Today, we think nothing of clicking our remote and have live images from somewhere else in the world appear on the screen. Push a few buttons on our computer and loved ones living far away appear. But in television’s early days, a live program meant we were watching a local program.

Every station that went on the air was an island relying on couriers and the mail for any program not made by the station itself. Within a few years, however, the gestation of TV’s transmission system for the American continent developed in little geographic pieces like a jigsaw puzzle. Because video signals use so much more bandwidth than audio, the existing telephone network was not sufficient to handle the load. A whole new infrastructure was needed.

Most Americans watched shows produced live for New York weeks later when their local station received a “kinescope” of the show. With videotape still years away, the only way to record a show was to point a motion picture camera at a video screen, process the negative, make prints and ship them to their affiliates across the country.

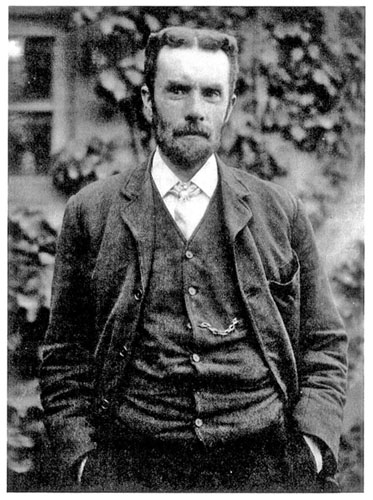

We hear the term Broadband used to describe our home Internet and/or cable service. Before 1936, telephone lines were on twisted copper wire. Then the American Telephone and Telegraph Company (AT&T) began experimenting with an 1880 invention by Oliver Heaviside – Coaxial cable. Coax, as it is nicknamed, is the first form of broadband. Heaviside was a self-taught British electrical engineer who later became best known for the layer in the ionosphere named after him that influences radio waves to “skip” and respond to the curvature of the earth.

Oliver Heaviside – Inventor of Coaxial Cable

AT&T Scientists Lloyd Espenschied and Herman Affel later applied for a U.S. patent as they improved on Heaviside’s work. Back then, AT&T was part of the Bell Telephone System of regional telephone companies (Bell of Pennsylvania, Pacific Bell, Southern Bell, etc). For many years AT&T had a virtual monopoly on telephone service (and later, radio and television distribution) in the U.S. until in 1982, the courts decreed its breakup as new technologies arrived on the scene.

In addition to providing telephone service to the highest percentage of homes in the U.S., the Bell System also maintained a manufacturing operation (Western Electric), research and development arm (Bell Laboratories) and AT&T Long Lines. Long lines provided the glue that enabled the regional systems to interoperate. In 1949, if you placed a long distance call from Los Angeles to Pittsburgh, Pacific Bell transferred the call (by hand, through a telephone operator inserting a plug into a jack) to AT&T’s long lines network that then handed it back to Bell of Pennsylvania to complete the call.

Because of their common carrier status and the infrastructure they had in place, AT&T handled all radio transmission lines, including those of the major radio networks throughout the nation.

As the nation grew, orders for telephone service innundated the phone companies and, with the additional specter of television on the horizon, AT&T had to invent a way to multiplex calls to satisfy the increasing demand. Thus, the coaxial cable, the first broadband transmission medium was born. That first experimental path of coax in 1936 was installed between New York and Philadelphia. The technology of the time could only carry 480 telephone calls or one television signal.

Coaxial cable used for muliplexing telephone calls or carrying multiple television signals, 1946.

Concurrent with the development of coax was microwave relay. Microwave was developed in the military during World War II. With the war over, use of the technology for civilian purposes became possible. Limited by the curvature of the earth, a “line of sight” system of repeater towers spaced 25-30 miles apart was designed so telephone and television signals could travel from city to city. The first of these was established in 1947 with a successful connection between New York and Boston via seven towers on seven hilltops.

In late 1947, using combinations of coax and microwave, “Telco” or “Ma Bell” (as engineers referred to it) began building a transcontinental system to accommodate both telephone and television.

