or her eyes on you.

Keep all others, especially the interviewee’s handlers, out of his or her eye-line. Look the interviewee in the eye. React to what he or she is saying. Authentically. Do not look down at your notes. If you need to look at notes; pause the interview to do so. This will encourage the interviewee and focus his or her eyes on you.

Let the interviewee talk. Guide the conversation, but don’t stop him or her every half sentence with corrections. Listen for passions; follow up on them. Listen for edit points, for complete bites. Don’t worry about what doesn’t work: listen for what does. If you haven’t heard something that you need, prompt for it.

If the subject brings a prepared statement and insists on trying to recite it, get him or her to read it for voice-over before the interview. This will get the interviewee’s responsibility for data out of the way so he or she can simply talk about what is important.

You may still have problems: some people always speak in fragments. You may not be able to get the subject to open up to you and speak honestly. He or she, unclear on how media works, may not be able to repeat an answer, especially without saying “like I said before.” Used to acronyms or abbreviations, he or she may not normally use the full product or company name. The person may ramble.

If it’s not working, gently introduce the necessary rule. “Great! Tell me that again, but call the company Neologism Limited. We need you to use the whole name.” Or “great! We always bring up the same topics over and over, but we only use them once. Try not to say ‘like I said before.'”

At the end of the interview, feel free to feed lines to the subject if necessary. If you simply cannot get the nouns and such that you need, get them as wild lines at the end of the interview.

The main thing is to leave the interview subject free to converse honestly about the topic with a genuinely interested (though strangely silent) interviewer.

Interviewing for movies can be difficult. It is a joy to watch an accomplished professional doing it. It is much easier to understand, though, if you first put yourself in the interviewee’s shoes.

Don Starnes directs and photographs movies and videos of all kinds and is based in Los Angeles and the San Francisco Bay Area. He has photographed interviews with many of the people who invented the future.

Also by Don Starnes:

![]() Monitors and filmmaking

Monitors and filmmaking

The difference between a movie and a video is that a movie is created in the filmmakers’ minds and a video is created on a monitor.

![]() Money

Money

It’s the Producer’s Invitational Pancake Breakfast. Just as the producers are cutting into short stacks with their plastic forks, all of the doors are locked…

![]() Blocking before coffee

Blocking before coffee

Feature film: first day. The first-time director is 45 minutes late. Finally, he shows up: harried, stubbly, preoccupied and exhausted…

![]() How to get trained

How to get trained

Hint: it isn’t by reading this.

![]() Preview: the Mini XTC 9250-XL

Preview: the Mini XTC 9250-XL

Just in time for NAB, the 9250-XL is everything that a producer could want in a camera. The revolution has begun…

![]() DIY DCP

DIY DCP

How to make your own digital theatrical ‘print’ using Final Cut Pro, After Effects, guerrilla DCP software, pluck and maybe a little help from your friends.

![]() Keying and compositing in NukeX

Keying and compositing in NukeX

Skitch a ride up its steep learning curve using my template and tutorial.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now