While every photography school, workshop and online course teach the importance of the decisive moment, the truth is that Henri Cartier-Bresson doubted the term had any real meaning, as he suggested when he annotated Martin Parr’s personal copy of his book “The Decisive Moment” so it would read ‘The More or Less Decisive Moments’, effectively hinting at the plurality and ambiguity of its meaning.

The fact is that the title The Decisive Moment, chosen by the English language publisher of Henri Cartier-Bresson’s book, in 1952, is an example of something lost in translation. The original title, in French, was Images à la Sauvette, which meant images taken in a hurry, by someone that tried to not be seen. We coin it, these days, as Street Photography, but the “decisive moment” caught up and became a fundamental notion in the study and practice of photography.

According to information available on Magnum’s website about the series now published, “The decisive moment is often described as an ephemeral or spontaneous composition perfectly captured by the photographer; as Chien-Chi Chang notes of his image, “the decisive moment is a moment of grace, when the light is right, the circles are in harmony, the legs upraised just so. Click.”

It may be so, but the problem is that the concept of the “decisive moment” led many to believe that the photographer would just press the shutter at that exact “decisive moment”, making a single image that showed, some say, his or her ability to get things right. Well, it took Magnum 64 years to assume that “the decisive moment is also an expression open to interpretation, playfulness, and even rejection: this project explores what the concept of ‘decisive moment’ means to Magnum photographers.”

On its website Magnum states that “as we enter our 70th year, we take a look back at one of the photographic theory famously associated with agency co-founder Henri Cartier-Bresson with The (More or Less) Decisive Moments, asking Magnum photographers to explore what the notion of decisive moment means to them, and how – if at all – it manifests in their own practice. Photographers have responded with a chosen image and a supportive text, opening up something of a discussion.”

From the testimony of multiple photographers one understands that many were never at ease with the concept of the “decisive moment”. One of them, Alex Webb, writes that “Probably, no photographer has influenced me for as long as Henri Cartier-Bresson… ever since I first saw my father’s copy of The Decisive Moment in the late 1960s, I’ve been uneasy with the title. The notion of a ‘decisive moment’ seems just too pat, too unpoetic for such a complicated vision. Years later, it was gratifying to discover that the original French title was Images à la Sauvette— ’Images on the Sly’— a humbler notion more in the spirit of his early street photographs, work that embraces the mystery and uncertainty of collaborating with the world. ‘It is the photo that takes you,’ as he once said.”

I believe Webb’s thoughts reflect what many think but dare not say, or did not dare to say. I am not sure, though, if this series of photographs and article will help to change things when it comes to the study of photography. Can this event take us away from myths that have been nurtured for decades? If it did, it would really pay hommage to Henri Cartier-Bresson, whom had already signaled we was not comfortable with the “decisive moment” theory when he annotated Martin Parr’s personal copy of his book.

For a photographic tour I led last May, I prepared, as usual, a series of texts and slideshows, and in doing so I wrote a series of notes under the title “The myth of the decisive moment and contact sheets” which I think makes sense to add here, as it confirms my belief, one which Magnum’s seems to accept now.

Along with the term “decisive moment”, a series of other myths grew around the figure of Henri Cartier-Bresson: he never used flash, he never cropped a frame, he never retouched and he used a 50mm lens. Well, for the HCB retrospective held in Paris in 2014, the curator of photography at the Centre Pompidou, Clément Chéroux, found evidence that Cartier-Bresson did own a flash, that he did carry a number of lenses, and so on. The simplified outline that Cartier-Bresson presented to the world was not false but nor did it tell the whole truth.

The best evidence of HCB’s working routine is, after all, shown in something that was essential at the time: contact sheets. Through HCB contact sheets one understands that the photographer took multiple images of each scene, searching for the right composition. It was a normal practice at the time and one still kept today for those using film. The library module in programs like Lightroom does exactly the same for digital files.

Those familiar with the series of books from Magnum showing contact sheets of different photographers have there the exact proof of one thing: there is not one but, at least, two decisive moments, one where the photographer chose were to wait for something to happen, and the other when he chose one frame instead of another.

Photographer Stuart Franklin suggests exactly this on his words for the new series from Magnum. When describing the image he selected, he says that “this picture, from Moss Side, Manchester, chimes with the larger meaning and the spirit of Cartier-Bresson’s influence on me. I took two or three rolls of film of this scene as it unfolded, but there is only one picture that works, where all the elements come together: timing, composition, geometry and the situation as I wanted to remember it.”

For Stuart Fraknklin, “the decisive moment, when you think about it, is a one-dimensional concept. It deals with time or timing. It fails to do justice to the larger meaning behind Henri Cartier-Bresson’s idea or the 20th century master’s elegant and much more broadly decisive approach to photography. This includes the decisive composition, geometry, quality of light and subject.”

Through this new series Magnum may well contribute to debunk the myth of the “decisive moment”, but let’s be realistic, it has been tried before, by authors as Eric Kim or John Barbiaux, without much success. It is difficult to change a perspective which is so popular, and that is always presented as an essential truth of the learning process in photography. Even if it is a myth, like the Rule of Thirds…

Looking at the contact sheets on Magnum’s books or elsewhere, one understands that they where essential for the creative process. After a frame was selected a new aspect of the whole process started: the darkroom edition. With film that meant giving it to a printer. In fact, it is usually said that behind a good photographer there is always a good printer.

One of the most popular examples of such truth are the contact sheets and lab images from Pablo Inirio, master darkroom printer at Magnum Photos in New York. After one image is chosen, a print is created, upon which the printer will annotate the different operations needed to create the final photograph. It’s a process not much different from what is done in Photoshop – after all, the essential tools from Photoshop emulate those present in any darkroom -, and serves as one final and important message: there is no “decisive moment” but a series of photographs from which the photographer picks the one that better depicts the action or message, and there is always some work to do to get from the original negative or file to the final photograph that is shared with the world.

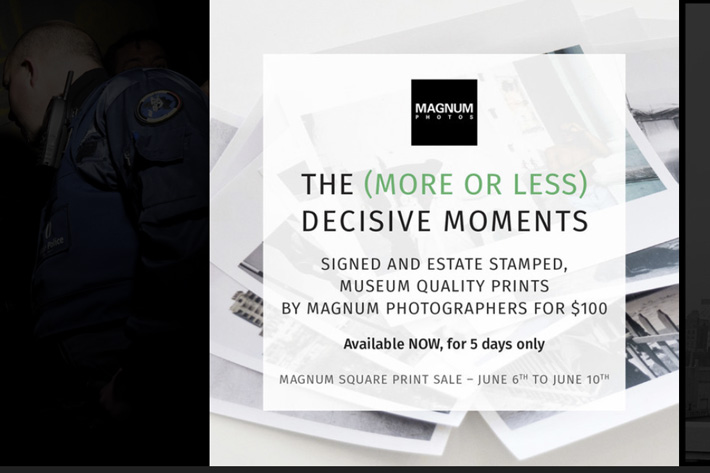

The news now is that for five days only, prints by Magnum photographers which respond – or question – to the meaning of the decisive moment, will be available to buy as signed, museum quality, 6×6” square prints, exceptionally priced at just $100. You can order the prints through the Magnum Shop. Apparently, this is a one time event and the “more or less” will become history again.

I wish Magnum would go ahead and, more than a series of prints for sale, did a whole book under the title The (More or Less) Decisive Moments, to offer on their online bookshop, along with the initial The Decisive Moment. I would buy such book, to put besides my Magnum Contact Sheets. I think it would be the best homage the agency could do to Henri Cartier-Bresson. After all he hinted exactly to that 62 years ago. Better late then never!