By 1948, some geographic areas such as the east (New York, Boston, Philadelphia and Washington), the Midwest (Chicago, Detroit, Milwaukee, Toledo, St. Louis, Buffalo and Cleveland) and the west (Los Angeles and San Francisco) were regionally interconnected.

The first big step toward completing a path west took place when WDTV (now KDKA-TV) in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, went on the air. It was just a transmitter and a film chain as studios for the new station had not yet been built. But it marked the first time two regional networks were linked. With the completion of the eastern feed, live programming from New York could reach the Pittsburgh station from the Philadelphia end of the coaxial cable. Less than a month before the opening, the final connection to the Midwest was completed as Cleveland was connected with Pittsburgh allowing a live television signal from New York to connect with Chicago and the Midwest.

Troy Hill, Pittsburgh, PA – The “Golden Spike” between the East & the Midwest. Courtesy Louis R. DeSanzo

To mark the event, a live show carried on all four networks (ABC, CBS, DuMont & NBC) was broadcast on the evening of January 11, 1949. The 90 minute program consisted of a half hour of speeches by dignitaries followed by 15 minutes of entertainment programming from each network, some originating from New York, some from Chicago. The first half hour also included a ten-minute film “Stepping Along With Television,” prepared by the Bell System just for the event. Though the overall program was titled the “Golden Spike,” the signal at that time could only go as far west as St. Louis.

Microwave work continued across the country as repeaters sprang up on mountains and hilltops, in fields and in cities. From Chicago, the pathway went to Des Moines then to Omaha, Denver, over the Rockies into Salt Lake, across the Sierras and finally into San Francisco. The completion schedule was constantly challenged by the weather. On Mount Rose, Nevada, the site of the highest point of the link, snowdrifts forced workers to use a ski-tow to get up to the site. A total of 107 stations eventually spanned the country.

Testing began as the project neared completion in midsummer 1951. Formal opening of the service wasn’t scheduled until October 1st. But it was the U.S. State Department, not the television networks, who put pressure on the Bell System to flip the switch early.

The route of television’s trancontinental “railroad” in 1951. The east, midwest and west coast were already interconnected with their own regional television networks. The Pittsburgh connection opened the east to the midwest in 1949 followed by the west coast in 1951.

Six years had elapsed since the end of World War II and a peace treaty had yet to be signed by the fifty-one nations who had been at war with Japan. In the end, a peace conference was negotiated that would culminate in the signing of a formal treaty by all combatants. It would be held in San Francisco’s Opera House, the site of the birth of the United Nations, just six years before.

The U.S. Government wanted as much exposure as it could get and they wanted television to play a big part in getting it. But AT&T officials were not anxious to turn on a system that was not ready. Negotiations ensued, the State Department pressed the company to start the service on a temporary basis. AT&T finally gave in agreeing to open the service for this one historic broadcast but put off regular commercial service until one month afterward.

In his book “The Decade That Shaped Television News: CBS in the 1950’s,” Sig Mickelson tells how he came to produce television’s first nationwide mega-event. There was only sufficient bandwidth for one television channel so the networks formed the first television pool coverage. DuMont drew the short straw to handle the pool but admitted it didn’t have the resources to handle the event. It was suggested that KPIX, DuMont’s affiliate in San Francisco, be assigned the event. KPIX was a dual affiliate – DuMont and CBS. So KPIX-TV took the technical responsibility with the resources of CBS producing.

Mickelson explains that as producer of the event for CBS, it was his job to choose the host – later to be referred to as “anchorman.” Mickelson says he had no doubt who he wanted for the job. The articulate, skilled ad libber at the time was delivering the 11pm news on WTOP-TV, the CBS affiliate in Washington, D.C. His name – Walter Cronkite.

So it was that on September 4th, 1951, a live image of President Harry Truman was transmitted across the entire nation. In its September 10th, 1951, issue, Broadcasting magazine reported 94 of the nation’s 107 television stations carried the live broadcasts (most of the remaining stations were off the connection route) making it available to a potential audience of nearly 40 million viewers.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now