Kirk Baxter was attracted to cinema from a young age by films such as E.T., Raiders of the Lost Ark, and Star Wars. These “popcorn accessible” movies drew him in and fueled his aspirations. He started working for an Australian production company at age 17 and quickly recognized his affinity for editing. But never did he dream that one day he would be involved in the kinds of productions he works on regularly with filmmaker David Fincher.

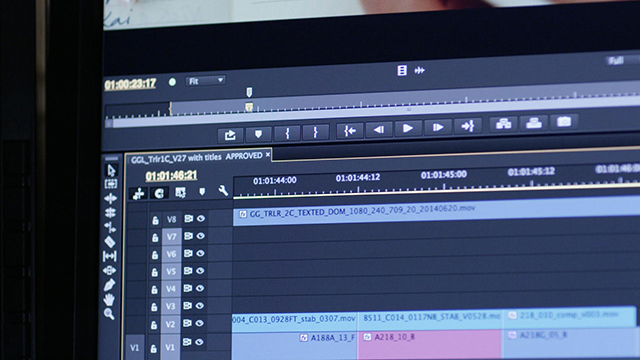

As a two-time Academy Award® winner, Baxter has teamed with Fincher and his post-production crew on film and television projects, including The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, The Social Network, The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo, and House of Cards. For Fincher’s latest film, Gone Girl, “Team Fincher” took the workflow to a new level using a production pipeline built around Adobe Creative Cloud video applications, with Adobe Premiere Pro CC as the hub.

Adobe: How was the process of switching to a new NLE?

Baxter: Each time you switch to a new editing program you’re a bit nervous and it’s mostly because each job that you do, be it a movie, commercial, or music video, is an opportunity for failure. Everything has to be done to the best of your ability, like it’s the first job you’ve ever done, because you’re only as good as your last job. All jobs have a pile of pressure on them, all of them have a timeline on them, and all of them are riddled with expectations. If my process is being slowed down because I have to fumble with a new way of working it can be really frustrating.

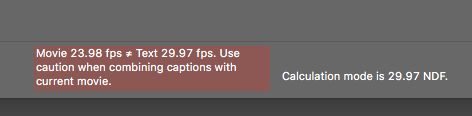

I found that the learning curve to get onto Premiere Pro only took about two days. Thankfully, when I switched to Premiere Pro I was doing a Fincher project where the audience is generous and David is always understanding about learning something new. It was great to have technical support from Adobe. Plus, I had Tyler Nelson and the main thing for me was that Tyler knew Premiere Pro better than I did, so if I had questions I could just turn to him.

Adobe: Why did you make the switch?

Baxter: We switched to Premiere Pro because David, Tyler, and Peter Mavromates, the post-production supervisor, said this is what we need to do in order to streamline our process, bring everything in house, and make post-production cheaper so we can do more, faster, and be smarter about the whole process. I’m the easiest person to please in terms of how the software operates. That’s why my transition to Premiere Pro was so fluid and didn’t take long at all. The interface, is great and it works as well as, and sometimes better than previous programs I’ve worked on. It does everything that I need to do and it does it really well.

Adobe: How did you turn around the massive amount of content Fincher shot each day?

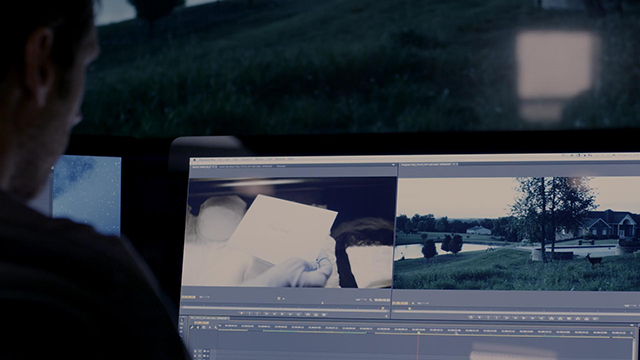

Baxter: There’s an approach that works really well for David because of the style that he shoots. I watch the last take of each scene and just from viewing it once I can process what the mathematics are and spot the tent poles. When you work out the rhythm of the scene, you can break up master takes or main performances into chunks. From there I can look at all the takes in reverse order and see how he’s refined a scene to make it tighter and more precise.

