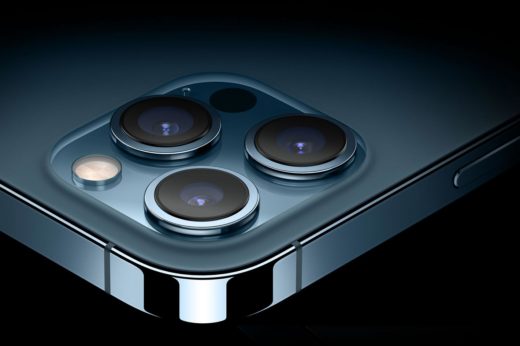

What sort of camera has seen the most development over the last decade or two? Big-chip options for single-camera drama? Highly-portable, fixed-lens designs for documentary and news? Maybe stills cameras, which have actually developed an ability to shoot video they previously lacked.

Well, no, it’s cellphones, by a country mile, and right now a sort of watershed is being crossed as rumours abound of the iPhone 13 recording to ProRes.

Paper specs and processing

There are a number of ways to interpret that, but in a wider sense film and television seems almost backward by comparison to the white heat of recent phone development. Arri is still selling essentially the same sensor technology it launched in 2010, when the iPhone 6, with its 8-megapixel camera, was current. The iPhone posted some surprisingly decent numbers even then, being capable of at least some kind of 1080p video at sixty frames a second, though the sheer rate of progress since has been overwhelming in terms of megapixels per year.

Purists will rightly frown at the obsession with paper specs, but really, the hardware is not the whole story. Much of what makes modern cellphones look good is postprocessing, which polish a lot of subjective gloss onto mediocre cameras. The final stage of that processing is invariably compression. JPEG stills are often fine, although the sort of real-time H.264 encoding done by phones often leaves something to be desired. It seems that Apple may have concluded that its cameras (and their associated postprocessing) now justify a better codec.

This is no great surprise in the context of the Red-Apple disagreement over in-camera raw recording, which always seemed to beckon phones. Atomos would hardly thank Apple for making it possible to routinely put ProRes Raw in cameras. Putting ProRes Raw in a phone would make as much sense as putting it in any other kind of camera, although that might mean a per-phone stipend to another company at this stage. Vanilla ProRes, not so much.

ProRes and friends

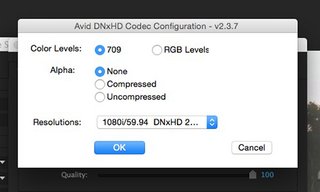

As to the technological realities, it’s easy to take on trust that ProRes is an arbitrarily better codec than H.264, although that depends very much on the semantics of the word “better”. The actual techniques underlying ProRes are comparatively elementary, being of much the same thinking as Motion JPEG, DV, DVCPRO and DNxHD. It’s a careful balance of compression performance over required work to decompress and (particularly, in a mobile device) to compress the pictures. In an ideal world, if by “better” we mean “better picture quality for a given bitrate,” H.264 is better than ProRes.

As a practical matter it’s more likely that any given ProRes implementation will support things we want for higher-end work, such as 10 or more bits. XAVC, AVC Intra and AVC Ultra do support 10 and 12-bit encoding and I-frame only files, and they are both varieties of H.264. Whether the H.264 encoder hardware in a given cellphone would support doing those things is another matter, though. What we’re talking about here is whether the specific implementation of ProRes on a phone is likely to be better than the specific implementation of H.264 on that same phone, and, well, yes, it is, because the intent is different.

The risk

…is that better recordings are more likely to reveal the fnords in cameras that, as we’ve seen, rely on a lot of postprocessing. It seems unlikely a cellphone manufacturer would let that happen, but the demo pictures used to promote cellphone cameras are often stills, and phones can do all kinds of things to stills that they can’t do to video. One particularly powerful technique is to average multiple exposures, and that’s been making cellphone snapshots of night exteriors look supernaturally good for a while. It relies on the phone’s ability to rectify camera and subject motion before the averaging can happen, something it can’t practically do to video.

Perhaps most crucially, cellphone pictures are designed to look good on cellphone displays, and while some of those displays might have HDR-level brightness to remain visible outdoors, any attempt to grade phone footage tends to reveal exactly the sort of limited dynamic range and heavy-handed noise reduction and sharpness enhancement we’d expect from a tiny sensor with a lot of photosites on it. This is no great calumny given how well they usually do work, and the best of them are starting to step away from the worst of the problems. Certainly, coarse compression, particularly inter-frame compression of the sort typified by phones, makes everything worse.

It remains to be seen if less-coarse compression can make everything better, and whether cellphone cinematographers are ready for video that takes up five and a half times more space than they’re used to. Experience suggests that this will mainly be seen as a good thing.