On my annual pilgrimage to NAB this past April, I decided I would finally check out the National Atomic Testing Museum in Las Vegas. I’d driven past it many times in the past but never took the time to go in. During the tour, I was gratified to see they had included a small homage to a historic event in the development of television.

I am familiar with the lore surrounding the first live telecast of an atomic bomb test. KTLA plays a significant role in the development of the television industry in Los Angeles, the subject of a book I’m currently researching. This episode represents just a sample of the groundbreaking events in this independent station’s history.

On Tuesday, April 22, 1952, reporters and photographers of the nation’s press were invited to witness a test of an atomic bomb for the first time. Until then, the U.S. Government conducted the tests in secret and did not publicize the events. Residents for hundreds of miles around Las Vegas would only know a test had taken place when they saw a bright light in the sky and experienced a shock wave that sometimes knocked out windows.

The Atomic Energy Commission (the governing U.S. agency in 1952) was under pressure to open up. It was finally time to let the public in on what was going on. So, only a few weeks before the next test, the AEC relented and the press was invited to cover Operation Open Shot. They gathered in the Nevada desert at Yucca Flats on a location dubbed “News Nob,” a rock outcropping that allowed for an unobstructed view of the atomic blast.

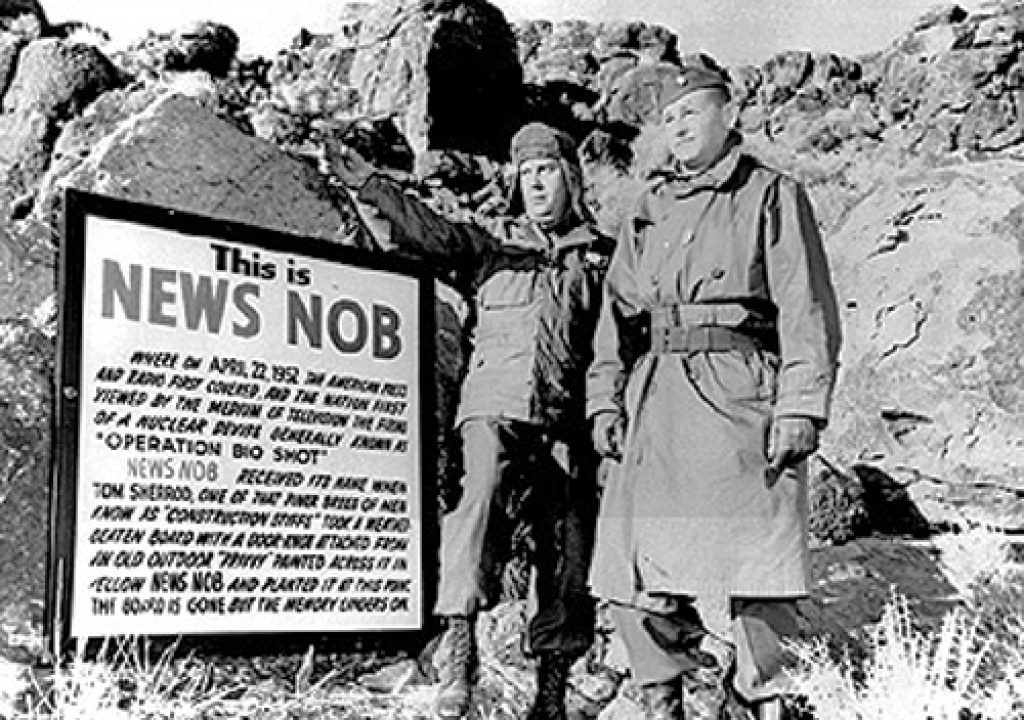

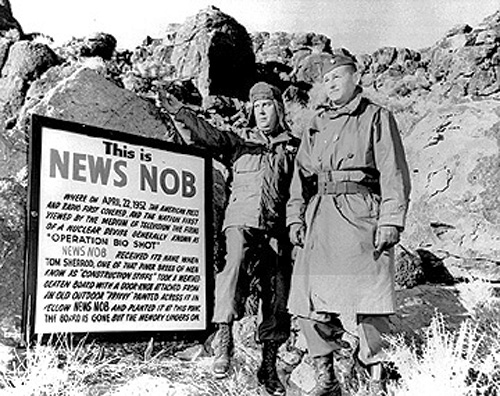

This sign commemorates the first atomic test open to the press and media and is exhibited in the Museum of Atomic Testing in Las Vegas, NV. It reads, in part, “This is News Nob where on April 22, 1952 the American press and radio first covered, and the nation first viewed by the medium of television the firing of a nuclear devise generally known as “Operation Big Shot.” Photo courtesy of National Nuclear Security Administration / Nevada Field Office

Television was invited, too, but in those early days, the telephone company in the form of AT&T Long Lines controlled long distance television transmission. They told the television networks it would take six months to build a microwave link to Los Angeles (television in Las Vegas was still over a year away). So the national networks didn’t think it would be possible.

Enter Klaus Landsberg, the Vice President and General Manager of KTLA in Los Angeles, the first television station to be granted commercial status west of the Mississippi. Landsberg had already made a name for himself by exhibiting a keen knack as a programmer in hooking and keeping audiences who were trying out television for the first time. He was famous for dispatching remote units around Los Angeles and inventing the live coverage of entertainment, news and sports that is television as we know it today. Landberg was also an excellent engineer.

