This is part 2 of a series on mobile filmmaking, in this case, specifically, mobile journalism (aka MoJo), which started a couple of weeks ago with our look at MoJo journalist Caroline Scott.

There is no shortage of stories of businesses and industries which have been irreversibly affected by the global COVID-19 pandemic. One of the industries hit hardest has been video and film production. Whether it’s major movies and television productions forced to stop, movie theaters which had to close temporarily (or go out of business all together), or corporate video teams which had to switch to an all remote workflow.

Another aspect of this industry that has seen profound changes, has been the journalism and news-gathering business.

Leonor Suárez, a journalist based in Asturias, Spain, is one of many traditional journalists who has recently pivoted to mobile journalism (aka “MoJo”) due to the COVID-19 pandemic. She explains. “When the lockdown started last March here in Europe, we were stuck at home, and overnight we had to start using our phone to report from our home and the street. So, there was a big leap in MoJo since the beginning of the pandemic.”

Suárez works for Asturias’ public television where she runs a weekly news program that produces 35-50 minute long-form stories on current affairs. From time to time, they also run shorter segments related to a larger story which they share on social media.

Her start into mobile journalism

Suárez studied journalism in school, although she admits that university tends to be more focused on theory than practice. However, it wasn’t until 2014 that Suárez discovered mobile journalism. “I discovered MoJo and realized that it was really easy to tell the story, which gave me a lot of opportunities that I didn’t have as a traditional journalist. I have been learning video production on the go. When I started learning mobile journalism, I attended some workshops and learned from the community.”

Before MoJo, Suárez never picked up a video camera or filmed, but instead, focused on scriptwriting. Suddenly, Suárez found herself not only writing the scripts, but also filming, and editing—lots of editing. “With MoJo, I realized I could do all of it myself.”

How else does mobile journalism differ from traditional journalism?

As a traditional journalist, Suárez was used to going out on the scene with a camera crew and a colleague, who would be responsible for filming. “During those days, it was easier to relax and just focus on the questions that I needed to ask for the story. However, this is completely different when I am alone as a mobile journalist and am the one that is both filming and asking questions.”

When arriving at a scene as a mobile journalist, Suárez first takes five minutes to organize everything before starting. “There are lots of things that you have to focus on from the lighting, audio, framing, the questions you need to ask, as well as what is behind the person—so it can be a real challenge.”

While admitting that mobile journalism is no easy feat, Suárez finds it rewarding at the end of the day. “If you can handle all of these things, you will have all of the tools and power in your hands to tell the story.”

Broadcasting in Europe compared to the United States

As a mobile journalist frequently on the go, Suárez chooses to shoot with her iPhone 11 Pro. Just as anywhere else in the world, certain specifications need to be followed to meet broadcast standards. Formatting wise, PAL is used as the standard in Spain. However, smartphones are typically manufactured to film at 30 frames per second whereas PAL is 25. That is where an app like FiLMiC Pro comes in to set the exact frame rate needed.

“Even though I use a smartphone, I still need a certain level of quality in the filming. That’s why I always film with FiLMiC Pro, where I can manually adjust most features and adapt my filming to what my station needs.”

Other settings needed to meet the quality needs for television broadcasting include filming at full HD in 1080p and a shutter speed of 1/50 so as to achieve a 180-degree shutter angle.

Whenever possible, Suárez prefers to shoot in daylight. “However, if I am indoors and don’t have enough light, or if it is dark outside, I use an external LED light that I leave in my MoJo kit.”

The workflow

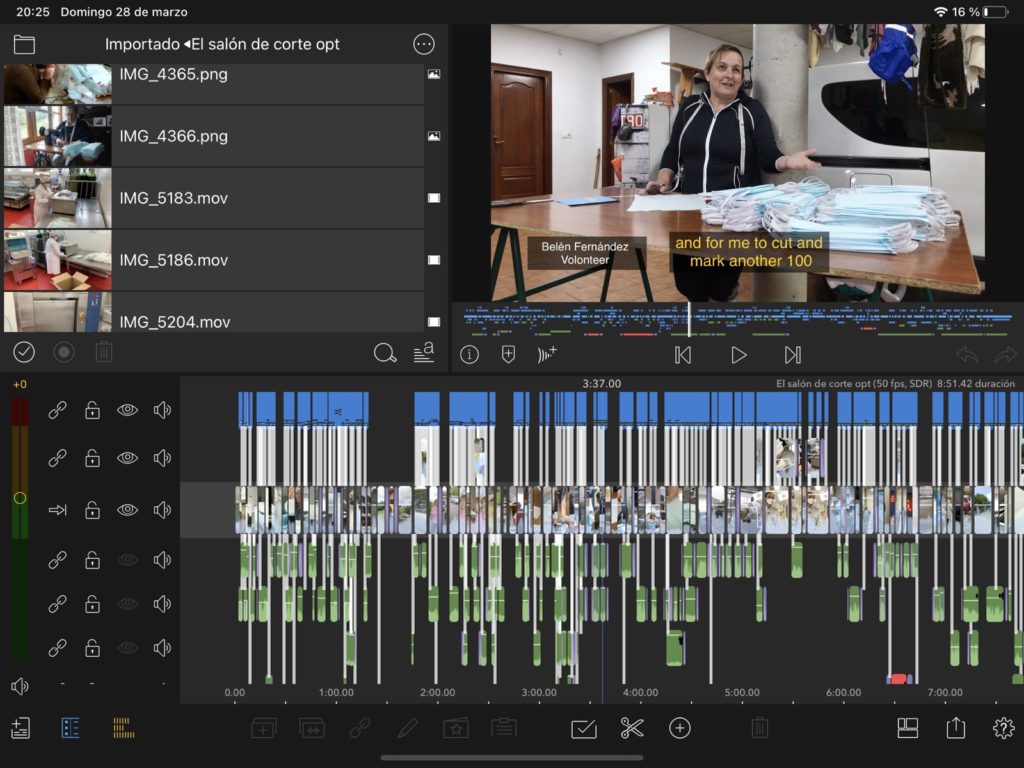

Suárez says the first thing she does in post-production is transfer the files from her phone to her iPad, as she finds it to be easier to edit on the larger screen when adding music and working with many audio tracks. Then, she edits the video in LumaFusion, where she does everything from color grading to key-framing movement.

Post-editing, Suárez typically uploads her finished projects to the cloud to deliver to her station. Occasionally, they also use WeTransfer, Dropbox, or similar services, depending on the file’s size.

MoJo will continue to grow

“For new journalists that are now graduating from university, they are all interested in learning these skills,” Suárez says. “I am seeing a lot of interest in the new generation of journalists.”

According to Suárez, there are also more middle-aged journalists than ever who never before considered filming with their smartphone. However, since the pandemic, they had to adapt to the circumstances in which they were living.

About the co-author: For this piece, Leonor was interviewed by Ron Dawson, and it was co-written by Hailey Lucas and Ron Dawson.

Hailey is a professional content marketer and a senior writer on the Blade Ronner Media writing team. She is passionate about all things marketing, tech, and social impact. In her free time, she blogs about her digital nomad lifestyle while slowly traveling around the world. Hailey’s work has been featured in various marketing and tech publications receiving over 500K – 1M monthly views.

Filmtools

Filmmakers go-to destination for pre-production, production & post production equipment!

Shop Now