With the news of ProRes being added to the iPhone 13 Pro and Pro Max, the gap between phone and professional camera is getting smaller. Add to that the fact that you may well have an iPhone in your pocket on a shoot and it gets pretty tempting to use it as a B or C cam for an extra angle to give your editors (and we know editors love coverage!).

This is not a new phenomenon – I don’t know about you, but over the last couple of years the pandemic has meant I’ve had a lot of phone footage in my projects, where documentary subjects have had to self-shoot or because of decreasing budgets.

A feature documentary I cut for Discovery+ a couple of years back occasionally used an iPhone for the third camera and as an editor I was really happy to have that angle to cut to. The colourist was able to get a pretty good match and no-one was any the wiser.

Test Setup

I wanted to see how far things have come – pitting the iPhone 13 Pro against the Blackmagic Pocket Cinema Camera 4K, which is a fairly popular affordable pro camera and, as it happens, about the same cost as the iPhone. I bought a cold shoe phone holder from Ulanzi and went out to the local beach to shoot a few test shots with my DoP and colourist Freddie Reed, who graded them afterwards. I shot in SDR (turning off Dolby Vision HDR) and mostly on the main (1x) lens which has the largest sensor and best quality.

I’d already seen enough tests on YouTube to know that I wanted to avoid the high shutter-speed look, so I put a variable ND filter on the phone to avoid that. As I already had a 77mm Tiffen filter, I bought a cheap snap-on filter holder and some step up rings – as a proof of concept more than anything. I would recommend if you are going to be filming with your phone regularly that you hit up Moment or Moondog Labs or find any case with a bayonet mount and get a compatible ND filter that will lock into place – I lost a few shots when the filter wasn’t lined up properly.

Here are all my test shots back to back:

ProRes vs LOG

The first thing I wanted to test was whether ProRes was better than the native iOS camera app’s H.264 or H.265 as well as shooting in LOG in the FiLMiC Pro app (you can’t shoot LOG and ProRes).

The native camera app records at a pretty low bitrate (around 40 Mbps) and so breaks pretty easily – any fast movement or detail in the shot and you quickly see a loss in detail and compression artifacts coming into play. This is fine for non-professional work and probably desirable so you don’t fill up your phone and cloud storage too quickly, but not good enough for a proper shoot.

FiLMiC Pro, as well as other apps like ProTake, can increase the bitrate significantly and this improves the quality and deals with most of the issues I was seeing in the native camera app. FiLMiC Pro Extreme for example records at 300 Mbps at UHD 4K.

FiLMiC Pro also gives you the ability to shoot 10 bit LOG and you might think that would be the best way of matching a pro camera that also shoots in LOG. But pixel peeping on a good monitor showed me that ProRes comes out significantly better, both in terms of colour and detail and sharpening. This isn’t all that surprising as ProRes HQ ups the bitrate again to around 700 Mbps.

The quality of the ProRes is significantly higher than the LOG, seen in the face particularly. It also has less sharpening baked into the image, though it still has a lot and this is the most obvious difference between it and cameras that emulate a filmic look.

We tried grading a few of the LOG shots and it was much harder to get the colours to match the Pocket. ProRes was the clear winner so the rest of the comparisons only feature the iPhone 13 ProRes against the Pocket 4K. We still filmed the ProRes in FiLMiC Pro for greater control over white balance, shutter speed and ISO.

Grading the iPhone ProRes

For the grade, we used a Kodak film emulation PowerGrade from Juan Melara and in the limited time we had, tried to match the shots. Even shooting ProRes, matching the shots was difficult, especially the sky. It often needed a power window to separate out different parts of the shot. While we were able to get pretty close on most shots (aside from the sharpness which needs to be dealt with separately), it’s worth noting that shooting on the iPhone does incur extra grading time if you have high standards and are matching to a certain look, though this will depend on what camera and lens combo you are matching to – some will match better than others.

If you don’t have access to a high-end colourist, you might be interested in CineMatch by the makers of FilmConvert. It aims to match the colours of various cameras, including the iPhone, to give you a really good start in your grade and take away a lot of the guessing for you. You can test it out using the free trial.