Klaus Landsberg, Director of experimental television station W6XYZ when it went on the air in 1942. Under his guidance, it became the first commercially licensed television station west of Mississippi when it became KTLA Television on January 22nd, 1947. From Ancestory.com

In the early days television pioneers were constantly experimenting. Everything was possible if you just tried. So when the networks and the government asked Landsberg to take a crack at the assignment, he jumped at the opportunity to bring the signal into Los Angeles. It would then connect with the new transcontinental television circuit, be transmitted to the networks in New York and subsequently to the entire country. With less than three weeks to make it happen, Landsberg and his team of exceptional engineers got to work. One of the engineers on Landsberg’s team was future Emmy award winner John Silva, the inventor of the “Telecopter” – live images from helicopters in flight.

In this “Emmy TV Legends” interview, John Silva’s first hand recollections of KTLA’s live coverage of the A-Bomb begin at 6:47

The longest microwave transmissions up to then had been in the vicinity of 40 miles. But one of the hops would have to be 140 miles, a shot across California’s Mojave Desert between Mount San Antonio in the San Gabriel mountains outside Los Angeles and an unmapped mountaintop known only as Mount X just inside California near the Nevada border.

Silva believed he had the solution to the distance problem. He had found a source for a newly designed amplifier for the microwave equipment that would increase transmitting power by five fold. Silva’s calculations concluded that with the booster, the transmitter would provide just enough power. But to even try the equipment, they first had to get it there. Mount X had no roads and was unreachable by land vehicle.

The project had the support of the U.S. Government and Landsberg used it to his best advantage. With only five days left, KTLA was supplied with two Marine helicopters to lift equipment and personnel into place on Mount X. The relays along the path were carefully aimed and finally power was applied.

It worked.

Once the signal path was established, Landsberg left It on 24 hours a day. KTLA Engineers camped out on the mountaintops, maintaining their transmitters and generators while living in tents for over a week.

Reporters, photographers and newsreel cameras gathered to witness the detonation (Note original “News Nob” sign in the center). From the General Records of the Department of Energy, 1915-2007, via the National Archives

The morning of the bomb drop, a small army of media arrived early to set up at News Nob. The test was scheduled to go off at 9:30am, Pacific Time. Landsberg began feeding pictures to Los Angeles and the networks at 8:45am. At 9:15am all was ready. The newsmen prepared to put their dark goggles in place as the moment of detonation approached.

All was going well. That is until 9:16am. That’s when the power went out. Everything in the remote unit went dark.

Moments before the bomb was dropped, a power failure hit News Nob and everything associated with television was dead. At the microwave relay point on top of Mount Charleston, 40 miles away, the signal from News Nob was suddenly no longer there.

But Landsberg had the foresight to establish two backup cameras on the mountain. Without hesitation, Charles Theodore, the engineer manning the switch point on Mt. Charleston switched to a camera at his location. Cameraman Robin Clark had focused in the general area where the blast was to take place. He hit the mark perfectly.

The blast was so large, it even filled the frame of Clark’s distant camera. Everyone viewing the event thought nothing of the switch and, according to Broadcasting magazine on April 28th, 1952, an estimated 5,000,000 viewers across the United States witnessed the awesome power of the detonation of an Atomic Bomb live in their living rooms.

Reaction heaped accolades and commendations on KTLA and Landsberg would continue to experiment and come up with new forms of programming right up until is untimely death from cancer in 1956.

Mobile unit at News Nob/Camp Mercury control point. Klaus Landsberg stands to the left of the camera. Note the ropes staked to the ground to minimize movement of the truck not only from the desert winds, but the shock wave of the blast. © KTLA5, Tribune Company. All rights reserved.

There are some sources that erroneously identify the first broadcast as taking place in February, 1951. Stan Chambers was with KTLA virtually from the beginning. In his book “KTLA’s News at 10,” he confirms there was A-bomb coverage live on KTLA early one February morning in 1951. It, too, was the work of Klaus Landsberg.

However, the origination point was KTLA’s transmitter site on Mount Wilson, hundreds of miles from the Nevada test site. Landsberg had heard there would be a test. He reasoned that by pointing a camera in the direction of Las Vegas they could show the bright light from the bomb at the moment of its detonation. KTLA’s Dick Lane was the voice on Mt. Wilson with KTLA newsman Gil Martyn on an audio circuit from Las Vegas narrating what he saw as the bomb went off. After it was over, it was learned 30,000 Los Angelenos had risen at 5:00am to see the instant of bright light. It was one of the motivating factors for the government opening a test to the press a year later.

As I left the Atomic Testing Museum anticipating my long walks through miles of booths and exhibits showcasing all the television gadgetry we now take for granted, I took a moment to look up at Mount Charleston off in the distance and appreciate the unbending confidence and nonstop effort by those 1952 KTLA engineers lead by Klaus Landsberg. In that short period, they advanced television technology so far with so little so fast.

Operation Open Shot goes off and an estimated 5 million Americans see it live! © KTLA5, Tribune Company. All rights reserved.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now