It’s very rare that one take is the very best from start to finish for every line that is read, so breaking a scene up is important. I’ll go through the last take and add in edit marks as cutting points, and then my assistants will assemble all of the takes so line readings are repeated. I’ll go through and select all of the best of it, hand it back to them to assemble my selects from wide to tight in scene order.

After I’ve done that for a big scene we have about 15 minutes of material and it’s probably taken us all day to get to that point. That’s what I’ll share with David.

Adobe: How do you share the selects for quick feedback?

Baxter: We use PIX to share clips with David when he’s on set. PIX is frame accurate and you can draw all over it like a football play. For example, David might circle someone in the background who is staring at the camera to show me what’s wrong with a particular take.

We put everything through PIX – the visual effects, music, sound design, marketing – so it’s all in one place. Whether David is on set or in his office, it’s all constantly flowing to him and he’s always part of the process. Because we’ve been able to work so closely together throughout shooting, when the director’s cut begins we’re about 10 days from having a first assembly. Then the director’s cut is all about fine cutting and perfecting.

Adobe: What’s the best way to get feedback from Fincher?

Baxter: With David, the long way around is always the best way. We cut every scene as if it is the only thing that exists. If I include David in selects he knows I’ve really looked and scrubbed and his voice is being heard.

At first, it’s about fleshing it out, getting the maximum out of a scene, which is usually longer. Then the job becomes about how to remove as much screen time as possible without losing any content. That’s why there are so many split frames and so much dissecting within a frame.

Adobe: How did you use split screening to advance and delay dialogue?

Baxter: If there are two actors on screen at the same time, there’s a high probability that I’m splitting a frame and choosing the best performance for each actor when they’re interacting or getting the actors’ response times to be faster. It’s self-evident when you start going too quickly, but when you keep that pace up, a pause means so much more.

Adobe: Tell us how the process of repositioning and stabilization has changed over the years.

Baxter: When we did The Curious Case of Benjamin Button, David shot for the full frame of what you see, so if the camera operator screwed up a performance it was dead and we had to use another one where the camera was better. Now, when he shoots in 6K there is so much extra space in the frame we can move shots around later, reframe, stabilize, and perfect a shot. For me, it’s helpful because I’m picking the performances that are the best, not the camera work that is the best.

David doesn’t want the fingerprints of filmmaking to distract the viewer from the intention of a shot or the feeling of a scene. For him to get a big bump in the middle of something or for the framing to stray is the same as an actor looking at the camera and smiling, saying, “Hey, there’s a bunch of filmmakers back here.”

Adobe: How do you balance the technology with the storytelling?

Baxter: I don’t think one takes away from the other. The storytelling part is always consistent, the technical side is just in support of telling a great story. David has a great understanding of all of the tools available to him and will bend them to his will, or question them, so a production can be made smarter and better and faster and leaner. It all just benefits the process of how to tell the best story.

Adobe: Tell us about your new company.

Baxter: EXILE makes what I do more than just me doing a job. In a lot of ways it’s like finally becoming a grown up, with more responsibility and accountability for others. There could be a job that I’m not interested in or excited about, but if I know one of the other editors is going to gain by my involvement I might do it for the union of others.

It’s a great time to start a company because we can make really smart, lean, clever technology decisions. It doesn’t have to be wildly expensive anymore. I saw the way the post-production workflow moved on Gone Girl, and I’m applying that to the commercial work we’re doing at EXILE. I think it’s a very good time to do something smart.

View Kirk Baxter’s work here.

Learn more about Adobe Creative Cloud

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now