Sharpness

How sharp a moving picture appears depends on a number of factors. True sharpness comes from the resolving power of the lens combined with the size and resolution of the sensor. Then there is digital sharpness that can be added either in camera or in post, which is something manufacturers can use to improve the apparent quality of their hardware. It’s also a matter of taste and genre to some extent with indie films in particular prizing a softer look. Even high end films try to lose some of the digital feel of modern cameras – Dune was shot on Alexa LF, transferred to 35mm and then scanned back to digital!

I found that on some of the shots with a lot of detail in the frame, the iPhone’s over-sharpening looked pretty nasty to my eye, but on other shots it wasn’t too bad. This is probably better seen in the YouTube clip above as we are used to liking sharpness in a photo (that’s why feature films employ an on set photographer rather than using grabs from the film).

Either way, you want your cameras to match, so this is an important part of the process. I tried both sharpening the Pocket & blurring the iPhone footage (and got on best with FilmConvert’s fine grained blur). It’s worth noting that the Nikon 28-70mm f/2.8 we were using is not a particularly sharp lens and the image would come out much sharper with a native micro four-thirds lens. But we prefer the Nikon and it matches better to our Arri Alexa. I would dearly love Apple to give us the option of less baked in digital sharpness on the iPhone – on some Android phones, FiLMiC Pro does give you that option, so I think it would be possible. Also, shooting LOG in ProRes would be a handy addition.

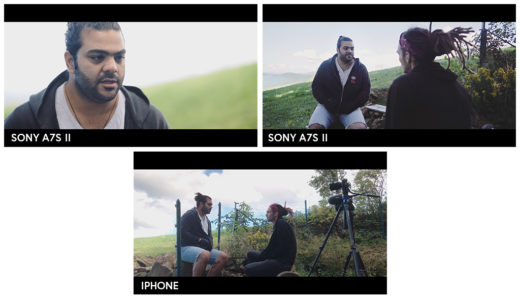

I tested a typical interview setup and found that sharpening the Pocket 4K footage was the best approach to matching the two cameras and with that I was able to get a pretty good match.

The iPhone 13 Pro’s superpowers

It would only be fair to point out where the iPhone excelled. Without a dedicated macro lens, the iPhone was able to get an ultra close up shot the Pocket couldn’t. And with in body image stabilization (IBIS) on the main wide lens, the handheld walking shot was much smoother on the iPhone. I didn’t test it, but the Apple marketing videos are keen to show off the waterproofing on the phone which means it can be used as an action cam in circumstances where you couldn’t use your main camera.

I’ve watched a number of tests of the new Cinematic mode as well as using it myself and my conclusion is that it’s not good enough yet for professional productions and best reserved for shots of friends and family, where it’s a lot of fun. But we saw the edge detection of portrait photos take a few years to really emulate DSLRs, so I’ve no doubt this will get there too. Also the natural bokeh now from the larger sensors is pretty impressive for a phone.

HDR

I didn’t shoot in Dolby Vision HDR for these tests as I was making a SDR video and from what I’ve seen it’s only worth shooting HDR if you need to deliver HDR. That said, the iPhone still seemed to use some sort of automatic HDR to SDR bracketing in some of the high dynamic range situations like shooting inside the beach hut. Whether you want this or not would probably depend on the circumstances & it would be nice to have control over this.

Other issues

Getting the large ProRes files off the iPhone is a real pain, whether wirelessly or wired. You have to allow quite a bit of time for it. This one downfall alone is enough to put some people off from using the iPhone professionally and I think Apple really needs to sort this out (as a creative engineer already showed it’s possible to do).

There is also the issue of the ProRes files still being VFR (variable frame rate) in the native app which is quite annoying as NLEs can struggle with this. I found though that shooting ProRes in FiLMiC Pro recorded constant frame rate clips, which is another positive of using it.

Conclusion

There’s no doubt that it’s impressive how good the video footage is on the iPhone 13 Pro and shooting ProRes is a big part of that, though it would be fantastic if Apple allowed more of the raw image to be captured (whether actually using ProRes RAW or just allowing less computational work to be baked in). They also badly need to move to USB C for quicker data transfer.

With a bit of effort however, footage from the iPhone can be used in proper productions & that means that it may be worth getting your phone out of your pocket and using it as a B or C cam on your next shoot. Just hope that no-one wants to call you!